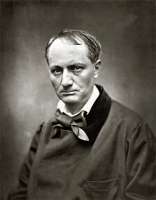

阅读夏尔·波德莱尔 Charles Baudelaire在诗海的作品!!! | |||

法国诗人。生于巴黎。幼年丧父,母亲改嫁。继父欧皮克上校后来擢升将军,在第二帝国时期被任命为法国驻西班牙大使。他不理解波德莱尔的诗人气质和复杂心情,波德莱尔也不能接受继父的专制作风和高压手段,于是欧皮克成为波德莱尔最憎恨的人。但波德莱尔对母亲感情深厚。这种不正常的家庭关系,不可避免地影响诗人的精神状态和创作情绪。波德莱尔对资产阶级的传统观念和道德价值采取了挑战的态度。他力求挣脱本阶级思想意识的枷锁,探索着在抒情诗的梦幻世界中求得精神的平衡。在这个意义上,波德莱尔是资产阶级的浪子。1848年巴黎工人武装起义,反对复辟王朝,波德莱尔登上街垒,参加战斗。

成年以后,波德莱尔继承了生父的遗产,和巴黎文人艺术家交游,过着波希米亚人式的浪荡生活。他的主要诗篇都是在这种内心矛盾和苦闷的气氛中创作的。

奠定波德莱尔在法国文学史上的重要地位的作品,是诗集《恶之花》。这部诗集1857年初版问世时,只收100首诗。1861年再版时,增为129首。以后多次重版,陆续有所增益。其中诗集一度被认为是淫秽的读物,被当时政府禁了其中的6首诗,并进行罚款。此事对波德莱尔冲击颇大。从题材上看,《恶之花》歌唱醇酒、美人,强调官能陶醉,似乎诗人愤世嫉俗,对现实生活采取厌倦和逃避的态度。实质上作者对现实生活不满,对客观世界采取了绝望的反抗态度。他揭露生活的阴暗面,歌唱丑恶事物,甚至不厌其烦地描写一具《腐尸》蛆虫成堆,恶臭触鼻,来表现其独特的爱情观。(那时,我的美人,请告诉它们,/那些吻吃你的蛆子,/旧爱虽已分解,可是,我已保存/爱的形姿和爱的神髓!)他的诗是对资产阶级传统美学观点的冲击。

历来对于波德莱尔和《恶之花》有各种不同的评论。保守的评论家认为波德莱尔是颓废诗人,《恶之花》是毒草。资产阶级权威学者如朗松和布吕纳介等,对波德莱尔也多所贬抑。但他们不能不承认《恶之花》的艺术特色,朗松在批评波德莱尔颓废之后,又肯定他是“强有力的艺术家”。诗人雨果曾给波德莱尔去信称赞这些诗篇“象星星一般闪耀在高空”。雨果说:“《恶之花》的作者创作了一个新的寒颤。”

波德莱尔不但是法国象征派诗歌的先驱,而且是现代主义的创始人之一。现代主义认为,美学上的善恶美丑,与一般世俗的美丑善恶概念不同。现代主义所谓美与善,是指诗人用最适合于表现他内心隐秘和真实的感情的艺术手法,独特地完美地显示自己的精神境界。《恶之花》出色地完成这样的美学使命。

《恶之花》的“恶”字,法文原意不仅指恶劣与罪恶,也指疾病与痛苦。波德莱尔在他的诗集的扉页上写给诗人戈蒂耶的献词中,称他的诗篇为“病态之花”,认为他的作品是一种“病态”的艺术。他对于使他遭受“病”的折磨的现实世界怀有深刻的仇恨。他给友人的信中说:“在这部残酷的书中,我注入了自己的全部思想,整个的心(经过改装的),整个宗教意识,以及全部仇恨。”这种仇恨情绪之所以如此深刻,正因它本身反映着作者对于健康、光明、甚至“神圣”事物的强烈向往。

波德莱尔除诗集《恶之花》以外,还发表了独具一格的散文诗集《巴黎的忧郁》(1869)和《人为的天堂》(1860)。他的文学和美术评论集《美学管窥》(1868)和《浪漫主义艺术》在法国的文艺评论史上也有一定的地位。波德莱尔还翻译美国诗人爱伦·坡的《怪异故事集》和《怪异故事续集》。

