| 姓: | sū | ||||||||||||

| 名: | dōng pō | ||||||||||||

| 字: | zǐ zhān | ||||||||||||

| 网笔号: | dōng pō jū shì | ||||||||||||

| 籍贯: | hé běi luán chéng | ||||||||||||

| 今属: | sì chuān shěng méi shān shì | ||||||||||||

| 出生地: | méi zhōu méi shān | ||||||||||||

| 去世地: | liǎng zhè lù cháng zhōu | ||||||||||||

| 陵墓: | hé nán jiá xiàn | ||||||||||||

阅读sū shì Su Shi在百家争鸣的作品!!! 阅读sū shì Su Shi在诗海的作品!!! | |||||||||||||

苏轼(1037年1月8日-1101年8月24日),眉州眉山(今四川省眉山市)人,北宋时著名的文学家、政治家、艺术家、医学家。字子瞻,一字和仲,号东坡居士、铁冠道人。嘉佑二年进士,累官至端明殿学士兼翰林学士,礼部尚书。南宋理学方炽时,加赐谥号文忠,复追赠太师。有《东坡先生大全集》及《东坡乐府》词集传世,宋人王宗稷收其作品,编有《苏文忠公全集》。

其散文、诗、词、赋均有成就,且善书法和绘画,是文学艺术史上的通才,也是公认韵文散文造诣皆比较杰出的大家。苏轼的散文为唐宋四家(韩柳欧苏)之末,与唐代的古文运动发起者韩愈并称为“韩潮苏海”,也与欧阳修并称“欧苏”;更与父亲苏洵、弟苏辙合称“三苏”,父子三人,同列唐宋八大家。苏轼之诗与黄庭坚并称“苏黄”,又与陆游并称“苏陆”;其词“以诗入词”,首开词坛“豪放”一派,振作了晚唐、五代以来绮靡的西昆体余风。后世与南宋辛弃疾并称“苏辛”,惟苏轼故作豪放,其实清朗;其赋亦颇有名气,最知名者为贬谪期间借题发挥写的前后《赤壁赋》。宋代每逢科考常出现其文命题之考试,故当时学者曰:“苏文熟,吃羊肉、苏文生,嚼菜羹”。艺术方面,书法名列“苏、黄、米、蔡”北宋四大书法家(宋四家)之首;其画则开创了湖州画派;并在题画文学史上占有举足轻重的地位。

政治上,在王安石变法期间,虽赞同政治应该改革,但反对王安石任用的后任吕惠卿及一些政策,招来新党爪牙李定横加陷害;后来又因反对“尽废新法”受到司马光为首的旧党斥退,终生当不了宰相。在新旧党争中两边不讨好导致仕途失意,被侍妾王朝云戏称为“一肚皮不合时宜”。元祐更化中,一度官至尚书;宋哲宗绍圣复述又加贬谪至儋州(海南岛);徽宗即位,遇赦北归时病卒于常州。墓在河南郏县。

生平

家世

祖父苏序,表字仲先。祖母史氏。父苏洵,母程氏。宋仁宗景祐三年(1037年),苏轼生于眉州眉山(今四川省眉山市)。其父亲将他命名“轼”,意为车前的扶手,取其默默无闻却扶危救困,不可或缺之意。苏轼有一个弟弟苏辙,小他两岁(1039年出生),两兄弟从小到大一起读书游玩,后来也同一年中进士。

苏轼年幼时父亲出游在外,母亲将其养大,并教他读书,曾令其以范滂为榜样。苏轼生性放达,好交友。和其父苏洵、其弟苏辙并称“三苏”。

苏洵修编族谱,自称是初唐相国苏味道后裔。然而苏洵自己也承认苏味道的后人与自己的高祖之间世系不可考证,苏洵的高祖才是信史的上限。苏洵的寻根方法,在当时就有人不以为然。柳立言认为苏洵修撰族谱编写世系,将三百多年前的唐代宰相苏味道当做自己家族的始迁祖,是看中苏味道的知名度,苏洵编订族谱的目的是不问亲疏,团结苏姓人士,争取共享政治和社会资源,以虚构始祖来联宗。

仕途

嘉佑二年(1057年),苏轼才20岁,与弟弟苏辙一同进京参加会考,苏轼中进士第2名。当时主试官是欧阳脩,苏轼以一篇《刑赏忠厚之至论》的论文得到考官梅尧臣的青睐,并推荐给主试官欧阳修。欧阳修亦十分赞赏,原本欲拔擢为第一,但又怕该文为自己的门生曾巩所作,为了避嫌,列为第二。结果试卷拆封后才发现该文为苏轼所作,而取为第一的是曾巩,正是阴错阳差,弄巧成拙。[来源请求]到了礼部复试时,苏轼再以《春秋对义》居曾巩之前,中乙科。

治平三年(1066年),父苏洵过世,苏轼回蜀守丧,英宗怜之,同意以官船载运苏轼一家。

熙宁二年(1069年),任祠部员外郎,反对王安石变法中的一些作为,王安石于是屡次在神宗面前诋毁苏轼,司马光、范镇举荐苏轼作谏官,王安石力反之,神宗想让苏轼写起居注,王安石向神宗进言,说苏轼在回家守丧时,乘机贩运苏木(一种染料),最后神宗放弃这个任命。三年,因为苏轼一直反对王安石,王安石门下的御史谢景温又诬陷苏轼贩卖私盐,范镇极辩苏轼贩盐之诬,并愿意退休负责。

熙宁三年(1070年),苏轼担任当年度的科举主考官,苏轼本欲拟上官均为第一名(状元),因发现上官均的策论有诋毁王安石变法的情况,便改上官均为第二名。

熙宁五年(1072年)苏轼因不堪新党的迫害,求外职,神宗本欲予以知州,但王安石只愿予之颍州通判,神宗最后折中,让苏轼担任比较好的杭州通判,三年之后升为知州,连知密州、徐州、湖州。熙宁十年四月,赴任徐州,是年七月七日,黄河决口,水困徐州,苏轼参加救灾。

元丰二年(1079年),四十三岁时,因乌台诗案入狱,几死,因为写文章向朝廷诀别,太皇太后曹氏、王安礼等人出面力挽,神宗动心,苏轼终免一死,贬谪为“检校尚书水部员外郎黄州团练副使本州安置”,为其文学创作生涯的重要阶段,而神宗亦爱其才,终得以保全,翌年被贬至黄州(今湖北省黄冈市),在黄州“深自闭塞,扁舟革履,放浪山水之间,与渔樵杂处”,与张怀民交游,也结交禅门人士,当时佛印担任庐山归宗寺住持,与苏轼时有往来。苏轼有〈戏答佛印偈〉曰:“百千灯作一灯光,尽是恒沙妙法王,是故东坡不敢借,借君四大作禅床。”元丰七年离开黄州。

元祐元年(1086年),宋哲宗即位,高太皇太后垂帘听政,回朝任礼部郎中、中书舍人、翰林学士,元祐四年(1089年)拜龙图阁学士,曾出知杭州、颍州等,官至礼部尚书。

元符三年(1100年),宋徽宗即位,向太后垂帘听政,下诏让苏轼北还。

建中靖国元年(1101年),夏天因冷饮过度,下痢不止,又误服黄芪,结果病情恶化,“齿间出血如蚯蚓者无数”,七月二十八日于常州孙氏馆病卒,享年六十四岁。由弟苏辙归葬于郏县小峨眉山。南宋宋孝宗追赠谥号“文忠”。

苏轼疲于应付新旧党争,遇事“如食内有蝇,吐之乃已”,苏轼既反对王安石比较急进的改革措施,也不同意旧党司马光尽废新法,所以虽然新党一直称苏轼为旧党,但其实他在新旧两党之间均受排斥,仕途坎坷,时常远贬外方,不过他在各地居官清正,为民兴利除弊,政绩颇善,口碑甚佳,杭州西湖的苏堤就是实证。

性格

好美食,创造许多饮食精品,好品茗,亦雅好游山林,黄庭坚称他“真神仙中人”。

风格

其文汪洋恣肆,明白畅达,曾自谓:“大略如行云流水,初无定质,但行于所当行,常止于所不可不止,虽嬉笑怒骂之辞,皆可书而诵之。”其诗清新豪健,善用夸张比喻。其体浑涵光芒,雄视百代,有文章以来,盖亦鲜矣。一时文人如黄庭坚、晁补之、秦观、张耒、陈师道,举世未之识,轼待之如朋俦,未尝以师资自予也。

