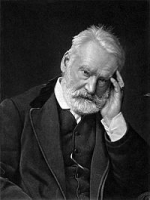

| Victor Marie Hugo | |||||||||||

| 維剋多·馬裏·雨果 | |||||||||||

| 出生地: | 法國的貝藏鬆 | ||||||||||

| 去世地: | 巴黎 | ||||||||||

閱讀維剋多·雨果 Victor Hugo在小说之家的作品!!! 閱讀維剋多·雨果 Victor Hugo在诗海的作品!!! | |||||||||||

1827年發表《剋倫威爾》序言,成為當時浪漫主義運動的重要宣言,雨果本人亦因此而被公認為浪漫主義運動的領袖。其主要詩集有《頌詩集》、《新頌歌集》、《頌詩與長歌》、《東方吟》、《秋葉集》、《黃昏之歌》、《心聲集》、《光與影》、《靜觀集》、史詩《歷代傳說》、《上帝》和《撒旦的末日》。小說最著名的有《九三年》、《巴黎聖母院》和《悲慘世界》。1885年5月22日雨果逝世於巴黎,法蘭西舉國為他志哀。

維剋多·馬裏·雨果(法語:Victor Marie Hugo,法語發音:[viktɔʁ maʁi yɡo] (![]() 聆聽),1802年2月26日-1885年5月22日),法國浪漫主義文學的代表人物和19世紀前期積極浪漫主義文學運動的領袖,法國文學史上卓越的作傢。雨果幾乎經歷了19世紀法國的所有重大事變。一生創作了衆多詩歌、小說、劇本、各種散文和文藝評論及政論文章。代表作有《鐘樓怪人》、《九三年》、和《悲慘世界》等。在法國,雨果主要以詩集紀念,如《靜觀集》和《歷代傳說》。他創作了4000多幅畫,積極參與許多社會運動,如廢除死刑。

聆聽),1802年2月26日-1885年5月22日),法國浪漫主義文學的代表人物和19世紀前期積極浪漫主義文學運動的領袖,法國文學史上卓越的作傢。雨果幾乎經歷了19世紀法國的所有重大事變。一生創作了衆多詩歌、小說、劇本、各種散文和文藝評論及政論文章。代表作有《鐘樓怪人》、《九三年》、和《悲慘世界》等。在法國,雨果主要以詩集紀念,如《靜觀集》和《歷代傳說》。他創作了4000多幅畫,積極參與許多社會運動,如廢除死刑。

生平

1802年2月26日,維剋多·雨果出生於法國東部弗朗什-孔泰地區的杜省貝桑鬆。父親是約瑟夫·萊奧波德·西吉斯貝爾·雨果,母親是索菲·特雷布謝,1772–1821)。雨果是傢中的第三個兒子;他的兄弟為亞伯·約瑟夫·雨果,1798–1855)和尤金·雨果。雨果的父親是一位自由思想共和主義者,視拿破侖為英雄;然而,母親是位天主教保皇主義者,與維剋多·拉奧裏將軍關係密切,後者因密謀反對拿破侖而於1812年處决。

雨果的童年在國傢動蕩中度過。在雨果出生2年後拿破侖稱帝,在他快13歲時波旁復闢。雨果父母的政治宗教觀點對立反映了法國當時的最高爭鬥,並貫穿了他的一生:雨果的父親在西班牙戰役傾覆前,是拿破侖手下的一位高級將軍(這是凱旋門上沒有他的名字的原因)。

由於雨果父親是將軍,傢人不得不常常奔波,雨果從旅行中學到很多。在童年時代,全家前往那不勒斯,看到宏偉的阿爾卑斯山及山上的皚皚白雪,遼闊的藍色地中海,歡度節日的羅馬。雖然當時不過5歲,雨果能清晰地回憶6個月來的旅程。他們在那不勒斯住了幾個月後返回巴黎。

在婚姻之初,雨果的母親索菲和丈夫住在意大利(萊奧波德在那不勒斯附近作省長)和西班牙(管理西班牙三個省)。由於軍旅生涯類轉蓬,加上丈夫不喜歡天主教,索菲在1803年暫時與萊奧波德分居,在巴黎帶孩子。這樣,母親主導了雨果的教育和成長。雨果10歲回巴黎上學,中學畢業入法學院學習,但他的興趣在於寫作,15歲時在法蘭西學院的詩歌競賽會得奬,17歲在“百花詩賽”得第一名,20歲出版詩集《頌詩集》,因歌頌波旁王朝復闢,路易十八賞賜,在這之後他寫了大量異國情調的詩歌。雨果的早期詩賦和小說反映出母親忠君和敬虔的影響。然而,波旁王朝和七月王朝都讓他感到失望,到法國二月革命爆發後,雨果開始反對天主教保皇教育,轉嚮共和主義和自由思想。他還寫過許多詩劇和劇本,幾部具有鮮明特色並貫徹其主張的小說。

年輕的雨果違背母親意思,與青梅竹馬的阿黛爾·福謝訂婚。由於和母親關係密切,倆人直到母親去世(1821年)次年纔結婚。

阿黛爾和維剋多·雨果在1823年生了他們第一位孩子萊奧波德,但孩子不幸夭折。1824年8月28日,第二位孩子萊奧波爾迪娜出生,隨後是1826年11月4日的夏爾、1828年10月28日的弗朗索瓦-維剋多和1830年8月24日的阿黛爾。

雨果的長女,也是他最喜歡的女兒萊奧波爾迪娜於1843年與Charles Vacquerie結婚,但年紀輕輕就慘遭意外。9月4日,二人在維勒基耶泛舟塞納河上時翻船,女兒裙子太沉,直接墜入河底。年輕的女婿在營救時也遭不幸,二人雙雙殞命,萊奧波爾迪娜年僅19歲。當時,雨果正與情人在法國南部旅行,在飯店裏的報紙上讀到這一新聞,悲痛欲絶。著詩À Villequier。

之後,他也寫了不少關於女兒生死方面的詩,至少有一位傳記作傢稱雨果從未從中完全恢復過來。[來源請求]其中,最著名的詩歌大概是《明日清晨》,描述給女兒上墳。

拿破侖三世1851年政變後,雨果决定流亡。離開法國後,雨果於1851年小住布魯塞爾,隨後搬到海峽群島,先去了澤西(1852–1855)後去根西島(1855)。在1870年拿破侖三世倒臺前他一直住在那裏。雖然拿破侖三世在1859年宣佈大赦,雨果可以平安回國,但他沒有這樣做,直到1870年普法戰爭使得拿破侖三世失勢後纔回來。在1870-1871年巴黎圍城之戰時,雨果再次逃到根西島,度過1872-1873年,最後返回法國,度過餘生。

作品

在結婚1年後,雨果出版了第1部小說《冰島兇漢》,3年後出了第2部小說《布格·雅加爾》。在1829到1840年間,他又出了5捲詩集(《東方詩集》、《秋葉集》、《微明之歌》、《心聲集》和《光與影》),為他掙得當時最佳哀歌體和抒情體詩人稱號。

像那個年代許多年輕作傢,雨果深受夏多布裏昂影響,夏多布裏昂是浪漫主義文學運動著名人物,十九世紀法國傑出的文學家。年輕時,雨果决定成為“夏多布裏昂或一無是處”。他的一生與夏多布裏昂有許多類似的地方,雨果進一步推動了浪漫主義,參政(主張共和主義)並因此被迫流亡。

雨果早期作品的熱情與修辭早熟,為他在年輕時就爭得成功和名譽。他第一部詩集《頌詩與雜詠集》於1822年出版,當時他不過20歲,就從路易十八那裏爭得皇傢津貼。雖然,這些詩集因熱情和嫻熟被喜愛,四年後的《頌詩與歌謠》更顯示出雨果是個偉大的詩人,抒情和創意的天才。

維剋多·雨果第一部成熟的小說出現在1829年,反應出他敏銳的社會意識,並貫穿日後的作品。《一個死囚的末日》對後來人,如阿爾貝·加繆、查爾斯·狄更斯和費奧多爾·陀思妥耶夫斯基産生深遠影響。《縲紲盟心》是部有關真實殺人犯在法國處决的紀實短篇小說,於1834年問世,雨果日後認為這是就社會不公的著作《悲慘世界》的前奏。

因戲劇《剋倫威爾》和《艾那尼》,雨果成為浪漫文學運動的領頭人物。

小說《鐘樓怪人》於1831年出版,譯本很快遍布歐洲。小說的一個效果是令巴黎城窘迫,對年久失修的巴黎聖母院進行翻修,後者因小說聞名,訪客絡繹不絶。小說也刺激了對前文藝復興建築的再賞識,令其得到積極保護。

早在三十年代,雨果就打算寫有關社會苦難和不公的大部頭,但《悲慘世界》花了17年纔完成,最終於1862年出版。

在早先的一部小說《一個死囚的末日》中雨果描述了土倫苦役犯從裏出來監獄的場景。1839年,他造訪土倫苦役犯監獄,做了大量筆記,但在1845年前沒有下筆。在有關監獄的一頁筆記裏,他用大字寫了自己的英雄:“JEAN TRÉJEAN”。當故事完成後,Tréjean成了Jean Valjean(冉阿讓)。

雨果對小說的質量有自知之明,1862年3月23日在給他出版商艾伯特·拉剋魯瓦的信中,他說:“我確信如果這不是我最佳作品,那也是高峰作品之一。”《悲慘世界》的出版競價最高。比利時出版商拉剋魯瓦和Verboeckhoven一反常態在出書前6個月就大幅宣傳。最初,小說衹出版第一部分(“芳汀”),在多個主要城市同時出售。小說在幾個小時內售罄,對法國社會産生極大震撼。