波德莱尔对象征主义诗歌的贡献之一,是他针对浪漫主义的重情感而提出重灵性。所谓灵性,其实就是思想。他总是围绕着一个思想组织形象,即使在某些偏重描写的诗中,也往往由于提出了某种观念而改变了整首诗的含义。

【年表】

1821年 夏尔·波德莱尔生于巴黎高叶街十五号

1827年 波德莱尔的父亲让—弗朗索瓦·波德莱尔去世

1828年 母亲再婚,改嫁欧比克上校

1831年 欧比克调至里昂驻防,全家随同前往。波德莱尔入德洛姆寄宿学校

1832年 进里昂皇家中学

1836年 欧比克调回巴黎,波德莱尔进路易大帝中学就读。开始阅读夏多布里昂和圣伯夫

1837年 在中学优等生会考中获拉丁诗二等奖

1838年 去比利牛斯山旅行,初写田园诗

1839年 被路易大帝中学开除。通过中学毕业会考

1840年 入勒韦克·巴伊寄宿学校。开始游手好闲,与继父闹翻

1841年 被迫远游,从波尔多出发,前往加尔各答

1842年 回巴黎,继承先父遗产。迁居圣·路易岛,开始与圣伯夫、戈蒂耶、雨果及女演 员 让娜·杜瓦尔交往。写出《恶之花》中的二十多首诗

1843年 经济拮据。吸大麻。《恶之花》中的许多诗写于此时

1844年 被指定监护人管理其财产,挥霍无度

1845年 二度企图自杀。出版《1845年的沙龙》。开始翻译爱伦·坡的作品

1846年 出版《1846年的沙龙》

1847年 结识玛丽·杜布伦,发表小说《拉·芳法罗》

1848年 参加革命团体。翻译爱伦·坡的《磁性启示》

1849年 对革命感到失望,躲到第戎数月

1851年 发表《酒与印度大麻》,以《冥府》为总题发表十一首诗,后收入《恶之花》。控诉雾月政变,放弃所有政治活动

1852年 发表《爱伦·坡的生平与著作》。首次寄诗给萨巴蒂埃夫人

1855年 在《两世界评论》杂志以《恶之花》为题发表十八首诗

1857年 《恶之花》初版,惹官司。与萨巴蒂埃断交

1858年 回母亲身边居住,经济困难

1859年 出版《1859年的沙龙》,精神日益不安

1860年 出版《人造天堂》

1861年 再次企图自杀。《恶之花》重版。提名为法兰西学士院院士候选人。写《赤裸的心》

1862年 退出候选,健康不佳

1863年《小散文诗》初版

1864年 以《巴黎的忧郁》为题发表五首新写的散文诗。前往比利时。出版和赚钱计划落空。写《比利时讽刺集》

1865年 写《赤裸的心》。写《可怜的比利时》。病情恶化,回巴黎

1866年 出版散诗集《漂流物》。参观比利时圣·卢教堂时突然跌倒。失语,半身不遂,送疗养院

1867年 去世。《恶之花》三版

Biography

Early life

Baudelaire was born in Paris, France in 1821. His father, a senior civil servant and amateur artist, died early in Baudelaire's life in 1827. The following year, his mother, Caroline, thirty-four years younger than his father, married Lieutenant Colonel Jacques Aupick, who later became a French ambassador to various noble courts. Baudelaire’s relationship with his mother was a close and complex one, and it dominated his life.[1] He later stated, “I loved my mother for her elegance. I was a precocious dandy.” He later wrote to her, “There was in my childhood a period of passionate love for you”. [2] Aupick, a rigid disciplinarian, though concerned for Baudelaire upbringing and future, quickly came at odds with his stepson’s artistic temperament. [3]

Baudelaire was educated in Lyon, where he was forced to board away from his mother (even during holidays) and accept his stepfather’s rigid methods, which included depriving him of visits home when his grades slipped. He wrote when recalling those times, “a shudder at the grim years of claustration…the unease of wretched and abandoned childhood, the hatred of tyrannical schoolfellows, and the solitude of the heart.” [4]At fourteen, Baudelaire was described by a classmate, “He was much more refined and distinguished than any of our fellow pupils…we are bound to one another…by shared tastes and sympathies, the precocious love of fine works of literature.” [5]Later, he attended the Lycée Louis-le-Grand in Paris. Baudelaire was erratic in his studies, at times diligent, at other times prone to “idleness”.

