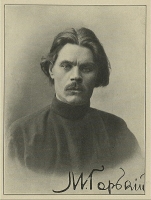

yuèdòugāo 'ěr jī Maksim Gorkyzài小说之家dezuòpǐn!!! | |||||||

tóng nián hé qīng shàonián

gāo 'ěr jī chū shēng yú yī gè pín kǔ de jiā tíng, tā de zǔ fù shì fú 'ěr jiā hé shàng de qiànfū, tā de fù qīn shì yī gè mù jiàng 'ér qiě hěn zǎo jiù qù shì liǎo。 tā lái dào wài zǔ fù jiā lǐ shēng huó, wài zǔ fù shì yī gè xiōng hàn de rén, bìng qiě tā de liǎng gè jiù jiù wéi zhēng duó jiā chǎn nào dé bù kě kāi jiāo。 zhè gè shí dài zài 'é luó sī shè huì bù píng děng zhèng zài chéng wéi wén xué de yī gè zhòng yào tí cái hé shè huì chōng tū de yuán yīn。 jù tǐ qíng kuàng kě zài《 tóng nián》 zhōng zhǎo dào。

cóng tā shí suì kāi shǐ gāo 'ěr jī jiù dé zì jǐ zuàn qián wéi shēng, yī kāi shǐ shí lā jī。 tā qīng shàonián shí qī zuò guò xǔ duō bù tóng de huó: xìn shǐ、 chú fáng lǐ de zá gōng、 mài niǎo、 shòu huò yuán、 huà shèng xiàng、 chuán shàng de zá gōng、 miàn bāo diàn de xué tú、 gōng dì shàng de zá gōng、 wǎn jiān de kānshǒu rén、 tiě lù zhí gōng hé zài lǜ shī shì wù suǒ zhōng zuò zá gōng。 cān jiàn《 zài rén jiān》。 18 shì jì 80 nián dài hòu qī tā lái dào kā shān bìng bèi chéng gōng dì bèi nà lǐ de dà xué jiē shòu wéi dà xué shēng。 zài zhè lǐ tā jiē chù dào liǎo yùn dòng。 tā zài yī gè miàn bāo fāng gōng zuò, zhè gè miàn bāo fāng tóng shí yě shì yī gè mì mì mǎ kè sī zhù yì xiǎo zǔ de tú shū guǎn。 tā hěn hàoxué, dú liǎo xǔ duō shū, kào zì xué de fāng shì huò dé liǎo xǔ duō, dàn bù xì tǒng de zhī shí。 tā yǔ tā de tóng xué zhī jiān de chā bié hěn dà, yīn cǐ tā jīhū méi yòu péng yǒu。 zhè yòu kě néng shì 1887 nián yī cì wèi chéng gōng de zì shā qǐ tú de yuán yīn。 zài zhè gè guò chéng zhōng tā de fèi bèi sǔn huài, cóng cǐ tā yī zhí huàn fèi jié hé。 zài《 wǒ de dà xué》 zhōng tí dào。

zuò jiā hé huó dòng jiā

yóu yú tā yǔ zǔ zhì de jiē chù cóng 1889 nián kāi shǐ shā huáng kāi shǐ zhù yì dào tā。 tóng nián tā jiāng tā de yī shǒu shī jì gěi yī gè shī rén, dàn què shòu dào liǎo huǐ miè xìng de pī píng。 cǐ hòu yī duàn shí jiān lǐ tā fàng qì liǎo wén xué chuàng zuò。 tā tú bù bá shè chuān yuè 'é luó sī、 wū kè lán, fān yuè gāo jiā suǒ shān mài yī zhí dào dì bǐ lì sī。 zài nà lǐ tā jiē chù dào qí tā zhě hé dà xué shēng。 zhè xiē rén gǔ lì tā jiāng tā de jīng lì xiě xià lái。 1892 nián 9 yuè 12 rì tā de dì yī bù xiǎo shuō zài dāng dì de yī fèn bào zhǐ shàng bèi fā biǎo。 tā shǐ yòng liǎo mǎ kè xī mǔ - gāo 'ěr jī( kǔ rén) zuò wéi bǐ míng。

