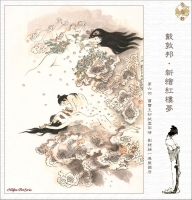

中国经典 》 紅樓夢 A Dream of Red Mansions 》

第六 賈寶玉初試雨情 劉姥姥一進榮國府 CHAPTER VI.

曹雪芹 Cao Xueqin

高鶚 Gao E

CHAPTER VI.

第六回 贾宝玉初试云雨情 刘姥姥一进荣国府 第六回 贾宝玉初试云雨情 刘姥姥一进荣国府

襲人忙趁衆奶娘丫鬟不在旁時,另取出一件中衣來與寶玉換上。寶玉含羞央告道:“好姐姐,萬告訴人。”襲人亦含羞笑問道:“你夢見什麽故事?是那流出來的那些東西?"寶玉道:“一言難。”說着便把夢中之事細說與襲人聽。然說至警幻所授雨之情,羞的襲人掩伏身而笑。寶玉亦素喜襲人柔媚嬌俏,遂強襲人同領警幻所訓雨之事。襲人素知賈母已將自己與寶玉的,今便如此,亦不為越禮,遂和寶玉偷試一番,幸得無人撞見。自此寶玉視襲人更比個不同,襲人待寶玉更為心。暫且無話說。

按榮府中一宅人算起來,人口雖不多,從上至下也有三四百丁,雖事不多,一天也有一二十件,竟如亂麻一般,並無個頭緒可作綱領。正尋思從那一件事自那一個人寫起方妙,恰好忽從鄰里里程之外,芥щ之微,小小一個人,因與榮府略有些瓜葛,這日正往榮府中來,因此便就此一說來,倒還是頭緒。你道這一姓甚名誰,又與榮府有甚瓜葛?且聽細講。方纔所說的這小小之,乃本地人氏,姓王,祖上曾作過小小的一個京官,昔年與鳳姐之祖王夫人之父認識。因貪王的勢利,便連宗認作侄兒。那時衹有王夫人之大兄鳳姐之父與王夫人隨在京中的,知有此一門連宗之族,者皆不認識。目今其祖已故,衹有一個兒子,名喚王成,因業蕭條,仍搬出城外原鄉中住去。王成新近亦因病故,衹有其子,小名狗兒。狗兒亦生一子,小名兒,嫡妻劉氏,又生一女,名喚青兒。一四口,仍以務農為業。因狗兒白日間又作些生計,劉氏又操井臼等事,青姊妹兩個無人看管,狗兒遂將嶽母劉姥姥接來一處過活。這劉姥姥乃是個積年的老寡婦,膝下又無兒女,靠兩畝薄田度日。今者女婿接來養活,豈不願意,遂一心一計,幫趁着女兒女婿過活起來。因這年盡弃盡力鼕初,天氣冷將上來,中鼕事未辦,狗兒未免心中煩慮,吃茶几杯悶酒,在閑尋氣惱,劉氏也不敢頂撞。因此劉姥姥看不過,乃勸道:“姑爺,你嗔着我多嘴。咱們村莊人,那一個不是老老誠誠的,守多大碗兒吃多大的飯。你皆因年小的時候,托着你那老之福,吃喝慣,如今所以把持不住。有錢就顧頭不顧尾,沒錢就瞎生氣,成個什麽男子漢大丈夫呢!如今咱們雖離城住着,終是天子腳下。這長安城中,遍地都是錢,可惜沒人會去拿去罷。在跳蹋會子也不中用。”狗兒聽說,便急道:“你老會炕頭兒上混說,難道叫我打劫偷去不成?"劉姥姥道:“誰叫你偷去呢。也到底想法兒大裁度,不然那銀子錢自己跑到咱來不成?"狗兒冷笑道:“有法兒還等到這會子呢。我又沒有收稅的親戚,作官的朋友,有什麽法子可想的?便有,也怕他們未必來理我們呢!”

劉姥姥道:“這倒不然。謀事在人,成事在天。咱們謀到,看菩薩的保佑,有些機會,也未可知。我倒替你們想出一個機會來。當日你們原是和金陵王連過宗的,二十年前,他們看承你們還好,如今自然是你們拉硬屎,不肯去親近他,故疏遠起來。想當初我和女兒還去過一遭。他們的二小姐着實響快,會待人,倒不拿大。如今現是榮國府賈二老爺的夫人。聽得說,如今上年紀,越憐貧恤老,最愛齋僧敬道,米錢的。如今王府雖升邊任,怕這二姑太太還認得咱們。你何不去走動走動,或者他念舊,有些好處,也未可知。要是他一點好心,拔一根寒毛比咱們的腰還粗呢。”劉氏一旁接口道:“你老雖說的是,但你我這樣個嘴臉,怎樣好到他門上去的。先不先,他們那些門上的人也未必肯去通信。沒的去打嘴現世。”

誰知狗兒利名心最重,聽如此一說,心下便有些活動起來。又聽他妻子這話,便笑接道:“姥姥既如此說,況且當年你又見過這姑太太一次,何不你老人明日就走一趟,先試試風頭再說。”劉姥姥道:“噯喲喲!可是說的,‘侯門深似海’,我是個什麽東西,他人又不認得我,我去也是白去的。”狗兒笑道:“不妨,我教你老人一個法子:你竟帶外孫子兒,先去找陪房周瑞,若見他,就有些意思。這周瑞先時曾和我父親交過一件事,我們極好的。”劉姥姥道:“我也知道他的。是許多時不走動,知道他如今是怎樣。這也說不得,你又是個男人,又這樣個嘴臉,自然去不得,我們姑娘年輕媳婦子,也難賣頭賣腳的,倒還是着我這付老臉去碰一碰。果然有些好處,大都有益,便是沒銀子來,我也到那公府侯門見一見世面,也不枉我一生。”說畢,大笑一。當晚計議已定。

次日天未明,劉姥姥便起來梳洗,又將兒教訓茶几句。那兒五六歲的孩子,一無所知,聽見劉姥姥帶他進城逛去,便喜的無不應承。於是劉姥姥帶他進城,找至寧榮街。來至榮府大門石獅子前,見簇簇轎馬,劉姥姥便不敢過去,且撣撣衣服,又教木板兒句話,然蹭到角門前。見幾個挺胸疊肚指手畫腳的人,坐在大凳上,說東談西呢。劉姥姥得蹭上來問:“太爺們納福。”衆人打量他一會,便問"那來的?"劉姥姥陪笑道:“我找太太的陪房周大爺的,煩那位太爺替我請他老出來。”那些人聽,都不瞅睬,半日方說道:“你遠遠的在那墻角下等着,一會子他們有人就出來的。”內中有一老年人說道:“不要誤他的事,何苦耍他。”因劉姥姥道:“那周大爺已往南邊去。他在一帶住着,他娘子卻在。你要找時,從這邊繞到街上門上去問就是。”