At eighteen, Baudelaire was described as “an exalted character, sometimes full of mysticism, and sometimes full of immorality and cynicism (which were excessive but only verbal)”. [6]Upon gaining his degree in 1839, he was undecided about his future. He told his brother, “I don’t feel I have a vocation for anything”. His stepfather had in mind a career in law or diplomacy, but instead Baudelaire decided to embark upon a literary career, and for the next two years led an irregular life, socializing with other bohemian artists and writers. [7]

Baudelaire began to frequent prostitutes and may have contracted gonorrhea and syphilis during this period. He went to a pharmacist known for venereal disease treatments, upon the recommendation of his older brother Alphonse, a magistrate. [8]For a while, he took on a prostitute “Sara” as his mistress and lived with his brother when his funds were low. His stepfather kept him on a tight allowance which he spent as quickly as he received it. Baudelaire began to run up debts, mostly for clothes. His stepfather demanded an accounting and wrote to Alphonse, “The moment has come when something must be done to save your brother from absolute perdition”.[9] In the hope of reforming him and making a man of him, his stepfather sent him on a voyage to Calcutta, India in 1841, under the care of a former naval captain. Baudelaire’s mother was distressed by both his poor behavior and the proposed solution. [10]

The arduous trip, however, did nothing to turn Baudelaire’s mind away from a literary career or from his casual attitude toward life, so the naval captain agreed to let Baudelaire return home. Though Baudelaire later exaggerated his aborted trip to create a legend about his youthful travels and experiences, including “riding on elephants”, the trip did provide strong impressions of the sea, sailing, and exotic ports, that he later employed in his poetry. [11]When Baudelaire returned to Paris, after less than a year's absence, much to his parents chagrin, he was more determined than ever to continue with his literary career. His mother later recalled, “Oh, what grief! If Charles had let himself be guided by his stepfather, his career would have been very different…He would not have left a name in literature, it is true, but we should have been happier, all three of us”. [12]

Soon, Baudelaire returned to the taverns to philosophize and to recite his unpublished poems, and to enjoy the adulation of his artistic peers. At twenty-one, he received a good-sized inheritance of over 100,00 francs, plus four parcels of land, but spent much of it within a few years, including borrowing heavily against his mortgages. He quickly piled up debts far exceeding his annual income and out of desperation, his family obtained a decree to place his property in trust. [13] During this time he met Jeanne Duval, the illegitimate daughter of a prostitute from Nantes, who was to become his longest romantic association. She had been the mistress of the caricaturist and photographer Nadar. His mother thought Jeanne a “Black Venus” who “tortured him in every way” and drained him of money at every opportunity. [14]

Career

While still unpublished in 1843, Baudelaire became known in artistic circles as a dandy and free-spender, buying up books, art, and antiques he couldn’t afford. By 1844, he was eating on credit and half his inheritance was gone. Baudelaire regularly implored his mother for money while he tried to advance his career. He met Balzac around this time and began to write many of the poems which would appear in Les Fleurs du mal ("The Flowers of Evil"). [15]His first published work was his art review Salon of 1845, which attracted immediate attention for its boldness. Many of his critical opinions were novel in their time, including his championing of Delacroix, but have since been generally accepted. Baudelaire proved himself to be a well-informed and passionate critic and he gained the attention of the greater art community.[16]That summer, however, despondent about his meager income, rising debts, loneliness, and doubtful future, because “the fatigue of falling asleep and the fatigue of waking are unbearable”, he decided to commit suicide and leave the remainder of his inheritance to his mistress. However, he lost his resolve and wounded himself with a knife only superficially. He implored his mother to visit him as he recovered but she ignored his pleas, perhaps under orders from her husband. [17]For a time, Baudelaire was homeless and completely estranged from his parents, until they relented due to his poor condition.

In 1846, Baudelaire wrote his second Salon review, gaining additional credibility as a advocate and critic of Romanticism. His support of Delacroix as the foremost Romantic artist, gained widespread notice. [18]The following year Baudelaire’s novella La Fanfarlo was published.

