| Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury | |

| 托馬斯·霍布斯 | |

|

閱讀霍布斯 Thomas Hobbes在百家争鸣的作品!!! | |

托馬斯·霍布斯(英語:Thomas Hobbes 1588年4月5日-1679年12月4日),是英國的政治哲學家,創立了機械唯物主義的完整體係,認為宇宙是所有機械地運動着的廣延物體的總和。他提出“自然狀態”和國傢起源說,認為國傢是人們為了遵守“自然法”而訂立契約所形成的,是一部人造的機器人,當君主可以履行該契約所約定的保證人民安全的職責時,人民應該對君主完全忠誠。他於1651年所出版的《利維坦》一書,為之後所有的西方政治哲學發展奠定根基。霍布斯的思想對其後的孟德斯鳩和讓-雅剋·盧梭有深刻影響,但同時,他的社會契約論與絶對君主製又有其獨特性。

雖然霍布斯最知名的是政治哲學的著作,但亦也有許多其他主題的著作,包括了歷史、幾何學、倫理學、和在現代被稱為政治學的哲學。除此之外,霍布斯認為人性的行為都是出於自私(self-centred)的,這也成為哲學人類學研究的重要理論。早年生涯和教育

霍布斯1588年4月5日生於英格蘭威爾特郡的馬姆斯伯裏 。他母親因聽聞西班牙無敵艦隊將入侵英格蘭的驚嚇而早産,日後霍布斯常說:我母親生了雙胞胎,我的孿生兄弟是恐懼。而他的一生也確實是在社會局勢動蕩不安恐懼氛圍中渡過的。 他父親因與不是自己小教區的牧師打鬥,被迫逃到倫敦,並將三名子女都寄托給他哥哥法蘭西斯照顧。霍布斯從四歲開始在馬姆斯伯裏的教堂接受教育,接着他前往私人學校就讀,由一名自牛津大學畢業的年輕人羅伯·拉蒂默教導。霍布斯是一名天賦極佳的學生,在大約1603年時他被送至牛津大學莫德林學院就讀。當時莫德林學院的校長是嚴格的清教徒John Wilkinson,年輕的霍布斯也受了他的影響。

在大學裏,霍布斯顯然依著自己的規劃學習;他很少被其他正規的學校課程所吸引。他直到1608年纔取得了學位,但在這段期間中他曾經由院長James Hussee爵士的推薦,擔任哈德威剋男爵卡文迪許之子威廉的家庭教師(亦即後來的德文郡公爵),霍布斯一生中和這一傢族的緊密關係也因此展開。

1610年霍布斯陪伴威廉在成年前的大旅遊遊遍歐洲大陸,因此有機會將他在牛津所接受的經院哲學教育與歐洲大陸具批判性的科學研究方式相比較。 這次大旅遊,不僅接觸到開普勒1609年出版的新天文學提出的行星橢圓形的運動軌跡日心說模型,同時,也讀到伽利略1610年3月出版的星際信使,記述了利用望遠鏡觀測到月球表面、金星的盈虧、木星的衛星、星座及銀河等細節制圖,使他的眼界大開。

回國後,威廉當選為議會的議員,霍布斯成了他的秘書,因而結識了英國詩人和劇作傢本·詹生(Ben Jonson,約1572年6月11日~1637年8月6日)及當時在詹姆斯一世繼位後仕途正走紅的法蘭西斯·培根。

1621年,培根因欠債及受賄,不準再從事公職,退隱從事著述,這段期間,霍布斯當他的秘書受到了培根哲學思想的啓發,這時霍布斯的興趣是文學,研究古希臘和拉丁文的著作。 1628年,議會起草權利請願書----沒有下議院的同意不可以徵稅、沒有正當的程序不可監禁人民、軍隊不可紮營在人民房捨及和平時期不可宣佈戒嚴。

霍布斯經過十餘年的努力,將修昔底德希臘文的伯羅奔尼撒戰爭史翻譯為英文,他有意的選在此時出版想要顯示民主政體諸種弊害,藉此表達對王室絶對權力的支持。 (註 : 他此時三十九歲,對利維坦的絶對君主權力的概念還未成形,還沒有自己圓融的哲學思想,衹是隱約不習慣下議院具有“草根性”新教議員的“民主運作方式”)

