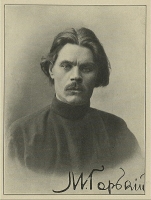

阅读高尔基 Maksim Gorky在小说之家的作品!!! | |||||||

童年和青少年

高尔基出生于一个贫苦的家庭,他的祖父是伏尔加河上的纤夫,他的父亲是一个木匠而且很早就去世了。他来到外祖父家里生活,外祖父是一个凶悍的人,并且他的两个舅舅为争夺家产闹得不可开交。这个时代在俄罗斯社会不平等正在成为文学的一个重要题材和社会冲突的原因。具体情况可在《童年》中找到。

从他十岁开始高尔基就得自己赚钱为生,一开始拾垃圾。他青少年时期做过许多不同的活:信使、厨房里的杂工、卖鸟、售货员、画圣像、船上的杂工、面包店的学徒、工地上的杂工、晚间的看守人、铁路职工和在律师事务所中做杂工。参见《在人间》。 18世纪80年代后期他来到喀山并被成功地被那里的大学接受为大学生。在这里他接触到了运动。他在一个面包坊工作,这个面包坊同时也是一个秘密马克思主义小组的图书馆。他很好学,读了许多书,靠自学的方式获得了许多,但不系统的知识。他与他的同学之间的差别很大,因此他几乎没有朋友。这有可能是1887年一次未成功的自杀企图的原因。在这个过程中他的肺被损坏,从此他一直患肺结核。在《我的大学》中提到。

作家和活动家

由于他与组织的接触从1889年开始沙皇开始注意到他。同年他将他的一首诗寄给一个诗人,但却受到了毁灭性的批评。此后一段时间里他放弃了文学创作。他徒步跋涉穿越俄罗斯、乌克兰,翻越高加索山脉一直到第比利斯。在那里他接触到其他者和大学生。这些人鼓励他将他的经历写下来。1892年9月12日他的第一部小说在当地的一份报纸上被发表。他使用了马克西姆-高尔基(苦人)作为笔名。

此后他去萨马拉并在那里的一份地方报纸获得了一个记者的工作。1894年他发表的一部小说正式奠定了他的作家地位。1898年发表的小说集也很受欢迎。1901年圣彼得堡的一次学生示威被血腥后他写了《海燕之歌》,这首诗经常在聚会上被朗诵。

他的话剧《小市民》(1901年)和《底层》(1902年)被发表后他如此有名,以至于所有当局他的企图都遭到强烈的反对。由于他签署了一份反对官方对那次学生事件的报道的文章他被流放到克里米亚,在那里他受到了他的朋友和敬仰者的隆重欢迎。当沙皇尼古拉二世将他接收为俄罗斯科学院名誉院士的决定否决时,许多知名的院士对此提出,包括安东-契诃夫。1905年1月9日沙皇再次血腥毫无武装的平民示威后,高尔基对此提出。为此他被关押。外国传媒对此事表示极为气愤,这一举动迫使沙皇政府释放高尔基。

十月前

1905年二月后俄罗斯的气氛稍有开放,高尔基在这段时间里不断地写文章和参加集会宣传。通过他参加创办的《新生命》杂志他认识了列宁,列宁在该杂志做总编辑。

但此后压迫又加强后他便出国了。在法国他反对西方国家向在日俄战争中被削弱的贷款。当西方国家决定向贷款后他写了一篇侮辱性的小文章《美丽的法国》。在美国他企图为捐款,但他的敌人使用他与他的女随行者并未结婚来诽谤他,因此这次捐款几乎毫无效果。

他写了《母亲》,列宁给了这部小说很高的评价,后来这部小说在苏联成为一部经典著作。

在他反对上述贷款后他无法再回到。从1907年到1913年他在意大利卡普里岛上渡过。这段时间里他几乎只为俄罗斯工作。他和列宁一起成立了一个培养家和宣传员的学校,接见了许多特地来拜访他的人。他收到许多来自俄罗斯各地的信,在这些信中许多人将他们的希望和忧愁讲给他听,他也回复了许多信。