Baudelaire took part in the Revolutions of 1848. [19] For some years, he was interested in republican politics; but his political tendencies were more emotional positions than steadfast convictions, spanning the anarchism of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, the history of the Raison d'Ėtat of Giuseppe Ferrari, and ultramontane critique of liberalism of Joseph de Maistre. His stepfather, also caught up in the Revolution, survived the mob and was appointed envoy extraordinary to Turkey by the new government, despite his ties to the deposed royal family. [20]

In the early 1850’s, Baudelaire struggled with poor health, pressing debts, and irregular literary output. He often moved from one lodging to another, and maintained an uneasy relationship with his mother, frequently imploring her by letter for money. (Her letters to him have not been found). [21] He received many projects that he was unable to complete, though he did finish translations of stories by Edgar Allan Poe which were published in La Pays. [22] Baudelaire had learned English in his childhood, and Gothic novels, such as Lewis's The Monk, and Poe’s short stories, became some of his favorite reading matter, and major influences.

Upon the death of his stepfather in 1857, Baudelaire received no mention in the will, but he was heartened nonetheless that the division with his mother might now be mended. Still strongly tied to her emotionally, at thirty-six he wrote her, “believe that I belong to you absolutely, and that I belong only to you”. [23]

The Flowers of Evil

Baudelaire was a slow and fastidious worker, often sidetracked by indolence, emotional distress, and illness, and it was not until 1857 that he published his first and most famous volume of poems, Les Fleurs du mal ("The Flowers of Evil"), originally titled Les Limbes. [24]Some of these poems had already appeared in the Revue des deux mondes (Review of Two Worlds), when they were published by Baudelaire's friend Auguste Poulet Malassis, who had inherited a printing business at Alençon.

The poems found a small, appreciative audience, but greater public attention was given to their subject matter. The effect on fellow artists was, as Théodore de Banville stated, “immense, prodigious, unexpected, mingled with admiration and with some indefinable anxious fear”. [25]Flaubert, recently attacked in a similar fashion for Madame Bovary (and acquitted), was impressed and wrote Baudelaire, “You have found a way to rejuvenate Romanticism…You are as unyielding as marble, and as penetrating as an English mist”. [26]

The principal themes of sex and death were considered scandalous. He also touched on lesbianism, sacred and profane love, metamorphosis, melancholy, the corruption of the city, lost innocence, the oppressiveness of living, and wine. Notable in some poems is Baudelaire’s use of imagery of the sense of smell and of fragrances, which is used to evoke feelings of nostalgia and past intimacy. [27]

The book, however, quickly became a byword for unwholesomeness among mainstream critics of the day. Some critics called a few of the poems “masterpieces of passion, art, and poetry” but other poems were deemed to merit no less than legal action to suppress them. [28]J. Habas writing in Le Figaro, led the charge against Baudelaire, writing, “Everything in it which is not hideous is incomprehensible, everything one understands is putrid”. Then Baudelaire responded to the outcry, in a prophetic letter to his mother:

“You know that I have always considered that literature and the arts pursue an aim independent of morality. Beauty of conception and style is enough for me. But this book, whose title: Fleurs du mal, —says everything, is clad, as you will see, in a cold and sinister beauty. It was created with rage and patience. Besides, the proof of its positive worth is in all the ill that they speak of it. The book enrages people. Moreover, since I was terrified myself of the horror that I should inspire, I cut out a third from the proofs. They deny me everything, the spirit of invention and even the knowledge of the French language. I don’t care a rap about all these imbeciles, and I know that this book, with its virtues and its faults, will make its way in the memory of the lettered public, beside the best poems of V. Hugo, Th. Gautier and even Byron.” [29]

Baudelaire, his publisher, and the printer were successfully prosecuted for creating an offense against public morals. They were fined but Baudelaire was not imprisoned.[30]Six of the poems were suppressed, but printed later as Les Épaves ("The Wrecks") (Brussels, 1866). Another edition of Les Fleurs du mal, without these poems, but with considerable additions, appeared in 1861. Many notables rallied behind Baudelaire and condemned the sentence. Victor Hugo wrote him, “Your fleur du mal shine and dazzle like stars…I applaud your vigorous spirit with all my might”. [31]Baudelaire did not appeal the judgment but his fine was reduced. Nearly 100 years later, on May 11, 1949, Baudelaire was vindicated, the judgment officially reversed, and the six banned poems reinstated in France. [32]

In the poem "Au lecteur" ("To the Reader") that prefaces Les Fleurs du mal, Baudelaire accuses his readers of hypocrisy and of being as guilty of sins and lies as the poet:

... If rape or arson, poison, or the knife

Has wove no pleasing patterns in the stuff

Of this drab canvas we accept as life—

It is because we are not bold enough!