批評界最初對小說充滿敵意;依波利特·丹納覺得小說不誠懇,Jules Barbey d'Aurevilly覺得言辭粗俗,古斯塔夫·福樓拜說他“在書中既找不到真理,亦找不到偉大”,龔古爾兄弟指出小說是“人工”的,夏爾·波德萊爾在報紙上稱贊雨果,但在私底下卻痛駡此小說為一部“無味和無能”的作品。大衆則熱烈追捧《悲慘世界》,以至於捧到了國民議會的議題上。今天,小說依然暢銷世界,並多次改編,在電影、電視和舞臺上演。

據不可靠的傳聞,歷史上最短的書信是雨果和出版商赫斯特和布萊剋特在1862年間的回覆。在《悲慘世界》出版時,雨果正在度假。雨果僅以“?”符號打電報給他的英語出版商,以詢問小說的銷情。作為回應,赫斯特和布萊剋特僅以“!”符號電告之,表示銷情很好。

1866年,在隨後的小說《海上勞工》中,雨果避開了社會政治問題。小說反響良好,可能是因為前作《悲慘世界》成功的原因。雨果在英吉利海峽根西島流亡15年,為了紀念此事,雨果講述了一位男子為了博得父愛去營救船衹。船衹被船長偷走,希望能夠帶走其中的財富。小說充滿了人與人、人與海的爭鬥,特別是與神秘的海怪,大烏賊的爭鬥。表面上是個冒險故事,但雨果的一位傳記作傢稱它是“十九世紀的暗喻,技術進步、創造天賦和艱苦勞動剋服物質世界的內在邪惡。”

根西語中的烏賊(pieuvre,有事也指章魚)因本書進入法語。在下一部小說《笑面人》裏,雨果重回政治社會問題。小說於1869年出版,對貴族大加批評。小說不如之前的成功,雨果開始承認自己和文學同行,如古斯塔夫·福樓拜、埃米爾·左拉漸行漸遠,他們的現實主義和自然主義文學已經超越了他自己的風頭。

1874年,最後一部作品《九三年》出版,涉及之前回避的話題:法國大革命時期的恐怖統治。雖然,出版之時雨果的風頭正在走下坡路,如今許多人認為《九三年》是他最佳作品之一。

政治

1841年,雨果在經歷三次失敗後終於入選法蘭西學術院,鞏固了他在法國文藝界的地位。一批法國院士,特別是Victor-Joseph Étienne de Jouy反對“浪漫主義發展”,阻止雨果入選。因此,他更多地參與法國政治。

1845年,雨果被國王路易-菲利普一世封為貴族世卿,進入貴族議員。他發言反對死刑和社會不公,主張出版自由和波蘭自治。

1848年二月革命後,雨果被選為法蘭西第二共和國國民議會保守派議員。1849年,他超越保守派,發表演說呼籲終止不幸與貧睏。其它演說呼籲普選和免費義務教育。雨果對廢除死刑的呼籲國際知名。

這些議會演講可以在《言行錄:流亡以前》找到。查《製憲會議1848》標題和之後頁面。

當路易·拿破侖於1851年政變登基,製定反議會憲法後,雨果公開宣佈拿破侖三世叛國。他流亡布魯塞爾後澤西,澤西一傢報紙批評維多利亞女王,雨果因支持報紙而不得不前往根西聖彼得港的歐特維爾故居(Hauteville House),在那裏從1855年10月住到1870年。在流亡中,雨果發表了反對拿破侖三世的著名政治手册《小拿破侖》和《罪惡史》。這些手册在法國被禁,但依然影響巨大。在根西時,他編撰出版了最佳作品,包括《悲慘世界》,詩集《懲罰集》、《靜觀集》和《歷代傳說》。《懲罰集》每章配有拿破侖三世的一則施政綱領條文,並加以諷刺,還用拿破侖一世的功績和拿破侖三世的恥辱對比。

和那個時代的人一樣,維剋多·雨果支持對非洲殖民。1879年5月18日,他發言稱地中海是“終極文明和[…]終極野蠻”的天然分割,並稱“上帝把非洲給了歐洲。拿下,”以便教化當地居民。這在某種程度上解釋了為什麽他重視並參與政治,但在阿爾及利亞問題上出奇地沉默。他知道法軍在政府阿爾及利亞期間的暴行,並記錄在日記本裏,但他從未公開予以譴責。《萊茵河遊記》出版於1842年,時值法軍登錄阿爾及利亞12年後,現代讀者可能對第17章結尾的意思感到睏惑 :“法國在阿爾及利亞缺的就是一點野蠻。土耳其人[...]比我們更會砍頭。打擊野蠻第一件事不是辯理而是力量。法國缺的英國有;俄國也有。”

值得註意的是在流放之前他從未譴責過奴隸製,在1848年4月27日詳細日記裏沒有發現廢奴的半句話。

另一方面,作為作傢和議員,維剋多·雨果終身為廢除死刑奮鬥。1829年的《一個死囚的末日》分析了犯人行刑前的煎熬;在1830至1885年的日記《隨見錄》裏,他認為死刑是野蠻的行徑;1848年9月15日,在法國二月革命7個月後,他在議會發表演說,稱:“你們已經推翻了王座。[…]現在推翻絞刑架吧。”日內瓦、葡萄牙和哥倫比亞憲法廢除死刑與雨果的努力有關。他也嚮貝尼托·鬍亞雷斯請求赦免剛剛逮捕的墨西哥皇帝馬西米連諾一世,但沒有成功。他的全集(由波維爾出版)顯示他也嚮美國政府緻函,稱為了後者未來的名聲,饒約翰·布朗一命,但信件寄到時布朗已經嗚呼。

雖然拿破侖三世於1859年為所有政治犯大赦,但雨果不願對政府的批評讓步而拒絶接受。1870年法國不流血革命推翻拿破侖三世,第三共和國建立之後,雨果纔於1870年回國,並被選入國民議會。

1870年,普魯士軍隊圍困巴黎城,當時在城中的雨果不得不吃巴黎動物園給他的食物。隨着圍城持續,食物變得更加稀缺,在日記裏他寫道最後不得不“吃莫名的東西”。

1871年3月,巴黎公社起義掌權,5月28日倒臺。維剋多·雨果強烈譴責雙方的暴行。4月9日,他在日記裏寫道:“簡而言之,這個公社是白癡,正如國民議會太殘暴一樣。兩邊都荒唐。”不過,他為遭到殘酷鎮壓的公社成員提供支持。自1871年3月22日起,他在布魯塞爾,他在5月27日比利時報紙《獨立報》上譴責政府拒絶為遭到監禁、流放和處决的公社成員提供政治庇護。這導致騷動,一晚,一群約50人的暴徒試圖強行進入雨果傢,高喊“殺掉雨果!吊死雨果!殺了這個惡棍!”

維剋多·雨果稱:“歐洲之間的戰爭是內戰,”並積極倡導建立歐羅巴合衆國。在1849年巴黎國際和平大會的演講裏,他闡釋了這一觀點。雨果在1856到1870年間流亡根西,1870年7月14日,他在歐特維爾故居花園裏種下“歐羅巴合衆國橡樹”。

由於雨果關心藝術傢權利和版權,他成為國際著作權法學會 創始成員之一,並導致伯爾尼保護文學和藝術作品公約訂立。然而,在波維爾出版的文獻裏,他強烈呼籲:“任何藝術品有兩位作者:有模糊感覺的人,解釋這些感覺的創作者,以及再次推崇這種解釋的人。當一位作者去世後,版權應該完全歸還對方,即人民。”

音樂

雖然雨果博纔多藝,但音樂方面平平,不過他的作品為十九和二十世紀作麯傢提供靈感,對音樂節産生重大影響。雨果自己特別喜歡剋裏斯托夫·格魯剋和卡爾·韋伯的音樂。在《悲慘世界》裏,他在韋伯的《歐良泰》裏稱亨茨曼合唱“大概是譜寫出來的最美妙的音樂”。他也非常喜歡貝多芬,並且在當時不尋常地欣賞上一世紀的作麯傢,如喬瓦尼·帕萊斯特裏納和剋勞迪奧·蒙特威爾第。

十九世紀兩位著名的音樂傢埃剋托·柏遼茲和李斯特·費倫茨是雨果的好友。李斯特在雨果傢裏演奏貝多芬,雨果在給朋友的信中開玩笑說上了李斯特的鋼琴課,他能用一根手指在琴上彈自己最喜歡的麯子。雨果也與作麯傢路易絲-安熱莉剋·貝爾坦合作,根據《鐘樓怪人》主人公編寫1836年劇本《埃斯梅拉達》雖然出於種種原因,歌劇演了5次就沒有繼續下去,對當時的情況人們知之甚少,但現在得到復興。

另一方面,他看不上理查德·瓦格納,說他是:“愚鈍的才子”。

從十九世紀至今,超過1000部音樂作品從雨果那裏獲得靈感。特別是雨果的戲劇離開古典、偏好浪漫,吸引了許多作麯傢改編歌劇。超過100部歌劇源自雨果的作品,如葛塔諾·多尼采蒂的《魯剋蕾齊亞·波吉亞》(1833年),朱塞佩·威爾第的弄臣(1851年)和《埃爾納尼》(1844年),阿米爾卡雷·龐開利的《喬康達》(1876年)。

和戲劇一樣,雨果的小說也成為作麯傢的重要參考,推動他們創作歌劇、芭蕾舞及音樂戲劇如《鐘樓怪人》和《悲慘世界》,後者成為倫敦西區上映最長的音樂劇。另外,雨果詩歌朗朗上口,也為音樂傢所愛,許多歌麯也源自那裏,如柏遼茲、喬治·比纔、加布裏埃爾·福萊、弗蘭剋、愛德華·拉羅、李斯特·費倫茨、儒勒·馬斯內、卡米爾·聖桑、謝爾蓋·拉赫瑪尼諾夫和理查德·瓦格納的作品等。

