| míng: | lǐ 'ěr | ||||

| zì: | bó yáng | ||||

yuèdòulǎo zǐ Lao-Tzuzài百家争鸣dezuòpǐn!!! yuèdòulǎo zǐ Lao-Tzuzài诗海dezuòpǐn!!! | |||||

lǎo zǐ de sī xiǎng zhù zhāng shì " wú wéi ", lǎo zǐ de lǐ xiǎng zhèng zhì jìng jiè shì “ lín guó xiāng wàng, jī quǎn zhī shēng xiāng wén, mín zhì lǎo sǐ bù xiāng wǎng lái ”

《 lǎo zǐ》 yǐ“ dào” jiě shì yǔ zhòu wàn wù de yǎn biàn, yǐ wéi“ dào shēng yī, yī shēng 'èr, èr shēng sān, sān shēng wàn wù”,“ dào” nǎi“ fū mò zhī mìng( mìng lìng) ér cháng zì rán”, yīn 'ér“ rén fǎ dì, dì fǎ tiān, tiān fǎ dào, dào fǎ zì rán”。“ dào” wéi kè guān zì rán guī lǜ, tóng shí yòu jù yòu“ dú lì bù gǎi, zhōu xíng 'ér bù dài” de yǒng héng yì yì。《 lǎo zǐ》 shū zhōng bāo kuò dà liàng pǔ sù biàn zhèng fǎ guān diǎn, rú yǐ wéi yī qièshì wù jūn jù yòu zhèng fǎn liǎng miàn,“ fǎn zhě dào zhī dòng”, bìng néng yóu duì lì 'ér zhuǎn huà,“ zhèng fù wéi qí, shàn fù wéi yāo”,“ huò xī fú zhī suǒ yǐ, fú xī huò zhī suǒ fú”。 yòu yǐ wéi shì jiān shì wù jūn wéi“ yòu” yǔ“ wú” zhī tǒng yī,“ yòu、 wú xiāng shēng”, ér“ wú” wéi jī chǔ,“ tiān xià wàn wù shēng yú yòu, yòu shēng yú wú”。“ tiān zhī dào, sǔn yòu yú 'ér bǔ bù zú, rén zhī dào zé bù rán, sǔn bù zú yǐ fèng yòu yú”;“ mín zhī jī, yǐ qí shàng shí shuì zhī duō”;“ mín zhī qīng sǐ, yǐ qí shàng qiú shēng zhī hòu”;“ mín bù wèi sǐ, nài hé yǐ sǐ jù zhī?”。 qí xué shuō duì zhōng guó zhé xué fā zhǎn jù shēn kè yǐng xiǎng, qí nèi róng zhù yào jiàn《 lǎo zǐ》 zhè běn shū。 tā de zhé xué sī xiǎng hé yóu tā chuàng lì de dào jiā xué pài, bù dàn duì wǒ guó gǔ dài sī xiǎng wén huà de fā zhǎn, zuò chū liǎo zhòng yào gòng xiàn, ér qiě duì wǒ guó 2000 duō nián lái sī xiǎng wén huà de fā zhǎn, chǎn shēng liǎo shēn yuǎn de yǐng xiǎng。

yī shuō lǎo zǐ jí tài shǐ dàn, huò lǎo lāi zǐ。《 lǎo zǐ》 yī shū shì fǒu wéi lǎo zǐ suǒ zuò, lì lái yòu zhēng lùn。

《 shǐ jì . lǎo zǐ hán fēi lièzhuàn》 :" guān lìng yǐn xǐ yuē, zǐ jiāng yǐn yǐ, qiáng wéi wǒ zhù shū。 yú shì lǎo zǐ nǎi zhù shū shàng xià piān, yán dào dé zhī yì wǔ qiān yú yán 'ér qù。 " hàn hé shàng gōng zuò《 lǎo zǐ zhāng jù》, fēn wéi bā shí yī zhāng, yǐ qián sān shí qī zhāng wéi《 dào jīng》, hòu sì shí sì zhāng wéi《 dé jīng》, gù yòu《 dào dé jīng》 zhī míng。 dàn 1973 niánzhǎng shā mǎ wáng duī sān hào hàn mù chū tǔ de《 lǎo zǐ》 chāo xiě běn,《 dé jīng》 zài《 dào jīng》 zhī qián。 dào jiào fèng wéi zhù yào jīng diǎn zhī yī。