(Roy Campbell's translation)

Final years

Baudelaire next worked on a translation and adaptation of De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium Eater. [33]Other works in the years that followed included Petits Poèmes en prose ("Small Prose poems"); a series of art reviews published in the Pays, Exposition universelle ("Country, World Fair"); studies on Gustave Flaubert (in L'Artiste, October 18, 1857); on Théophile Gautier (Revue contemporaine, September, 1858); various articles contributed to Eugene Crepet's Poètes francais; Les Paradis artificiels: opium et haschisch ("French poets; Artificial Paradises: opium and hashish") (1860); and Un Dernier Chapitre de l'histoire des oeuvres de Balzac ("A Final Chapter of the history of works of Balzac") (1880), originally an article entitled "Comment on paye ses dettes quand on a du génie" ("How one pays one's debts when one has genius"), in which his criticism turns against his friends Honoré de Balzac, Théophile Gautier, and Gérard de Nerval.

Jeanne Duval, in a painting by Edward ManetBy 1859, his illnesses, his long-term use of laudanum, his life of stress and poverty had taken a toll and Baudelaire had aged noticeably. But at last, his mother relented and agreed to let him live with her for a while at Honfleur. Baudelaire was productive and at peace in the seaside town, his poem Le Voyage being one example of his efforts during that time. [34]In 1860, he became an ardent supporter of Richard Wagner.

His financial difficulties increased again, however, particularly after his publisher Poulet Malassis went bankrupt in 1861. In 1864, he left Paris for Belgium, partly in the hope of selling the rights to his works and also to give lectures. [35] His long-standing relationship with Jeanne Duval continued on-and-off, and he helped her to the end of his life. Baudelaire’s relationships with actress Marie Daubrun and with courtesan Apollonie Sabatier, though the source of much inspiration, never produced any lasting satisfaction. He smoked opium, and in Brussels he began to drink to excess. Baudelaire suffered a massive stroke in 1866 and paralysis followed. The last two years of his life were spent, in a semi-paralyzed state, in "maisons de santé" in Brussels and in Paris, where he died on August 31, 1867. Baudelaire is buried in the Cimetière du Montparnasse, Paris.

After his death, his mother paid off his substantial debts. For all her suffering over her son’s life, at last she found some comfort in Baudelaire’s emerging fame, “I see that my son, for all his faults, has his place in literature”. She lived another four years.[36]Many of Baudelaire’s works were published posthumously.

Associations

Baudelaire was an active participant in the artistic life of his times. As critic and essayist, he wrote extensively and perceptively about the luminaries and themes of French culture. He was frank with friends and enemies, rarely took the diplomatic approach, and sometimes responded violently verbally, which often undermined his cause. [37] His associations were numerous and included: Gustave Courbet, Honoré Daumier, Franz Liszt, Champfleury, Victor Hugo, Gustave Flaubert, Balzac, and the artists and writers that follow.

Poe

In 1846 and 1847, Baudelaire became acquainted with the works of Edgar Allan Poe, in which he found tales and poems that had, he claimed, long existed in his own brain but never taken shape. Baudelaire had much in common with Poe (who died in 1849 at age forty). Both had a similar sensibility, and macabre and supernatural turn of mind; both struggled with illness, poverty, and melancholy. Baudelaire saw in Poe a precursor and tried to be “his heir in all things”. [38]From this time until 1865, he was largely occupied with translating Poe's works; his translations were widely praised. Baudelaire was not the first French translator of Poe, but his “scrupulous translations” were considered among the best. These were published as Histoires extraordinaires ("Extraordinary stories") (1852), Nouvelles histoires extraordinaires ("New extraordinary stories") (1857), Aventures d'Arthur Gordon Pym, Eureka, and Histoires grotesques et sérieuses ("Grotesque and serious stories") (1865). Two essays on Poe are to be found in his Oeuvres complètes ("Complete works") (vols. v. and vi.).