劉姥姥聽謝過,遂攜木板兒,繞到門上。見門前歇着些生意擔子,也有賣吃的,也有賣頑耍物件的,鬧吵吵三二十個小孩子在那廝鬧。劉姥姥便拉住一個道:“我問哥兒一聲,有個周大娘可在麽?"孩子們道:“那個周大娘?我們這裏周大娘有三個呢,還有兩個周奶奶,不知是那一行當的?"劉姥姥道:“是太太的陪房周瑞。”孩子道:“這個容易,你跟我來。”說着,跳躥躥的引着劉姥姥進皇后門,至一院墻邊,指與劉姥姥道:“這就是他。”又叫道:“周大娘,有個老奶奶來找你呢,我帶來。”

周瑞的在內聽說,忙迎出來,問:“是那位?"劉姥姥忙迎上來問道:“好呀,周嫂子!"周瑞的認半日,方笑道:“劉姥姥,你好呀!你說說,能年,我就忘。請鄰里里程來坐罷。”劉姥姥一壁走着,一壁笑說道:“你老是貴人多忘事,那還記得我們呢。”說着,來至房中。周瑞的命雇的小丫頭倒上茶來吃着。周瑞的又問兒道:“你都長這們大!"又問些皇后閑話。又問劉姥姥:“今日還是路過,還是特來的?"劉姥姥便說:“原是特來瞧瞧嫂子你,二則也請請姑太太的安。若可以領我見一見更好,若不能,便重嫂子轉致意罷。”

周瑞的聽,便已猜着分來意。因昔年他丈夫周瑞爭買田地一事,其中多得狗兒之力,今見劉姥姥如此而來,心中難卻其意,二則也要顯弄自己的當面表面反面方面正面迎面滿面封面地面路面世面平面斜面前面下面四面十面一面洗心革面方方面面面貌面容面色面目面面俱到。聽如此說,便笑說道:“姥姥你放心。大遠的誠心誠意來,豈有個不教你見個真佛去的呢。論理,人來客至話,卻不與我相。我們這裏都是各占一樣兒:我們男的管春兩季地租子,閑時帶着小爺們出門子就完,我管跟太太奶奶們出門的事。皆因你原是太太的親戚,又拿我當個人,投奔我來,我就破個例,給你通個信去。但一件,姥姥有所不知,我們這裏又不比五年前。如今太太竟不大管事*,都是璉二奶奶管受不了。你道這璉二奶奶是誰?就是太太的內侄女,當日大舅老爺的女兒,小名鳳哥的。”劉姥姥聽,罕問道:“原來是他!怪道呢,我當日就說他不錯呢。這等說來,我今兒還得見他。”周瑞的道:“這自然的。如今太太事多心煩,有客來,略可推得去的就推過去,都是鳳姑娘周旋迎待。今兒寧可不會太太,倒要見他一面,不枉這裏來一遭。”劉姥姥道:“阿彌陀佛!全仗嫂子方便。”周瑞的道:“說那話。俗語說的:‘與人方便,自己方便。’不過用我說一句話罷,害着我什麽。”說着,便叫小丫頭到倒廳上悄悄的打聽打聽,老太太屋受不了飯沒有。小丫頭去。這裏二人又說些閑話。

劉姥姥因說:“這鳳姑娘今年大還不過二十歲罷,就這等有本事,當這樣的,可是難得的。”周瑞的聽道:“我的姥姥,告訴不得你呢。這位鳳姑娘年紀雖小,行事卻比世人都大呢。如今出挑的美人一樣的模樣兒,少說些有一萬個心眼子。再要賭口齒,十個會說話的男人也說他不過。來你見就信。就一件,待下人未免太嚴些個。”說着,見小丫頭來說:“老太太屋已完飯,二奶奶在太太屋呢。”周瑞的聽,連忙起身,催着劉姥姥說:“快走,快走。這一下來他吃飯是個空子,咱們先趕着去。若遲一步,事的人也多,難說話。再歇中覺,越沒時候。”說着一齊下炕,打掃打掃衣服,又教木板兒句話,隨着周瑞的,逶迤往賈璉的住處來。先到倒廳,周瑞的將劉姥姥安插在那略等一等。自己先過影壁,進院門,知鳳姐未下來,先找着鳳姐的一個心腹通房大丫頭名喚平兒的。周瑞的先將劉姥姥起初來說明,又說:“今日大遠的特來請安。當日太太是常會的,今日不可不見,所以我帶他進來。等奶奶下來,我細細明,奶奶想也不責備我莽撞的。”平兒聽,便作主意:“叫他們進來,先在這裏坐着就是。”周瑞的聽,方出去引他兩個進入院來。上正房磯,小丫頭打起猩紅氈,入堂屋,聞一陣香撲臉來,竟不辨是何氣味,身子如在端一般。滿屋中之物都耀眼爭光的,使人頭懸目眩。劉姥姥此時惟點頭咂嘴念佛而已。於是來至東邊這間屋內,乃是賈璉的女兒大姐兒睡覺之所。平兒站在炕沿邊,打量劉姥姥兩眼,得問個好讓坐。劉姥姥見平兒遍身綾羅,插金帶銀,花容玉貌的,便當是鳳姐兒。要稱姑奶奶,忽見周瑞的稱他是平姑娘,又見平兒趕着周瑞的稱周大娘,方知不過是個有些當面表面反面方面正面迎面滿面封面地面路面世面平面斜面前面下面四面十面一面洗心革面方方面面面貌面容面色面目面面俱到的丫頭。於是讓劉姥姥和兒上炕,平兒和周瑞的對坐在炕沿上,小丫頭子斟茶來吃茶。

劉姥姥聽見咯當咯當的響聲,大有似乎打籮櫃篩的一般,不免東瞧西望的。忽見堂屋中柱子上挂着一個匣子,底下又墜着一個秤砣般一物,卻不住的亂幌。劉姥姥心中想着:“這是什麽愛物兒?有甚用呢?"正呆時,聽得當的一聲,又若金銅磬一般,不防倒唬的一展眼。接着又是一連八九下。方欲問時,見小丫頭子們齊亂跑,說:“奶奶下來。”周瑞的與平兒忙起身,命劉姥姥"管等着,是時候我們來請你。”說着,都迎出去。

劉姥姥屏聲側耳默候。聽遠遠有人笑聲,約有一二十婦人,衣裙ъл,漸入堂屋,往那邊屋內去。又見兩三個婦人,都捧着大漆捧盒,進這邊來等候。聽得那邊說聲"飯",漸漸的人才散出,衹有伺候端菜的幾個人。半日鴉雀不聞之,忽見二人擡一張炕桌來,放在這邊炕上,桌上碗盤森列,仍是滿滿的魚肉在內,不過略動茶几樣。兒一見,便吵着要肉吃,劉姥姥一巴掌打他去。忽見周瑞的笑嘻嘻走過來,招手兒叫他。劉姥姥會意,於是帶木板兒下炕,至堂屋中,周瑞的又和他唧咕一會,方過這邊屋來。