黄州词,是苏词的奇观;黄州文,则是苏文的高峰;《赤壁赋》是其高峰之巅。黄庭坚曾批评苏轼说:“东坡文章妙天下,其短处在好骂,慎勿袭其轨也”。陈岩肖说:“坡为人慷慨疾恶,亦时见于诗,有古人规讽体”。陈师道说:“苏诗始学刘禹锡,故多怨刺,学不可不慎也”。

诗风

苏轼工诗,与黄庭坚合称“苏黄”。现存约二千七百多首,其诗内容广阔,风格多样,而以豪放为主。对后人影响最大的也是抒发人生感慨和歌咏自然景物的诗篇,表现出宋诗重理趣,好议论的特征。〈饮湖上初晴后雨〉写西湖之美:“水光潋滟晴方好,山色空濛雨亦奇。欲把西湖比西子,淡妆浓抹总相宜。”

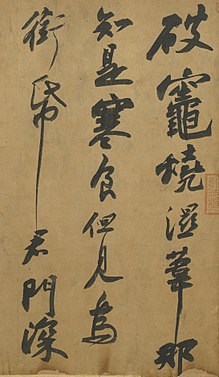

元丰四年暮春三月,东坡写下〈黄州寒食诗帖〉。此帖为两首五言古风,诗句沉郁苍劲,低回长叹,极富感染力。其书法不拘小节,字形章法布局俱佳,颇有右军遗意,唯用笔失之草率,在书法史上影响很大,二十世纪末更被誉为〈兰亭序〉、〈祭侄帖〉之后的“天下第三行书”。黄庭坚在此帖后题跋:“东坡此诗似李太白,犹恐太白有未到处。此书兼颜鲁公、杨少师、李西台笔意,试使东坡复为之,未必及此。它日东坡或见此书,应笑我于无佛处称尊也。”朱弁《曲洧旧闻》:“东坡文章至黄州以后,人莫能及,唯黄鲁直诗时可以抗衡;晚年过海,则鲁直亦瞠乎其后矣。”

白称诗仙,古体绝伦;杜诗律圣,拓宇七言;东坡晚出,各体皆能,无题不作,比配诗神。

词风

现存三百四十多首《念奴娇·赤壁怀古》、《水调歌头·明月几时有》、《定风波》传诵甚广。

苏轼扩大词的内容,抒情写景、说理怀古、感事等题材,无一不可入词。苏轼提高词的意境,扩大和开拓词境,提高格调,豪放词以外,也有清旷飘逸、空灵隽永、以至缠绵妩媚之作。

苏轼词风豪放(王国维曰“东坡之词旷”),将词“诗化”,笔力雄健,个性鲜明,展现出作者旷达、爽朗的个性,多豪情壮语,意气昂扬,感情奔放,想像丰富奇特。

体裁和音律上,苏轼不喜剪裁以就声律,词的文学生命重于音乐的生命。苏词作品往往有序,阐明词的内容,或作词的原委、时间、地点,事实分明。

相传苏轼官翰林学士时,曾问幕下士:“我词何如柳七(柳永)?”幕下士答曰:“柳郎中词只合十七八岁女郎,执红牙板,歌‘杨柳岸晓风残月’。学士词须关西大汉,铜琵琶、铁绰板,唱‘大江东去’。”

苏轼的词风被归类在“豪放派”,所以与周邦彦的“格律派”大相径庭。南宋时知名的词人辛弃疾也是豪放派的词人,后世将苏东坡与辛弃疾并称为“苏辛”。

赋风

书风

苏轼晚年用笔沉着,早期书法代表作为〈治平帖〉,笔触精到,字态妩媚。中年代表作为〈黄州寒食诗帖〉。此诗帖系元丰五年(1082年)苏轼因为乌台诗案遭贬黄州时所写诗两首。诗句沉郁苍凉又不失旷达,书法用笔、墨色也随着诗句语境的变化而变化,跌宕起伏,气势不凡而又一气呵成,不拘小节,率意为之,二十世纪末被誉为“天下第三行书”。晚年代表作有行书〈洞庭春色赋〉、〈中山松醪赋〉等,此二赋以古雅胜,姿态百出而结构紧密,集中反映了苏轼书法“结体短肥”的特点。其最晚的墨迹当是〈与谢民师论文帖〉(1100年)。

其代表作有〈黄州寒食诗帖〉、〈天际乌云帖〉、〈洞庭春色赋〉、〈中山松醪赋〉、〈春帖子词〉、〈爱酒诗〉、〈寒食诗〉、〈蜀中诗〉、〈人来得书帖〉、〈答谢民师论文帖〉、〈江上帖〉、〈李白仙诗帖〉、〈次韵秦太虚诗帖〉、〈渡海帖〉、〈祭黄几道文卷〉、〈梅花诗帖〉、〈前赤壁赋〉、〈东武帖〉、〈北游帖〉、〈新岁展庆帖〉、〈宝月帖〉、〈令子帖〉、〈致南圭使君帖〉、〈次辩才韵诗〉、〈一夜帖〉、〈宸奎阁碑〉、〈致若虚总管尺牍〉、〈怀素自序〉等。苏轼的书法,后人赞誉颇高。最有发言权的莫过于黄庭坚,他在《山谷集》里说,“本朝善书者,自当推(苏)为第一”。

画风

能画竹,学文同,也喜作枯木怪石。存世画迹有〈枯木怪石图卷〉、〈潇湘竹石图〉等。

著作

苏轼现存于世的文学著作共有2700多首诗,300多首词,以及大量散文作品。

最早的词则写于熙宁五年(1072年)。

存世书迹有〈答谢民师论文帖〉、〈祭黄几道文〉、〈前赤壁赋〉、〈黄州寒食诗帖〉、〈题西林壁〉、〈饮湖上初晴后雨〉等。

因南宋皇帝宋高宗、宋孝宗等对他其人其作的推崇,有宋一朝整理出版了《苏文忠公诗合注》《苏文忠公全集》等多部集作。《苏文忠公全集》又称《东坡全集》,传世的,至今所见,可分两大类。一类为分集编订,号称东坡七集本,亦标东坡全集,即东坡集四十卷,后集二十卷,奏议十五卷,内制集十卷,外制集三卷,和陶诗四卷,应诏集十卷,其出自苏轼原本原目,后人稍加增益,为之善本,风行海内;一类为分类合编,号称东坡大全集,《四库提要辨证》云:“分类合编者,疑即始于居世英本,宋时所谓大全集者类用此例,”又云:“宋时所刊大全集者,乃麻沙书坊所刻。”

家庭

| [显示]先祖 |

|---|

祖父:

父亲:

母亲:

兄弟姐妹:

苏洵与程氏共生有三男三女,然长子景先与三名女儿皆卒于程氏去世之前。虽然传说的“苏小妹三难新郎”故事中,苏东坡有个嫁与秦观的妹妹,但根据考证,苏东坡笔记著作中从未曾提到有妹妹,而且秦观在二十九岁并且已经娶妻之后,才初遇苏东坡,苏小妹应为虚构人物。

- 苏景先,早卒

- 苏氏,苏轼长姊,早卒

- 苏氏,苏轼次姊,早卒

- 苏八娘(1035年—1052年),苏轼三姊,十六岁嫁舅父程濬之子程之才,两年后被夫家虐待至死。清朝袁枚《随园诗话》误作苏轼之妹。

- 苏辙,苏轼之弟,唐宋八大家之一。

妻妾:

- 王弗,苏轼之妻,十六岁时与年方十九的苏轼成婚,婚后二人恩爱甜蜜。结婚十一年因病逝世,得年二十七。苏轼四十岁时曾作〈江城子·乙卯正月二十日夜记梦〉悼念亡妻。

- 王闰之,苏轼之妻,王弗堂妹,王弗逝去三年后嫁给苏轼。苏轼五十八岁时逝世,享年四十六。

- 王朝云,苏轼之妾,原为歌妓。三十八岁时的苏轼赎十二岁的朝云,后收为侍妾。陪伴苏轼度过仕途不顺的岁月。后卒于绍圣三年,享年三十四。

子女:

堂妹:

评价

古代

- 张戒:“自汉魏以来,诗妙于子建,成于李、杜,而坏于苏、黄。”(《岁寒堂诗话》卷上)