今天,雨果的作品依然幫助音樂傢進行創作。在根西,每兩年的維剋多·雨果國際音樂節吸引大量音樂傢和作品。值得註意的是,不單單是雨果的文學作品成為音樂創作的靈感,他的政治文獻也受到音樂傢的重視。

繪畫

雨果創作了4,000多幅畫。最開始不過是個興趣愛好,在流亡前不久他停止寫作,專心從政時,花了更多功夫在繪畫上。在1848至1851年間,繪畫成為他唯一的創作發泄。

雨果衹在紙上小幅繪畫;通常用深棕或黑墨筆畫,有時也上白色,但很少用彩色。現存的作品嫻熟的令人吃驚,在風格和處理上很“現代化”,預示了超現實主義和抽象表現主義的實驗技巧。

雨果喜歡用孩子的模板、墨水、膠泥、染色劑、花邊、摺叠、研磨等,常常用火柴棒炭筆或自己的手指畫,而不是用筆或刷子。有時他甚至會用咖啡或煙灰來取得想要的效果。據說,雨果常用左手繪畫,不看紙面,會在唯靈論降神會上用潛意識繪畫。這一概念日後被西格蒙德·弗洛伊德推廣。

雨果沒有把作品公佈,害怕影響他的文學作品。不過,他喜歡給親朋好友看,在政治流亡期間常用裝飾絢爛的手繪卡片當禮物贈與訪客。他的一些作品被當時的藝術傢賞識,如文森特·梵高和歐仁·德拉剋羅瓦;後者稱如果雨果改行當畫傢,定會卓越出衆。

風情

妻子

1822年,雨果迎娶阿黛爾·福謝。他們在一起一共46年,直到她1868年8月去世。此時,雨果依然流亡在外,無法回來參加她在維勒基耶的葬禮,他們的女兒萊奧波爾迪娜也葬在那裏。在1830到1837年間,阿黛爾與評論傢、作傢沙爾-奧古斯丁·聖伯夫有婚外情。

朱麗葉·德魯埃

朱麗葉·德魯埃從1833年2月到她1883年去世時一直追隨雨果,但雨果在妻子1868年去世後沒有再婚。雨果帶她多次出行,朱麗葉也隨他一同流放根西。雨果在他的歐特維爾故居旁邊為她租了小屋。她常給雨果寫情書,直到她75歲去世,將近50年來從未間斷,寫了將近兩萬封信。

萊奧妮·比亞爾

雨果和有夫之婦的萊奧妮·比亞爾(Léonie d’Aunet)糾纏在一起達7年之久。1845年7月5日,雨果在與她私通時被逮了正着。身為貴族院議員,雨果享有豁免權,得以全身而退,但情婦則在監獄待了2個月,在修道院待了6個月。分手數年後,雨果對她提供了經濟支援。

拈花惹草

直到去世幾周前,維剋多·雨果風流不斷,以至於他的傳記人給不出一部完整的花邊合輯。他利用自己的名望、財富和權力隨心所欲地拈花惹草,無論是交際花、演員、妓女、真心仰慕者、少婦、中年婦女、女僕或是像的路易斯·米歇爾革命傢。雨果是個書寫狂和色情狂,像塞繆爾·皮普斯,他使用自己獨創的代碼係統記錄以掩人耳目。例如,他用拉丁語縮寫(osc.:親吻)和西班牙語(Misma. Mismas cosas:同樣,同樣的事)書寫。同音異形異義字更加頻繁:Seins(胸)寫為Saint;Poële(火爐)實際指Poils(陰毛)。他也用類比來隱藏實情:女人的Suisses(瑞士)是她的胸,因為瑞士生産牛奶... 在與少女Laetitia約會後他衹在日記裏寫下Joie(快樂)。如果他加上t.n.(toute nue,全裸)意味着她當面脫了。最後,縮寫如1875年11月的S.B.可能指的是莎拉·伯恩哈特。

晚年

1870年,當雨果回到巴黎時,國傢像歡迎英雄一樣歡迎他。他自以為會被授予獨裁大權,如當時的筆記所寫:“獨裁是犯罪。這個罪我犯了。”雨果認為自己應該承擔責任。雖然人氣頗旺,雨果沒有入選1872年國民議會。

雨果一生堅信人文進步不可阻擋。1879年8月3日,在他最後的公開演講中,他做了過於樂觀的預言:“二十世紀戰爭將消亡,絞刑架會廢除,仇恨會湮滅,邊界綫會取消,教條會廢止;人們會活下來。”

在很短的時間內,雨果輕微中風,他的女兒阿黛爾進了瘋人院,兩個兒子去世。妻子阿黛爾於1868年去世。

他忠實的情婦朱麗葉·德魯埃於1883年去世,先於他兩年離開。雖然親友失散,雨果依然堅持政治改革。1876年1月30日,他被選入新成立的參議院,但這最後的政治事業並不成功。雨果特立獨行,沒有建樹。

1878年6月27日,雨果輕度中風。 1881年2月,在雨果的79歲生日之際,巴黎舉行了盛大的慶祝活動。1881年6月25日,慶祝開始。雨果得到了統治瓷瓶,這是傳統上的貢品。27日,法國歷史上最大的遊行之一開始了。盛大的遊行隊伍從他傢所在的街道經過,穿過香榭麗捨大街直到巴黎中心。遊行持續了6個小時,有60萬他的仰慕者走過他巴黎寓所的窗前。。每一分每一秒都是為了雨果。官方導遊帶着矢車菊,這是《悲慘世界》中芳汀的花。6月28日,巴黎城將d'Eylau大街改為雨果大街。給作者寄信的地址從此變為“緻維剋多·雨果先生,他自己的大街,巴黎”。

去世前兩天,他留下最後的筆記:“愛就是行動”。

1885年5月22日,雨果因患肺炎不治,享年83歲。舉國悲痛哀悼。維剋多·雨果不但是文學巨人,而且是法蘭西第三共和國民主政治傢。他為自由、平等和友愛奮鬥終生,是法國文化堅定的捍衛者。1877年他75歲時,寫道:“我不是那些溫柔的老人之一。我還是感到憤怒和暴力,我喊著,我感到憤慨,我哭了。對任何傷害法國的人來說!我宣佈以狂熱的愛國者的身份去死。”

雖然他要求窮人葬禮,但總統儒勒·格雷維在6月1日為雨果舉行了國葬,舉國緻哀,超過兩百萬人參加了葬禮遊行。他的遺體由窮人的靈車拉着緩緩地被運送到了香榭麗捨盡頭的凱旋門之下,棺上覆蓋着黑紗,被安放在凱旋門下由巴黎歌劇院的設計者夏赫勒·咖赫涅建造的巨大的停靈臺上停靈一夜。之後雨果被安葬在先賢祠,與大仲馬和左拉同睡。許多法國城鎮都有以他命名的街道。

在他去世前兩年在他的遺囑中加上了一條修改附錄:

Je donne cinquante mille francs aux pauvres. Je veux être enterré dans leur corbillard.

Je refuse l'oraison de toutes les Églises. Je demande une prière à toutes les âmes.

Je crois en Dieu.

“我送給窮人們五萬法郎,我希望能用他們的柩車把我送往墓地。

我拒絶任何教堂為我做禱告,我請求所有的靈魂為我祈禱。

我相信上帝。”

宗教思想

雨果的宗教觀點在他一生中改變巨大。年輕時,受母親影響,他認同自己是天主教徒,承認教會制度和權威。爾後,他成為冷淡教友,越來越多地發表反天主教和反教權主義觀點。在流放時,他常常研習唯靈論(他常參加Delphine de Girardin夫人主持的降神會),晚年,他轉信伏爾泰的理智主義自然神論。1872年,人口普查問詢雨果是否是天主教徒時,他回答:“不是,是自由思想者”。

1872年,雨果還是反感天主教會。他認為天主教對工人階級的苦難、對王朝壓迫無動於衷。另一可能是他對教會禁書十分不滿。就天主教會對《悲慘世界》的批判,雨果數了740出。當雨果的兒子夏爾和弗朗索瓦-維剋多去世時,他堅持墓地不要十架苦像,不叫神甫。在遺囑中,他也做出同樣的要求。

不過,他相信來世,每天早晚都會禱告,在《笑面人》中,他寫道:“感恩有翼,飛嚮正地。禱告比你更加識途”。"

雨果的理智主義可以在《托爾剋馬達》(1869年,宗教狂熱主義),《教皇》(1878年,反教權主義),《宗教和宗教》(1880年,反對教會實用性),以及後世出版的《撒旦末日》和《神》(1886年和1891年,其中他將基督教比喻為獅鷲、理智主義為天使)。文森特·梵高將名言“宗教將會消失,但是上帝仍然存在”歸於雨果,其實是儒勒·米什萊所言。

紀念

1959年,法蘭西銀行為了紀念雨果,將其頭像印刷5法郎面值的紙幣上。該紙幣正面背景為其埋葬的先賢祠,背面背景為其生前居住過的孚日廣場。

中文翻譯

- 維剋多‧雨果在中國最初的譯名為囂俄,中國的第一部雨果翻譯是1903年魯迅翻譯的《哀塵》(《隨見錄》Choses vues之節譯),譯者署名為庚辰,刊於《浙江潮》第5期,描寫一善良女子芳梯被一無賴少年頻那夜迦欺侮的故事。