見門外鏨銅鈎上懸着大紅撒花軟,南窗下是炕,炕上大紅氈條,靠東邊壁立着一個鎖子錦靠背與一個引枕,鋪着金心緑閃緞大坐褥,旁邊有雕漆痰盒。那鳳姐兒常帶着木板貂鼠昭君套,圍着攢珠勒子,穿着桃紅撒花襖,石青刻絲灰鼠披風,大紅洋縐銀鼠皮裙,粉光脂豔,端端正正坐在那,手內拿着小銅火箸兒撥手爐內的灰。平兒站在炕沿邊,捧着小小的一個填漆茶盤,盤內一個小蓋。鳳姐也不接茶,也不擡頭,管撥手爐內的灰,慢慢的問道:“怎麽還不請進來?"一面說,一面擡身要茶時,見周瑞的已帶兩個人在地下站着呢。這忙欲起身,猶未起身時,滿面春風的問好,又嗔着周瑞的怎麽不早說。劉姥姥在地下已是拜數拜,問姑奶奶安。鳳姐忙說:“周姐姐,快攙起來,拜罷,請坐。我年輕,不大認得,可也不知是什麽輩數,不敢稱呼。”周瑞的忙道:“這就是我回族的那姥姥。”鳳姐點頭。劉姥姥已在炕沿上坐。兒便躲在背,百般的哄他出來作揖,他死也不肯。

鳳姐兒笑道:“親戚們不大走動,都疏遠。知道的呢,說你們棄厭我們,不肯常來,不知道的那起小人,還當我們眼沒人似的。”劉姥姥忙念佛道:“我們道艱難,走不起,來這裏,沒的給姑奶奶打嘴,就是管爺們看着也不象。”鳳姐兒笑道:“這話沒的叫人惡心。不過賴着祖父虛名,作窮官兒,誰有什麽,不過是個舊日的空架子。俗語說,‘朝廷還有三門子窮親戚’呢,何況你我。”說着,又問周瑞的受不了太太沒有。周瑞的道:“如今等奶奶的示下。”鳳姐道:“你去瞧瞧,要是有人有事就罷,得閑兒呢就,看怎麽說。”周瑞的答應着去。

這裏鳳姐叫人抓些果子與兒吃,剛問些閑話時,就有下許多媳婦管事的來話。平兒受不了,鳳姐道:“我這裏陪客呢,晚上再來。若有很要緊的,你就帶進來現辦。”平兒出去,一會進來說:“我都問,沒什麽緊事,我就叫他們散。”鳳姐點頭。見周瑞的來,鳳姐道:“太太說,今日不得閑,二奶奶陪着便是一樣。多謝費心想着。白來逛逛呢便罷,若有甚說的,管告訴二奶奶,都是一樣。”劉姥姥道:“也沒甚說的,不過是來瞧瞧姑太太,姑奶奶,也是親戚們的情分。”周瑞的道:“沒甚說的便罷,若有話,管二奶奶,是和太太一樣的。”一面說,一面遞眼色與劉姥姥。劉姥姥會意,未語先飛紅的臉,欲待不說,今日又所為何來?得忍恥說道:“論理今兒初次見姑奶奶,卻不該說,是大遠的奔你老這裏來,也少不的說。”剛說到這裏,聽二門上小廝們說:“東府的小大爺進來。”鳳姐忙止劉姥姥:“不必說。”一面便問:“你蓉大爺在那呢?"聽一路靴子腳響,進來一個十七八歲的少年,面目清秀,身材俊俏,輕裘寶帶,美服華冠。劉姥姥此時坐不是,立不是,藏沒處藏。鳳姐笑道:“你管坐着,這是我侄兒。”劉姥姥方扭扭捏捏在炕沿上坐。

賈蓉笑道:“我父親打我來求嬸子,說上老舅太太給嬸子的那架玻璃炕屏,明日請一個要緊的客,受不了略一就送過來。”鳳姐道:’說遲一日,昨兒已經給人。”賈蓉聽着,嘻嘻的笑着,在炕沿上半跪道:’嬸子若不,又說我不會說話,又挨一頓好打呢。嬸子當可憐侄兒罷。”鳳姐笑道:“也沒見你們,王的東西都是好的不成?你們那放着那些好東西,是看不見,偏我的就是好的。”賈蓉笑道:“那有這個好呢!求開恩罷。”鳳姐道:“若碰一點兒,你可仔細你的皮!"因命平兒拿樓房的鑰匙,傳幾個妥當人擡去。賈蓉喜的眉開眼笑,說:“我親自帶人拿去,由他們亂碰。”說着便起身出去。

這裏鳳姐忽又想起一事來,便窗外叫:“蓉哥來。”外茶几個人接聲說:“蓉大爺快來。”賈蓉忙身轉來,垂手侍立,聽何指示。那鳳姐管慢慢的吃茶,出半日的神,又笑道:“罷,你且去罷。晚飯你來再說罷。這會子有人,我也沒精神。”賈蓉應一聲,方慢慢的退去。

這裏劉姥姥心神方定,又說道:“今日我帶你侄兒來,也不為的,因他老子娘在鄰里里程,連吃的都沒有。如今天又冷,越想沒個派頭兒,得帶你侄兒奔你老來。”說着又推兒道:“你那爹在怎麽教你來?打咱們作煞事來?顧吃果子咧。”鳳姐早已明白,聽他不會說話,因笑止道:“不必說,我知道。”因問周瑞的:“這姥姥不知可用早飯沒有?"劉姥姥忙說道:“一早就往這裏趕咧,那還有吃飯的工夫咧。”鳳姐聽說,忙命快傳飯來。一時周瑞的傳一桌客飯來,在東邊屋內,過來帶劉姥姥和兒過去吃飯。鳳姐說道:“周姐姐,好生讓着些兒,我不能陪。”於是過東邊房來。又叫過周瑞的去,問他受不了太太,說些什麽?周瑞的道:“太太說,他們原不是一子,不過因出一姓,當年又與太老爺在一處作官,偶然連宗的。這年來也不大走動。當時他們來一遭,卻也沒空他們。今兒既來瞧瞧我們,是他的好意思,也不可簡慢他。便是有什麽說的,叫奶奶裁度着就是。”鳳姐聽說道:“我說呢,既是一子,我如何連影兒也不知道。”

說話時,劉姥姥已吃畢飯,拉木板兒過來,м舌咂嘴的道謝。鳳姐笑道:“且請坐下,聽我告訴你老人。方纔的意思,我已知道。若論親戚之間,原該不等上門來就該有照應是。但如今內雜事太煩,太太漸上年紀,一時想不到也是有的。況是我近來接着管些事,都不知道這些親戚們。二則外頭看着雖是烈烈轟轟的,殊不知大有大的艱難去處,說與人也未必信罷。今兒你既老遠的來,又是頭一次見我張口,怎好叫你空去呢。可巧昨兒太太給我的丫頭們做衣裳的二十兩銀子,我還沒動呢,你若不嫌少,就暫且先拿去罷。”

那劉姥姥先聽見告艱難,當是沒有,心便突突的,來聽見給他二十兩,喜的又渾身癢起來,說道:“噯,我也是知道艱難的。但俗語說的:‘瘦死的駱駝比馬大’,憑他怎樣,你老拔根寒毛比我們的腰還粗呢!"周瑞的見他說的粗鄙,管使眼色止他。鳳姐看見,笑而不睬,命平兒把昨兒那包銀子拿來,再拿一吊錢來,都送到劉姥姥的跟前。鳳姐乃道:“這是二十兩銀子,暫且給這孩子做件鼕衣罷。若不拿着,就真是怪我。這錢雇車坐罷。改日無事,管來逛逛,方是親戚們的意思。天也晚,也不虛留你們,到鄰里里程該問好的問個好兒罷。”一面說,一面就站起來。

劉姥姥管恩萬謝的,拿銀子錢,隨周瑞的來至外。周瑞的道:“我的娘啊!你見他怎麽倒不會說?開口就是‘你侄兒’。我說句不怕你惱的話,便是親侄兒,也要說和軟些。蓉大爺是他的正經侄兒呢,他怎麽又跑出這麽一個侄兒來。”劉姥姥笑道:“我的嫂子,我見他,心眼兒愛還愛不過來,那還說的上話來呢。”二人說着,又到周瑞坐片時。劉姥姥便要留下一塊銀子與周瑞孩子們買果子吃,周瑞的如何放在眼,執意不肯。劉姥姥感謝不,仍從門去。正是:

得意濃時易接濟,受恩深處親朋。

Chia Pao-yue reaps his first experience in licentious love. Old Goody Liu pays a visit to the Jung Kuo Mansion.