這本書翻譯的時程很長----也正好對比詹姆斯一世統治期間爆發1605年的火藥陰謀以及基層新教信仰的擴張,下議院的選出的新教代表的“草根性及鬥爭性”攪動了政治、社會上的秩序,1603年詹姆斯一世繼承英格蘭王位初期曾說:“下議院是具無腦的軀體。成員們以紊亂的舉止表達他們的意見;在他們的會議中除了哭聲、喊聲和混亂,什麽都聽不見。我感到驚訝的是我的祖先居然曾經允許這樣一個機構的存在”。 ( " The House of Commons is a body without a head. The members give their opinion in a disorderly manner; at their meetings nothing is heard but cries, shouts and confusion. I am surprised that my ancestors should ever have permitted such an institution to come into existence.")

霍布斯意識到希臘式的民主政府是有缺陷的,不僅無法贏得戰爭,也無法維持社會的穩定,他認為民主制度並不可取(註: 那時君權神授說是主流思想),“議會”衹是一個國王樞密院附屬的下級機構,“議會”的主要權力是在上議院,但是具備“草根性及鬥爭性”的“下議院”興起的趨勢正在成形。

雖然霍布斯曾擔任弗蘭西斯·培根的秘書,並和當時曾與一些文藝人士如本·瓊森交往甚密,但他在1629年之後纔開始擴展自己的哲學研究領域。他的贊助人—德文郡伯爵卡文迪許在1628年6月以三十五歲壯年據說因過度放縱(over-indulgence)去世,伯爵夫人不再雇請他。

不過霍布斯很快又找擔任喬維斯·剋利夫頓爵士(Gervase Clifton)之子的家庭教師。霍布斯為了這份工作一直到1631年卡文迪許傢族又再次雇請他,不過這次教導的對象改為威廉之子了。接下來七年裏霍布斯在教學的同時也不斷拓展自己的哲學知識,思考一些主要的哲學辯論問題。他在1636年前往佛羅倫斯旅行,並在巴黎加入了馬蘭·梅森等人的哲學辯論團體。

在巴黎

霍布斯最初有興趣的研究領域是物體的運動原理,儘管他對這一現象有高度興趣,但他卻不屑以物理學的實驗方式進行研究。他自行構想出了一套物理運行的原理,並且終身都在研究這套虛擬的原理。他首先寫下了幾篇論文闡述這套原理的架構,證明其原理在物理現象的運動上都是可以解釋的—至少在運動或機械運行上可以解釋。接着他將人類與自然界分隔開來,在另一篇論文裏顯示了哪些肉體的運動會牽涉到特殊的知覺現象、知識、和感情,以此證明人類的特殊之處。最後他在總結的論文裏闡述人類如何形成和參與社會,並主張社會應該避免人們退回“野蠻而不幸”的原始狀態。因此他主張肉體、人、和國傢這三者的現象應該要被一起研究。

霍布斯在1637年回到了祖國英國,當時英國的政治和社會局勢動蕩不安,霍布斯也無法再專心的進行哲學的研究了。不過,在他回到英國的最初幾年裏所寫下的論文集The Elements of Law裏,清楚顯示了當時他的政治思想還沒有被大幅改變,一直要到1640年代英國內戰爆發為止。

1640年11月,英國長期國會取代了短期國會,國會與國王間的衝突迅速惡化,霍布斯覺得他的著作可能會招致政治的迫害,因此很快便逃至巴黎,在接下來11年內都沒有再返回英國。在巴黎他重新加入了馬蘭·梅森的辯論團體,同時期他也寫下了一篇對於笛卡爾《形而上學的沉思》一書的批評。