cǐ hòu tā qù sà mǎ lā bìng zài nà lǐ de yī fèn dì fāng bào zhǐ huò dé liǎo yī gè jì zhě de gōng zuò。 1894 nián tā fā biǎo de yī bù xiǎo shuō zhèng shì diàn dìng liǎo tā de zuò jiā dì wèi。 1898 nián fā biǎo de xiǎo shuō jí yě hěn shòu huān yíng。 1901 nián shèng bǐ dé bǎo de yī cì xué shēng shì wēi bèi xuè xīng hòu tā xiě liǎo《 hǎi yàn zhī gē》, zhè shǒu shī jīng cháng zài jù huì shàng bèi lǎng sòng。

tā de huà jù《 xiǎo shì mín》( 1901 nián) hé《 dǐ céng》( 1902 nián) bèi fā biǎo hòu tā rú cǐ yòu míng, yǐ zhì yú suǒ yòu dāng jú tā de qǐ tú dū zāo dào qiáng liè de fǎn duì。 yóu yú tā qiān shǔ liǎo yī fèn fǎn duì guān fāng duì nà cì xué shēng shì jiàn de bào dào de wén zhāng tā bèi liú fàng dào kè lǐ mǐ yà, zài nà lǐ tā shòu dào liǎo tā de péng yǒu hé jìng yǎng zhě de lóng zhòng huān yíng。 dāng shā huáng ní gǔ lā 'èr shì jiāng tā jiē shōu wéi 'é luó sī kē xué yuàn míng yù yuàn shì de jué dìng fǒu jué shí, xǔ duō zhī míng de yuàn shì duì cǐ tí chū, bāo kuò 'ān dōng - qì hē fū。 1905 nián 1 yuè 9 rì shā huáng zài cì xuè xīng háo wú wǔ zhuāng de píng mín shì wēi hòu, gāo 'ěr jī duì cǐ tí chū。 wèicǐ tā bèi guān yā。 wài guó chuán méi duì cǐ shì biǎo shì jí wéi qì fèn, zhè yī jǔ dòng pò shǐ shā huáng zhèng fǔ shì fàng gāo 'ěr jī。

shí yuè qián

1905 nián 'èr yuè hòu 'é luó sī de qì fēn shāo yòu kāi fàng, gāo 'ěr jī zài zhè duàn shí jiān lǐ bù duàn dì xiě wén zhāng hé cān jiā jí huì xuān chuán。 tōng guò tā cān jiā chuàng bàn de《 xīn shēng mìng》 zá zhì tā rèn shí liǎo liè níng, liè níng zài gāi zá zhì zuò zǒng biān ji。

dàn cǐ hòu yā pò yòu jiā qiáng hòu tā biàn chū guó liǎo。 zài fǎ guó tā fǎn duì xī fāng guó jiā xiàng zài rì 'é zhàn zhēng zhōng bèi xuē ruò de dài kuǎn。 dāng xī fāng guó jiā jué dìng xiàng dài kuǎn hòu tā xiě liǎo yī piān wǔ rǔ xìng de xiǎo wén zhāng《 měi lì de fǎ guó》。 zài měi guó tā qǐ tú wéi juān kuǎn, dàn tā de dí rén shǐ yòng tā yǔ tā de nǚ suí xíng zhě bìng wèi jié hūn lái fěi bàng tā, yīn cǐ zhè cì juān kuǎn jīhū háo wú xiào guǒ。

tā xiě liǎo《 mǔ qīn》, liè níng gěi liǎo zhè bù xiǎo shuō hěn gāo de píng jià, hòu lái zhè bù xiǎo shuō zài sū lián chéng wéi yī bù jīng diǎn zhù zuò。