Mrs. Ch'in, to resume our narrative, upon hearing Pao-yue call her in his dream by her infant name, was at heart very exercised, but she did not however feel at liberty to make any minute inquiry.

Pao-yue was, at this time, in such a dazed state, as if he had lost something, and the servants promptly gave him a decoction of lungngan. After he had taken a few sips, he forthwith rose and tidied his clothes.

Hsi Jen put out her hand to fasten the band of his garment, and as soon as she did so, and it came in contact with his person, it felt so icy cold to the touch, covered as it was all over with perspiration, that she speedily withdrew her hand in utter surprise.

"What's the matter with you?" she exclaimed.

A blush suffused Pao-yue's face, and he took Hsi Jen's hand in a tight grip. Hsi Jen was a girl with all her wits about her; she was besides a couple of years older than Pao-yue and had recently come to know something of the world, so that at the sight of his state, she to a great extent readily accounted for the reason in her heart. From modest shame, she unconsciously became purple in the face, and not venturing to ask another question she continued adjusting his clothes. This task accomplished, she followed him over to old lady Chia's apartments; and after a hurry-scurry meal, they came back to this side, and Hsi Jen availed herself of the absence of the nurses and waiting-maids to hand Pao-yue another garment to change.

"Please, dear Hsi Jen, don't tell any one," entreated Pao-yue, with concealed shame.

"What did you dream of?" inquired Hsi Jen, smiling, as she tried to stifle her blushes, "and whence comes all this perspiration?"

"It's a long story," said Pao-yue, "which only a few words will not suffice to explain."

He accordingly recounted minutely, for her benefit, the subject of his dream. When he came to where the Fairy had explained to him the mysteries of love, Hsi Jen was overpowered with modesty and covered her face with her hands; and as she bent down, she gave way to a fit of laughter. Pao-yue had always been fond of Hsi Jen, on account of her gentleness, pretty looks and graceful and elegant manner, and he forthwith expounded to her all the mysteries he had been taught by the Fairy.

Hsi Jen was, of course, well aware that dowager lady Chia had given her over to Pao-yue, so that her present behaviour was likewise no transgression. And subsequently she secretly attempted with Pao-yue a violent flirtation, and lucky enough no one broke in upon them during their tete-a-tete. From this date, Pao-yue treated Hsi Jen with special regard, far more than he showed to the other girls, while Hsi Jen herself was still more demonstrative in her attentions to Pao-yue. But for a time we will make no further remark about them.

As regards the household of the Jung mansion, the inmates may, on adding up the total number, not have been found many; yet, counting the high as well as the low, there were three hundred persons and more. Their affairs may not have been very numerous, still there were, every day, ten and twenty matters to settle; in fact, the household resembled, in every way, ravelled hemp, devoid even of a clue-end, which could be used as an introduction.

Just as we were considering what matter and what person it would be best to begin writing of, by a lucky coincidence suddenly from a distance of a thousand li, a person small and insignificant as a grain of mustard seed happened, on account of her distant relationship with the Jung family, to come on this very day to the Jung mansion on a visit. We shall therefore readily commence by speaking of this family, as it after all affords an excellent clue for a beginning.

The surname of this mean and humble family was in point of fact Wang. They were natives of this district. Their ancestor had filled a minor office in the capital, and had, in years gone by, been acquainted with lady Feng's grandfather, that is madame Wang's father. Being covetous of the influence and affluence of the Wang family, he consequently joined ancestors with them, and was recognised by them as a nephew.

At that time, there were only madame Wang's eldest brother, that is lady Feng's father, and madame Wang herself, who knew anything of these distant relations, from the fact of having followed their parents to the capital. The rest of the family had one and all no idea about them.

This ancestor had, at this date, been dead long ago, leaving only one son called Wang Ch'eng. As the family estate was in a state of ruin, he once more moved outside the city walls and settled down in his native village. Wang Ch'eng also died soon after his father, leaving a son, known in his infancy as Kou Erh, who married a Miss Liu, by whom he had a son called by the infant name of Pan Erh, as well as a daughter, Ch'ing Erh. His family consisted of four, and he earned a living from farming.

As Kou Erh was always busy with something or other during the day and his wife, dame Liu, on the other hand, drew the water, pounded the rice and attended to all the other domestic concerns, the brother and sister, Ch'ing Erh and Pan Erh, the two of them, had no one to look after them. (Hence it was that) Kou Erh brought over his mother-in-law, old goody Liu, to live with them.

This goody Liu was an old widow, with a good deal of experience. She had besides no son round her knees, so that she was dependent for her maintenance on a couple of acres of poor land, with the result that when her son-in-law received her in his home, she naturally was ever willing to exert heart and mind to help her daughter and her son-in-law to earn their living.

This year, the autumn had come to an end, winter had commenced, and the weather had begun to be quite cold. No provision had been made in the household for the winter months, and Kou Erh was, inevitably, exceedingly exercised in his heart. Having had several cups of wine to dispel his distress, he sat at home and tried to seize upon every trifle to give vent to his displeasure. His wife had not the courage to force herself in his way, and hence goody Liu it was who encouraged him, as she could not bear to see the state of the domestic affairs.

"Don't pull me up for talking too much," she said; "but who of us country people isn't honest and open-hearted? As the size of the bowl we hold, so is the quantity of the rice we eat. In your young days, you were dependent on the support of your old father, so that eating and drinking became quite a habit with you; that's how, at the present time, your resources are quite uncertain; when you had money, you looked ahead, and didn't mind behind; and now that you have no money, you blindly fly into huffs. A fine fellow and a capital hero you have made! Living though we now be away from the capital, we are after all at the feet of the Emperor; this city of Ch'ang Ngan is strewn all over with money, but the pity is that there's no one able to go and fetch it away; and it's no use your staying at home and kicking your feet about."

"All you old lady know," rejoined Kou Erh, after he had heard what she had to say, "is to sit on the couch and talk trash! Is it likely you would have me go and play the robber?"

"Who tells you to become a robber?" asked goody Liu. "But it would be well, after all, that we should put our heads together and devise some means; for otherwise, is the money, pray, able of itself to run into our house?"