zài juàn zhì hào fán de zhōng guó shū hǎi dāng zhōng, yòu yī juàn bó 'ér yòu bó kě néng zài guó wài yōng yòu zuì duō de yì zhě hé dú zhě de shū, zhè běn shū míng jiào《 lǎo zǐ》 huò《 dào dé jīng》。《 dào dé jīng》 shì jiě shì dào jiào zhé xué de zhù yào jīng wén。

zhè shì yī běn wēi miào fèi jiě de shū, wén bǐ jí qí yǐn huì, kě yòu xǔ duō bù tóng de jiě shì。“ dào” zhè gè zhù yào gài niàn tōng cháng bèi yì wéi“ fāng fǎ” huò“ dào lù”。 dàn shì zhè gè gài niàn yòu diǎn 'ér hán hú qí cí, yīn wéi《 dào dé jīng》 běn shēn yī kāi shǐ jiù shuō:“ ‘ dào ’, shuō dé chū de, tā jiù bù shì yǒng héng bù biàn de‘ dào’;‘ míng’, jiào dé chū de, tā jiù bù shì yǒng héng bù biàn de‘ míng’。” ① dàn shì wǒ men kě yǐ shuō, dào de dà tǐ yì sī shì“ zì rán” huò“ zì rán fǎ zé”。

dào jiào rèn wéi, rén bù

duì gè rén lái shuō, tōng cháng yìng tí chàng chún pǔ hé zì rán, yìng bì miǎn shǐ yòng bào lì, rú tóng bì miǎn yī qiē zhuī míng zhú lì de xíng wéi yī yàng。 rén men bù

àn zhào zhōng guó de chuán shuō,《 dào dé jīng》 de zuò zhě shì yī wèi míng jiào lǎo zǐ de rén。 jù shuō tā shì kǒng zǐ de tóng shí dài rén, dàn bǐ kǒng zǐ niánzhǎng。 kǒng zǐ shēng huó zài gōng yuán qián liù shì jì, cóng《 dào dé jīng》 de nèi róng hé fēng gé shàng lái kàn, méi yòu jǐ gè xiàn dài xué zhě rèn wéi tā shì zhè me zǎo qī de zuò pǐn; yòu guān gāi shū de shí jì chuàng zuò rì qī wèn tí, cún zài zhe xǔ duō zhēng lùn(《 dào dé jīng》 běn shēn wèi tí dào yī gè jù tǐ de rén wù、 dì diǎn、 rì qī huò lì shǐ shì jiàn)。 dàn shì gōng yuán qián 320 nián shì yī gè kào dé zhù de gū jì ── yǔ shí jì rì qī de wù chā zài bā shí nián yǐ nèi── yě xǔ bǐ zhè gè wù chā fàn wéi hái yào xiǎo dé duō。

zhè gè wèn tí yǐn qǐ liǎo duì yòu guān lǎo zǐ qí rén de shēng zú nián jí shèn zhì duì yòu guān qí rén de zhēn wěi de xǔ duō zhēng lùn。 yòu xiē quán wēi xiāng xìn lǎo zǐ shēng huó zài gōng yuán qián liù shì jì zhè gè chuán shuō, yīn 'ér duàn dìng tā méi yòu xiě《 dào dé jīng》。 qí tā xué zhě zhǐ chū tā zhǐ bù guò shì chuán shuō zhōng de rén wù。 wǒ gè rén de guān diǎn jǐn wéi shǎo shù xué zhě suǒ jiē shòu, wǒ rèn wéi:( 1) lǎo zǐ shí yòu qí rén, shì《 dào dé jīng》 de zuò zhě;( 2) tā shēng huó zài gōng yuán qián sì shì jì;( 3) lǎo zǐ shì kǒng zǐ jiào niánzhǎng de tóng shí dài rén de chuán shuō chún shǔ xū gòu, shì hòu lái de dào jiào zhé xué jiā wéi gěi lǎo zǐ jí qí zhù zuò tú zhī mǒ fěn 'ér biān zào de。

zhí dé zhù yì de shì zài zǎo qī de zhōng guó zuò jiā dāng zhōng, kǒng zǐ( qián 551 héng 479)、 mò dí( qián 5 shì jì) hé mèng zǐ( qián 371 héng 289) jì méi yòu tí dào lǎo zǐ, yě méi yòu tí guò《 dào dé jīng》; dàn shì zhuāng zǐ── yī wèi gōng yuán qián sān shì jì yù mǎn quán guó de dào jiào zhé xué jiā què fǎn fù dì tí dào guò lǎo zǐ。