他也逐漸回覆原先的研究工作,開始撰寫研究的第三部分De Cive,並在1641年11月撰寫完畢。雖然他最初衹打算私下傳閱,但這本書最後仍廣泛流傳。他接着重新著手研究的前兩個部分,將大部分時間都花在研究上,那幾年裏他除了一篇有關光學的短文(1644)外便很少發表其他作品。他在哲學界建立起了良好的名聲,並在1645年和笛卡爾等人一同被選出以調解有關化圓為方的學術爭議。

英國內戰

英國內戰在1642年爆發,當保王派的局面於1644年中旬開始惡化後,許多國王的支持者開始流亡歐洲。當中許多逃至巴黎的人都與霍布斯相識,這使得霍布斯開始對政治産生興趣,同時他的De Cive一書也重新發行並且廣泛留傳。

在1647年的一次偶然機會裏,霍布斯成為了威爾士親王查理斯的數學教師,當時查理斯正於7月左右前往澤西島旅行。兩人的師徒關係一直維持到1648年查理斯前往荷蘭為止。

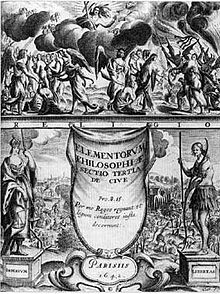

在許多流亡的英國保王派同鄉的影響下,霍布斯决定撰寫一本書以闡述政府的重要性、和政治混亂所造成的戰爭。全書架構是根基於1640年所寫的一篇未發表的論文上。在霍布斯看來,國傢就像一個偉大的巨人或怪物(利維坦)一般,它的身體由所有的人民所組成,它的生命則起源於人們對於一個公民政府的需求,否則社會便會陷入因人性求生本能而不斷動亂的原始狀態。全書以一篇“回顧與總結”作終,霍布斯總結道人民無論如何都不能違背與國傢簽下的社會契約,然而,霍布斯也討論到了當利維坦無法再保護其人民時,這個社會契約便會等於無效。由於當時英國的局勢縱容對於宗教教條的批判,霍布斯的理論也因此更無所忌諱。利維坦的初版名為Elementa philosophica de cive。

在撰寫利維坦的期間霍布斯一直留在巴黎。1647年霍布斯染上了一場大病,使他臥倒在床長達6個月。在病況恢復後他又再度開始撰寫,並保持穩定的進度直到將近1650年纔完成全書,同時也將許多他之前的拉丁文作品翻譯至英文。1650年,在等待利維坦出版的期間,他允許出版商將許多他早期的論文分為兩本小册子出版。在1651年他又出版了他所翻譯的De Cive。利維坦的印刷工作花費了不少時間,最後終於在1651年中旬上市,當時的書名是《利維坦,或教會國傢和市民國傢的實質、形式和權力》,初版的封面捲頭插畫(見下圖)也非常知名,描繪出一個戴着王冠的利維坦巨人,一手持劍、一手持仗,巨人的身體則由無數的人民所構成。

這本書剛出版便造成了轟動。很快的霍布斯便接到了大量的贊美和批評,遠遠超出當時所有其他的思想傢。不過,這本書的出版卻迅速使他與其他逃亡的保王派關係决裂,迫使他不得不嚮革命派的英國政府求取保護。當時保王派試圖殺掉他,因為書中的現實主義內容不但震怒了信仰聖公會的保王派、也震怒了信仰天主教的法國人。霍布斯逃回了英國,在1651年鼕天抵達倫敦。在他嚮革命派政府表示歸順後,他被允許在倫敦的福特巷過着隱居的生活。

利維坦

《利維坦》(Leviathan)一書寫於英國內戰進行之時。此書分為三部分,霍布斯藉此闡述了他對個人、社會、政府、法律和宗教等的理論,並重點論述了他關於社會基礎與政府合法性的看法。在第一部分中,霍布斯闡述了他的唯物論的哲學觀,為後兩部的展開做了理論準備。第二部分為他的政府和法律論,也是他著作最為後人看重的部分。第三部分主要是宗教論,否定了羅馬教會的統治,認為國傢有權幹預教會。