"Had there been a way," observed Kou Erh, smiling sarcastically, "would I have waited up to this moment? I have besides no revenue collectors as relatives, or friends in official positions; and what way could we devise? 'But even had I any, they wouldn't be likely, I fear, to pay any heed to such as ourselves!"

"That, too, doesn't follow," remarked goody Liu; "the planning of affairs rests with man, but the accomplishment of them rests with Heaven. After we have laid our plans, we may, who can say, by relying on the sustenance of the gods, find some favourable occasion. Leave it to me, I'll try and devise some lucky chance for you people! In years gone by, you joined ancestors with the Wang family of Chin Ling, and twenty years back, they treated you with consideration; but of late, you've been so high and mighty, and not condescended to go and bow to them, that an estrangement has arisen. I remember how in years gone by, I and my daughter paid them a visit. The second daughter of the family was really so pleasant and knew so well how to treat people with kindness, and without in fact any high airs! She's at present the wife of Mr. Chia, the second son of the Jung Kuo mansion; and I hear people say that now that she's advanced in years, she's still more considerate to the poor, regardful of the old, and very fond of preparing vegetable food for the bonzes and performing charitable deeds. The head of the Wang mansion has, it is true, been raised to some office on the frontier, but I hope that this lady Secunda will anyhow notice us. How is it then that you don't find your way as far as there; for she may possibly remember old times, and some good may, no one can say, come of it? I only wish that she would display some of her kind-heartedness, and pluck one hair from her person which would be, yea thicker than our waist."

"What you suggest, mother, is quite correct," interposed Mrs. Liu, Kou Erh's wife, who stood by and took up the conversation, "but with such mouth and phiz as yours and mine, how could we present ourselves before her door? Why I fear that the man at her gate won't also like to go and announce us! and we'd better not go and have our mouths slapped in public!"

Kou Erh, who would have thought it, prized highly both affluence and fame, so that when he heard these remarks, he forthwith began to feel at heart a little more at ease. When he furthermore heard what his wife had to say, he at once caught up the word as he smiled.

"Old mother," he rejoined; "since that be your idea, and what's more, you have in days gone by seen this lady on one occasion, why shouldn't you, old lady, start to-morrow on a visit to her and first ascertain how the wind blows!"

"Ai Ya!" exclaimed old Goody, "It may very well be said that the marquis' door is like the wide ocean! what sort of thing am I? why the servants of that family wouldn't even recognise me! even were I to go, it would be on a wild goose chase."

"No matter about that," observed Kou Erh; "I'll tell you a good way; you just take along with you, your grandson, little Pan Erh, and go first and call upon Chou Jui, who is attached to that household; and when once you've seen him, there will be some little chance. This Chou Jui, at one time, was connected with my father in some affair or other, and we were on excellent terms with him."

"That I too know," replied goody Liu, "but the thing is that you've had no dealings with him for so long, that who knows how he's disposed towards us now? this would be hard to say. Besides, you're a man, and with a mouth and phiz like that of yours, you couldn't, on any account, go on this errand. My daughter is a young woman, and she too couldn't very well go and expose herself to public gaze. But by my sacrificing this old face of mine, and by going and knocking it (against the wall) there may, after all, be some benefit and all of us might reap profit."

That very same evening, they laid their plans, and the next morning before the break of day, old goody Liu speedily got up, and having performed her toilette, she gave a few useful hints to Pan Erh; who, being a child of five or six years of age, was, when he heard that he was to be taken into the city, at once so delighted that there was nothing that he would not agree to.

Without further delay, goody Liu led off Pan Erh, and entered the city, and reaching the Ning Jung street, she came to the main entrance of the Jung mansion, where, next to the marble lions, were to be seen a crowd of chairs and horses. Goody Liu could not however muster the courage to go by, but having shaken her clothes, and said a few more seasonable words to Pan Erh, she subsequently squatted in front of the side gate, whence she could see a number of servants, swelling out their chests, pushing out their stomachs, gesticulating with their hands and kicking their feet about, while they were seated at the main entrance chattering about one thing and another.

Goody Liu felt constrained to edge herself forward. "Gentlemen," she ventured, "may happiness betide you!"

The whole company of servants scrutinised her for a time. "Where do you come from?" they at length inquired.

"I've come to look up Mr. Chou, an attendant of my lady's," remarked goody Liu, as she forced a smile; "which of you, gentlemen, shall I trouble to do me the favour of asking him to come out?"

The servants, after hearing what she had to say, paid, the whole number of them, no heed to her; and it was after the lapse of a considerable time that they suggested: "Go and wait at a distance, at the foot of that wall; and in a short while, the visitors, who are in their house, will be coming out."

Among the party of attendants was an old man, who interposed,

"Don't baffle her object," he expostulated; "why make a fool of her?" and turning to goody Liu: "This Mr. Chou," he said, "is gone south: his house is at the back row; his wife is anyhow at home; so go round this way, until you reach the door, at the back street, where, if you will ask about her, you will be on the right track."

Goody Liu, having expressed her thanks, forthwith went, leading Pan Erh by the hand, round to the back door, where she saw several pedlars resting their burdens. There were also those who sold things to eat, and those who sold playthings and toys; and besides these, twenty or thirty boys bawled and shouted, making quite a noise.

Goody Liu readily caught hold of one of them. "I'd like to ask you just a word, my young friend," she observed; "there's a Mrs. Chou here; is she at home?"

"Which Mrs. Chou?" inquired the boy; "we here have three Mrs. Chous; and there are also two young married ladies of the name of Chou. What are the duties of the one you want, I wonder ?"

"She's a waiting-woman of my lady," replied goody Liu.

"It's easy to get at her," added the boy; "just come along with me."

Leading the way for goody Liu into the backyard, they reached the wall of a court, when he pointed and said, "This is her house.--Mother Chou!" he went on to shout with alacrity; "there's an old lady who wants to see you."

Chou Jui's wife was at home, and with all haste she came out to greet her visitor. "Who is it?" she asked.

Goody Liu advanced up to her. "How are you," she inquired, "Mrs. Chou?"

Mrs. Chou looked at her for some time before she at length smiled and replied, "Old goody Liu, are you well? How many years is it since we've seen each other; tell me, for I forget just now; but please come in and sit."

"You're a lady of rank," answered goody Liu smiling, as she walked along, "and do forget many things. How could you remember such as ourselves?"

With these words still in her mouth, they had entered the house, whereupon Mrs. Chou ordered a hired waiting-maid to pour the tea. While they were having their tea she remarked, "How Pan Erh has managed to grow!" and then went on to make inquiries on the subject of various matters, which had occurred after their separation.

"To-day," she also asked of goody Liu, "were you simply passing by? or did you come with any express object?"

"I've come, the fact is, with an object!" promptly replied goody Liu; "(first of all) to see you, my dear sister-in-law; and, in the second place also, to inquire after my lady's health. If you could introduce me to see her for a while, it would be better; but if you can't, I must readily borrow your good offices, my sister-in-law, to convey my message."