在这段时间里他和列宁发生了第一次冲突。对高尔基来说宗教是非常重要的。列宁将此看做是"偏离了马克思主义"。这次冲突的直接原因是高尔基的一篇小文《忏悔》,在这篇文章中他试图将教与马克思主义结合起来。1913年这个冲突再次爆发。

1913年就罗曼诺夫王朝掌权300周年的特赦给予高尔基重返俄罗斯的机会。

高尔基对1917年的十月的悲观看法是他与列宁发生第二次大冲突的原因。高尔基从原则上同意社会,但他认为俄罗斯民族还不成熟,大众还需要形成必要的知觉才能从他们的不幸中起义。后来他说他当时"害怕无产阶级会瓦解我们所拥有的唯一的力量:布尔什维克的、获得培养的工人。这个瓦解会长时间地破坏社会本身......"。

反对派和

后高尔基立刻组织了一系列协会来防止他所担心的科学和文化的没落。"提高学者生活水平委员会"的目的是保护特别受到饥饿、寒冷和无常威胁的知识分子而成立的。他组织了一份报纸来反对列宁的《真理报》和反对"私刑"和"权力的毒药"。1918年这份杂志被禁止。高尔基与列宁之间的分歧是如此之大以至于列宁劝告高尔基到外国疗养院去治疗他的肺结核。

从1921年到1924年他在柏林渡过。他不信任列宁的继承人,因此在列宁死后也没有回到。他打算重返意大利,意大利的法西斯政府在经过一段犹豫后同意他去索伦托。他在那里一直待到1927年,在那里他写了《回忆列宁》,在这部文章中他将列宁称为他最爱戴的人。此外他还在写两部他的长篇小说。

苏联模范作家

1927年10月22日苏联科学院决定就高尔基开始写作35周年授予他无产阶级作家的称号。当他此后不久回到苏联后他受到了许多荣誉:他被授予列宁勋章,成为苏联中央委员会成员。苏联全国庆祝他的60岁生日,许多单位以他命名。他的诞生地被改名为高尔基市。

许多他的适合于社会主义现实派的作品被宣扬,其它作品却默而不言。尤其是《母亲》(这是高尔基唯一一部主人公是一个无产阶级工人的作品)成为苏联文学的榜范。

在高尔基最后的这段时间里他称他过去对的悲观主义是错误的,他成为斯大林的模范作家。他周游苏联,对最近几年来取得的进步表示吃惊,这些进步的阴暗面他似乎没有注意到。大多数时间里他住在莫斯科附近的一座洋房中并被受到克格勃间谍的时时刻刻的监视。他依然试图对大众进行启蒙教育和提拔年轻的作家。

1936年6月18日高尔基因肺炎逝世。他被斯大林害死或死于托洛茨基主义者的阴谋的传说未被证实。

From 1906 to 1913 and from 1921 to 1929 he lived abroad, mostly in Capri, Italy; after his return to the Soviet Union he accepted the cultural policies of the time, although he was not permitted to leave the country.Serge,Memoirs,268,Ivanov,"Pochemu",101-2,127-8,131.

Gorky was born in Nizhny Novgorod and became an orphan at the age of ten. In 1880, at the age of twelve, he ran away from home in an effort to find his grandmother. Gorky was brought up by his grandmother, an excellent storyteller. Her death deeply affected him, and after an attempt at suicide in December 1887, he travelled on foot across the Russian Empire for five years, changing jobs and accumulating impressions used later in his writing.