zài tā fǎn duì shàng shù dài kuǎn hòu tā wú fǎ zài huí dào。 cóng 1907 nián dào 1913 nián tā zài yì dà lì kǎ pǔ lǐ dǎo shàng dù guò。 zhè duàn shí jiān lǐ tā jīhū zhǐ wéi 'é luó sī gōng zuò。 tā hé liè níng yī qǐ chéng lì liǎo yī gè péi yǎng jiā hé xuān chuán yuán de xué xiào, jiē jiàn liǎo xǔ duō tè dì lái bài fǎng tā de rén。 tā shōu dào xǔ duō lái zì 'é luó sī gè dì de xìn, zài zhè xiē xìn zhōng xǔ duō rén jiāng tā men de xī wàng hé yōu chóu jiǎng gěi tā tīng, tā yě huí fù liǎo xǔ duō xìn。

zài zhè duàn shí jiān lǐ tā hé liè níng fā shēng liǎo dì yī cì chōng tū。 duì gāo 'ěr jī lái shuō zōng jiào shì fēi cháng zhòng yào de。 liè níng jiāng cǐ kàn zuò shì " piān lí liǎo mǎ kè sī zhù yì "。 zhè cì chōng tū de zhí jiē yuán yīn shì gāo 'ěr jī de yī piān xiǎo wén《 chàn huǐ》, zài zhè piān wén zhāng zhōng tā shì tú jiāng jiào yǔ mǎ kè sī zhù yì jié hé qǐ lái。 1913 nián zhè gè chōng tū zài cì bào fā。

1913 nián jiù luó màn nuò fū wáng cháo zhǎng quán 300 zhōu nián de tè shè jǐyǔ gāo 'ěr jī chóngfǎn 'é luó sī de jī huì。

gāo 'ěr jī duì 1917 nián de shí yuè de bēi guān kàn fǎ shì tā yǔ liè níng fā shēng dì 'èr cì dà chōng tū de yuán yīn。 gāo 'ěr jī cóng yuán zé shàng tóng yì shè huì, dàn tā rèn wéi 'é luó sī mín zú hái bù chéng shú, dà zhòng hái xū yào xíng chéng bì yào de zhī jué cái néng cóng tā men de bù xìng zhōng qǐ yì。 hòu lái tā shuō tā dāng shí " hài pà wú chǎn jiē jí huì wǎ jiě wǒ men suǒ yōng yòu de wéi yī de lì liàng: bù 'ěr shí wéi kè de、 huò dé péi yǎng de gōng rén。 zhè gè wǎ jiě huì cháng shí jiān dì pò huài shè huì běn shēn ......"。

fǎn duì pài hé

hòu gāo 'ěr jī lì kè zǔ zhì liǎo yī xì liè xié huì lái fáng zhǐ tā suǒ dān xīn de kē xué hé wén huà de mòluò。 " tí gāo xué zhě shēng huó shuǐ píng wěi yuán huì " de mù de shì bǎo hù tè bié shòu dào jī 'è、 hán lěng hé wú cháng wēi xié de zhī shí fènzǐ 'ér chéng lì de。 tā zǔ zhì liǎo yī fèn bào zhǐ lái fǎn duì liè níng de《 zhēn lǐ bào》 hé fǎn duì " sī xíng " hé " quán lì de dú yào "。 1918 nián zhè fèn zá zhì bèi jìn zhǐ。 gāo 'ěr jī yǔ liè níng zhī jiān de fēn qí shì rú cǐ zhī dà yǐ zhì yú liè níng quàn gào gāo 'ěr jī dào wài guó liáo yǎng yuàn qù zhì liáo tā de fèi jié hé。