- 《宋史》:“苏轼自为童子时,士有传石介《庆历圣德诗》至蜀中者,轼历举诗中所言韩、富、杜、范诸贤以问其师。师怪而语之,则曰:“正欲识是诸人耳。”盖已有颉颃当世贤哲之意。弱冠,父子兄弟至京师,一日而声名赫然,动于四方。既而登上第,擢词科,入掌书命,出典方州。器识之闳伟,议论之卓荦,文章之雄隽,政事之精明,四者皆能以特立之志为之主,而以迈往之气辅之。故意之所向,言足以达其有猷,行足以遂其有为。至于祸患之来,节义足以固其有守,皆志与气所为也。仁宗初读轼、辙制策,退而喜曰:“朕今日为子孙得两宰相矣。”神宗尤爱其文,宫中读之,膳进忘食,称为天下奇才。二君皆有以知轼,而轼卒不得大用。一欧阳修先识之,其名遂与之齐,岂非轼之所长不可掩抑者,天下之至公也,相不相有命焉,呜呼!轼不得相,又岂非幸欤?或谓:“轼稍自韬戢,虽不获柄用,亦当免祸。”虽然,假令轼以是而易其所为,尚得为轼哉?”

- 宋仁宗:“吾今又为吾子孙得太平宰相两人。”

- 刘安世说:“东坡立朝大节极可观,才意高广,惟己之是信。”

- 黄庭坚:“人谓东坡作此文,因难以见巧,故极工。余则以为不然。彼其老于文章,故落笔皆超逸绝尘耳。”、给苏轼的挽联说:“文章妙天下,忠义贯日月。”、“真神仙中人。”

- 晁无咎:“苏东坡词,人谓多不谐音律。然居士词横放杰出,自是曲子中缚不住者。”

- 王直方:“东坡尝以所作小词示无咎、文潜,曰:‘何如少游?’二人皆对曰:‘少游诗似小词,先生小词似诗。’”

- 王灼:“东坡先生以文章馀事作诗,溢而作词曲,高处出神入天,平处尚临镜笑春,不顾侪辈。或曰:‘长短句中诗也。’为此论者,乃是遭柳永野狐涎之毒。诗与乐府同出,岂当分异?若从柳氏家法,正自不分异耳。东坡先生非心醉于音律者,偶尔作歌,指出向上一路,新天下耳目,弄笔者始知自振。今少年妄谓东坡移诗律作长短句,十有八九不学柳耆卿则学曹元宠,虽可笑,亦毋用笑也。”

- 宋孝宗:“忠言谠论,立朝大节,一时廷臣无出其右。”

- 陆游评苏:“世言东坡不能歌,故所作东府词多不协。晁以道谓:绍圣初,与东坡别于汴上,东坡酒酣,自歌〈古阳关〉。则公非不能歌,但豪放不喜剪裁以就声律耳。试取东坡诸词歌之,曲终,觉天风海雨逼人。”、“公不以一身祸福,易其忧国之心,千载之下,生气凛然。”

- 陈洵:“东坡独崇气格,箴规柳、秦,词体之尊,自东坡始。”

- 徐度:“(柳永)词虽极工致,然多杂以鄙语,故流俗人尤喜道之。其后欧、苏诸公继出,文格一变,至为歌词,体制高雅。”

- 胡寅:“词曲者,古乐府之末造也。文章豪放之士,鲜不寄意于此者,随亦自扫其迹,曰谑浪游戏而已也。唐人为之最工者。柳耆卿后出,掩众制而尽其妙。好之者以为不可复加。及眉山苏氏,一洗绮罗香泽之态,摆脱绸缪宛转之度,使人登高望远,举首高歌,而逸怀浩气,超然乎尘垢之外,于是花间为皂隶,而柳氏为舆台矣。”

- 王若虚:“是直以公为不及于情也。呜呼!风韵如东坡,而谓不及于情,可乎?彼高人逸士,正当如是。其溢为小词,而闲及于脂粉之间,所谓滑稽玩戏,聊复尔尔者也。若乃纤艳淫媟,入人骨髓,如田中行、柳耆卿辈,岂公之雅趣也哉?公雄文大手,乐府乃其游戏,顾岂于流俗争胜哉?盖其天资不凡,辞气迈往,故落笔皆绝尘耳。”

- 刘辰翁:“词至东坡,倾荡磊落,如诗,如文,如天地奇观。”

- 元好问:“唐歌词多宫体,又皆极力为之。自东坡一出,性情之外,不知有文字,真有“一洗万古凡马空”气象。虽时作宫体,亦岂可以宫体概之?人有言,乐府本不难作,从东坡放笔后便难作。此殆以工拙论,非知坡者。所以然者,诗三百所载小夫贱妇幽忧无聊赖之语,时猝为外物感触,满心而发,肆口而成者尔。其初果欲被管弦。谐金石,经圣人手,以与六经并传乎?小夫贱妇且然,而谓东坡翰墨游戏,乃求与前人角胜负,误矣。自今观之,东坡圣处,非有意于文字之为工,不得不然之为工也。坡以来,山谷、晁无咎、陈去非、辛幼安诸公,俱以歌词取称,吟咏性情,留连光景,清壮顿挫,能起人妙思。亦有语意拙直,不自缘饰,因病成妍者,皆自坡发之。”

- 王夫之:“扬雄、关朗、王弼、何晏、韩愈、苏轼之徒,日猖狂于天下,而张子韶、陆子静、王伯安窃浮屠之邪见,以乱圣学。为其徒者,弗妨以其耽酒嗜色,渔利赖宠之身,荡闲蔑耻,而自矜妙悟焉。呜呼,求明之害,尤烈于不明,亦至此哉!”

- 袁枚评苏诗:“有才而无情,多趣而少韵:由于天分高,学力浅也。有起而无结,多刚而少柔:验其知遇早晚景穷也。”

- 周济:“人赏东坡粗豪,吾赏东坡韶秀。韶秀是东坡佳处,粗豪则病也。东坡每事俱不十分用力,古文、书、画皆尔,词亦尔。”

- 刘熙载:“东坡词颇似老杜诗,以其无意不可入,无事不可言也。若其豪放之致,则时与太白为近。太白《忆秦娥》,声情悲壮。晚唐、五代,惟趋婉丽。至东坡始能复古。后世论词者,或转以东坡为变调,不知晚唐、五代乃变调也。东坡《定风波》云:‘尚余孤瘦雪霜姿。”《荷花媚》云:‘天然地,别是风流标格。’、‘雪霜姿’、‘风流标格’,学坡词者,便可从此领取。东坡词具神仙出世之姿,方外白玉蟾诸家,惜未诣此。”

- 曾国藩:“古人称立德、立功、立言为三不朽。立德最难,自周汉以后,罕见德传者。立功如萧、曹、房、杜、郭、李、韩、岳,立言如马、班、韩、欧、李、杜、苏、黄,古今曾有几人?”

- 蔡嵩云:“东坡词,胸有万卷,笔无点尘。其阔大处,不在能作豪放语,而在其襟怀有涵盖一切气象。若徒袭其外貌,何异东施效颦。东坡小令,清丽纡徐,雅人深致,另辟一境。设非胸襟高旷,焉能有此吐属。”

- 王鹏运:“北宋人词,如潘逍遥之超逸,宋子京之华贵,欧阳文忠之骚雅,柳屯田之广博,晏小山之疏俊,秦太虚之婉约,张子野之流丽,黄文节之隽上,贺方回之醇肆,皆可模拟得其仿佛。唯苏文忠之清雄,夐乎轶尘绝世,令人无从步趋。盖霄壤相悬,宁止才华而已?其性情,其学问,其襟抱,举非恒流所能梦见。词家苏辛并称,其实辛犹人境也,苏其殆仙乎!”

- 沈曾植:“东坡以诗为词,如雷大使之舞,虽极天下之工,要非本色。”此后山谈丛语也。然考蔡绦铁围山丛谈,称:‘上皇在位,时属升平。手艺之人有称者,棋则有刘仲甫、晋士明,琴则有僧梵如、僧全雅,教坊琵琶则有刘继安,舞有雷中庆,世皆呼之为雷大使,笛则孟水清。此数人者,视前代之技皆过之。’然则雷大使乃教坊绝技,谓非本色,将外方乐乃为本色乎?”