yóu yú shèn zhì duì lǎo zǐ de cún zài dōuyòu zhēng lùn, wǒ men duì tā de shēng píng xiáng qíng jiù

suī rán dào jiào kāi shǐ shí jī běn shàng shì yī zhǒng fēi zōng jiào zhé xué, dàn shì què zuì zhōng yóu cǐ xiān qǐ liǎo yīcháng zōng jiào yùn dòng。 rán 'ér suī rán zuò wéi yī zhǒng zhé xué de dào jiào jì xù yǐ《 dào dé jīng》 zhōng suǒ biǎo dá de sī xiǎng wéi jī chǔ, dàn shì dào jiào bù jiǔ jiù bèi yún yún zhòng shēng de mí xìn xìn niàn hé xí guàn suǒ náng kuò, zhè xiē xìn niàn hé xí guàn xiāng duì shuō lái tóng lǎo zǐ de shuō jiào méi yòu shénme guān xì。

jiǎ dìng lǎo zǐ shí jì shàng shì《 dào dé jīng》 de zuò zhě, nà me tā de yǐng xiǎng què shí hěn dà。 zhè bù shū suī rán hěnbáo( bù dào liù qiān zhōng wén zì, yīn cǐ zú yǐ yòng yī zhāng bào zhǐ dēngzǎi), dàn què bāo hán zhe xǔ duō jīng shén shí liáng。 zhěng gè xì liè de dào jiào zhé xué jiā dū yòng cǐ shū lái zuò wéi tā men zì jǐ sī xiǎng de qǐ diǎn。

zài xī fāng,《 dào dé jīng》 yuǎn bǐ kǒng zǐ huò rèn hé rú jiā de zuò pǐn liú xíng。 shì shí shàng, gāi shū zhì shǎo chū bǎn guò sì shí zhǒng bù tóng de yīng wén yì běn, chú liǎo《 shèng jīng》 zhī wài yuǎn yuǎn duō yú rèn hé qí tā shū jí de bǎn běn。

zài zhōng guó, rú jiào dà tǐ shàng shì zhàn tǒng zhì dì wèi de zhé xué。 dāng lǎo zǐ hé kǒng zǐ de sī xiǎng zhī jiān chū xiàn xiān míng de duì lì shí, zhōng guó rén dà dū zūn cóng hòu zhě。 dàn shì lǎo zǐ dà tǐ shàng shēn shòu rú jiā dì zǐ de zūn jìng。 kuàng qiě zài xǔ duō qíng kuàng xià, dào jiào sī xiǎng zhí jiē bèi rú jiào sī xiǎng suǒ xī shōu, yīn cǐ duì shù yǐ bǎi wàn jì de zì chēng fēi dào jiào tú de réndōu yòu yǐng xiǎng。 tóng yàng, dào jiào duì yú fó jiào zhé xué, tè bié shì duì chán zōng fó jiào de fā zhǎn yòu zhe xiǎn zhù de yǐng xiǎng。 suī rán jīn tiān méi yòu jǐ gè rén zì chēng shì dào jiào tú, dàn shì chú liǎo kǒng zǐ yǐ wài, zài méi yòu nǎ yī wèi zhōng guó zhé xué jiā duì rén lèi sī xiǎng de yǐng xiǎng xiàng lǎo zǐ nà yàng guǎng fàn hé chí jiǔ。

There are many popular accounts of Laozi's life, though facts and myths are impossible to separate regarding him. He is traditionally regarded as an older contemporary of Confucius, but modern scholarship places him centuries later or questions if he ever existed as an individual. Laozi is regarded as the author of the Dao De Jing, though it has been debated throughout history whether he authored it.

In legends, he was conceived when his mother gazed upon a falling star. It is said that he stayed in the womb and matured for sixty-two years. He was born when his mother leaned against a plum tree. He emerged a grown man with a full grey beard and long earlobes, which are a sign of wisdom and long life.

According to popular biographies, he worked as the Keeper of the Archives for the royal court of Chou. This allowed him broad access to the works of the Yellow Emperor and other classics of the time. Laozi never opened a formal school. Nonetheless, he attracted a large number of students and loyal disciples. There are numerous variations of a story depicting Confucius consulting Laozi about rituals.

Laozi is said to have married and had a son named Tsung, who was a celebrated soldier. A large number of people trace their lineage back to Laozi, as the T'ang Dynasty did. Many, or all, of the lineages may be inaccurate. However, they are a testament to the impact of Laozi on Chinese culture.