Delacroix

A strong supporter of the Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix, Baudelaire called him “a poet in painting”. Baudelaire also absorbed much of Delacroix’s aesthetic ideas as expressed in his journals. As Baudelaire elaborated in his ‘’Salon of 1846’’, “As one contemplates his series of pictures, one seems to be attending the celebration of some grievous mystery…This grave and lofty melancholy shines with a dull light…plaintive and profound like a melody by Weber”. [39]Delacroix, though appreciative, kept his distance from Baudelaire, particularly after the scandal of Les Fleurs du mal. In private correspondence, Delacroix stated that Baudelaire “really gets on my nerves” and he expressed his unhappiness with Baudelaire’s persistent comments about “melancholy” and “feverishness”.[40]

Wagner

Baudelaire had no formal musical training, and knew little of composers behind Beethoven and Carl Maria von Weber. Weber was in some ways Wagner’s precursor, using the leitmotif and conceiving the idea of the “total art work” (“Gesamtkunstwerk”), both of which found Baudelaire’s admiration. Before even hearing Wagner’s music, Baudelaire studied reviews and essays about him, and formulated his impressions. Later, Baudelaire’s put them into his non-technical analysis of Wagner, which was highly regarded, particularly his essay Richard Wagner et Tannhäuser a Pàris. [41] Baudelaire’s reaction to music was passionate and psychological, “Music engulfs (possesses) me like the sea”. [42]After attending three Wagner concerts in Paris in 1860, Baudelaire wrote the composer, “I had a feeling of pride and joy in understanding, in being possessed, in being overwhelmed, a truly sensual pleasure like that of rising in the air”. [43] Baudelaire’s writings contributed to the elevation of Wagner and to the cult of Wagnerism that swept Europe in the following decades.

Gautier

Théophile Gautier, writer and poet, earned Baudelaire’s respect for his perfection of form and his mastery of language, though Baudelaire thought he lacked deeper emotion and spirituality. Both strove to express the artist’s inner vision, which Heinrich Heine had earlier stated, “In artistic matters, I am a supernaturalist. I believe that the artist can not find all his forms in nature, but that the most remarkable are revealed to him in his soul”. [44]Gautier’s frequent meditations on death and the horror of life are themes which influenced Baudelaire writings. In gratitude for their friendship and commonality of vision, Baudelaire dedicated Les Fleurs du mal to his colleague.

Manet

Edouard Manet and Baudelaire became constant companions starting around 1855. In the early 1860’s, Baudelaire accompanied Manet on daily sketching trips and often met him socially. He also lent Baudelaire money and looked after his affairs, particularly when Baudelaire went to Belgium. Baudelaire encouraged Manet to strike his own path and not succumb to criticism, “Manet has great talent, a talent which will stand the test of time. But he has a weak character. He seems to me crushed and stunned by shock”. [45] In his painting L’Atelier, Manet includes portraits of his friends Théophile Gautier, Jacques Offenbach, and Baudelaire. [46]While its difficult to differentiate who influenced whom, both Manet and Baudelaire discussed and expressed some common themes through their respective arts. Baudelaire praised the modernity of Manet’s subject matter, “almost all our originality comes from the stamp that ‘’time’’ imprints upon our feelings”. [47]When Manet’s famous Olympia (1865), a portrait of a nude courtesan, provoked a scandal for its blatant realism, Baudelaire worked privately to support his friend, though he offered no public defense (though he was ill at the time). When Baudelaire returned from Belgium after his stroke, Manet and his wife were frequent visitors at the nursing home and she would play passages from Wagner for Bauderlaire on the piano. [48]

Nadar

Nadar (Félix Tournachon) was a noted caricaturist, scientist, and important early photographer. Baudelaire admired Nadar, one of his closest friends, and wrote “Nadar is the most amazing manifestation of vitality”. [49]They moved in similar circles and Baudelaire made many social connections through him. Nadar’s ex-mistress Jeanne Duval became Baudelaire’s life-long mistress around 1842. Baudelaire became interested in photography in the 1850’s and denounced it as an art form and advocated for its return to “its real purpose, which is that of being the servant to the sciences and arts”. Photography should not, according to Baudelaire, encroach upon “the domain of the impalpable and the imaginary”. [50]Nadar remained a stalwart friend right to Baudelaire’s last days and wrote his obituary notice in Le Figaro.