cóng 1921 nián dào 1924 nián tā zài bólín dù guò。 tā bù xìn rèn liè níng de jì chéng rén, yīn cǐ zài liè nìngsǐ hòu yě méi yòu huí dào。 tā dǎ suàn chóngfǎn yì dà lì, yì dà lì de fǎ xī sī zhèng fǔ zài jīng guò yī duàn yóu yù hòu tóng yì tā qù suǒ lún tuō。 tā zài nà lǐ yī zhí dài dào 1927 nián, zài nà lǐ tā xiě liǎo《 huí yì liè níng》, zài zhè bù wén zhāng zhōng tā jiāng liè níng chēng wéi tā zuì 'ài dài de rén。 cǐ wài tā hái zài xiě liǎng bù tā de cháng piān xiǎo shuō。

sū lián mó fàn zuò jiā

1927 nián 10 yuè 22 rì sū lián kē xué yuàn jué dìng jiù gāo 'ěr jī kāi shǐ xiě zuò 35 zhōu nián shòu yú tā wú chǎn jiē jí zuò jiā de chēng hào。 dāng tā cǐ hòu bù jiǔ huí dào sū lián hòu tā shòu dào liǎo xǔ duō róng yù: tā bèi shòu yú liè níng xūn zhāng, chéng wéi sū lián zhōng yāng wěi yuán huì chéng yuán。 sū lián quán guó qìng zhù tā de 60 suì shēng rì, xǔ duō dān wèi yǐ tā mìng míng。 tā de dàn shēng dì bèi gǎi míng wéi gāo 'ěr jī shì。

xǔ duō tā de shì hé yú shè huì zhù yì xiàn shí pài de zuò pǐn bèi xuān yáng, qí tā zuò pǐn què mò 'ér bù yán。 yóu qí shì《 mǔ qīn》( zhè shì gāo 'ěr jī wéi yī yī bù zhù rén gōng shì yī gè wú chǎn jiē jí gōng rén de zuò pǐn) chéng wéi sū lián wén xué de bǎng fàn。

zài gāo 'ěr jī zuì hòu de zhè duàn shí jiān lǐ tā chēng tā guò qù duì de bēi guān zhù yì shì cuò wù de, tā chéng wéi sī dà lín de mó fàn zuò jiā。 tā zhōu yóu sū lián, duì zuì jìn jǐ nián lái qǔ dé de jìn bù biǎo shì chī jīng, zhè xiē jìn bù de yīn 'àn miàn tā sì hū méi yòu zhù yì dào。 dà duō shù shí jiān lǐ tā zhù zài mò sī kē fù jìn de yī zuò yáng fáng zhōng bìng bèi shòu dào kè gé bó jiàndié de shí shí kè kè de jiān shì。 tā yǐ rán shì tú duì dà zhòng jìn xíng qǐ méng jiào yù hé tí bá nián qīng de zuò jiā。

1936 nián 6 yuè 18 rì gāo 'ěr jī yīn fèi yán shì shì。 tā bèi sī dà lín hài sǐ huò sǐ yú tuō luò cí jī zhù yì zhě de yīn móu de chuán shuō wèi bèi zhèng shí。

From 1906 to 1913 and from 1921 to 1929 he lived abroad, mostly in Capri, Italy; after his return to the Soviet Union he accepted the cultural policies of the time, although he was not permitted to leave the country.Serge,Memoirs,268,Ivanov,"Pochemu",101-2,127-8,131.

Gorky was born in Nizhny Novgorod and became an orphan at the age of ten. In 1880, at the age of twelve, he ran away from home in an effort to find his grandmother. Gorky was brought up by his grandmother, an excellent storyteller. Her death deeply affected him, and after an attempt at suicide in December 1887, he travelled on foot across the Russian Empire for five years, changing jobs and accumulating impressions used later in his writing.