- 1903年,冷血譯西餘𠔌《遊皮》

- 1913年,高君平翻譯囂俄《妙齡,贈彼姝也》

- 1914年,高君平翻譯囂俄《夏之夜二章》

- 1914年,東亞病夫(曾樸)譯《銀瓶怨》(1930年真美善書店出版,又名《項日樂》,Angelo,現譯為《安日樂》)

- 1916年,雪生翻譯《縲紲盟心》(Claude Gueux)

- 1918年,周瘦鵑譯《貧民血》

- 1929年,邱韻鐸譯《死囚之末日》(上海現代書店出版)

- 1830年,曾樸翻譯《歐那尼》(Hernani,現譯為《艾那尼》)

- 1923年,俞忽譯《活冤孽》(1923年4月商務印書館出版)

- 1949年,陳敬容譯《巴黎聖母院》,1949年4月上海駱駝書店出版

- 李丹、方於夫婦從1958年至1984年翻譯《悲慘世界》,這是中國第一套《悲慘世界》全譯本,全部由人民文學出版社出齊(第一捲,1958年;第二捲,1959年;第三、四捲,1980年;第五捲,1984年)。

作品一覽

| 年 | 中文題目 | 原題 |

|---|---|---|

| 1822年 | 頌詩與雜詠集 | Odes et poésies diverses |

| 1823年 | 冰島兇漢 | Han d'Islande |

| 1824年 | 頌詩集 | Nouvelles Odes |

| 1826年 | 比格·雅加爾 | Bug-Jargal |

| 1826年 | 頌詩與歌謠 | Odes et Ballades |

| 1827年 | 剋倫威爾 | Cromwell |

| 1829年 | 東方詩集 | Les Orientales |

| 1829年 | 一個死囚的末日 | Le Dernier jour d'un condamné |

| 1830年 | 埃爾納尼 | Hernani |

| 1831年 | 鐘樓怪人 | Notre-Dame de Paris |

| 1831年 | 瑪麗昂·德洛姆 | Marion Delorme |

| 1831年 | 秋葉集 | Les Feuilles d'automne |

| 1832年 | 國王尋樂 | Le roi s'amuse |

| 1833年 | 盧剋雷齊婭·博爾賈 | Lucrèce Borgia |

| 1833年 | 瑪麗·都鐸 | Marie Tudor |

| 1834年 | 米拉波研究 | Étude sur Mirabeau |

| 1834年 | 文學與哲學論文集 | Littérature et philosophie mêlées |

| 1834年 | 縲紲盟心 | Claude Gueux |

| 1835年 | 安日樂 | Angelo |

| 1835年 | 微明之歌 | Les Chants du crépuscule |

| 1837年 | 心聲集 | Les Voix intérieures |

| 1838年 | 呂·布拉斯 | Ruy Blas |

| 1840年 | 光與影 | Les Rayons et les ombres |

| 1842年 | 萊茵河遊記 | Le Rhin |

| 1843年 | 衛戍官 | Les Burgraves |

| 1852年 | 小拿破侖 | Napoléon le Petit |

| 1853年 | 懲罰集 | Les Châtiments |

| 1855年 | 給路易·波拿巴的信 | Lettres a Louis Bonaparte |

| 1856年 | 靜觀集 | Les Contemplations |

| 1859年 | 歷代傳說 | La Légende des siècles |

| 1862年 | 悲慘世界,又譯悲慘世界(消歧義) | Les Misérables |

| 1864年 | 論威廉·莎士比亞 | William Shakespeare |

| 1865年 | 街與森林之歌 | Les Chansons des rues et des bois |

| 1866年 | 海上勞工 | Les Travailleurs de la Mer |

| 1867年 | 巴黎:巴黎指南前言 | Paris : Préface de Paris Guide |

| 1869年 | 笑面人 | L'Homme qui rit |

| 1872年 | 兇年集 | L'Année terrible |

| 1874年 | 九三年 | Quatrevingt-treize |

| 1874年 | 我的兒子們 | Mes Fils |

| 1875年 | 言行錄:流亡以前 | Actes et paroles – Avant l'exil |

| 1875年 | 言行錄:流亡中 | Actes et paroles – Pendant l'exil |

| 1876年 | 言行錄:流亡以後 | Actes et paroles – Depuis l'exil |

| 1877年 | 歷代傳說 第2 | La Légende des Siècles 2e série |

| 1877年 | 祖父樂 | L'Art d'être grand-père |

| 1877年 | 罪惡史第1部 | Histoire d'un crime 1re partie |

| 1878年 | 罪惡史第2部 | Histoire d'un crime 2e partie |

| 1878年 | 教皇 | Le Pape |

| 1880年 | 宗教與信仰 | Religions et religion |

| 1880年 | 驢子 | L'Âne |

| 1881年 | 靈臺集 | Les Quatres vents de l'esprit |

| 1882年 | 篤爾剋瑪 | Torquemada |

| 1883年 | 歷代傳說 第3 | La Légende des siècles Tome III |

| 1883年 | 英吉利海峽群島 | L'Archipel de la Manche |

畫廊

註釋

- ^ Party of Order

- ^ Independent liberal

- ^ Republican Union

- ^ Adèle Foucher

- ^ Léopold Victor Hugo

- ^ Léopoldine Hugo

- ^ Charles Hugo

- ^ François-Victor Hugo

- ^ Adèle Hugo

- ^ "Victor Hugo" 互聯網檔案館的存檔,存檔日期2015-09-30. Retrieved 22 June 2015

- ^ Renée-Louise Trébuchet

- ^ Jean-François Trébuchet

- ^ Joseph Léopold Sigisbert H.,1774–1828

- ^ Sophie Trébuchet

- ^ Abel Joseph Hugo

- ^ Eugène H.,1800–1837)

- ^ V. Lahorie

- ^ Behr, Edward. The Complete Book of Les Misérables. Arcade Publishing. 1993: 8[2017-03-28]. (原始內容存檔於2017-03-29).

- ^ Josephson, Matthew. Victor Hugo: A Realistic Biography of the Great Romantic. Jorge Pinto Books, Inc. 2006: 4 [2017-03-28]. (原始內容存檔於2017-03-29).

- ^ Victor Hugo, tome 1: Je suis une force qui va by Max Gallo, pub. Broché (2001)

- ^ Demain, dès l'aube

- ^ Émile Bayard

- ^ State Library of Victoria. Victor Hugo: Les Misérables – From Page to Stage research guide. (原始內容存檔於2014-07-14).

- ^ Le Bagne de Toulon (1748-1873), Académie du Var, Autres Temps Editions (2010), ISBN 978-2-84521-394-4

- ^ Albert Lacroix

- ^ 存檔副本. [2017-03-30]. (原始內容存檔於2008-01-08).

- ^ Garson O'Toole, "Briefest Correspondence: Question Mark? Exclamation Mark!" (14 June 2014).

- ^ Hurst and Blackett

- ^ Norris McWhirter (1981). Guinness Book of World Records: 1981 Edition. Bantam Books, p. 216.

- ^ Robb, Graham. Victor Hugo: A Biography. W.W. Norton & Company. 1997: 414[2017-03-30]. (原始內容存檔於2017-03-29).

- ^ On the role of E. de Jouy against V.Hugo, see Les aventures militaires, littéraires et autres de Etienne de Jouy de l'Académie française by Michel Faul (Editions Seguier, France, 2009 ISBN 978-2-84049-556-7)

- ^ Œuvres complètes: actes et paroles I : avant l'exil, 1841–1851

- ^ Assemblée Constituante 1848

- ^ Victor Hugo: Les Misérables – From Page to Stage research guide. State Library of Victoria.[2017-03-31]. (原始內容存檔於2015-04-03).

- ^ Hugo, Victor. Choses Vues. Paris: Gallimard. 1972: 286–287. ISBN 2-07-040217-7.

- ^ Hugo, Victor. Le Rhin. Wikisource.org. [31 January 2017].

- ^ Hugo, Victor. Choses vues. Paris: Gallimard. 1972: 267–269. ISBN 2-07-040217-7.

- ^ Hugo, Victor. Speech on the death penalty. Wikisource.org. 15 September 1848[31 January 2017]. (原始內容存檔於2017-03-29).

- ^ Victor Hugo, l'homme océan. Bibliothèque nationale de France. [19 July 2012]. (原始內容存檔於2017-03-29).

- ^ Pauvert

- ^ Victor Hugo's diary tells how Parisians dined on zoo animals. The Spokesman-Review(Spokane, Washington). 7 February 1915: 3 [2017-03-29]. (原始內容存檔於2017-03-29).

- ^ Hugo, Victor, Choses vues, 1870-1885, Gallimard, 1972, ISBN 2-07-036141-1, p.164

- ^ l’Independance

- ^ 存檔副本. [2017-03-30]. (原始內容存檔於2017-03-29).

- ^ Hugo, Victor, Choses vues, Gallimard, 1972, ISBN 2-07-036141-1, pp. 176-177

- ^ Hugo, Victor, Choses vues, Gallimard, 1972, ISBN 2-07-036141-1, p.258

- ^ International Peace Congress

- ^ Association Littéraire et Artistique Internationale

- ^ Pauvert

- ^ Hugo, V., Les misérables, Volume 2, Penguin Books, 1 December 1980, p.103.

- ^ 51.0 51.1 "Hugo à l'Opéra", ed. Arnaud Laster, L'Avant-Scène Opéra, no. 208 (2002).