- 夏敬观:“东坡词如春花散空,不着迹象,使柳枝歌之,正如天风海涛之曲,中多幽咽怨断之音,此其上乘也。若夫激昂排宕、不可一世之概,陈无己所谓:‘如教坊雷大使之舞,虽极天下之工,要非本色。’乃其第二乘也。后之学苏者,惟能知第二乘,未有能达上乘者,即稼轩亦然。东坡《永遇乐》词云:‘????如三鼓,铿然一叶,黯黯梦云惊断。夜茫茫,重寻无处,觉来小园行遍。’此数语,可作东坡自道圣处。”

现代

- 钱穆说:“苏东坡诗之伟大,因他一辈子没有在政治上得意过。他一生奔走潦倒,波澜曲折都在诗里见。但苏东坡的儒学境界并不高,但在他处艰难的环境中,他的人格是伟大的,像他在黄州和后来在惠州、琼州的一段。那个时候诗都好,可是一安逸下来,就有些不行,诗境未免有时落俗套。东坡诗之长处,在有豪情,有逸趣。其恬静不如王摩诘,其忠恳不如杜工部。”、“他们(苏氏兄弟)的学术因罩上一层极厚的释老的色采,所以他们对于世务,认为并没有一种正面的、超出一切的理想标准。他们一面对世务却相当练达,凭他们活的聪明来随机应付。他们亦并不信有某一种制度,定比别一种制度好些。但他们的另一面,又爱好文章辞藻,所以他们持论,往往渲染过分,一说便说到尽量处。近于古代纵横的策士。”

- 方东树《昭昧詹言》云:“东坡……自以真骨面目与天下相见,随意吐属,自然高妙。”

- 1930年代,当林语堂尚在海外飘零之时,身边却时时携带笨重的苏轼文集,后来写下文词优美、脍炙人口[来源请求]的《苏东坡传》。当他在《苏东坡传》中提到为其作传的理由时,说:“像苏东坡这样富有创造力,这样守正不阿,这样放任不羁,这样令人万分倾倒而又望尘莫及的高士,有他的作品摆在书架上,就令人觉得有了丰富的精神食粮。现在我能专心致力写他这本传记,自然是一大乐事,此外还需要什么别的理由吗?”这正切中林语堂自己的赞叹:“苏东坡自有其迷人魔力。”、“苏东坡是一个无可救药的乐天派、一个伟大的人道主义者、一个百姓的朋友、一个大文豪、大书法家、创新的画家、造酒试验家、一个工程师、一个憎恨清教徒主义的人、一位瑜伽修行者佛教徒、巨儒政治家、一个皇帝的秘书、酒仙、厚道的法官、一位在政治上专唱反调的人。一个月夜徘徊者、一个诗人、一个小丑。但是这还不足以道出苏东坡的全部……苏东坡比中国其他的诗人更具有多面性天才的丰富感、变化感和幽默感,智能优异,心灵却像天真的小孩——这种混合等于耶稣所谓蛇的智慧加上鸽子的温文。”

- 王水照认为苏轼文学作品的数量之巨为北宋著名作家之冠,质量之优则为北宋“文学最高成就的杰出代表”。

- 2000年,法国《世界报》认为苏东坡的从政生涯与他的琴棋书画一样,都是人类的文化瑰宝,并且在专栏“千年人物”中,评选苏轼为唯一一位入选的中国人(共12位)。

- 2017/08/13,法国《世界报》副主编Jean-Pierre Langellier在第八届苏东坡文化节的演讲时,盛赞苏东坡的天才与人道精神。

注本

从宋代开始,苏轼作品的注本不断出现,较著名有:

- 诗注

- 文注

- 词注

轶闻

- 宋仁宗嘉佑二年,苏轼以一篇〈刑赏忠厚之至论〉的论文得到考官梅尧臣的青睐,并推荐给主试官欧阳修。欧阳修亦十分赞赏,欲拔擢为第一,但又怕该文为自己的门生曾巩所作,为了避嫌,列为第二。结果试卷拆封后才发现该文为苏轼所作。到了礼部复试时,苏轼再以〈春秋对义〉取为第一。

- 关于〈刑赏忠厚之至论〉中的内容:“皋陶曰杀之三,尧曰宥之三”,当时考官皆不知其典故,欧阳脩问苏轼出于何典。苏轼回答在《三国志·孔融传》中。欧阳脩翻查后仍找不到,苏轼答:“曹操灭袁绍,以绍子袁熙妻甄宓赐子曹丕。孔融云:‘即周武王伐纣以妲己赐周公’。操惊,问出于何典,融答:‘以今度之,想当然耳’。”欧阳脩听毕恍然大悟。

- 宋哲宗元祐元年(1086年)司马光去世,大臣们正举行明堂祭拜大典,赶不及奠祭,仪式一完成,大臣们希望赶去吊丧,程颐却拦住大家,说孔子“是日哭则不歌”,参加明堂典礼之后,不该又吊丧家。大家觉得这不近人情,反驳说,“哭则不歌”不代表“歌则不哭”。苏轼嘲笑程颐说:“这是枉死市上的叔孙通制订的礼法。”这是苏轼、程颐两人结怨的开始。

- 有一次国家忌日,众大臣到相国寺祷佛,程颐要求食素,苏轼责问说:“正叔(程颐表字),你不是不喜好佛教吗?为什么要吃素食?”程颐说:“礼法:守丧不可饮酒吃肉;忌日,是丧事的延续。”苏轼唱反调:“支持刘家的人露出左臂来罢!”(用史记典故,苏轼自比为汉朝的太尉周勃,把程颐比为吕氏乱党,要求大家支持他。)范淳夫等人吃素食,而秦观、黄庭坚等则吃肉。

- 苏轼很早接触佛教,一生与禅师交游颇广,在黄州时常与金山寺主持佛印禅师来往,一日苏轼做一首诗偈“稽首天中天,毫光照大千,八风吹不动,端坐紫金莲”呈给佛印。禅师即批“放屁”二字,嘱书童携回。东坡见后大怒,立即过江责问禅师,禅师大笑:“学士,学士,您不是‘八风吹不动’了吗,怎又一‘屁’就打过了江?”“八风吹不动”可见于《佛地经论》卷五,诗僧寒山诗歌亦有此句。

- 苏轼无论诗、词、文、赋、字、画,样样精到,常被认为乃是先人托化所致。广州西郊石门灵隐山上有宝陀院、妙高台,院住持得云和尚临终时,留信说三十年后他的忌日,当有贵人来访,可将遗书递上。到了元符三年(1100年)十月得云和尚三十周年忌日,苏轼正好游览来到宝陀院,觉得一切都很熟悉,阅毕住持遗书,有感而发题诗于妙高台壁上:

宝陀山上宝陀院,白发东坡喜再来。

前世得云今是我,依稀尤见妙高台。

- 苏轼本人是个美食家,性喜酒肉,肉中尤以猪肉为最爱,按周紫芝《竹坡诗话》:“东坡性喜食猪”。还有传说东坡肉和东坡酒相传均为苏轼发明。《曲洧旧闻》又记:苏东坡与客论食次,取纸一幅以示客云:“烂蒸同州羊羔,灌以杏酪香梗,荐以蒸子鹅,吴兴庖人斫松江鲙;既饱,以庐山玉帘泉,烹曾坑斗品茶。少焉解衣仰卧,使人诵东坡先生〈赤壁前后赋〉,亦足以一笑也。”

- 苏轼在〈与鞠持正书〉中写下:“文登虽稍远,百事可乐。岛中出一药,名曰:‘石芝’者,香味初嚼茶,久之甚美,闻甚益人!”。文中百事可乐意指凡事皆有乐趣,成为英语pepsi cola的音译。

参看

影视形象

| 演员 | 作品 | 年份 | 类型 |

| 唐国强 | 水浒传 | 1998 | 电视剧 |

| 魏骏杰 | 刁蛮娇妻苏小妹 | 2010 | 电视剧 |

| 陆毅 | 苏东坡 | 2012 | 电视剧 |

| 欧阳震华 | 东坡家事 | 2015 | 电视剧 |

| 郑则仕 | 风流才子苏东坡 | 2001 | 电视剧 |

纪录片

《苏东坡》,该片为中国央视所拍摄纪录片,2017入选中国优秀国产纪录片。

注释

- ^ 苏子瞻责黄州,居州之东坡,作雪堂,自号东坡居士,后人遂目子瞻为东坡。宋.朱彧《萍洲可谈》127页,中华书局

- ^ 晁说之《跋鲁直尝新柑帖》云:“元祐末有‘苏黄’之称。”(《嵩山文集》卷十八)