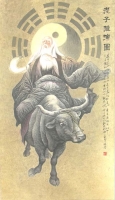

Traditional accounts state that Laozi grew weary of the moral decay of the city and noted the kingdom's decline. At the age of 160, he ventured west to live as a hermit in the unsettled frontier. At the western gate of the city, or kingdom, he was recognized by a guard. The sentry asked the old master to produce a record of his wisdom. The resulting book is said to be the Tao Te Ching. In some versions of the tale, the sentry is so touched by the work that he leaves with Laozi to never be seen again. Some legends elaborate further that the "Old Master" was the teacher of the Buddha, or the Buddha himself.

Laozi is an honorific title. Lao means "venerable" or "old". Zi, or tzu, means "master". Zi was used in ancient China like a social prefix, indicating "Master", or "Sir". In popular biogaphies, Laozi's given name was Er, his surname was Li and his courtesy name was Boyang. Dan is a posthumous name given to Laozi.

During the Tang Dynasty, he was honoured as an ancestor of the dynasty after Taoists drew a connection between the dynasty's family name of Li and Laozi's bearing of the same name. He was granted the title Taishang xuanyuan huangdi, meaning Supreme Mysterious and Primordial Emperor. Xuanyuan and Huangdi are also, respectively, the personal and proper names of the Yellow Emperor.

Laozi's work, the Tao Te Ching, is one of the most significant treatises in Chinese philosophy. It is his magnum opus, covering large areas of philosophy from individual spirituality and inter-personal dynamics to political techniques. The Tao Te Ching is said to contain 'hidden' instructions for Taoist adepts (often in the form of metaphors) relating to Taoist meditation and breathing.

Laozi developed the concept of "Tao", often translated as "the Way", and widened its meaning to an inherent order or property of the universe: "The way Nature is". He highlighted the concept of wu wei, or "do nothing". This does not mean that one should hang around and do nothing, but that one should avoid explicit intentions, strong wills or proactive initiatives.

Laozi believed that violence should be avoided as much as possible, and that military victory should be an occasion for mourning rather than triumphant celebration.

Laozi said that the codification of laws and rules created difficulty and complexity in managing and governing.

As with most other ancient Chinese philosophers, Laozi often explains his ideas by way of paradox, analogy, appropriation of ancient sayings, repetition, symmetry, rhyme, and rhythm. The writings attributed to him are often very dense and poetic. They serve as a starting point for cosmological or introspective meditations. Many of the aesthetic theories of Chinese art are widely grounded in his ideas and those of his most famous follower Zhuang Zi.

Potential officials throughout Chinese history drew on the authority of non-Confucian sages, especially Laozi and Zhuangzi, to deny serving any ruler at any time. Zhuangzi, Laozi's most famous follower, had a great deal of influence on Chinese literati and culture. Zhuangzi is a central authority regarding eremitism, a particular variation of monasticism sacrificing social aspects for religious aspects of life. Zhuangzi considered eremitism the highest ideal, if properly understood.

Scholars such as Aat Vervoom have postulated that Zhuangzi advocated a hermit immersed in society. This view of eremitism holds that seclusion is hiding anonymously in society. To a Zhuangzi hermit, being unknown and drifting freely is a state of mind. This reading is based on the "inner chapters" of Zhuangzi.

Scholars such as James Bellamy hold that this could be true and has been interpreted similarly at various points in Chinese history. However, the "outer chapters" of Zhuangzi have historically played a pivotal role in the advocacy of reclusion. While some scholars state that Laozi was the central figure of Han Dynasty eremitism, historical texts do not seem to support that position.

Political theorists influenced by Laozi have advocated humility in leadership and a restrained approach to statecraft, either for ethical and pacifist reasons, or for tactical ends. In a different context, various anti-authoritarian movements have embraced the Laozi teachings on the power of the weak.

The Anarcho-capitalist economist Murray N. Rothbard suggests that Laozi was the first libertarian, likening Laozi's ideas on government to F.A. Hayek's theory of spontaneous order. Similarly, the Cato Institute's David Boaz includes passages from the Tao Te Ching in his 1997 book The Libertarian Reader. Philosopher Roderick Long, however, argues that libertarian themes in Taoist thought are actually borrowed from earlier Confucian writers.

![老子- 维基百科,自由的百科全书 [编辑] 道教中的老子](http://oson.ca/upload/images11/cache/bd6f091d0f884e90c11c57677b27d48c.jpg)