阅读君特·格拉斯 Günter Grass在小说之家的作品!!! 阅读君特·格拉斯 Günter Grass在诗海的作品!!! | |||||

一九五八年十月,“四七”社在阿德勒饭店聚会。君特·格拉斯,三十一岁。他来了,朗诵了,成功了。他朗诵了长篇小说《铁皮鼓》首章《肥大的裙子》。作品极富想像力,生动、感人、清新,与会作家一致同意授予他“四七社”奖,三千马克。一九五九年秋,美因河畔法兰克福国际书展揭幕,格拉斯和《铁皮鼓》在书展上亮相。他给人的印象是既机智诙谐,又严肃认真。至于对小说的评论,一边是喝彩叫好,一边是一棍子打死。不来梅一个评奖委员会授予格拉斯文学奖,不来梅市政府却又决议反对。然而,小说依然畅销,二十五年内共印了三百多万册,一九六三年前,十一种语言的译本已经问世。一九八○年,被搬上银幕的《铁皮鼓》在美国好莱坞电影节获外国影片奥斯卡奖,电影和小说英译本在美国走红一时。从八十年代末起,《铁皮鼓》又在东欧和经历了一次复兴。这都表明了这部小说的生命力。

一九六一年和一九六三年,格拉斯又发表了中篇小说《猫与鼠》和长篇小说《狗年月》。卢赫特汉德出版社把这两部作品同《铁皮鼓》一起改排重印时,经作者同意加上了“但泽三部曲”这个副标题。这三部小说各自独立,故事与人物均无连续性,因而不是通常意义上的三部曲,但如格拉斯所说,它们有四个共同点:一是从纳粹时期德国人的过错问题着眼写的;二是地点(但泽)和时间(一九二○年至一九五五年)一致;三是真实与虚构交替;四是作者私人的原因:“试图为自己保留一块最终失去的乡土,一块由于、历史原因而失去的乡土”。

出版的诗集有《风信鸡之优点》(1953)、《三角轨道》(1953),其他作品有荒诞剧《洪水》(1957)、《叔叔、叔叔》(1958)、《恶厨师》(1961)、长篇小说《铁皮鼓》等。此外还有《猫与鼠》(1961)、《非常岁月》(1963,亦译《狗的年月》),合称为《但泽三部曲》。长篇小说《鲽鱼》(1977)和《母老鼠》(1986)都继续使用了怪诞讽刺的手法,将现实、幻想、童话、传说融为一体。《蜗牛日记》(1972)则为一部纪实体的文学作品。

He was born in the Free City of Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland). Since 1945, he has lived in (the now former) West Germany, but in his fiction he frequently returns to the Danzig of his childhood.

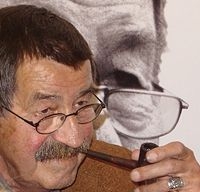

He is best known for his first novel, The Tin Drum, a key text in European magic realism. His works frequently have a strong (left wing, socialist) political dimension, and Grass has been an active supporter of the Social Democratic Party of Germany. In 2006, Grass caused a controversy with his belated disclosure of Waffen-SS service during the final months of World War II.

English-speaking readers probably know Grass best as the author of The Tin Drum (Die Blechtrommel), published in 1959 (and subsequently filmed by director Volker Schlöndorff in 1979). It was followed in 1961 by the novella Cat and Mouse (Katz und Maus) and in 1963 by the novel Dog Years (Hundejahre), which together with The Tin Drum form what is known as The Danzig Trilogy. All three works deal with the rise of Nazism and with the war experience in the unique cultural setting of Danzig and the delta of the Vistula River. Dog Years, in many respects a sequel to The Tin Drum, portrays the area's mixed ethnicities and complex historical background in lyrical prose that is highly evocative.

Grass received dozens of international awards and in 1999 achieved the highest literary honour: the Nobel Prize for Literature. His literature is commonly categorized as part of the artistic movement of Vergangenheitsbewältigung, roughly translated as "coming to terms with the past."

In 2002 Grass returned to the forefront of world literature with Crabwalk (Im Krebsgang). This novella, one of whose main characters first appeared in Cat and Mouse, was Grass' most successful work in decades.

Representatives of the City of Bremen joined together to establish the Günter Grass Foundation, with the aim of establishing a centralized collection of his numerous works, especially his many personal readings, videos and films. The Günter Grass House in Lübeck houses exhibitions of his drawings and sculptures, an archive and a library.

Life

Grass was born in the Free City of Danzig on October 16, 1927, to Willy Grass (1899-1979), a Protestant ethnic German, and Helene Grass (née Knoff, 1898-1954), a Roman Catholic of Kashubian-Polish origin . Grass was raised a Catholic. His parents had a grocery store with an attached apartment in Danzig-Langfuhr (Gdańsk-Wrzeszcz). He has one sister, who was born in 1930.