- ^ Cette page utilise des cadres 互聯網檔案館的存檔,存檔日期2008-05-08.. Festival international Victor Hugo et Égaux. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- ^ {{{2}}}[[Category:含有非中文內容的條目]]. [2008-04-13]. (原始內容存檔於2008年5月9日). 網址-維基內鏈衝突 (幫助)

- ^ Hugo, Victor, Choses vues, 1870-1885, Gallimard, 1972, p.353, ISBN 2-07-036141-1

- ^ 55.0 55.1 "Hugo et la musique" in Pleins feux sur Victor Hugo, Arnaud Laster, Comédie-Française (1981)

- ^ Juliette Drouet, Evelyn Blewer (Editor), Victoria Tietze Larson (Translator). My Beloved Toto: Letters from Juliette Drouet to Victor Hugo 1833-1882. State University of New York Press (June 2006) ISBN 0-7914-6572-1

- ^ Henri Troyat, 1997. Juliette Drouet: La prisonnière sur parole. Flammarion. ISBN 2-08-067403-X

- ^ Hugo Victor, Choses vues, 1870-1885, Gallimard, 1972, 2-07-036141-1, p.257.

- ^ 存檔副本. [2017-03-31]. (原始內容存檔於2017-03-03).

- ^ Robb, Graham Victor Hugo (1997) p. 506

- ^ Liukkonen, Petri. Victor Hugo. Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: KuusankoskiPublic Library. (原始內容存檔於2014年3月24日).

- ^ Manufacture nationale de Sèvres

- ^ 黃樹芳. 讀書八悟. 朔風. 1992.

- ^ Acte de décès de Victor Hugo 互聯網檔案館的存檔,存檔日期2016-03-03.

- ^ Hugo, Victor, Choses vues 1870-1885, Gallimard, 1972, ISBN 2-07-036141-1, p. 411

- ^ (Charles Garnier)

- ^ 先賢祠之維剋多·雨果的葬禮. [2014-06-14]. (原始內容存檔於2016-03-06).

- ^ Malgras, J. Les Pionniers du Spiritisme en France: Documents pour la formation d'un livre d'Or des Sciences Psychiques. Paris. 1906.

- ^ Chez Victor Hugo. Les tables tournantes de Jersey. Extracts from meeting minutes published by Gustave Simon in 1923

- ^ Gjelten, Tom. Bacardi and the Long Fight for Cuba. Penguin. 2008: 48 [2017-03-14]. (原始內容存檔於2017-03-29).

- ^ Robb, Graham. Victor Hugo. London: Picador. 1997: 32 [2017-03-14]. (原始內容存檔於2017-03-09).

- ^ Petrucelli, Alan. Morbid Curiosity: The Disturbing Demises of the Famous and Infamous. Penguin. 2009: 152 [2017-03-14]. (原始內容存檔於2017-03-09).

- ^ Hugo, Victor, The Man Who Laughs, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2014, ISBN 978-1495441936, p. 132

- ^ Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh. The Hague, between about Wednesday, 13 & about Monday, 18 December 1882. Van Gogh Museum. [31 January 2012]. (原始內容存檔於2018-12-07).

- ^ Caodaism : A Vietnamese-centred religion. [8 May 2009]. (原始內容存檔於2012-06-23).

- ^ 譯者有“題解”:“此囂俄《隨見錄》之一,記一賤女子芳梯事者也。……芳梯者,《哀史》中之一人,生而為無心薄命之賤女子也,復不幸舉一女,閱盡為母之哀,而輾轉苦痛於社會之陷阱者其人也。”

- ^ 阿英稱此劇與馬君武譯《威廉退爾》、陳嘏譯《傀儡家庭》鼎足而三,“可以說是從清末到‘五四’時期最足代表的翻譯劇本”(《晚清文學叢鈔·域外文學譯文捲·敘例》,中華書局1981年版,第3頁)。

- ^ Crépuscule

- ^ Ville avec le pont de Tumbledown

- ^ Pieuvre avec les initiales V.H.

- ^ Le Rocher de l'Ermitage dans un paysage imaginaire

- ^ Le phare

- ^ Gavroche a onze ans

- ^ Gravure du dessin "Orient" pour le récit de Notre Dame de Paris

- ^ Vallée de l'Our près de Bivels, Luxembourg

更多閱讀

- Afran, Charles (1997). “Victor Hugo: French Dramatist” 頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館. Website: Discover France. (Originally published in Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia, 1997, v.9.0.1.) Retrieved November 2005.

- Azurmendi, Joxe, (1985). http://www.jakingunea.com/aldizkaria/artikulua/victor-hugo-euskal-herrian/1670 頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館, Jakin, 37: 137–166. Website: Jakingunea.

- Bates, Alfred (1906). “Victor Hugo” 頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館. Website: Theatre History. (Originally published in The Drama: Its History, Literature and Influence on Civilization, vol. 9. ed. Alfred Bates. London: Historical Publishing Company, 1906. pp. 11–13.) Retrieved November 2005.

- Bates, Alfred (1906). “Hernani” 頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館. Website: Theatre History. (Originally published in The Drama: Its History, Literature and Influence on Civilization, vol. 9. ed. Alfred Bates. London: Historical Publishing Company, 1906. pp. 20–23.) Retrieved November 2005.

- Bates, Alfred (1906). “Hugo's Cromwell” 頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館. Website: Theatre History. (Originally published in The Drama: Its History, Literature and Influence on Civilization, vol. 9. ed. Alfred Bates. London: Historical Publishing Company, 1906. pp. 18–19.) Retrieved November 2005.

- Bittleston, Misha. "Drawings of Victor Hugo". Website: Misha Bittleston. Retrieved November 2005.

- Burnham, I.G. (1896). "Amy Robsart" 頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館. Website: Theatre History. (Originally published in Victor Hugo: Dramas. Philadelphia: The Rittenhouse Press, 1896. pp. 203–6, 401–2.) Retrieved November 2005.

- Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th Edition (2001–05). "Hugo, Victor Marie, Vicomte". Website: Bartleby, Great Books Online. Retrieved November 2005. Retrieved November 2005.

- Haine, W. Scott (1997). "Victor Hugo". Encyclopedia of 1848 Revolutions. Website: Ohio University. Retrieved November 2005.

- Karlins, N.F. (1998). "Octopus With the Initials V.H." 頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館Website: ArtNet. Retrieved November 2005.

- Liukkonen, Petri (2000). Template:Books and Writers

- Meyer, Ronald Bruce (2004). "Victor Hugo". [2017-03-27]. (原始內容存檔於2006-05-08).. Website: Ronald Bruce Meyer. Retrieved November 2005.

- Portasio, Manoel (2009). "Victor Hugo e o Espiritismo" 頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館. Website: Sir William Crookes Spiritist Society. (Portuguese) Retrieved August 2010.

- Robb, Graham (1997). "A Sabre in the Night" 頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館. Website: The New York Times (Books). (Excerpt from Graham, Robb (1997). Victor Hugo: A Biography. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.) Retrieved November 2005.

- Roche, Isabel (2005). "Victor Hugo: Biography". Meet the Writers. Website: Barnes & Noble. (From the Barnes & Noble Classics edition of The Hunchback of Notre Dame, 2005.) Retrieved November 2005.

- Schneider, Maria do Carmo M (2010). http://www.miniweb.com.br/Literatura/Artigos/imagens/victor_hugo/face_oculta.pdf 頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館. Website: MiniWeb Educacao. (Portuguese) Retrieved August 2010.

- State Library of Victoria (2014). "Victor Hugo: Les Misérables – From Page to Stage". Website: Retrieved July 2014.

- Uncited author. "Victor Hugo" 頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館. Website: Spartacus Educational. Retrieved November 2005.

- Uncited author. "Timeline of Victor Hugo" 頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館. Website: BBC. Retrieved November 2005.

- Uncited author. (2000–2005). "Victor Hugo" 頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館. Website: The Literature Network. Retrieved November 2005.

- Uncited author. "Hugo Caricature". Website: Présence de la Littérature a l'école. Retrieved November 2005.

- Barbou, Alfred (1882). Victor Hugo and His Times. University Press of the Pacific: 2001 paper back edition. ISBN 0-89875-478-X

- Barnett, Marva A., ed. (2009). Victor Hugo on Things That Matter: A Reader. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-12245-4

- Brombert, Victor H. (1984). Victor Hugo and the Visionary Novel. Boston: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-93550-0

- Davidson, A.F. (1912). Victor Hugo: His Life and Work. University Press of the Pacific: 2003 paperback edition. ISBN 1-4102-0778-1

- Dow, Leslie Smith (1993). Adele Hugo: La Miserable. Fredericton: Goose Lane Editions. ISBN 0-86492-168-3

- Falkayn, David (2001). Guide to the Life, Times, and Works of Victor Hugo. University Press of the Pacific. ISBN 0-89875-465-8

- Feller, Martin (1988). Der Dichter in der Politik. Victor Hugo und der Deutsch-Französische Krieg von 1870/71. Untersuchungen zum französischen Deutschlandbild und zu Hugos Rezeption in Deutschland. Marburg: Doctoral Dissertation.

- Frey, John Andrew (1999). A Victor Hugo Encyclopedia. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29896-3

- Grant, Elliot (1946). The Career of Victor Hugo. Harvard University Press. Out of print.

- Halsall, A.W. et al. (1998). Victor Hugo and the Romantic Drama. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-4322-4

- Hart, Simon Allen (2004). Lady in the Shadows: The Life and Times of Julie Drouet, Mistress, Companion and Muse to Victor Hugo. Publish American. ISBN 1-4137-1133-2

- Houston, John Porter (1975). Victor Hugo. New York: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0-8057-2443-5

- Hovasse, Jean-Marc (2001), Victor Hugo: Avant l'exil. Paris: Fayard. ISBN 2-213-61094-0

- Hovasse, Jean-Marc (2008), Victor Hugo: Pendant l'exil I. Paris: Fayard. ISBN 2-213-62078-4

- Ireson, J.C. (1997). Victor Hugo: A Companion to His Poetry. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-815799-1

- Maurois, Andre (1956). Olympio: The Life of Victor Hugo. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Maurois, Andre (1966). Victor Hugo and His World. London: Thames and Hudson. Out of print.