As a journalist working in provincial newspapers, he wrote under the pseudonym Иегудиил Хламида (Jehudiel Khlamida— suggestive of "cloak-and-dagger" by the similarity to the Greek chlamys, "cloak"). He began using the pseudonym Gorky (literally "bitter") in 1892, while working in Tiflis newspaper Кавказ (The Caucasus). The name reflected his simmering anger about life in Russia and a determination to speak the bitter truth. Gorky's first book Очерки и рассказы (Essays and Stories) in 1898 enjoyed a sensational success and his career as a writer began. Gorky wrote incessantly, viewing literature less as an aesthetic practice (though he worked hard on style and form) than as a moral and political act that could change the world. He described the lives of people in the lowest strata and on the margins of society, revealing their hardships, humiliations, and brutalization, but also their inward spark of humanity.

Gorky’s reputation as a unique literary voice from the bottom strata of society and as a fervent advocate of Russia's social, political, and cultural transformation (by 1899, he was openly associating with the emerging Marxist social-democratic movement) helped make him a celebrity among both the intelligentsia and the growing numbers of "conscious" workers. At the heart of all his work was a belief in the inherent worth and potential of the human person (личность, lichnost'). He counterposed vital individuals, aware of their natural dignity, and inspired by energy and will, to people who succumb to the degrading conditions of life around them. Still, both his writings and his letters reveal a "restless man" (a frequent self-description) struggling to resolve contradictory feelings of faith and skepticism, love of life and disgust at the vulgarity and pettiness of the human world.

He publicly opposed the Tsarist regime and was arrested many times. Gorky befriended many revolutionaries and became Lenin's personal friend after they met in 1902. He exposed governmental control of the press (see Matvei Golovinski affair). In 1902, Gorky was elected an honorary Academician of Literature, but Nicholas II ordered this annulled. In protest, Anton Chekhov and Vladimir Korolenko left the Academy.

The years 1900 to 1905 saw a growing optimism in Gorky’s writings. He became more involved in the opposition movement, for which he was again briefly imprisoned in 1901. In 1904, having severed his relationship with the Moscow Art Theatre in the wake of conflict with Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, Gorky returned to Nizhny Novgorod to establish a theatre of his own. Both Constantin Stanislavski and Savva Morozov provided financial support for the venture. Stanislavski saw in Gorky's theatre an opportunity to develop the network of provincial theatres that he hoped would reform the art of the stage in Russia, of which he had dreamed since the 1890s. He sent some pupils from the Art Theatre School—as well as Ioasaf Tikhomirov, who ran the school—to work there. By the autumn, however, after the censor had banned every play that the theatre proposed to stage, Gorky abandoned the project. Now a financially-successful author, editor, and playwright, Gorky gave financial support to the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), though he also supported liberal appeals to the government for civil rights and social reform. The brutal shooting of workers marching to the Tsar with a petition for reform on January 9, 1905 (known as the "Bloody Sunday"), which set in motion the Revolution of 1905, seems to have pushed Gorky more decisively toward radical solutions. He now became closely associated with Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik wing of the party—though it is not clear whether he ever formally joined and his relations with Lenin and the Bolsheviks would always be rocky. His most influential writings in these years were a series of political plays, most famously The Lower Depths (1902). In 1906, the Bolsheviks sent him on a fund-raising trip to the United States, where in the Adirondack Mountains Gorky wrote his famous novel of revolutionary conversion and struggle, Мать (Mat’, The Mother). His experiences there—which included a scandal over his traveling with his lover rather than his wife—deepened his contempt for the "bourgeois soul" but also his admiration for the boldness of the American spirit. While briefly imprisoned in Peter and Paul Fortress during the abortive 1905 Russian Revolution, Gorky wrote the play Children of the Sun, nominally set during an 1862 cholera epidemic, but universally understood to relate to present-day events.