Mr. Chou Jui's wife, after listening to these words, at once became to a great extent aware of the object of her visit. Her husband had, however, in years gone by in his attempt to purchase some land, obtained considerably the support of Kou Erh, so that when she, on this occasion, saw goody Liu in such a dilemma, she could not make up her mind to refuse her wish. Being in the second place keen upon making a display of her own respectability, she therefore said smilingly:

"Old goody Liu, pray compose your mind! You've come from far off with a pure heart and honest purpose, and how can I ever not show you the way how to see this living Buddha? Properly speaking, when people come and guests arrive, and verbal messages have to be given, these matters are not any of my business, as we all here have each one kind of duties to carry out. My husband has the special charge of the rents of land coming in, during the two seasons of spring and autumn, and when at leisure, he takes the young gentlemen out of doors, and then his business is done. As for myself, I have to accompany my lady and young married ladies on anything connected with out-of-doors; but as you are a relative of my lady and have besides treated me as a high person and come to me for help, I'll, after all, break this custom and deliver your message. There's only one thing, however, and which you, old lady, don't know. We here are not what we were five years before. My lady now doesn't much worry herself about anything; and it's entirely lady Secunda who looks after the menage. But who do you presume is this lady Secunda? She's the niece of my lady, and the daughter of my master, the eldest maternal uncle of by-gone days. Her infant name was Feng Ko."

"Is it really she?" inquired promptly goody Liu, after this explanation. "Isn't it strange? what I said about her years back has come out quite correct; but from all you say, shall I to-day be able to see her?"

"That goes without saying," replied Chou Jui's wife; "when any visitors come now-a-days, it's always lady Feng who does the honours and entertains them, and it's better to-day that you should see her for a while, for then you will not have walked all this way to no purpose."

"O mi to fu!" exclaimed old goody Liu; "I leave it entirely to your convenience, sister-in-law."

"What's that you're saying?" observed Chou Jui's wife. "The proverb says: 'Our convenience is the convenience of others.' All I have to do is to just utter one word, and what trouble will that be to me."

Saying this, she bade the young waiting maid go to the side pavilion, and quietly ascertain whether, in her old ladyship's apartment, table had been laid.

The young waiting-maid went on this errand, and during this while, the two of them continued a conversation on certain irrelevant matters.

"This lady Feng," observed goody Liu, "can this year be no older than twenty, and yet so talented as to manage such a household as this! the like of her is not easy to find!"

"Hai! my dear old goody," said Chou Jui's wife, after listening to her, "it's not easy to explain; but this lady Feng, though young in years, is nevertheless, in the management of affairs, superior to any man. She has now excelled the others and developed the very features of a beautiful young woman. To say the least, she has ten thousand eyes in her heart, and were they willing to wager their mouths, why ten men gifted with eloquence couldn't even outdo her! But by and bye, when you've seen her, you'll know all about her! There's only this thing, she can't help being rather too severe in her treatment of those below her."

While yet she spake, the young waiting-maid returned. "In her venerable lady's apartment," she reported, "repast has been spread, and already finished; lady Secunda is in madame Wang's chamber."

As soon as Chou Jui's wife heard this news, she speedily got up and pressed goody Liu to be off at once. "This is," she urged, "just the hour for her meal, and as she is free we had better first go and wait for her; for were we to be even one step too late, a crowd of servants will come with their reports, and it will then be difficult to speak to her; and after her siesta, she'll have still less time to herself."

As she passed these remarks, they all descended the couch together. Goody Liu adjusted their dresses, and, having impressed a few more words of advice on Pan Erh, they followed Chou Jui's wife through winding passages to Chia Lien's house. They came in the first instance into the side pavilion, where Chou Jui's wife placed old goody Liu to wait a little, while she herself went ahead, past the screen-wall and into the entrance of the court.

Hearing that lady Feng had not come out, she went in search of an elderly waiting-maid of lady Feng, P'ing Erh by name, who enjoyed her confidence, to whom Chou Jui's wife first recounted from beginning to end the history of old goody Liu.

"She has come to-day," she went on to explain, "from a distance to pay her obeisance. In days gone by, our lady used often to meet her, so that, on this occasion, she can't but receive her; and this is why I've brought her in! I'll wait here for lady Feng to come down, and explain everything to her; and I trust she'll not call me to task for officious rudeness."

P'ing Erh, after hearing what she had to say, speedily devised the plan of asking them to walk in, and to sit there pending (lady Feng's arrival), when all would be right.

Chou Jui's wife thereupon went out and led them in. When they ascended the steps of the main apartment, a young waiting-maid raised a red woollen portiere, and as soon as they entered the hall, they smelt a whiff of perfume as it came wafted into their faces: what the scent was they could not discriminate; but their persons felt as if they were among the clouds.

The articles of furniture and ornaments in the whole room were all so brilliant to the sight, and so vying in splendour that they made the head to swim and the eyes to blink, and old goody Liu did nothing else the while than nod her head, smack her lips and invoke Buddha. Forthwith she was led to the eastern side into the suite of apartments, where was the bedroom of Chia Lien's eldest daughter. P'ing Erh, who was standing by the edge of the stove-couch, cast a couple of glances at old goody Liu, and felt constrained to inquire how she was, and to press her to have a seat.

Goody Liu, noticing that P'ing Erh was entirely robed in silks, that she had gold pins fixed in her hair, and silver ornaments in her coiffure, and that her countenance resembled a flower or the moon (in beauty), readily imagined her to be lady Feng, and was about to address her as my lady; but when she heard Mrs. Chou speak to her as Miss P'ing, and P'ing Erh promptly address Chou Jui's wife as Mrs. Chou, she eventually became aware that she could be no more than a waiting-maid of a certain respectability.

She at once pressed old goody Liu and Pan Erh to take a seat on the stove-couch. P'ing Erh and Chou Jui's wife sat face to face, on the edges of the couch. The waiting-maids brought the tea. After they had partaken of it, old goody Liu could hear nothing but a "lo tang, lo tang" noise, resembling very much the sound of a bolting frame winnowing flour, and she could not resist looking now to the East, and now to the West. Suddenly in the great Hall, she espied, suspended on a pillar, a box at the bottom of which hung something like the weight of a balance, which incessantly wagged to and fro.

"What can this thing be?" communed goody Liu in her heart, "What can be its use?" While she was aghast, she unexpectedly heard a sound of "tang" like the sound of a golden bell or copper cymbal, which gave her quite a start. In a twinkle of the eyes followed eight or nine consecutive strokes; and she was bent upon inquiring what it was, when she caught sight of several waiting-maids enter in a confused crowd. "Our lady has come down!" they announced.

P'ing Erh, together with Chou Jui's wife, rose with all haste. "Old goody Liu," they urged, "do sit down and wait till it's time, when we'll come and ask you in."

Saying this, they went out to meet lady Feng.

Old goody Liu, with suppressed voice and ear intent, waited in perfect silence. She heard at a distance the voices of some people laughing, whereupon about ten or twenty women, with rustling clothes and petticoats, made their entrance, one by one, into the hall, and thence into the room on the other quarter. She also detected two or three women, with red-lacquered boxes in their hands, come over on this part and remain in waiting.

"Get the repast ready!" she heard some one from the offside say.

The servants gradually dispersed and went out; and there only remained in attendance a few of them to bring in the courses. For a long time, not so much as the caw of a crow could be heard, when she unexpectedly perceived two servants carry in a couch-table, and lay it on this side of the divan. Upon this table were placed bowls and plates, in proper order replete, as usual, with fish and meats; but of these only a few kinds were slightly touched.