- O'Neill, J (編). Romanticism & the school of nature : nineteenth-century drawings and paintings from the Karen B. Cohen collection. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2000[2017-03-27]. (原始內容存檔於2017-03-29). (contains information on Hugo's drawings)

- Robb, Graham (1997). Victor Hugo: A Biography. W.W. Norton & Company: 1999 paperback edition. ISBN 0-393-31899-0, (description/reviews at wwnorton.com)

In France, Hugo's literary reputation rests primarily on his poetic and dramatic output and only secondarily on his novels. Among many volumes of poetry, Les Contemplations and La Légende des siècles stand particularly high in critical esteem, and Hugo is sometimes identified as the greatest French poet. In the English-speaking world his best-known works are the novels Les Misérables and Notre-Dame de Paris (sometimes translated into English as The Hunchback of Notre-Dame).

Though extremely conservative in his youth, Hugo moved to the political left as the decades passed; he became a passionate supporter of republicanism, and his work touches upon most of the political and social issues and artistic trends of his time. He is buried in the Panthéon.

Victor-Marie Hugo was the third and last son of Joseph Léopold Sigisbert Hugo (1773–1828) and Sophie Trébuchet (1772-1821); his brothers were Abel Joseph Hugo (1798–1855) and Eugène Hugo (1800–1837). He was born in 1802 in Besançon (in the region of Franche-Comté) and lived in France for the majority of his life. However, he was forced into exile during the reign of Napoleon III — he lived briefly in Brussels during 1851; in Jersey from 1852 to 1855; and in Guernsey from 1855 to 1870 and again in 1872-1873. There was a general amnesty in 1859; after that, his exile was by choice.

Hugo's early childhood was marked by great events. The century prior to his birth saw the overthrow of the Bourbon Dynasty in the French Revolution, the rise and fall of the First Republic, and the rise of the First French Empire and dictatorship under Napoleon Bonaparte. Napoleon was proclaimed Emperor two years after Hugo's birth, and the Bourbon Monarchy was restored before his eighteenth birthday. The opposing political and religious views of Hugo's parents reflected the forces that would battle for supremacy in France throughout his life: Hugo's father was a high-ranking officer in Napoleon's army, an atheist republican who considered Napoleon a hero; his mother was a staunch Catholic Royalist who is believed to have taken as her lover General Victor Lahorie, who was executed in 1812 for plotting against Napoleon.

Sophie followed her husband to posts in Italy (where Léopold served as a governor of a province near Naples) and Spain (where he took charge of three Spanish provinces). Weary of the constant moving required by military life, and at odds with her unfaithful husband, Sophie separated temporarily from Léopold in 1803 and settled in Paris. Thereafter she dominated Hugo's education and upbringing. As a result, Hugo's early work in poetry and fiction reflect a passionate devotion to both King and Faith. It was only later, during the events leading up to France's 1848 Revolution, that he would begin to rebel against his Catholic Royalist education and instead champion Republicanism and Freethought.

Early poetry and fiction

Like many young writers of his generation, Hugo was profoundly influenced by François-René de Chateaubriand, the famous figure in the literary movement of Romanticism and France’s preëminent literary figure during the early 1800s. In his youth, Hugo resolved to be “Chateaubriand or nothing,” and his life would come to parallel that of his predecessor’s in many ways. Like Chateaubriand, Hugo would further the cause of Romanticism, become involved in politics as a champion of Republicanism, and be forced into exile due to his political stances.

The precocious passion and eloquence of Hugo's early work brought success and fame at an early age. His first collection of poetry (Nouvelles Odes et Poésies Diverses) was published in 1824, when Hugo was only twenty two years old, and earned him a royal pension from Louis XVIII. Though the poems were admired for their spontaneous fervor and fluency, it was the collection that followed two years later in 1826 (Odes et Ballades) that revealed Hugo to be a great poet, a natural master of lyric and creative song.

Against his mother's wishes, young Victor fell in love and became secretly engaged to his childhood friend Adèle Foucher (1803-1868). Unusually close to his mother, it was only after her death in 1821 that he felt free to marry Adèle (in 1822). They had their first child Léopold in 1823, but the boy died in infancy. Hugo's other children were Léopoldine (August 28, 1824), Charles (November 4, 1826), François-Victor (October 28, 1828) and Adèle (August 24, 1830). Hugo published his first novel the following year (Han d'Islande, 1823), and his second three years later (Bug-Jargal, 1826). Between 1829 and 1840 he would publish five more volumes of poetry (Les Orientales, 1829; Les Feuilles d'automne, 1831; Les Chants du crépuscule, 1835; Les Voix intérieures, 1837; and Les Rayons et les ombres, 1840), cementing his reputation as one of the greatest elegiac and lyric poets of his time.

Mature fiction

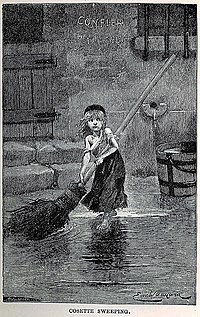

Illustration by Alfred Barbou from the original edition of Notre Dame de Paris (1831)Victor Hugo's first mature work of fiction appeared in 1829, and reflected the acute social conscience that would infuse his later work. Le Dernier jour d'un condamné (Last Days of a Condemned Man) would have a profound influence on later writers such as Albert Camus, Charles Dickens, and Fyodor Dostoevsky. Claude Gueux, a documentary short story about a real-life murderer who had been executed in France, appeared in 1834, and was later considered by Hugo himself to be a precursor to his great work on social injustice, Les Misérables. But Hugo’s first full-length novel would be the enormously successful Notre-Dame de Paris (The Hunchback of Notre Dame), which was published in 1831 and quickly translated into other languages across Europe. One of the effects of the novel was to shame the City of Paris to undertake a restoration of the much-neglected Cathedral of Notre Dame, which was attracting thousands of tourists who had read the popular novel. The book also inspired a renewed appreciation for pre-renaissance buildings, which thereafter began to be actively preserved.

Portrait of "Cosette" by Émile Bayard, from the original edition of Les Misérables (1862)Hugo began planning a major novel about social misery and injustice as early as the 1830s, but it would take a full 17 years for his most enduringly popular work, Les Misérables, to be realized and finally published in 1862. The author was acutely aware of the quality of the novel and publication of the work went to the highest bidder. The Belgian publishing house Lacroix and Verboeckhoven undertook a marketing campaign unusual for the time, issuing press releases about the work a full six months before the launch. It also initially published only the first part of the novel (“Fantine”), which was launched simultaneously in major cities. Installments of the book sold out within hours, and had enormous impact on French society. The critical establishment was generally hostile to the novel; Taine found it insincere, Barbey d'Aurevilly complained of its vulgarity, Flaubert found within it "neither truth nor greatness," the Goncourts lambasted its artificiality, and Baudelaire - despite giving favorable reviews in newspapers - castigated it in private as "tasteless and inept." Nonetheless, Les Misérables proved popular enough with the masses that the issues it highlighted were soon on the agenda of the French National Assembly. Today the novel remains popular worldwide, adapted for cinema, television and musical stage to an extent equaled by few other works of literature.

The shortest correspondence in history is between Hugo and his publisher Hurst & Blackett in 1862. It is said Hugo was on vacation when Les Misérables (which is over 1200 pages) was published. He telegraphed the single-character message '?' to his publisher, who replied with a single '!'.

Hugo turned away from social/political issues in his next novel, Les Travailleurs de la Mer (Toilers of the Sea), published in 1866. Nonetheless, the book was well received, perhaps due to the previous success of Les Misérables. Dedicated to the channel island of Guernsey where he spent 15 years of exile, Hugo’s depiction of Man’s battle with the sea and the horrible creatures lurking beneath its depths spawned an unusual fad in Paris: Squids. From squid dishes and exhibitions, to squid hats and parties, Parisiennes became fascinated by these unusual sea creatures, which at the time were still considered by many to be mythical. The Guernsey word used in the book has also been used to refer to the octopus.

Hugo returned to political and social issues in his next novel, L'Homme Qui Rit (The Man Who Laughs), which was published in 1869 and painted a critical picture of the aristocracy. However, the novel was not as successful as his previous efforts, and Hugo himself began to comment on the growing distance between himself and literary contemporaries such as Flaubert and Zola, whose realist and naturalist novels were now exceeding the popularity of his own work. His last novel, Quatrevingt-treize (Ninety-Three), published in 1874, dealt with a subject that Hugo had previously avoided: the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution. Though Hugo’s popularity was on the decline at the time of its publication, many now consider Ninety-Three to be a work on par with Hugo’s better-known novels.

Political life and exile

After three unsuccessful attempts, Hugo was finally elected to the Académie française in 1841, solidifying his position in the world of French arts and letters. Thereafter he became increasingly involved in French politics as a supporter of the Republic form of government. He was elevated to the peerage by King Louis-Philippe in 1841 and entered the Higher Chamber as a pair de France, where he spoke against the death penalty and social injustice, and in favour of freedom of the press and self-government for Poland. He was later elected to the Legislative Assembly and the Constitutional Assembly, following the 1848 Revolution and the formation of the Second Republic.

Among the Rocks on Jersey (1853-55)When Louis Napoleon (Napoleon III) seized complete power in 1851, establishing an anti-parliamentary constitution, Hugo openly declared him a traitor of France. He fled to Brussels, then Jersey, and finally settled with his family on the channel island of Guernsey at Hauteville House, where he would live in exile until 1870.