Grass attended the Danzig Gymnasium Conradinum. He volunteered for submarine service with the Kriegsmarine "to get out of the confinement he felt as a teenager in his parents' house" which he considered - in a very negative way - civic Catholic lower middle class . He was drafted in 1942 into the Reichsarbeitsdienst, and in November 1944 into the Waffen-SS. Grass saw combat with the 10th SS Panzer Division Frundsberg from February 1945 until he was wounded on 20 April 1945 and sent to an American POW camp.

In 1946 and 1947 he worked in a mine and received a stonemason's education. For many years he studied sculpture and graphics, first at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, then at the Universität der Künste Berlin. He also worked as an author and travelled frequently. He married in 1954 and since 1960 has lived in Berlin as well as part-time in Schleswig-Holstein. Divorced in 1978, he remarried in 1979. From 1983 to 1986 he held the presidency of the Berlin Akademie der Künste (Berlin Academy of Arts).

Political activism

Tadeusz Różewicz and Günter Grass, 2006Grass took an active role in the Social-Democratic (SPD) party and supported Willy Brandt's election campaign. He criticised left-wing radicals and instead argued in favour of the "snail's pace", as he put it, of democratic reform (Aus dem Tagebuch einer Schnecke). Books containing his speeches and essays were released throughout his career.

In the 1980s, he became active in the peace movement and visited Calcutta for six months. A diary with drawings was published as Zunge zeigen, an allusion to Kali's tongue.

During the events leading up to the unification of Germany in 1989-90, Grass argued for continued separation of the two German states, asserting that a unified Germany would necessarily resume its role as belligerent nation-state.

In 2001, Grass proposed the creation of a German-Polish museum for art lost during the War. While the Hague Convention of 1907 requires the return of art that had been evacuated, stolen (Nazi plunder) or seized, Poland and Russia (unlike many countries that have cooperated with Germany) refuse to repatriate some of the looted art , thus e.g. the manuscript of the German national anthem is kept in Poland.

Disclosure of Waffen-SS Membership

Günter Grass' prisoner of war record, indicating his membership of a Waffen-SS unit.On 12 August 2006, in an interview about his forthcoming book Peeling the Onion, Grass stated that he had been a member of the Waffen-SS. Before this interview, Grass was seen as someone who had been a typical member of the "Flakhelfer generation," one of those too young to see much fighting or to be involved with the Nazi regime in any way beyond its youth organizations.

On August 15, 2006, the online edition of Der Spiegel, Spiegel Online, published three documents from U.S. forces dating from 1946, verifying Grass's Waffen-SS membership. .

After an unsuccessful attempt to volunteer for the U-Boat fleet at age 15, Grass was conscripted into the Reichsarbeitsdienst (Reich Labor Service), and was then called up for the Waffen-SS in 1944. At that point of the war, youths could be conscripted into the Waffen-SS instead of the army (Wehrmacht); this was unrelated to membership of the SS proper.

Grass was trained as a tank gunner and fought with the 10th SS Panzer Division Frundsberg until its surrender to U.S. forces at Marienbad. In 2007, Grass published an account of his wartime experience in The New Yorker, including an attempt to "string together the circumstances that probably triggered and nourished my decision to enlist.". To the BBC, Grass said in 2006 :

It happened as it did to many of my age. We were in the labour service and all at once, a year later, the call-up notice lay on the table. And only when I got to Dresden did I learn it was the Waffen-SS.

Joachim Fest, conservative German journalist, historian and biographer of Adolf Hitler, told the German weekly Der Spiegel about Grass's disclosure:

After 60 years, this confession comes a bit too late. I can't understand how someone who for decades set himself up as a moral authority, a rather smug one, could pull this off.

However, as Grass has for many decades been an outspoken left-leaning critic of Germany's treatment of its Nazi past, his statement caused a great stir in the press.

Rolf Hochhuth said it was "disgusting" that this same "politically correct" Grass had publicly criticized Helmut Kohl and Ronald Reagan's visit to a military cemetery at Bitburg in 1985, because it also contained graves of Waffen-SS soldiers. In the same vein, the historian Michael Wolffsohn has accused Grass of hypocrisy about not earlier disclosing his SS membership. Also, Christopher Hitchens has pointed out that there have been critics who have called Grass' admission to be merely a publicity stunt to sell more copies of his new book. Many have come to Grass' defense based upon the fact the Waffen-SS membership was very early in Grass' life, and also precisely because he has always been publicly critical of Germany's Nazi past, unlike many of his conservative critics. For example, novelist John Irving has criticised those who would dismiss the achievements of a lifetime because of a mistake made as a teenager.