- ^ 赵翼《瓯北诗话》卷六称:“宋诗以苏陆为两大家”。

- ^ 一说“蔡”本指蔡京,后来因为蔡京人品不佳,被换成蔡襄。

- ^ 毛晋《苏米志林·是中何物》提到:“东坡一日退堂,食罢,扪腹徐行,顾谓侍儿曰:‘汝辈道我腹中何物?’一婢曰:‘都是文章。’坡不以为然。又一人曰:‘满腹都是机械。’坡亦未以为当。至朝云,乃曰:‘学士一肚皮不合时宜。’坡捧腹大笑。”此事又见曹臣编《舌华录》。

- ^ 《冷斋夜话》卷七“梦迎五祖戒禅师”引东坡语:“先妣方孕时梦一僧来托宿,记其颀然而眇一目。”张端义《贵耳集》卷上:“蜀有彭老山,东坡生则童,东坡死复青。”金人刘祁《归潜志》卷九则云:“昔东坡生,一夕眉山草木尽死。”

- ^ 苏洵《名二子》:“轮、辐、盖、轸,皆有职乎车。而轼独若无所为者。虽然,去轼,则吾未见其为完车也。轼乎,吾惧汝之不外饰也。天下之车莫不由辙,而言车之功,辙不与焉。虽然,车仆马毙,而患亦不及辙。是辙者,善处乎祸福之间也。辙乎,吾知免也矣!”

- ^ 《宋史·苏轼传》:“苏轼,字子瞻,眉州眉山人。生十年,父洵游学四方,母程氏亲授以书。程氏读东汉《范滂传》,慨然太息,轼请曰:“轼若为滂,母许之否乎?”程氏曰:“汝能为滂,吾顾不能为滂母邪?”

- ^ 《东坡事类》记载:“苏子瞻泛爱天下,士无贤不肖,欢如也。尝自言上可陪玉皇大帝,下可陪田院乞儿。子由晦默,少许可,尝诫子瞻择交,子瞻曰:‘吾眼前天下无一个不好的人。’”

- ^ 苏轼:笔秃千管,墨磨万锭. 人民网-文史频道. 2014-09-10 [2017-10-03].

- ^ 《宋代墓志铭的虚与实及其反映的历史变化:苏轼乳母任采莲墓志铭探微》, 《北京论坛(2005)文明的和谐与共同繁荣——全球化视野中亚洲的机遇与发展:“历史变化:实际的、被表现的和想象的”历史分论坛论文或摘要集(上)》2005年)》, 2014年: 47–50

- ^ 《答李端叔书》

- ^ 《东坡续集》卷六收录有双方的九封书信集。

- ^ 陆以湉《冷庐医话》:“建中靖国元年,公自海外归,年六十六,渡江至仪真,舣舟东海亭下,登金山妙高台时,公决意归毗陵,复同米元章游西山,逭暑南窗松竹下,时方酷暑,公久在海外,觉舟中热不可堪,夜辄露坐,复饮冷过度,中夜暴下,至旦惫甚,食黄粥觉稍适。会元章约明日为筵,俄瘴毒大作,暴下不止,自是胸膈作胀,却饮食,夜不能寐。……病暑饮冷暴下,不宜服黄芪,殆误服之。胸胀热雍,牙血泛滥,又不宜服人参、麦门冬。噫,此非为补药所误耶?”

- ^ 《曲洧旧闻》

- ^ 苏轼曾说:“吾侪新法之初,辄守偏见,至有异同之论。虽此心耿耿,归于忧国,而所言差谬,少有中理者。今圣德日新,众化大成,回视向之所执,益觉疏矣。若变志易守,以求进取,固所不敢;若哓哓不已,则忧患愈深。”(《东坡续集》卷4《与滕达道》)旧党专权后,苏轼批评司马光“专欲变熙宁之法,不复较量利害,参用所长。”(《东坡奏议集》卷3《辩试馆职策问札子》)

- ^ 苏轼的作品充斥着对食材的见解。贬黄州时,有诗《猪肉颂》:“黄州好猪肉,价钱等粪土。富者不肯吃,贫者不解煮。慢着火,少著水,火候足时它自美。每日起来打一碗,饱得自家君莫管。”苏轼亦有咏荔枝诗,《惠州一绝》:“罗浮山下四时春,卢橘杨梅次第新。日啖荔枝三百颗,不辞长做岭南人。”《河南邵氏闻见后录》记载苏轼嗜吃河豚。苏轼在儋州(海南岛)寄给其弟子由诗中还提到老鼠肉、蝙蝠肉,以及癞蛤蟆的滋味,诗云:“土人顿顿食薯芋,荐以熏鼠烧蝙蝠;旧闻蜜唧尝呕吐,稍近虾蟆缘习俗。”

- ^ 《观林诗话》载,苏轼喜欢凤翔玉女洞的泉水,每次去,都要取两瓶携回烹茶。

- ^ 《灵壁张氏园亭记》:“俯仰山林之下,予以养生冶性。”

- ^ 20.0 20.1 《题东坡字后》:“元祐中锁试礼部,每来见过,案上纸不择精粗,书遍乃已。性喜酒,然不能四五龠已烂醉,不辞谢而就卧,鼻酣如雷。少焉苏醒,落笔如风雨,虽谑弄皆有义味,真神仙中人。此岂与今世翰墨之士争衡哉!”(《豫章黄先生文集》卷二九)

- ^ 《答谢民师书》

- ^ 节录《宋史》卷三百三十八《苏轼传》

- ^ 《豫章黄先生文集》卷19《答洪驹父书》

- ^ 陈岩肖:《庚溪诗话》卷下

- ^ 陈师道:《后山诗话》

- ^ 孔凡礼的《三苏年谱》考察《苏轼诗集》、《苏轼文集》,确定苏轼现存诗2700多首,文4300多篇。

- ^ 孔凡礼的《三苏年谱》在薛瑞生等人著作的基础上,考察《全宋词》、《全宋词补辑》,说明苏轼现存词320多首。

- ^ 俞文豹《吹剑录》

- ^ °ê¥ß¬G®c³Õª«°. 国立故宫博物院网站:苏轼于元丰二年乙未(一○七九)被认为以诗讽刺时政(即乌台诗案),八月,被贬为黄州团练副使,次年二月抵任所,筑室于“东坡”,东坡之号即始于此。是以〈黄州寒食诗〉作于一○八二年。. Npm.gov.tw. [2017-06-04].

- ^ 30.0 30.1 王水照选注《苏轼选集》,上海古籍出版社,1984年2月第一版,ISBN 7-5325-0528-6。

- ^ 流传千年!苏东坡《木石图》真迹现世 拍卖估破15亿元. TVBS. 2018-08-30 [2018-08-31].

- ^ 胡波. 《东坡全集》版本考述. 四川图书馆学报. 2004, (2): 63.

- ^ 苏洵《祭亡妻文》:“有子六人,今谁在堂?惟轼与辙,仅存不亡。”

- ^ 欧阳修《苏明允墓志铭》:“生三子:曰景先,早卒;轼,今为殿中臣直史馆;辙,权大名府推官。三女皆早卒。”

- ^ 林语堂. 苏东坡传. 远景. 2008-10-31. ISBN 9789573907312.

- ^ 苏洵《自尤〈并叙〉》:“盖壬辰之岁而丧幼女,始将以尤其夫家,而卒以自尤也。女幼而好学,慷慨有过人之节,为文亦往往有可喜。既适其母之兄程浚之子之才,年十有八而死。而浚本儒者,然内行有所不谨,而其妻子尤好为无法。吾女介乎其间,因为其家之所不悦。适会其病,其夫与其舅姑遂不之视而急弃之,使至于死。始其死时,余怨之,虽尤吾之人亦不直浚。独余友发闻而深悲之,曰:‘夫彼何足尤者!子自知其贤,而不择以予人,咎则在子,而尚谁怨?’予闻其言而深悲之。其后八年,而予乃作自尤诗。”

- ^ 苏轼《乳母任氏墓志铭》:“乳亡姊八娘及轼。”

- ^ 袁枚《随园诗话》:“东坡止有二妹;一适柳,一适程也。今俗传为秦少游之妻,误矣!”