While in exile, Hugo published his famous political pamphlets against Napoleon III, Napoléon le Petit and Histoire d'un crime. The pamphlets were banned in France, but nonetheless had a strong impact there. He also composed some of his best work during his period in Guernsey, including Les Misérables, and three widely praised collections of poetry (Les Châtiments, 1853; Les Contemplations, 1856; and La Légende des siècles, 1859).

He convinced the government of Queen Victoria to spare the lives of six Irish people convicted of terrorist activities and his influence was credited in the removal of the death penalty from the constitutions of Geneva, Portugal and Colombia.

Although Napoleon III granted an amnesty to all political exiles in 1859, Hugo declined, as it meant he would have to curtail his criticisms of the government. It was only after Napoleon III fell from power and the Third Republic was proclaimed that Hugo finally returned to his homeland in 1870, where he was promptly elected to the National Assembly and the Senate.

He was in Paris during the siege by the Prussian army in 1870, famously eating animals given him by the Paris zoo. As the siege continued, and food became ever more scarce, he wrote in his diary that they were now reduced to eating things even though he was not at all sure what it was: "we are eating the unknown," he wrote.

Because of his concern for the rights of artists and copyright, he was a founding member of the Association Littéraire et Artistique Internationale, which led to the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works.

Religious views

Hugo's religious views changed radically over the course of his life. In his youth, he identified as a Catholic and professed respect for Church hierarchy and authority. From there he evolved into a non-practicing Catholic, and expressed increasingly violent anti-papist and anti-clerical views. He dabbled in Spiritualism during his exile (where he participated also in seances), and in later years settled into a Rationalist Deism similar to that espoused by Voltaire. When a census-taker asked Hugo in 1872 if he was a Catholic, he replied, "No. A Freethinker".

Hugo never lost his antipathy towards the Roman Catholic Church, due largely to what he saw as the Church's indifference to the plight of the working class under the oppression of the monarchy; and perhaps also due to the frequency with which Hugo's work appeared on the Pope's list of "proscribed books" (Hugo counted 740 attacks on Les Misérables in the Catholic press). On the deaths of his sons Charles and François-Victor, he insisted that they be buried without crucifix or priest, and in his will made the same stipulation about his own death and funeral. However, although Hugo believed Catholic dogma to be outdated and dying, he never directly attacked the institution itself. He also remained a deeply religious man who strongly believed in the power and necessity of prayer.

Hugo's Rationalism can be found in poems such as Torquemada (1869, about religious fanaticism), The Pope (1878, violently anti-clerical), Religions and Religion (1880, denying the usefulness of churches) and, published posthumously, The End of Satan and God (1886 and 1891 respectively, in which he represents Christianity as a griffin and Rationalism as an angel).

"Religions pass away, but God remains", Hugo declared. Christianity would eventually disappear, he predicted, but people would still believe in "God, Soul, and the Power."

Victor Hugo and Music

Although Hugo's many talents did not include exceptional musical ability, he nevertheless had a great impact on the music world through the endless inspiration that his works provided for composers of the 19th and 20th century. Hugo himself particularly enjoyed the music of Gluck and Weber and greatly admired Beethoven, and rather unusually for his time, he also appreciated works by composers from earlier centuries such as Palestrina and Monteverdi. Two famous musicians of the 19th century were friends of Hugo: Berlioz and Liszt. The latter played Beethoven in Hugo’s home, and Hugo joked in a letter to a friend that thanks to Liszt’s piano lessons, he learned how to play a favourite song on the piano – even though only with one finger! Hugo also worked with composer Louise Bertin, writing the libretto for her 1836 opera La Esmeralda which was based on Hugo’s novel Notre-Dame de Paris. Although for various reasons this beautiful and original opera closed soon after its fifth performance and is little known today, it has been recently enjoying a revival, both in a piano/song concert version by Liszt at the Festival international Victor Hugo et Égaux 2007 and in a full orchestral version to be presented in July 2008 at Le Festival de Radio France et Montpellier Languedoc-Roussillon.

Well over one thousand musical compositions have been inspired by Hugo’s works from the 1800s until the present day. In particular, Hugo’s plays, in which he rejected the rules of classical theatre in favour of romantic drama, attracted the interest of many composers who adapted them into operas. More than one hundred operas are based on Hugo’s works and among them are Donizetti’s Lucrezia Borgia (1833), Verdi’s Rigoletto (1851) and Ernani (1844), and Ponchielli’s La Gioconda (1876). Hugo’s novels as well as his plays have been a great source of inspiration for musicians, stirring them to create not only opera and ballet but musical theatre such as Notre-Dame de Paris and the ever-popular Les Misérables, London West End’s longest running musical. Additionally, Hugo’s beautiful poems have attracted an exceptional amount of interest from musicians, and numerous melodies have been based on his poetry by composers such as Berlioz, Bizet, Fauré, Franck, Lalo, Liszt, Massenet, Saint-Saëns, Rachmaninov and Wagner.

Today, Hugo’s work continues to stimulate musicians to create new compositions. For example, Hugo’s novel against capital punishment, Le Dernier Jour d'un condamné (Last Day of a Condemned Man) has recently been adapted into an opera by David Alagna (libretto by Frédérico Alagna). Their brother, tenor Roberto Alagna, performed in the opera’s premiere in Paris in the summer of 2007 and again in February 2008 in Valencia with Erwin Schrott as part of the Festival international Victor Hugo et Égaux 2008.

Sources: “Hugo et la musique” in Pleins feux sur Victor Hugo, Arnaud Laster, Comédie-Française (1981) and “Hugo à l'Opéra”, ed. Arnaud Laster, L'Avant-Scène Opéra, no. 208 (2002).

Declining years and death

Please help improve this article or section by expanding it.

Further information might be found on the talk page or at requests for expansion. (March 2008)

Victor Hugo, by Alphonse Legros.When Hugo returned to Paris in 1870, the country hailed him as a national hero. Despite his popularity Hugo lost his bid for reelection to the National Assembly in 1872. Within a brief period, he suffered a mild stroke, his daughter Adèle’s internment in an insane asylum, and the death of his two sons. (His other daughter, Léopoldine, had drowned in a boating accident in 1843, and his wife Adèle had died in 1868. His faithful mistress, Juliette Drouet, died in 1883, only two years before his own death.) Despite his personal loss, Hugo remained committed to the cause of political change. On 30 January 1876 Hugo was elected to the newly created Senate. His last phase in his political career is considered a failure. Hugo took on a stubborn role and got little done in the Senate.

In February of 1881 Hugo celebrated his 79th birthday. To honor the fact that he was entering his eightieth year, one of the greatest tributes to a living writer was held. The celebrations began on the 25th when Hugo was presented with a Sèvres vase, the traditional gift for sovereigns. On the 27th one of the largest parades in French history was held. Marchers stretched from Avenue d'Eylau, down the Champs-Élysées, and all the way to the center of Paris. The paraders marched for six hours to pass Hugo as he sat in the window at his house. Every inch and detail of the event was for Hugo; the official guides even wore cornflowers as an allusion to Cosette's song in Les Misérables.

Victor Hugo's death on 22 May 1885, at the age of 83, generated intense national mourning. He was not only revered as a towering figure in French literature, but also internationally acknowledged as a statesman who had helped preserve and shape the Third Republic and democracy in France. More than two million people joined his funeral procession in Paris from the Arc de Triomphe to the Panthéon, where he was buried.

Drawings

Many are not aware that Hugo was almost as prolific in the visual arts as he was in literature, producing more than 4,000 drawings in his lifetime. Originally pursued as a casual hobby, drawing became more important to Hugo shortly before his exile, when he made the decision to stop writing in order to devote himself to politics. Drawing became his exclusive creative outlet during the period 1848-1851.

Hugo worked only on paper, and on a small scale; usually in dark brown or black pen-and-ink wash, sometimes with touches of white, and rarely with color. The surviving drawings are surprisingly accomplished and "modern" in their style and execution, foreshadowing the experimental techniques of Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism.

He would not hesitate to use his children's stencils, ink blots, puddles and stains, lace impressions, "pliage" or folding (i.e. Rorschach blots), "grattage" or rubbing, often using the charcoal from match sticks or his fingers instead of pen or brush. Sometimes he would even toss in coffee or soot to get the effects he wanted. It is reported that Hugo often drew with his left hand or without looking at the page, or during Spiritualist séances, in order to access his unconscious mind, a concept only later popularized by Sigmund Freud.

Hugo kept his artwork out of the public eye, fearing it would overshadow his literary work. However, he enjoyed sharing his drawings with his family and friends, often in the form of ornately handmade calling cards, many of which were given as gifts to visitors when he was in political exile. Some of his work was shown to, and appreciated by, contemporary artists such as Van Gogh and Delacroix; the latter expressed the opinion that if Hugo had decided to become a painter instead of a writer, he would have outshone the artists of their century.

Gallery:

Crépuscule ("Twilight"), Jersey, 1853-1855.

Ville avec le pont de Tumbledown, 1847.

Pieuvre avec les initales V.H., ("Octopus with the initials V.H."), 1866.

Le Rocher de l'Ermitage dans un paysage imaginaire ("Hermitage Rock in an Imaginary Landscape")

Le phare ("The Lighthouse")

Additional images of graphic works by Victor Hugo may be viewed at:

Patador & Co.

ArtNet

Misha Bittleston

Memorials

Victor Hugo cabinet card by London Stereoscopic CompanyThe people of Guernsey erected a statue in Candie Gardens to commemorate his stay in the islands.

The City of Paris has preserved his residences Hauteville House, Guernsey and 6, Place des Vosges, Paris as museums. The house where he stayed in Vianden, Luxembourg, in 1871 has also become a commemorative museum.

Hugo is venerated as a saint in the Vietnamese religion of Cao Dai.