As soon as Pan Erh perceived (all these delicacies), he set up such a noise, and would have some meat to eat, but goody Liu administered to him such a slap, that he had to keep away.

Suddenly, she saw Mrs. Chou approach, full of smiles, and as she waved her hand, she called her. Goody Liu understood her meaning, and at once pulling Pan Erh off the couch, she proceeded to the centre of the Hall; and after Mrs. Chou had whispered to her again for a while, they came at length with slow step into the room on this side, where they saw on the outside of the door, suspended by brass hooks, a deep red flowered soft portiere. Below the window, on the southern side, was a stove-couch, and on this couch was spread a crimson carpet. Leaning against the wooden partition wall, on the east side, stood a chain-embroidered back-cushion and a reclining pillow. There was also spread a large watered satin sitting cushion with a gold embroidered centre, and on the side stood cuspidores made of silver.

Lady Feng, when at home, usually wore on her head a front-piece of dark martin a la Chao Chuen, surrounded with tassels of strung pearls. She had on a robe of peach-red flowered satin, a short pelisse of slate-blue stiff silk, lined with squirrel, and a jupe of deep red foreign crepe, lined with ermine. Resplendent with pearl-powder and with cosmetics, she sat in there, stately and majestic, with a small brass poker in her hands, with which she was stirring the ashes of the hand-stove. P'ing Erh stood by the side of the couch, holding a very small lacquered tea-tray. In this tray was a small tea-cup with a cover. Lady Feng neither took any tea, nor did she raise her head, but was intent upon stirring the ashes of the hand-stove.

"How is it you haven't yet asked her to come in?" she slowly inquired; and as she spake, she turned herself round and was about to ask for some tea, when she perceived that Mrs. Chou had already introduced the two persons and that they were standing in front of her.

She forthwith pretended to rise, but did not actually get up, and with a face radiant with smiles, she ascertained about their health, after which she went in to chide Chou Jui's wife. "Why didn't you tell me they had come before?" she said.

Old goody Liu was already by this time prostrated on the ground, and after making several obeisances, "How are you, my lady?" she inquired.

"Dear Mrs. Chou," lady Feng immediately observed, "do pull her up, and don't let her prostrate herself! I'm yet young in years and don't know her much; what's more, I've no idea what's the degree of the relationship between us, and I daren't speak directly to her."

"This is the old lady about whom I spoke a short while back," speedily explained Mrs. Chou.

Lady Feng nodded her head assentingly.

By this time old goody Liu had taken a seat on the edge of the stove-couch. As for Pan Erh, he had gone further, and taken refuge behind her back; and though she tried, by every means, to coax him to come forward and make a bow, he would not, for the life of him, consent.

"Relatives though we be," remarked lady Feng, as she smiled, "we haven't seen much of each other, so that our relations have been quite distant. But those who know how matters stand will assert that you all despise us, and won't often come to look us up; while those mean people, who don't know the truth, will imagine that we have no eyes to look at any one."

Old goody Liu promptly invoked Buddha. "We are at home in great straits," she pleaded, "and that's why it wasn't easy for us to manage to get away and come! Even supposing we had come as far as this, had we not given your ladyship a slap on the mouth, those gentlemen would also, in point of fact, have looked down upon us as a mean lot."

"Why, language such as this," exclaimed lady Feng smilingly, "cannot help making one's heart full of displeasure! We simply rely upon the reputation of our grandfather to maintain the status of a penniless official; that's all! Why, in whose household is there anything substantial? we are merely the denuded skeleton of what we were in days of old, and no more! As the proverb has it: The Emperor himself has three families of poverty-stricken relatives; and how much more such as you and I?"

Having passed these remarks, she inquired of Mrs. Chou, "Have you let madame know, yes or no?"

"We are now waiting," replied Mrs. Chou, "for my lady's orders."

"Go and have a look," said lady Feng; "but, should there be any one there, or should she be busy, then don't make any mention; but wait until she's free, when you can tell her about it and see what she says."

Chou Jui's wife, having expressed her compliance, went off on this errand. During her absence, lady Feng gave orders to some servants to take a few fruits and hand them to Pan Erh to eat; and she was inquiring about one thing and another, when there came a large number of married women, who had the direction of affairs in the household, to make their several reports.

P'ing Erh announced their arrival to lady Feng, who said: "I'm now engaged in entertaining some guests, so let them come back again in the evening; but should there be anything pressing then bring it in and I'll settle it at once."

P'ing Erh left the room, but she returned in a short while. "I've asked them," she observed, "but as there's nothing of any urgency, I told them to disperse." Lady Feng nodded her head in token of approval, when she perceived Chou Jui's wife come back. "Our lady," she reported, as she addressed lady Feng, "says that she has no leisure to-day, that if you, lady Secunda, will entertain them, it will come to the same thing; that she's much obliged for their kind attention in going to the trouble of coming; that if they have come simply on a stroll, then well and good, but that if they have aught to say, they should tell you, lady Secunda, which will be tantamount to their telling her."

"I've nothing to say," interposed old goody Liu. "I simply come to see our elder and our younger lady, which is a duty on my part, a relative as I am."

"Well, if there's nothing particular that you've got to say, all right," Mrs. Chou forthwith added, "but if you do have anything, don't hesitate telling lady Secunda, and it will be just as if you had told our lady."

As she uttered these words, she winked at goody Liu. Goody Liu understood what she meant, but before she could give vent to a word, her face got scarlet, and though she would have liked not to make any mention of the object of her visit, she felt constrained to suppress her shame and to speak out.

"Properly speaking," she observed, "this being the first time I see you, my lady, I shouldn't mention what I've to say, but as I come here from far off to seek your assistance, my old friend, I have no help but to mention it."

She had barely spoken as much as this, when she heard the youths at the inner-door cry out: "The young gentleman from the Eastern Mansion has come."

Lady Feng promptly interrupted her. "Old goody Liu," she remarked, "you needn't add anything more." She, at the same time, inquired, "Where's your master, Mr. Jung?" when became audible the sound of footsteps along the way, and in walked a young man of seventeen or eighteen. His appearance was handsome, his person slender and graceful. He had on light furs, a girdle of value, costly clothes and a beautiful cap.

At this stage, goody Liu did not know whether it was best to sit down or to stand up, neither could she find anywhere to hide herself.

"Pray sit down," urged lady Feng, with a laugh; "this is my nephew!' Old goody Liu then wriggled herself, now one way, and then another, on to the edge of the couch, where she took a seat.

"My father," Chia Jung smilingly ventured, "has sent me to ask a favour of you, aunt. On some previous occasion, our grand aunt gave you, dear aunt, a stove-couch glass screen, and as to-morrow father has invited some guests of high standing, he wishes to borrow it to lay it out for a little show; after which he purposes sending it back again."

"You're late by a day," replied lady Feng. "It was only yesterday that I gave it to some one."

Chia Jung, upon hearing this, forthwith, with giggles and smiles, made, near the edge of the couch, a sort of genuflexion. "Aunt," he went on, "if you don't lend it, father will again say that I don't know how to speak, and I shall get another sound thrashing. You must have pity upon your nephew, aunt."