- ^ 《宋史·卷三百三十八·列传第九十七》

- ^ 见马永卿辑《元城语录》卷上

- ^ 《跋东坡<醉翁操>》

- ^ 黄庭坚《跋东坡墨迹》

- ^ 苏辙《亡兄子瞻端明墓志铭》

- ^ 《渔隐丛话》前集卷四十二引《王直方诗话》

- ^ 苏轼传记与集评

- ^ 《碧鸡漫志》卷二

- ^ 《宋史·列传第九十七》(卷三百三十八):“高宗即位,赠资政殿学士,以其孙符为礼部尚书。又以其文寘左右,读之终日忘倦,谓为文章之宗,亲制集赞,赐其曾孙峤。遂崇赠太师,谥文忠。轼三子:迈、迨、过,俱善为文。迈,驾部员外郎。迨,承务郎。”

- ^ 陆游《老学庵笔记》

- ^ 汲古阁本向子????《酒边词序》

- ^ 苏轼传记与集评

- ^ 元好问《遗山文集》卷三十六《新轩乐府引》

- ^ 王士祯《花草蒙拾》

- ^ 《介存斋论词杂著》

- ^ 苏轼传记与集评

- ^ 曾国藩文集

- ^ 王鹏运《半塘遗稿》

- ^ 苏轼传记与集评

- ^ 吷庵《手批东坡词》

- ^ 王国维《清真先生遗事·尚论三》

- ^ 钱穆《国史大纲》

- ^ 《苏东坡传·原序》,林语堂著,张振玉译

- ^ 衣若芬:为什么李白、杜甫不是“千年英雄”?. 联合早报网. 2018-01-06 [2018-02-22] (英语).

- ^ 东坡缘何成为千年英雄?让皮埃尔解密苏东坡有一颗自由的灵魂_眉山新闻_四川新闻_四川在线. sichuan.scol.com.cn.[2018-02-22].

- ^ 衣若芬:为什么李白、杜甫不是“千年英雄”?. 联合早报网. 2018-01-06 [2018-02-22] (英语).

- ^ 龚颐正《芥隐笔记·杀之三宥之三》

- ^ 《皇宋治迹统类》:“明堂降赦,臣僚称贺讫,两省官欲往奠司马光。程颐言:‘子于是日,哭则不歌。岂可贺赦才了,即往吊丧?’坐客有难之曰:‘孔子言哭则不歌,即不言歌则不哭。’苏轼遂戏程曰:‘此乃枉死市叔孙通所制礼也。’众皆大笑。结怨之端,盖自此始。”

- ^ 《程子微言》:“他日国忌,祷于相国寺,伊川令供素馔,子瞻诘之曰:‘正叔不好佛,胡为食素?’正叔曰:‘礼,居丧不饮酒食肉,忌日,丧之余也。’子瞻令具肉食,曰:‘为刘氏者左袒。’于是范淳夫辈食素,秦、黄辈食肉。”

- ^ 《栾城后集》卷二一《书白乐天集后二首》说他“少年知读佛书,习禅定。”

- ^ 宣化:《一屁蹦过江——苏东坡》,《宣化上人讲述》;台湾世新大学中文系教授黄启方指出“故事虽流传甚广,实乃子虚乌有”(《东坡和佛印》,载2010年4月21日《联合报》副刊)。

- ^ 《全唐诗》卷806

- ^ 翁方纲,《粤东金石略》

- ^ 词条名称:轼. 教育百科.

- ^ 词条名称:车辙. 教育百科.

- ^ 俞兆良、方丽萍. 苏东坡的酒肉人生与他的豁达情怀——以东坡酒和东坡肉为例. 乐山师范学院学报. 2016. doi:10.16069/j.cnki.51-1610/g4.2016.01.003.

- ^ 词条名称:百事可乐

- ^ 刘建维. 《苏东坡》入选2017年优秀国产纪录片 曾在黄冈多地取景拍摄_荆楚网. news.cnhubei.com. [2018-02-22]. (原始内容存档于2018-02-22).

参考书目

研究书目

- 林语堂著,宋碧云译:《苏东坡传》(台北:远景出版社,1979)。

- 保苅佳昭:《新兴与传统——苏轼词论述》(上海:上海古籍出版社,2005)。

- 内山精也著,朱刚等译:《传媒与真相——苏轼及其周围士大夫的文学》(上海:上海古籍出版社,2005)。

- 柳立言:〈苏轼乳母任采莲墓志铭所反映的历史变化〉。

- 叶嘉莹:〈论苏轼词〉。

- 浅见洋二:〈言论统制下的文学文本——以苏轼诗歌创作为中心〉。

- 浅见洋二:〈苏轼及杨万里诗中山水的拟人化〉。

- 内山精也:〈苏轼次韵词考——以诗词间所呈现的次韵之异同为中心〉。

- 东坡词酒意象探析,作者:许育乔,2008-02-22,国立台湾师范大学,机构典藏[永久失效链接]

- 东坡词梦意象的研究,作者:黄惠芳,2008-07-18,国立台湾师范大学

外部链接

Su Shi (Chinese: 蘇軾 / 苏轼;8 January 1037 – 24 August 1101), courtesy name Zizhan (Chinese: 子瞻), art name Dongpo (Chinese: 東坡), was a Chinese calligrapher, gastronome, painter, pharmacologist, poet, politician, and writer of the Song dynasty. A major personality of the Song era, Su was an important figure in Song Dynasty politics, aligning himself with Sima Guang and others, against the New Policy party led by Wang Anshi.

Su Shi is widely regarded as one of the most accomplished figures in classical Chinese literature, having produced some of the most well-known poems, lyrics, prose, and essays. Su Shi was famed as an essayist, and his prose writings lucidly contribute to the understanding of topics such as 11th-century Chinese travel literature or detailed information on the contemporary Chinese iron industry. His poetry has a long history of popularity and influence in China, Japan, and other areas in the near vicinity and is well known in the English-speaking parts of the world through the translations by Arthur Waley, among others. In terms of the arts, Su Shi has some claim to being "the pre-eminent personality of the eleventh century." Dongpo pork, a prominent dish in Hangzhou cuisine, is named in his honor.

Life

Su Shi was born in Meishan, near Mount Emei today Sichuan province. His brother Su Zhe and his father Su Xun were both famous literati. His given name, Shi (轼), refers to the crossbar railing at the front of a chariot; Su Xun felt that the railing was a humble, but indispensable, part of a carriage.

Su's early education was conducted under a Taoist priest at a local village school. Later his educated mother took over. Su married at the age of 17. Su and his younger brother (Zhe) had a close relationship, and in 1057, when Su was 19, he and his brother both passed the (highest-level) civil service examinations to attain the degree of jinshi, a prerequisite for high government office. His accomplishments at such a young age attracted the attention of Emperor Renzong, and also that of Ouyang Xiu, who became Su's patron thereafter. Ouyang had already been known as an admirer of Su Xun, sanctioning his literary style at court and stating that no other pleased him more. When the 1057 jinshi examinations were given, Ouyang Xiu required—without prior notice—that candidates were to write in the ancient prose style when answering questions on the Confucian classics. The Su brothers gained high honors for what were deemed impeccable answers and achieved celebrity status, especially in the case of Su Shi's exceptional performance in the subsequent 1061 decree examinations.

Beginning in 1060 and throughout the following twenty years, Su held a variety of government positions throughout China; most notably in Hangzhou, where he was responsible for constructing a pedestrian causeway across the West Lake that still bears his name: sudi (苏堤, 蘇堤, Su causeway). He had served as a magistrate in Mi Prefecture, which is located in modern-day Zhucheng County of Shandong province. Later, when he was governor of Xuzhou, he wrote a memorial to the throne in 1078 complaining about the troubling economic conditions and potential for armed rebellion in Liguo Industrial Prefecture, where a large part of the Chinese iron industry was located.