As a journalist working in provincial newspapers, he wrote under the pseudonym Иегудиил Хламида (Jehudiel Khlamida— suggestive of "cloak-and-dagger" by the similarity to the Greek chlamys, "cloak"). He began using the pseudonym Gorky (literally "bitter") in 1892, while working in Tiflis newspaper Кавказ (The Caucasus). The name reflected his simmering anger about life in Russia and a determination to speak the bitter truth. Gorky's first book Очерки и рассказы (Essays and Stories) in 1898 enjoyed a sensational success and his career as a writer began. Gorky wrote incessantly, viewing literature less as an aesthetic practice (though he worked hard on style and form) than as a moral and political act that could change the world. He described the lives of people in the lowest strata and on the margins of society, revealing their hardships, humiliations, and brutalization, but also their inward spark of humanity.

Gorky’s reputation as a unique literary voice from the bottom strata of society and as a fervent advocate of Russia's social, political, and cultural transformation (by 1899, he was openly associating with the emerging Marxist social-democratic movement) helped make him a celebrity among both the intelligentsia and the growing numbers of "conscious" workers. At the heart of all his work was a belief in the inherent worth and potential of the human person (личность, lichnost'). He counterposed vital individuals, aware of their natural dignity, and inspired by energy and will, to people who succumb to the degrading conditions of life around them. Still, both his writings and his letters reveal a "restless man" (a frequent self-description) struggling to resolve contradictory feelings of faith and skepticism, love of life and disgust at the vulgarity and pettiness of the human world.

He publicly opposed the Tsarist regime and was arrested many times. Gorky befriended many revolutionaries and became Lenin's personal friend after they met in 1902. He exposed governmental control of the press (see Matvei Golovinski affair). In 1902, Gorky was elected an honorary Academician of Literature, but Nicholas II ordered this annulled. In protest, Anton Chekhov and Vladimir Korolenko left the Academy.

The years 1900 to 1905 saw a growing optimism in Gorky’s writings. He became more involved in the opposition movement, for which he was again briefly imprisoned in 1901. In 1904, having severed his relationship with the Moscow Art Theatre in the wake of conflict with Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, Gorky returned to Nizhny Novgorod to establish a theatre of his own. Both Constantin Stanislavski and Savva Morozov provided financial support for the venture. Stanislavski saw in Gorky's theatre an opportunity to develop the network of provincial theatres that he hoped would reform the art of the stage in Russia, of which he had dreamed since the 1890s. He sent some pupils from the Art Theatre School—as well as Ioasaf Tikhomirov, who ran the school—to work there. By the autumn, however, after the censor had banned every play that the theatre proposed to stage, Gorky abandoned the project. Now a financially-successful author, editor, and playwright, Gorky gave financial support to the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), though he also supported liberal appeals to the government for civil rights and social reform. The brutal shooting of workers marching to the Tsar with a petition for reform on January 9, 1905 (known as the "Bloody Sunday"), which set in motion the Revolution of 1905, seems to have pushed Gorky more decisively toward radical solutions. He now became closely associated with Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik wing of the party—though it is not clear whether he ever formally joined and his relations with Lenin and the Bolsheviks would always be rocky. His most influential writings in these years were a series of political plays, most famously The Lower Depths (1902). In 1906, the Bolsheviks sent him on a fund-raising trip to the United States, where in the Adirondack Mountains Gorky wrote his famous novel of revolutionary conversion and struggle, Мать (Mat’, The Mother). His experiences there—which included a scandal over his traveling with his lover rather than his wife—deepened his contempt for the "bourgeois soul" but also his admiration for the boldness of the American spirit. While briefly imprisoned in Peter and Paul Fortress during the abortive 1905 Russian Revolution, Gorky wrote the play Children of the Sun, nominally set during an 1862 cholera epidemic, but universally understood to relate to present-day events.