From 1906 to 1913, Gorky lived on the island of Capri, partly for health reasons and partly to escape the increasingly repressive atmosphere in Russia. He continued to support the work of Russian social-democracy, especially the Bolsheviks, and to write fiction and cultural essays. Most controversially, he articulated, along with a few other maverick Bolsheviks, a philosophy he called "God-Building", which sought to recapture the power of myth for the revolution and to create a religious atheism that placed collective humanity where God had been and was imbued with passion, wonderment, moral certainty, and the promise of deliverance from evil, suffering, and even death. Though 'God-Building' was suppressed by Lenin, Gorky retained his belief that "culture"—the moral and spiritual awareness of the value and potential of the human self—would be more critical to the revolution’s success than political or economic arrangements.

An amnesty granted for the 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty allowed Gorky to return to Russia in 1913, where he continued his social criticism, mentored other writers from the common people, and wrote a series of important cultural memoirs, including the first part of his autobiography. On returning to Russia, he wrote that his main impression was that "everyone is so crushed and devoid of God's image." The only solution, he repeatedly declared, was "culture".

During World War I, his apartment in Petrograd was turned into a Bolshevik staff room, but his relations with the Communists turned sour. After his newspaper Novaya Zhizn (Новая Жизнь, "New Life") fell prey to Bolshevik censorship, Gorky published a collection of essays critical of the Bolsheviks called Untimely Thoughts in 1918. (It would not be published in Russia again until the end of the Soviet Union.) The essays call Lenin a tyrant for his senseless arrests and repression of free discourse, and an anarchist for his conspiratorial tactics; Gorky compares Lenin to both the Tsar and Nechayev.

In August 1921, Nikolai Gumilyov, his friend, fellow writer and Anna Akhmatova's husband, was arrested by the Petrograd Cheka for his monarchist views. Gorky hurried to Moscow, obtained an order to release Gumilyov from Lenin personally, but upon his return to Petrograd he found out that Gumilyov had already been shot. In October, Gorky returned to Italy on health grounds: he had tuberculosis.

According to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Gorky's return to the Soviet Union was motivated by material needs. In Sorrento, Gorky found himself without money and without fame. He visited the USSR several times after 1929, and in 1932 Joseph Stalin personally invited him to return for good, an offer he accepted. In June 1929, Gorky visited Solovki (cleaned up for this occasion) and wrote a positive article about that Gulag camp, which had already gained ill fame in the West. Later he stated that everything he had written was under the control of censors. What he actually saw and thought when visiting the camp has been a highly discussed topic.

Gorky's return from Fascist Italy was a major propaganda victory for the Soviets. He was decorated with the Order of Lenin and given a mansion (formerly belonging to the millionaire Ryabushinsky, now the Gorky Museum) in Moscow and a dacha in the suburbs. One of the central Moscow streets, Tverskaya, was renamed in his honor, as was the city of his birth. The largest fixed-wing aircraft in the world in the mid-1930s, the Tupolev ANT-20 (photo), was also named Maxim Gorky. It was used for propaganda purposes and often demonstratively flew over the Soviet capital.

On October 11, 1931 Gorky read his fairy tale "A Girl and Death" to his visitors Joseph Stalin, Kliment Voroshilov and Vyacheslav Molotov, an event that was later depicted by Viktor Govorov on his painting. On that same day Stalin left his autograph on the last page of this work by Gorky:

Эта штука сильнее чем "Фауст" Гёте (любовь побеждает смерть) English: "This piece is stronger than Goethe's Faust (love defeats death)".

In 1933 Gorky edited an infamous book about the White Sea-Baltic Canal, presented as an example of "successful rehabilitation of the former enemies of proletariat".

With the increase of Stalinist repression and especially after the assassination of Sergei Kirov in December 1934, Gorky was placed under unannounced house arrest in his Moscow house.

The sudden death of his son Maxim Peshkov in May 1934 was followed by the death of Maxim Gorky himself in June 1936. Speculation has long surrounded the circumstances of his death. Stalin and Molotov were among those who carried Gorky's coffin during the funeral.

During the Bukharin show trials in 1938, one of the charges was that Gorky was killed by Yagoda's NKVD agents.