Su Shi was often at odds with a political faction headed by Wang Anshi. Su Shi once wrote a poem criticizing Wang Anshi's reforms, especially the government monopoly imposed on the salt industry. The dominance of the reformist faction at court allowed the New Policy Group greater ability to have Su Shi exiled for political crimes. The claim was that Su was criticizing the emperor, when in fact Su Shi's poetry was aimed at criticizing Wang's reforms. It should be said that Wang Anshi played no part in this action against Su, for he had retired from public life in 1076 and established a cordial relationship with Su Shi. Su Shi's first remote trip of exile (1080–1086) was to Huangzhou, Hubei. This post carried a nominal title, but no stipend, leaving Su in poverty. During this period, he began Buddhist meditation. With help from a friend, Su built a small residence on a parcel of land in 1081. Su Shi lived at a farm called Dongpo ('Eastern Slope'), from which he took his literary pseudonym. While banished to Hubei province, he grew fond of the area he lived in; many of the poems considered his best were written in this period. His most famous piece of calligraphy, Han Shi Tie, was also written there. In 1086, Su and all other banished statesmen were recalled to the capital due to the ascension of a new government. However, Su was banished a second time (1094–1100) to Huizhou (now in Guangdong province) and Hainan island. In 1098 the Dongpo Academy in Hainan was built on the site of the residence that he lived in whilst in exile.

Although political bickering and opposition usually split ministers of court into rivaling groups, there were moments of non-partisanship and cooperation from both sides. For example, although the prominent scientist and statesman Shen Kuo (1031–1095) was one of Wang Anshi's most trusted associates and political allies, Shen nonetheless befriended Su Shi. Su Shi was aware that it was Shen Kuo who, as regional inspector of Zhejiang, presented Su Shi's poetry to the court sometime between 1073 and 1075 with concern that it expressed abusive and hateful sentiments against the Song court. It was these poetry pieces that Li Ding and Shu Dan later utilized in order to instigate a law case against Su Shi, although until that point Su Shi did not think much of Shen Kuo's actions in bringing the poetry to light.

After a long period of political exile, Su received a pardon in 1100 and was posted to Chengdu. However, he died in Changzhou, Jiangsu province after his period of exile and while he was en route to his new assignment in the year 1101. Su Shi was 64 years old. After his death he gained even greater popularity, as people sought to collect his calligraphy, paintings depicting him, stone inscriptions marking his visit to numerous places, and built shrines in his honor. He was also depicted in artwork made posthumously, such as in Li Song's (1190–1225) painting of Su traveling in a boat, known as Su Dongpo at Red Cliff, after Su Song's poem written about a 3rd-century Chinese battle.

Family

Su Shi had three wives. His first wife was Wang Fu (王弗, 1039–1065), an astute, quiet lady from Sichuan who married him at the age of sixteen. She died 13 years later in 1065, on the second day of the fifth Chinese lunar month (Gregorian calendar June 14), after bearing him a son, Su Mai (蘇邁). Heartbroken, Su wrote a memorial for her (《亡妻王氏墓志銘》), stating Fu was not just a virtuous wife but advised him frequently on the integrity of his acquaintances when he was an official.

Ten years after the death of his first wife, Su composed a (ci) poem after dreaming of the deceased Fu in the night at Mi Prefecture. The poem, To the tune of 'Of Jinling' (江城子), remains one of the most famous poems Su wrote.

In 1068, two years after Wang Fu's death, Su married Wang Runzhi (王閏之, 1048–93), cousin of his first wife, and 11 years his junior. Wang Runzhi spent the next 15 years accompanying Su through his ups and downs in officialdom and political exile. Su praised Runzhi for being an understanding wife who treated his three sons equally (his eldest, Su Mai(苏迈,蘇邁), was born by Fu). Once, Su was angry with his young son for not understanding his unhappiness during his political exile. Wang chided Su for his silliness, prompting Su to write the domestic poem Young Son (《小兒》).

Wang Runzhi died in 1093, at forty-six, after bearing Su two sons, Su Dai (苏迨,蘇迨) and Su Guo (苏过,蘇過). Overcame with grief, Su expressed his wish to be buried with her in her memorial (see memorial 《祭亡妻同安郡君文》). On his second wife's second birthday after her death, Su wrote another ci poem, To the tune of 'Butterflies going after Flowers' (《蝶戀花》), for her.

Su's third wife, Wang Zhaoyun (王朝雲, 1062–1095) was his handmaiden who was a former Qiantang singing artiste. Wang was only about ten (eleven sui) when she became his personal slave. After she taught, herself to read though she was formerly illiterate. Zhaoyun was probably the most famous of Su's companions. Su's friend Qin Guan wrote a poem, A Gift for Dongpo's concubine Zhaoyun (《贈東坡妾朝雲》), praising her beauty and lovely voice. Su dedicated a number of his poems to Zhaoyun, like To the Tune of 'Song of the South’《南歌子》, Verses for Zhaoyun (《朝雲詩》), To the Tune of 'The Beauty Who asks One to Stay' (《殢人嬌·贈朝雲》), To the Tune of 'The Moon at Western Stream' 《西江月》. Zhaoyun remained a faithful companion to Su after Runzhi's death, but died of illness on 13 August 1095 (紹聖三年七月五日) at Huizhou. Zhaoyun bore Su a son, Su Dun (蘇遁) on 15 November 1083, who died in his infancy. After Zhaoyun's death, Su never married again.

Being a government official in a family of officials, Su was often separated from his loved ones depending on his posting. In 1078, he was serving as prefect of Suzhou. His beloved younger brother was able to join him for the mid-autumn festival, which inspired the poem "Mid-Autumn Moon" reflecting on the preciousness of time with family. It was written to be sung to the tune of "Yang Pass."

- As evening clouds withdraw a clear cool air floods in

- the jade wheel passes silently across the Silver River

- this life this night has rarely been kind

- where will we see this moon next year

- (translation by Red Pine)

Su Shi had three adult sons, the eldest son being Su Mai (蘇邁), who would also become a government official by 1084. Su Dai (蘇迨) and Su Guo (蘇過) are his other sons. When Su Shi died in 1101, his younger brother Su Zhe (蘇轍) buried him alongside second wife Wang Runzhi according to his wishes.

Work

Poetry

Around 2,700 of Su Song's poems have survived, along with 800 written letters. Su Dongpo excelled in the shi, ci and fu forms of poetry, as well as prose, calligraphy and painting. Some of his notable works include the First and Second Chibifu (赤壁賦 The Red Cliffs, written during his first exile), Nian Nu Jiao: Chibi Huai Gu (念奴嬌.赤壁懷古 Remembering Chibi, to the tune of Nian Nu Jiao) and Shui diao ge tou (水調歌頭 Remembering Su Zhe on the Mid-Autumn Festival, 中秋节,中秋節). The two former poems were inspired by the 3rd century naval battle of the Three Kingdoms era, the Battle of Chibi in the year 208. The bulk of his poems are in the shi style, but his poetic fame rests largely on his 350 ci style poems. Su Shi also founded the haofang school, which cultivated an attitude of heroic abandon. In both his written works and his visual art, he combined spontaneity, objectivity and vivid descriptions of natural phenomena. Su Shi wrote essays as well, many of which are on politics and governance, including his Liuhoulun (留侯論). His popular politically charged poetry was often the reason for the wrath of Wang Anshi's supporters towards him, culminating with the Crow Terrace Poetry Trial of 1079. He also wrote poems on Buddhist topics, including a poem later extensively commented on by Eihei Dōgen, the founder of the Japanese Sōtō school of Zen, in a chapter of his work Shōbōgenzō entitled The Sounds of Valley Streams, the Forms of Mountains.

Travel record literature

Su Shi also wrote of his travel experiences in 'daytrip essays', which belonged in part to the popular Song era literary category of 'travel record literature' (youji wenxue) that employed the use of narrative, diary, and prose styles of writing. Although other works in Chinese travel literature contained a wealth of cultural, geographical, topographical, and technical information, the central purpose of the daytrip essay was to use a setting and event in order to convey a philosophical or moral argument, which often employed persuasive writing. For example, Su Shi's daytrip essay known as Record of Stone Bell Mountain investigates and then judges whether or not ancient texts on 'stone bells' were factually accurate.

A memorial concerning the iron industry

While acting as Governor of Xuzhou, Su Shi in 1078 AD wrote a memorial to the imperial court about problems faced in the Liguo Industrial Prefecture which was under his watch and administration. In an interesting and revealing passage about the Chinese iron industry during the latter half of the 11th century, Su Shi wrote about the enormous size of the workforce employed in the iron industry, competing provinces that had rival iron manufacturers seeking favor from the central government, as well as the danger of rising local strongmen who had the capability of raiding the industry and threatening the government with effectively armed rebellion. It also becomes clear in reading the text that prefectural government officials in Su's time often had to negotiate with the central government in order to meet the demands of local conditions.