"I've never seen anything like this," observed lady Feng sneeringly; "the things belonging to the Wang family are all good, but where have you put all those things of yours? the only good way is that you shouldn't see anything of ours, for as soon as you catch sight of anything, you at once entertain a wish to carry it off."

"Pray, aunt," entreated Chia Jung with a smile, "do show me some compassion."

"Mind your skin!" lady Feng warned him, "if you do chip or spoil it in the least."

She then bade P'ing Erh take the keys of the door of the upstairs room and send for several trustworthy persons to carry it away.

Chia Jung was so elated that his eyebrows dilated and his eyes smiled. "I've brought myself," he added, with vehemence, "some men to take it away; I won't let them recklessly bump it about."

Saying this, he speedily got up and left the room.

Lady Feng suddenly bethought herself of something, and turning towards the window, she called out, "Jung Erh, come back." Several servants who stood outside caught up her words: "Mr. Jung," they cried, "you're requested to go back;" whereupon Chia Jung turned round and retraced his steps; and with hands drooping respectfully against his sides, he stood ready to listen to his aunt's wishes.

Lady Feng was however intent upon gently sipping her tea, and after a good long while of abstraction, she at last smiled: "Never mind," she remarked; "you can go. But come after you've had your evening meal, and I'll then tell you about it. Just now there are visitors here; and besides, I don't feel in the humour."

Chia Jung thereupon retired with gentle step.

Old goody Liu, by this time, felt more composed in body and heart. "I've to-day brought your nephew," she then explained, "not for anything else, but because his father and mother haven't at home so much as anything to eat; the weather besides is already cold, so that I had no help but to take your nephew along and come to you, old friend, for assistance!"

As she uttered these words, she again pushed Pan Erh forward. "What did your father at home tell you to say?" she asked of him; "and what did he send us over here to do? Was it only to give our minds to eating fruit?"

Lady Feng had long ago understood what she meant to convey, and finding that she had no idea how to express herself in a decent manner, she readily interrupted her with a smile. "You needn't mention anything," she observed, "I'm well aware of how things stand;" and addressing herself to Mrs. Chou, she inquired, "Has this old lady had breakfast, yes or no?"

Old goody Liu hurried to explain. "As soon as it was daylight," she proceeded, "we started with all speed on our way here, and had we even so much as time to have any breakfast?"

Lady Feng promptly gave orders to send for something to eat. In a short while Chou Jui's wife had called for a table of viands for the guests, which was laid in the room on the eastern side, and then came to take goody Liu and Pan Erh over to have their repast.

"My dear Mrs. Chou," enjoined lady Feng, "give them all they want, as I can't attend to them myself;" which said, they hastily passed over into the room on the eastern side.

Lady Feng having again called Mrs. Chou, asked her: "When you first informed madame about them, what did she say?" "Our Lady observed," replied Chou Jui's wife, "that they don't really belong to the same family; that, in former years, their grandfather was an official at the same place as our old master; that hence it came that they joined ancestors; that these few years there hasn't been much intercourse (between their family and ours); that some years back, whenever they came on a visit, they were never permitted to go empty-handed, and that as their coming on this occasion to see us is also a kind attention on their part, they shouldn't be slighted. If they've anything to say," (our lady continued), "tell lady Secunda to do the necessary, and that will be right."

"Isn't it strange!" exclaimed lady Feng, as soon as she had heard the message; "since we are all one family, how is it I'm not familiar even with so much as their shadow?"

While she was uttering these words, old goody Liu had had her repast and come over, dragging Pan Erh; and, licking her lips and smacking her mouth, she expressed her thanks.

Lady Feng smiled. "Do pray sit down," she said, "and listen to what I'm going to tell you. What you, old lady, meant a little while back to convey, I'm already as much as yourself well acquainted with! Relatives, as we are, we shouldn't in fact have waited until you came to the threshold of our doors, but ought, as is but right, to have attended to your needs. But the thing is that, of late, the household affairs are exceedingly numerous, and our lady, advanced in years as she is, couldn't at a moment, it may possibly be, bethink herself of you all! What's more, when I took over charge of the management of the menage, I myself didn't know of all these family connections! Besides, though to look at us from outside everything has a grand and splendid aspect, people aren't aware that large establishments have such great hardships, which, were we to recount to others, they would hardly like to credit as true. But since you've now come from a great distance, and this is the first occasion that you open your mouth to address me, how can I very well allow you to return to your home with empty hands! By a lucky coincidence our lady gave, yesterday, to the waiting-maids, twenty taels to make clothes with, a sum which they haven't as yet touched, and if you don't despise it as too little, you may take it home as a first instalment, and employ it for your wants."

When old goody Liu heard the mention made by lady Feng of their hardships, she imagined that there was no hope; but upon hearing her again speak of giving her twenty taels, she was exceedingly delighted, so much so that her eyebrows dilated and her eyes gleamed with smiles.

"We too know," she smilingly remarked, "all about difficulties! but the proverb says, 'A camel dying of leanness is even bigger by much than a horse!' No matter what those distresses may be, were you yet to pluck one single hair from your body, my old friend, it would be stouter than our own waist."

Chou Jui's wife stood by, and on hearing her make these coarse utterances, she did all she could to give her a hint by winking, and make her desist. Lady Feng laughed and paid no heed; but calling P'ing Erh, she bade her fetch the parcel of money, which had been given to them the previous day, and to also bring a string of cash; and when these had been placed before goody Liu's eyes: "This is," said lady Feng, "silver to the amount of twenty taels, which was for the time given to these young girls to make winter clothes with; but some other day, when you've nothing to do, come again on a stroll, in evidence of the good feeling which should exist between relatives. It's besides already late, and I don't wish to detain you longer and all for no purpose; but, on your return home, present my compliments to all those of yours to whom I should send them."

As she spake, she stood up. Old goody Liu gave utterance to a thousand and ten thousand expressions of gratitude, and taking the silver and cash, she followed Chou Jui's wife on her way to the out-houses. "Well, mother dear," inquired Mrs. Chou, "what did you think of my lady that you couldn't speak; and that whenever you opened your mouth it was all 'your nephew.' I'll make just one remark, and I don't mind if you do get angry. Had he even been your kindred nephew, you should in fact have been somewhat milder in your language; for that gentleman, Mr. Jung, is her kith and kin nephew, and whence has appeared such another nephew of hers (as Pan Erh)?"

Old goody Liu smiled. "My dear sister-in-law," she replied, "as I gazed upon her, were my heart and eyes, pray, full of admiration or not? and how then could I speak as I should?"

As they were chatting, they reached Chou Jui's house. They had been sitting for a while, when old goody Liu produced a piece of silver, which she was purposing to leave behind, to be given to the young servants in Chou Jui's house to purchase fruit to eat; but how could Mrs. Chou satiate her eye with such a small piece of silver? She was determined in her refusal to accept it, so that old goody Liu, after assuring her of her boundless gratitude, took her departure out of the back gate she had come in from.

Reader, you do not know what happened after old goody Liu left, but listen to the explanation which will be given in the next chapter.

请欣赏:

请给我换一个看看! 拜托,快把噪音停掉!我读累了,想听点音乐或者请来支歌曲!

【选集】紅樓一春夢 |

|

|