From 1906 to 1913, Gorky lived on the island of Capri, partly for health reasons and partly to escape the increasingly repressive atmosphere in Russia. He continued to support the work of Russian social-democracy, especially the Bolsheviks, and to write fiction and cultural essays. Most controversially, he articulated, along with a few other maverick Bolsheviks, a philosophy he called "God-Building", which sought to recapture the power of myth for the revolution and to create a religious atheism that placed collective humanity where God had been and was imbued with passion, wonderment, moral certainty, and the promise of deliverance from evil, suffering, and even death. Though 'God-Building' was suppressed by Lenin, Gorky retained his belief that "culture"—the moral and spiritual awareness of the value and potential of the human self—would be more critical to the revolution’s success than political or economic arrangements.

An amnesty granted for the 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty allowed Gorky to return to Russia in 1913, where he continued his social criticism, mentored other writers from the common people, and wrote a series of important cultural memoirs, including the first part of his autobiography. On returning to Russia, he wrote that his main impression was that "everyone is so crushed and devoid of God's image." The only solution, he repeatedly declared, was "culture".

During World War I, his apartment in Petrograd was turned into a Bolshevik staff room, but his relations with the Communists turned sour. After his newspaper Novaya Zhizn (Новая Жизнь, "New Life") fell prey to Bolshevik censorship, Gorky published a collection of essays critical of the Bolsheviks called Untimely Thoughts in 1918. (It would not be published in Russia again until the end of the Soviet Union.) The essays call Lenin a tyrant for his senseless arrests and repression of free discourse, and an anarchist for his conspiratorial tactics; Gorky compares Lenin to both the Tsar and Nechayev.

In August 1921, Nikolai Gumilyov, his friend, fellow writer and Anna Akhmatova's husband, was arrested by the Petrograd Cheka for his monarchist views. Gorky hurried to Moscow, obtained an order to release Gumilyov from Lenin personally, but upon his return to Petrograd he found out that Gumilyov had already been shot. In October, Gorky returned to Italy on health grounds: he had tuberculosis.

According to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Gorky's return to the Soviet Union was motivated by material needs. In Sorrento, Gorky found himself without money and without fame. He visited the USSR several times after 1929, and in 1932 Joseph Stalin personally invited him to return for good, an offer he accepted. In June 1929, Gorky visited Solovki (cleaned up for this occasion) and wrote a positive article about that Gulag camp, which had already gained ill fame in the West. Later he stated that everything he had written was under the control of censors. What he actually saw and thought when visiting the camp has been a highly discussed topic.

Gorky's return from Fascist Italy was a major propaganda victory for the Soviets. He was decorated with the Order of Lenin and given a mansion (formerly belonging to the millionaire Ryabushinsky, now the Gorky Museum) in Moscow and a dacha in the suburbs. One of the central Moscow streets, Tverskaya, was renamed in his honor, as was the city of his birth. The largest fixed-wing aircraft in the world in the mid-1930s, the Tupolev ANT-20 (photo), was also named Maxim Gorky. It was used for propaganda purposes and often demonstratively flew over the Soviet capital.

On October 11, 1931 Gorky read his fairy tale "A Girl and Death" to his visitors Joseph Stalin, Kliment Voroshilov and Vyacheslav Molotov, an event that was later depicted by Viktor Govorov on his painting. On that same day Stalin left his autograph on the last page of this work by Gorky:

Эта штука сильнее чем "Фауст" Гёте (любовь побеждает смерть) English: "This piece is stronger than Goethe's Faust (love defeats death)".

In 1933 Gorky edited an infamous book about the White Sea-Baltic Canal, presented as an example of "successful rehabilitation of the former enemies of proletariat".

With the increase of Stalinist repression and especially after the assassination of Sergei Kirov in December 1934, Gorky was placed under unannounced house arrest in his Moscow house.

The sudden death of his son Maxim Peshkov in May 1934 was followed by the death of Maxim Gorky himself in June 1936. Speculation has long surrounded the circumstances of his death. Stalin and Molotov were among those who carried Gorky's coffin during the funeral.

During the Bukharin show trials in 1938, one of the charges was that Gorky was killed by Yagoda's NKVD agents.