In Soviet times, before and after his death, the complexities in Gorky's life and outlook were reduced to an iconic image (echoed in heroic pictures and statues dotting the countryside): Gorky as a great Russian writer who emerged from the common people, a loyal friend of the Bolsheviks, and the founder of the increasingly canonical "socialist realism". In turn, dissident intellectuals dismissed Gorky as a tendentious ideological writer[citation needed], though some Western writers[who?] noted Gorky's doubts and criticisms[citation needed]. Today, greater balance is to be found in works on Gorky, where we see a growing appreciation of the complex moral perspective on modern Russian life expressed in his writings [citation needed]. Some historians [who?] have begun to view Gorky as one of the most insightful observers of both the promises and moral dangers of revolution in Russia.

Selected works

Makar Chudra (Макар Чудра), short story, 1892

Chelkash (Челкаш), 1895

Malva, 1897

Creatures That Once Were Men, stories in English translation (1905)

This contained an introduction by G. K. Chesterton

Twenty-six Men and a Girl

Foma Gordeyev (Фома Гордеев), novel, 1899

Three of Them (Трое), 1900

The Song of the Stormy Petrel (Песня о Буревестнике), 1901

Song of a Falcon (Песня о Соколе),short story, 1902

The Life of Matvei Kozhemyakin (Жизнь Матвея Кожемякина)

The Mother (Мать), novel, 1907

A Confession (Исповедь), 1908

Okurov City (Городок Окуров), novel, 1908

My Childhood (Детство), 1913–1914

In the World (В людях), 1916

Chaliapin, articles in Letopis, 1917

Commemorative coin, released in the USSR on his 120th anniv. features his portrait and a stormy petrel over the storm seaUntimely Thoughts, articles, 1918

My Universities (Мои университеты), 1923

The Artamonov Business (Дело Артамоновых), 1927

Life of Klim Samgin (Жизнь Клима Самгина), epopeia, 1927–36

Reminiscences of Tolstoy (1919), Chekhov (1905–21), and Andreyev

V.I.Lenin (В.И.Ленин), reminiscence, 1924–31

The I.V. Stalin White Sea - Baltic Sea Canal, 1934 (editor-in-chief)

Drama

The Philistines (Мещане), 1901

The Lower Depths (На дне), 1902

Summerfolk (Дачники), 1904

Children of the Sun (Дети солнца), 1905

Barbarians, 1905

Enemies, 1906

Queer People, 1910

Vassa Zheleznova, 1910

The Zykovs, 1913

Counterfeit Money, 1913

Yegor Bulychov and Others, 1932

Dostigayev and Others, 1933

Adaptations

The German modernist theatre practitioner Bertolt Brecht based his epic play The Mother (1932) on Gorky's novel of the same name. Gorky's novel was also adapted for an opera by Valery Zhelobinsky in 1938. In 1912, the Italian composer Giacomo Orefice based his opera Radda on the character of Radda from Makar Chudra.

Works about Gorky

The Gorky Trilogy is a series of three feature films—The Childhood of Maxim Gorky, My Apprenticeship, and My Universities—directed by Mark Donskoi, filmed in the Soviet Union, released 1938-1940. The trilogy was adapted from Gorky's autobiography.

The Murder of Maxim Gorky. A Secret Execution by Arkady Vaksberg. (Enigma Books: New York, 2007. ISBN 978-1-929631-62-9.)

Quotations

"One has to be able to count if only so that at fifty one doesn't marry a girl of twenty"

"Если враг не сдается, его уничтожают" (If the enemy doesn't surrender, he shall be exterminated!)

"When work is a pleasure, life is a joy! When work is duty, life is slavery."

"One miserable being seeks another miserable being; then he's happy."

"Politics is the seedbed of social enmity, evil suspicions, shameless lies, morbid ambitions, and disrespect for the individual. Name anything bad in man, and it is precisely in the soil of political struggle that it grows with abundance."