Philosophy

Many of Baudelaire’s philosophical proclamations were considered scandalous and intentionally provocative in his time. He wrote on a wide range of subjects, drawing criticism and outrage from many quarters.

Love

“There is an invincible taste for prostitution in the heart of man, from which comes his horror of solitude. He wants to be ‘’two’’. The man of genius wants to be ‘’one’’…It is this horror of solitude, the need to lose oneself in the external flesh, that man nobly calls ‘’the need to love.’’.” [51]

Marriage

“Unable to suppress love, the Church wanted at least to disinfect it, and it created marriage”. [52]

The Artist

“The more a man cultivates the arts, the less randy he becomes…Only the brute is good at coupling, and copulation is the lyricism of the masses. To copulate is to enter into another—and the artist never emerges from himself”. [53]

Pleasure

“Personally, I think that the unique and supreme delight lies in the certainty of doing ’’evil’’—and men and women know from birth that all pleasure lies in evil.” [54]

Nature

“I should like the fields tinged with red, the rivers yellow, and the trees painted blue. Nature has no imagination.” [55]

Politics

I have no convictions, as they are understood by the men of my century, because I have no ambition…However, I have some convictions, in a nobler sense, which cannot be understood by the men of my time”. [56]

Influence

Portrait by Gustave Courbet, 1848.Baudelaire's influence on the direction of modern French- and English-language literature was considerable. The most significant French writers to come after him were generous with tributes; four years after his death, Arthur Rimbaud praised him in a letter as 'the king of poets, a true God'.[57] In 1895, Stéphane Mallarmé published a sonnet in Baudelaire's memory, 'Le Tombeau de Charles Baudelaire'. Marcel Proust, in an essay published in 1922, stated that along with Alfred de Vigny, Baudelaire was 'the greatest poet of the nineteenth century'.[58]

In the English-speaking world, Edmund Wilson credited Baudelaire as providing an initial impetus for the Symbolist movement, by virtue of his translations of Poe.[59] In 1930 T. S. Eliot, while asserting that Baudelaire had not yet received a “just appreciation” even in France, claimed that the poet had “great genius” and asserted that his “technical mastery which can hardly be overpraised... has made his verse an inexhaustible study for later poets, not only in his own language.”[60]

At the same time that Eliot was affirming Baudelaire's importance from a broadly conservative and explicitly Christian viewpoint,[61] left-wing critics such as Wilson and Walter Benjamin were able to do so from a dramatically different perspective. Benjamin translated Baudelaire's Tableaux Parisiens into German and published a major essay on translation[62] as the foreword.

In the late 1930s, Benjamin used Baudelaire as a starting point and focus for his monumental attempt at a materialist assessment of 19th century culture, Das Passagenwerk.[63] For Benjamin, Baudelaire's importance lay in his anatomies of the crowd, of the city and of modernity.[64]

Baudelaire was also an influence on H. P. Lovecraft, serving as a model for Lovecraft's decadent and evil characters in both "The Hound" and "Hypnos".[citation needed]

See also

Baudelaire signatureÉpater la bourgeoisie

Bibliography

Tomb of BaudelaireSalon de 1845, 1845

Salon de 1846, 1846

La Fanfarlo, 1847

Les Fleurs du mal, 1857

Les paradis artificiels, 1860

Réflexions sur Quelques-uns de mes Contemporains, 1861

Le Peintre de la Vie Moderne, 1863

Curiosités Esthétiques, 1868

L'art romantique, 1868

Le Spleen de Paris/Petits Poèmes en Prose, 1869

Oeuvres Posthumes et Correspondance Générale, 1887-1907

Fusées, 1897

Mon Coeur Mis à Nu, 1897

Oeuvres Complètes, 1922-53 (19 vols.)