In Soviet times, before and after his death, the complexities in Gorky's life and outlook were reduced to an iconic image (echoed in heroic pictures and statues dotting the countryside): Gorky as a great Russian writer who emerged from the common people, a loyal friend of the Bolsheviks, and the founder of the increasingly canonical "socialist realism". In turn, dissident intellectuals dismissed Gorky as a tendentious ideological writer[citation needed], though some Western writers[who?] noted Gorky's doubts and criticisms[citation needed]. Today, greater balance is to be found in works on Gorky, where we see a growing appreciation of the complex moral perspective on modern Russian life expressed in his writings [citation needed]. Some historians [who?] have begun to view Gorky as one of the most insightful observers of both the promises and moral dangers of revolution in Russia.

Selected works

Makar Chudra (Макар Чудра), short story, 1892

Chelkash (Челкаш), 1895

Malva, 1897

Creatures That Once Were Men, stories in English translation (1905)

This contained an introduction by G. K. Chesterton

Twenty-six Men and a Girl

Foma Gordeyev (Фома Гордеев), novel, 1899

Three of Them (Трое), 1900

The Song of the Stormy Petrel (Песня о Буревестнике), 1901

Song of a Falcon (Песня о Соколе),short story, 1902

The Life of Matvei Kozhemyakin (Жизнь Матвея Кожемякина)

The Mother (Мать), novel, 1907

A Confession (Исповедь), 1908

Okurov City (Городок Окуров), novel, 1908

My Childhood (Детство), 1913–1914

In the World (В людях), 1916

Chaliapin, articles in Letopis, 1917

Commemorative coin, released in the USSR on his 120th anniv. features his portrait and a stormy petrel over the storm seaUntimely Thoughts, articles, 1918

My Universities (Мои университеты), 1923

The Artamonov Business (Дело Артамоновых), 1927

Life of Klim Samgin (Жизнь Клима Самгина), epopeia, 1927–36

Reminiscences of Tolstoy (1919), Chekhov (1905–21), and Andreyev

V.I.Lenin (В.И.Ленин), reminiscence, 1924–31

The I.V. Stalin White Sea - Baltic Sea Canal, 1934 (editor-in-chief)

Drama

The Philistines (Мещане), 1901

The Lower Depths (На дне), 1902

Summerfolk (Дачники), 1904

Children of the Sun (Дети солнца), 1905

Barbarians, 1905

Enemies, 1906

Queer People, 1910

Vassa Zheleznova, 1910

The Zykovs, 1913

Counterfeit Money, 1913

Yegor Bulychov and Others, 1932

Dostigayev and Others, 1933

Adaptations

The German modernist theatre practitioner Bertolt Brecht based his epic play The Mother (1932) on Gorky's novel of the same name. Gorky's novel was also adapted for an opera by Valery Zhelobinsky in 1938. In 1912, the Italian composer Giacomo Orefice based his opera Radda on the character of Radda from Makar Chudra.

Works about Gorky

The Gorky Trilogy is a series of three feature films—The Childhood of Maxim Gorky, My Apprenticeship, and My Universities—directed by Mark Donskoi, filmed in the Soviet Union, released 1938-1940. The trilogy was adapted from Gorky's autobiography.

The Murder of Maxim Gorky. A Secret Execution by Arkady Vaksberg. (Enigma Books: New York, 2007. ISBN 978-1-929631-62-9.)

Quotations

"One has to be able to count if only so that at fifty one doesn't marry a girl of twenty"

"Если враг не сдается, его уничтожают" (If the enemy doesn't surrender, he shall be exterminated!)

"When work is a pleasure, life is a joy! When work is duty, life is slavery."

"One miserable being seeks another miserable being; then he's happy."

"Politics is the seedbed of social enmity, evil suspicions, shameless lies, morbid ambitions, and disrespect for the individual. Name anything bad in man, and it is precisely in the soil of political struggle that it grows with abundance."