The Avenue Victor-Hugo in the XVIème arrondissement of Paris bears Hugo's name, and links the Place de l'Étoile to the vicinity of the Bois de Boulogne by way of the Place Victor-Hugo. This square is served by a Paris Métro stop also named in his honor. A number of streets and avenues throughout France are likewise named after him.

The school Lycée Victor Hugo in his town of birth, Besançon in France.

Avenue Victor-Hugo, located in Shawinigan, Quebec, Canada, was named to honor him.

In the city of Avellino, Italy, Victor Hugo lived briefly stayed in what is now known as Il Palazzo Culturale, when reuniting with his father, Leopold Sigisbert Hugo, in 1808. Victor would later write about his brief stay here quoting "C’était un palais de marbre...".

Works

French literature

By category

French literary history

Medieval

16th century · 17th century

18th century · 19th century

20th century · Contemporary

French writers

Chronological list

Writers by category

Novelists · Playwrights

Poets · Essayists

Short story writers

France portal

Literature portal

This box: view • talk • edit

Published during Hugo's lifetime

Odes et Poésies Diverses (1822)

Odes (1823)

Han d'Islande (1823) (Hans of Iceland)

Nouvelles Odes (1824)

Bug-Jargal (1826)

Odes et Ballades (1826)

Cromwell (1827)

Les Orientales (1829)

Le Dernier jour d'un condamné (1829)

Hernani (1830)

Notre-Dame de Paris (1831), (The Hunchback of Notre Dame)

Marion Delorme (1831)

Les Feuilles d'automne (1831)

Le roi s'amuse (1832)

Lucrèce Borgia (1833) (Lucretia Borgia)

Marie Tudor (1833)

Littérature et philosophie mêlées (1834)

Claude Gueux (1834)

Angelo, tyran de padoue (1835)

Les Chants du crépuscule (1835)

La Esmeralda (only libretto of an opera written by Victor Hugo himself) (1836)

Les Voix intérieures (1837)

Ruy Blas (1838)

Les Rayons et les ombres (1840)

Le Rhin (1842)

Les Burgraves (1843)

Napoléon le Petit (1852)

Les Châtiments (1853)

Les Contemplations (1856)

La Légende des siècles (1859)

Les Misérables (1862)

William Shakespeare (1864)

Les Chansons des rues et des bois (1865)

Les Travailleurs de la Mer (1866), (Toilers of the Sea)

La voix de Guernsey (1867)

L'Homme qui rit (1869), (The Man Who Laughs)

L'Année terrible (1872)

Quatrevingt-treize (Ninety-Three) (1874)

Mes Fils (1874)

Actes et paroles — Avant l'exil (1875)

Actes et paroles - Pendant l'exil (1875)

Actes et paroles - Depuis l'exil (1876)

La Légende des Siècles 2e série (1877)

L'Art d'être grand-père (1877)

Histoire d'un crime 1re partie (1877)

Histoire d'un crime 2e partie (1878)

Le Pape (1878)

La pitié suprême (1879)

Religions et religion (1880)

L'Âne (1880)

Les Quatres vents de l'esprit (1881)

Torquemada (1882)

La Légende des siècles Tome III (1883)

L'Archipel de la Manche (1883)

Poems of Victor Hugo

Published posthumously

Théâtre en liberté (1886)

La fin de Satan (1886)

Choses vues (1887)

Toute la lyre (1888)

Amy Robsart (1889)

Les Jumeaux (1889)

Actes et Paroles Depuis l'exil, 1876-1885 (1889)

Alpes et Pyrénées (1890)

Dieu (1891)

France et Belgique (1892)

Toute la lyre - dernière série (1893)

Correspondences - Tome I (1896)

Correspondences - Tome II (1898)

Les années funestes (1898)

Choses vues - nouvelle série (1900)

Post-scriptum de ma vie (1901)

Dernière Gerbe (1902)

Mille francs de récompense (1934)

Océan. Tas de pierres (1942)

L'Intervention (1951)

Conversations with Eternity

Online texts

Works by Victor Hugo at Project Gutenberg

Works by Victor Hugo at Internet Archive

Works by Victor Hugo at The Online Books Page

Political speeches by Victor Hugo: Victor Hugo, My Revenge is Fraternity!

Biography and speech from 1851

Obituary in The Times

Influence in Brazil

Victor Hugo's works, both in the original and in translation to Portuguese, are considered to have deeply influenced the Brazilian late 19th century literary movement known as condoreirismo, which is marked by the introspection of the Romantic period with a social and humanitarian concern. Particularly considered to have been influenced by Hugo is the well-known abolitionist poet Castro Alves.

References

^ Victor Hugo, l'homme océan

^ http://www.religioustolerance.org/caodaism.htm

Online references

Afran, Charles (1997). “Victor Hugo: French Dramatist”. Website: Discover France. (Originally published in Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia, 1997, v.9.0.1.) Retrieved November 2005.

Bates, Alfred (1906). “Victor Hugo”. Website: Theatre History. (Originally published in The Drama: Its History, Literature and Influence on Civilization, vol. 9. ed. Alfred Bates. London: Historical Publishing Company, 1906. pp. 11-13.) Retrieved November 2005.

Bates, Alfred (1906). “Hernani”. Website: Theatre History. (Originally published in The Drama: Its History, Literature and Influence on Civilization, vol. 9. ed. Alfred Bates. London: Historical Publishing Company, 1906. pp. 20-23.) Retrieved November 2005.

Bates, Alfred (1906). “Hugo’s Cromwell”. Website: Theatre History. (Originally published in The Drama: Its History, Literature and Influence on Civilization, vol. 9. ed. Alfred Bates. London: Historical Publishing Company, 1906. pp. 18-19.) Retrieved November 2005.

Bittleston, Misha (uncited date). "Drawings of Victor Hugo". Website: Misha Bittleston. Retrieved November 2005.

Burnham, I.G. (1896). “Amy Robsart”. Website: Theatre History. (Originally published in Victor Hugo: Dramas. Philadelphia: The Rittenhouse Press, 1896. pp. 203-6, 401-2.) Retrieved November 2005.

Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th Edition (2001-05). “Hugo, Victor Marie, Vicomte”. Website: Bartleby, Great Books Online. Retrieved November 2005. Retrieved November 2005.

Haine, W. Scott (1997). “Victor Hugo”. Encyclopedia of 1848 Revolutions. Website: Ohio University. Retrieved November 2005.

Illi, Peter (2001-2004). “Victor Hugo: Plays”. Website: The Victor Hugo Website. Retrieved November 2005.

Karlins, N.F. (1998). "Octopus With the Initials V.H." Website: ArtNet. Retrieved November 2005.

Liukkonen, Petri (2000). “Victor Hugo (1802-1885)”. Books and Writers. Website: Pegasos: A Literature Related Resource Site. Retrieved November 2005.

Meyer, Ronald Bruce (2004). “Victor Hugo”. Website: Ronald Bruce Meyer. Retrieved November 2005.

Robb, Graham (1997). “A Sabre in the Night”. Website: New York Times (Books). (Excerpt from Graham, Robb (1997). Victor Hugo: A Biography. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.) Retrieved November 2005.

Roche, Isabel (2005). “Victor Hugo: Biography”. Meet the Writers. Website: Barnes & Noble. (From the Barnes & Noble Classics edition of The Hunchback of Notre Dame, 2005.) Retrieved November 2005.

Uncited Author. “Victor Hugo”. Website: Spartacus Educational. Retrieved November 2005.

Uncited Author. “Timeline of Victor Hugo”. Website: BBC. Retrieved November 2005.

Uncited Author. (2000-2005). “Victor Hugo”. Website: The Literature Network. Retrieved November 2005.

Uncited Author. "Hugo Caricature". Website: Présence de la Littérature a l’école. Retrieved November 2005.

Further reading

Barbou, Alfred (1882). Victor Hugo and His Times. University Press of the Pacific: 2001 paper back edition..

Brombert, Victor H. (1984). Victor Hugo and the Visionary Novel. Boston: Harvard University Press..

Davidson, A.F. (1912). Victor Hugo: His Life and Work. University Press of the Pacific: 2003 paperback edition..

Dow, Leslie Smith (1993). Adele Hugo: La Miserable. Fredericton: Goose Lane Editions..

Falkayn, David (2001). Guide to the Life, Times, and Works of Victor Hugo. University Press of the Pacific..

Feller, Martin, Der Dichter in der Politik. Victor Hugo und der deutsch-französische Krieg von 1870/71. Untersuchungen zum französischen Deutschlandbild und zu Hugos Rezeption in Deutschland. Doctoral Dissertation, Marburg 1988.

Frey, John Andrew (1999). A Victor Hugo Encyclopedia. Greenwood Press..

Grant, Elliot (1946). The Career of Victor Hugo. Harvard University Press. Out of print.

Halsall, A.W. et al (1998). Victor Hugo and the Romantic Drama. University of Toronto Press..

Hart, Simon Allen (2004). Lady in the Shadows: The Life and Times of Julie Drouet, Mistress, Companion and Muse to Victor Hugo. Publish American..

Houston, John Porter (1975). Victor Hugo. New York: Twayne Publishers..

Ireson, J.C. (1997). Victor Hugo: A Companion to His Poetry. Clarendon Press..

Laster, Arnaud (2002). Hugo à l'Opéra. Paris: L'Avant-Scène Opéra, no. 208.

Maurois, Andre (1956). Olympio: The Life of Victor Hugo. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Maurois, Andre (1966). Victor Hugo and His World. London: Thames and Hudson. Out of print.

Robb, Graham (1997). Victor Hugo: A Biography. W.W. Norton & Company: 1999 paperback edition..(description/reviews)

Tonazzi, Pascal (2007) Florilège de Notre-Dame de Paris (anthologie) Paris, Editions Arléa ISBN 2869597959