Technical issues of hydraulic engineering

During the ancient Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) of China, the sluice gate and canal lock of the flash lock had been known. By the 10th century the latter design was improved upon in China with the invention of the canal pound lock, allowing different adjusted levels of water along separated and gated segments of a canal. This innovation allowed for larger transport barges to pass safely without danger of wrecking upon the embankments, and was an innovation praised by those such as Shen Kuo (1031–1095). Shen also wrote in his Dream Pool Essays of the year 1088 that, if properly used, sluice gates positioned along irrigation canals were most effective in depositing silt for fertilization. Writing earlier in his Dongpo Zhilin of 1060, Su Shi came to a different conclusion, writing that the Chinese of a few centuries past had perfected this method and noted that it was ineffective in use by his own time.

Although Su Shi made no note of it in his writing, the root of this problem was merely the needs of agriculture and transportation conflicting with one another.

Gastronome

Su is called one of the four classical gastronomes. The other three are Ni Zan (1301–74), Xu Wei (1521–93), and Yuan Mei (1716–97). There is a legend, for which there is no evidence, that by accident he invented Dongpo pork, a famous dish in later centuries. Lin Hsiang Ju and Lin Tsuifeng in their scholarly Chinese Gastronomy give a recipe, "The Fragrance of Pork: Tungpo Pork", and remark that the "square of fat is named after Su Dongpo, the poet, for unknown reasons. Perhaps it is just because he would have liked it." A story runs that once Su Dongpo decided to make stewed pork. Then an old friend visited him in the middle of the cooking and challenged him to a game of Chinese chess. Su had totally forgotten the stew, which in the meantime had now become extremely thick-cooked, until its very fragrant smell reminded him of it.[citation needed]

Su, to explain his vegetarian inclinations, said that he never had been comfortable with killing animals for his dinner table, but had a craving for certain foods, such as clams, so he couldn't desist. When he was imprisoned his views changed. "Since my imprisonment I have not killed a single thing... having experienced such worry and danger myself, when I felt just like a fowl waiting in the kitchen, I can no longer bear to cause any living creature to suffer immeasurable fright and pain simply to please my palate."

See also

- Chinese literature

- Chinese poetry

- Classical Chinese poetry

- Crow Terrace Poetry Trial

- Culture of the Song Dynasty

- History of the Song Dynasty

- Shen Kuo

- Song poetry

- Tao Yuanming

- Su Shi's destiny quote

- Technology of the Song Dynasty

- Wang Shen

Notes

- ^ 《献曲求诗》:元丰五年十二月十九日东坡生日,置酒赤壁矶下,踞高峰,酒酣,笛声起于江上。客有郭、尤二生,颇知音,谓坡曰:“笛声有新意,非俗工也。”使人问之,则进士李委闻坡生日,作南曲目《鹤南飞》以献。呼之使前,则青巾紫裘腰笛而已。既奏新曲,又快作数弄,嘹然有穿云石之声,坐客皆引满醉倒。委袖出嘉纸注一幅曰:“吾无求于公,得一绝句足矣。”坡笑而从之。

- ^ Murck (2000), p. 31.

- ^ a b Red Pine, Poems of the Masters, Copper Canyon Press, 2003.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ebrey, Cambridge Illustrated History of China, 140.

- ^ a b c Hymes, 61.

- ^ Wagner, 178

- ^ Hegel, 13

- ^ a b Ebrey, East Asia, 164.

- ^ a b Hegel, 14

- ^ a b Hartman, 22.

- ^ Dreaming of My Deceased Wife on the Night of the 20th Day of the First Month

- ^ "Su Shi's poetry at Chinapage.org". Archived from the originalon 28 July 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2007.

- ^ http://www.ihp.sinica.edu.tw/~twsung/song/thesis/th14.pdf

- ^ See Su Su's 悼朝雲詩

- ^ Hargett, 75.

- ^ Bielefeldt, Carl (2013), "Sound of the Stream, Form of the Mountain: Keisei Sanshoku" (PDF), Dharma Eye, Sotoshu Shumucho (31): 21–29

- ^ a b Hargett, 74.

- ^ Hargett, 67-73.

- ^ Hargett, 74–76

- ^ Wagner, 178–179

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 344-350.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 350-351.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 351-352.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 230-231.

- ^ a b Needham Volume 4, Part 3, 230.

- ^ Endymion Wilkinson, Chinese History: A Manual (Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, Rev. and enl., 2000): 634.

- ^ Hsiang-Ju Lin and Tsuifeng Lin, with a Foreword and Introduction by Lin Yutang, Chinese Gastronomy. New York,: Hastings House, 1969 ISBN 0-8038-1131-4. Various reprints, p 55.

- ^ Egan, Word, Image, and Deed, p. 52-53.

- ^ https://www.christies.com/auctions/sushi

Translations

- Watson, Burton (translator). Selected Poems of Su Tung-p'o (English only) (Copper Canyon Press, 1994)

- Xu Yuanchong (translator). Selected Poems of Su Shi. (Chinese with English translations). Hunan: Hunan People's Publishing House, 2007.

Bibliography

- Ebrey, Walthall, Palais (2006). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-618-13384-4.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43519-6 (hardback); ISBN 0-521-66991-X (paperback).

- Egan, Ronald. Word, Image, and Deed in the Life of Su Shi. Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard University Press, Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph Series, 1994. ISBN 0-674-95598-6.

- Fuller, Michael Anthony. The Road to East Slope: The Development of Su Shi's Poetic Voice. Stanford University Press, 1990. ISBN 0-8047-1587-4.

- Hargett, James M. "Some Preliminary Remarks on the Travel Records of the Song Dynasty (960-1279)," Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews (CLEAR) (July 1985): 67-93.

- Hartman, Charles. "Poetry and Politics in 1079: The Crow Terrace Poetry Case of Su Shih," Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews (CLEAR) (Volume 12, 1990): 15–44.

- Hatch, George. (1993) "Su Hsun's Pragmatic Statecraft" in Ordering the World : Approaches to State and Society in Sung Dynasty China, ed. Robert P. Hymes, 59–76. Berkeley: Berkeley University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07691-4.

- Hegel, Robert E. "The Sights and Sounds of Red Cliffs: On Reading Su Shi," Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews (CLEAR) (Volume 20 1998): 11-30.

- Lin, Yutang. The Gay Genius: The Life and Times of Su Tungpo. J. Day Co., 1947. ISBN 0-8371-4715-8.

- Murck, Alfreda (2000). Poetry and Painting in Song China: The Subtle Art of Dissent. Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-00782-6.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 1, Introductory Orientations. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Sivin, Nathan (1995). "Shen Kua." In Sivin's Science in Ancient China: Researches and Reflections, text III: 1-53. Haldershot (Hampshire, England), and Burlington (Vermont, USA): VARIORUM, Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0-86078-492-4.

- Wagner, Donald B. "The Administration of the Iron Industry in Eleventh-Century China," Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient (Volume 44 2001): 175-197.

- Yang, Vincent. Nature and Self: A Study of the Poetry of Su Dongpo, With Comparisons to the Poetry of William Wordsworth (American University Studies, Series III). Peter Lang Pub Inc, 1989. ISBN 0-8204-0939-1.

Further reading

- Jacques, Rob. Adagio for Su Tung-p'o: Poems on How Consciousness Uses Flesh to Float through Space/Time. (Fernwood Press, 2019) ISBN 978-1-59498-065-7. Using lines from Su Tung-p'o's poems as epigraphs, Jacques explores the 11th Century Chinese poet's metaphysical views on life, love and eternity from a 21st Century perspective.

- Wang, Yugen. "The Limits of Poetry as Means of Social Criticism: The 1079 Literary Inquisition against Su Shi Revisited." Journal of Song-Yuan Studies. Volume 41, 2011. pp. 29–65. 10.1353/sys.2011.0028. Available at Project MUSE.

External links

- Su Shi and his Calligraphy Gallery at China Online Museum

- Works by or about Su Shi at Internet Archive

- Works by Su Shi at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Su Shi: Poems

- Poems by Su Shi

- Su Shi Poems in English