Grass's biographer Michael Jürgs spoke of "the end of a moral institution" . Lech Wałęsa had initially criticized Grass for keeping silent about his SS membership for 60 years but in a couple of days had publicly withdrawn his criticism after reading the letter of Grass to the mayor of Gdańsk and admitted that Grass "set the good example for the others." On August 14, 2006, the ruling party of Poland, the "Law and Justice" party, called on Grass to relinquish his honorary citizenship of Gdańsk. Jacek Kurski stated, "It is unacceptable for a city where the first blood was shed, where World War II began, to have a Waffen-SS member as an honorary citizen." However, according to a poll ordered by city's authorities, the vast majority of Gdańsk citizens did not support Kurski's position. The mayor of Gdańsk, Paweł Adamowicz, said that he opposed submitting the affair to the municipal council because it was not for the council to judge history.

In September 2006, 46 authors, poets, artists and intellectuals from various Arab countries published a letter of solidarity with Grass, stating that his joining the Waffen-SS was simply a case of a young, misguided teenager doing his duty. The text of the letter made it clear that the authors were not familiar with Grass's works or political views.

Joachim C. Fest, a historian, stated "I don't understand how someone can present himself as the nation's guilty conscience for 60 years and then admit to himself having been deeply involved."[citation needed] Martin Walser, a writer, stated "The most responsible of all contemporaries can not disclose after 60 years that he landed in the Waffen SS through no fault of his own."[citation needed]

Major works

Die Vorzüge der Windhühner (poems, 1956)

Die bösen Köche. Ein Drama (play, 1956)

Hochwasser. Ein Stück in zwei Akten (play, 1957)

Onkel, Onkel. Ein Spiel in vier Akten (play, 1958)

Danziger Trilogie

Die Blechtrommel (1959)

Katz und Maus (1961)

Hundejahre (1963)

Gleisdreieck (poems, 1960)

Die Plebejer proben den Aufstand (play, 1966)

Ausgefragt (poems, 1967)

Über das Selbstverständliche. Reden - Aufsätze - Offene Briefe - Kommentare (speeches, essays, 1968)

Örtlich betäubt (1969)

Aus dem Tagebuch einer Schnecke (1972)

Der Bürger und seine Stimme. Reden Aufsätze Kommentare (speeches, essays, 1974)

Denkzettel. Politische Reden und Aufsätze 1965-1976 (political essays and speeches, 1978)

Der Butt (1977)

Das Treffen in Telgte (1979)

Kopfgeburten oder Die Deutschen sterben aus (1980)

Widerstand lernen. Politische Gegenreden 1980–1983 (political speeches, 1984)

Die Rättin (1986)

Zunge zeigen. Ein Tagebuch in Zeichnungen (1988)

Unkenrufe (1992)

Ein weites Feld (1995)

Mein Jahrhundert (1999)

Im Krebsgang (2002)

Letzte Tänze (poems, 2003)

Beim Häuten der Zwiebel (2006)

Dummer August (poems, 2007)

Die Box (2008)

English translations

The Danzig Trilogy

The Tin Drum (1959)

Cat and Mouse (1963)

Dog Years (1965)

Four Plays (1967)

Speak out! Speeches, Open Letters, Commentaries (1969)

Local Anaesthetic (1970)

From the Diary of a Snail (1973)

In the Egg and Other Poems (1977)

The Meeting at Telgte (1981)

The Flounder (1978)

Headbirths, or, the Germans are Dying Out (1982)

The Rat (1987)

Show Your Tongue (1987)

Two States One Nation? (1990)

The Call of the Toad (1992)

The Plebeians Rehearse the Uprising (1996)

My Century (1999)

Too Far Afield (2000)

Crabwalk (2002)

Peeling the Onion (2007)

References

^ Garland, The Oxford Companion to German Literature, p. 302.

^ "The Literary Encyclopedia", Günter Grass (b. 1927). Retrieved on August 16, 2006.

^ "Katholischen Mief". Source: http://www.zeit.de/2006/34/Leiter-1-34

^ Nobel prize winner Grass admits serving in SS Reuters, Aug 11, 2006

^ Grass, Günter. "How I Spent the War: A recruit in the Waffen S.S.", The New Yorker, 2007-06-04. Retrieved on 2007-05-24. (English)

^ "Grass admits serving in Waffen SS", Reuters, 2006-08-13. Retrieved on 2006-08-13. (English)

^ Hitchens, Christopher. "Snake in the Grass", Slate.com, 2006-08-22. Retrieved on 2006-08-23. (English)

^ "Günter Grass is my hero, as a writer and a moral compass", The Guardian, 2006-08-19. Retrieved on 2006-08-19. (English)

^ Rakowiec, Małgorzata. "Grass asked to give up Polish title", Reuters, 2006-08-14. Retrieved on 2006-08-14. (English)

^ Naggar, Mona. "Arabische Schriftsteller unterstützen Günter Grass", Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 2006-09-14. Retrieved on 2007-04-04. (German)