Mirror of Art, 1955

The Essence of Laughter, 1956

Curiosités Esthétiques, 1962

The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays, 1964

Baudelaire as a Literary Critic, 1964

Arts in Paris 1845-1862, 1965

_Select_ed Writings on Art and Artist, 1972

_Select_ed Letters of Charles Baudelaire, 1986

Critique d'art; Critique musicale, 1992

Online texts

Charles Baudelaire Largest site dedicated to Baudelaire's poems and prose, containing Fleurs du mal, Petit poemes et prose, Fanfarlo and more together with various English and Czech translations of his works.

FleursDuMal.org Definitive online presentation of Fleurs du mal, featuring the original French alongside multiple English translations

_Select_ed works at Poetry Archive

Another _select_ion

The Rebel poem by Baudelaire

Les Foules (The Crowds) - English Translation

Translated by Cyril Scott. "The Flowers of Evil (1909)".

[1] Sean Bonney's experimental translations of Baudelaire (Humor)

References

^ Joanna Richardson, ‘’Baudelaire’’, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1994, pp. 13-14, ISBN 0-312-11476-1.

^ Richardson 1994, p.16

^ Richardson 1994, p.23

^ Richardson 1994, p.30, 32

^ Richardson 1994, p.35

^ Richardson 1994, p.42

^ Richardson 1994, p.46

^ Richardson 1994, p.52

^ Richardson 1994, pp. 55-57

^ Richardson 1994, p.60

^ Richardson 1994, pp. 67-68

^ Richardson 1994, p.70

^ Richardson 1994, p.71

^ Richardson 1994, p.75

^ Richardson 1994, p.83

^ Richardson 1994, p.95

^ Richardson 1994, pp. 101-102.

^ Richardson 1994, p.110.

^ Richardson 1994, p.127.

^ Richardson 1994, p.125.

^ Richardson 1994, p.160.

^ Richardson 1994, p.181.

^ Richardson 1994, p.219.

^ Richardson 1994, p.191.

^ Richardson 1994, p.236.

^ Richardson 1994, p.241.

^ Richardson 1994, p.231.

^ Richardson 1994, pp. 232-237.

^ Richardson 1994, p.238.

^ Richardson 1994, p.248

^ Richardson 1994, p.250.

^ Richardson 1994, p.250.

^ Richardson 1994, p.311.

^ Richardson 1994, p.281.

^ Richardson 1994, p. 400.

^ Richardson 1994, p.497.

^ Richardson 1994, p.268.

^ Richardson 1994, p.140.

^ Richardson 1994, p.110.

^ Lois Boe Hyslop, ‘’Baudelaire, Man Of His Time’’, Yale University Press, 1980, p.14, ISBN 0-300-02513-0.

^ Hyslop (1980), p. 68.

^ Hyslop (1980), p. 68.

^ Hyslop (1980), p. 69.

^ Hyslop (1980), p. 131.

^ Hyslop (1980), p. 55.

^ Hyslop (1980), p. 50.

^ Hyslop (1980), p. 53.

^ Hyslop (1980), p. 51.

^ Hyslop (1980), p. 65.

^ Hyslop (1980), p. 63.

^ Richardson 1994, p.50

^ Richardson 1994, p.50

^ Richardson 1994, p.50

^ Richardson 1994, p.50

^ Richardson 1994, p.116.

^ Richardson 1994, p.127.

^ Rimbaud, Arthur: Oeuvres complètes, p. 253, NRF/Gallimard, 1972.

^ 'Concerning Baudelaire' in Proust, Marcel: Against Sainte-Beuve and Other Essays, p. 286, trans. John Sturrock, Penguin, 1994.

^ Wilson, Edmund: Axel's Castle, p. 20, Fontana, 1962 (originally published 1931).

^ 'Baudelaire', in Eliot, T. S.: _Select_ed Essays, pp. 422 and 425, Faber & Faber, 1961.

^ cf. Eliot, 'Religion in Literature', in Eliot, op. cit., p.388.

^ 'The Task of the Translator', in Benjamin, Walter: _Select_ed Writings Vol. 1: 1913-1926, pp. 253-263, Belknap/Harvard, 1996.

^ Benjamin, Walter: The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin, Belknap/Harvard, 1999.

^ 'The Paris of the Second Empire in Baudelaire' in Benjamin, Walter: _Select_ed Writings Vol. 4 1938-1940, pp. 3-92, Belknap/Harvard, 2003.