霍布斯認為人在自然狀態中是侵略者,基於這個推理,政府要強大,法律要嚴格,執行要有力,這樣才能避免人狼性的爆發。

《利維坦》內容概覽

第1-5章:人體運作機製:表達唯物主義自然觀和一般的哲學觀點,說明宇宙是由物質的微粒構成,物體是獨立的客觀存在,物質永恆存在,既非人所創造,也非人所能消滅,一切物質都於運動狀態中

第6章:欲望和恐懼:人們通過權衡欲望和恐懼做出自主選擇

第7-11章:人與群體:人類如果在群體之中以及對他人的不同表現所采取的反應

第12-16章:國傢的建立:出於人的理性,人們相互間同意訂立契約,放棄各人的自然權利,把它托付給某一個人或一個由多人組成的集體,這個人或集體能把大傢的意志化為一個意志,能把大傢的人格統一為一個人格;大傢則服從他的意志,服從他的判斷

第17-31章:政府權力,統治和人民

第31章始:論基督教國傢與論黑暗王國(指羅馬教會)

人類的自然狀態下,有一些人可能比別人更強壯或更聰明,但沒有一個會強壯到或聰明到不怕在暴力下死亡。當受到死亡威脅時,在自然狀態下的人必然會盡一切所能來保護他自己。霍布斯認為保護自己免於暴力死亡就是人類最高的需要,而權力就是來自於這種需要。在霍布斯所描述的“自然狀態”(state of nature)下,每個人都需要世界上的每樣東西,也就有對每樣東西的權力。但由於世界上的東西都是不足的,所以這種爭奪權力的“所有人對所有人的戰爭”(every man is enemy to every man)便永遠不會結束。而人生在這種自然狀態下便是“孤獨、貧睏、污穢、野蠻又短暫的”(solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short)(xiii)。

但戰爭並不是對人最有利的。霍布斯認為人考慮自身安全和免被他人侵犯而渴望結束戰爭——“使人傾嚮於和平的熱忱其實是怕死,以及對於舒適生活之必要東西的欲求和殷勤獲取這些東西的盼望”(xiii, 14)。霍布斯認為社會若要和平就必需要有社會契約(Social contract)。霍布斯認為社會是一群人服從於一個人(Single-ruler form)的威權之下,而每個個人(individual)將自然權力交付給這威權,讓它來維持內部的和平、並抵抗外來的敵人。這個主權,無論是君主製(Monarchy)、貴族製(Aristocracy)或民主製(Democracy)(霍布斯較傾嚮君主製),都必須是一個強而有威信的“利維坦”,即在一個絶對的威權之下,方能令社會契約實行。對霍布斯而言,法律的作用就是要確保契約的執行。

利維坦國傢在防止侵略、發動戰爭對抗他人、或是任何有關保持國傢和平方面的事務上是有無限威權的。至於其他方面,國傢是完全不管的。衹要一個人不去傷害別人,國傢主權是不會去干涉他的(不過,由於在國傢主權之上並沒有任何更高的權力,沒有人可以防止國傢破壞這規則)。在事實上,這種主權的行使程度是以主權對自然法的責任為限的。雖然主權並沒有立法的責任,但它也有義務遵守那些指定了和平界綫的法律(自然法, the law of nature),也因此這種限製使得主權的權威必須遵守一種道德責任。一個主權也必須保持國內的平等,因為普通人民都會被主權的光輝所掩蓋;霍布斯將這種光輝與太陽的陽光相比,既然陽光耀眼無比,普通人也會因此褪色。在本質上,霍布斯的政治原則是“不要傷害”,他的道德黃金律是“己所不欲,勿施於人”(xv, 35)。也是從這裏霍布斯的道德觀與一般基督教的黃金律“己所欲,施於人”産生差異,霍布斯認為那衹會造成社會混亂罷了。

利維坦寫於英國內戰期間,書裏的大多數篇幅都用於證明強大的中央權威才能夠避免邪惡的混亂和內戰。任何對此權威的濫用都會造成對和平的破壞。霍布斯也否定了權力分立的理想:他認為主權必須有全盤控製公民、軍事、司法、和教會的權力。在利維坦中,霍布斯明確的指出主權擁有改變人民信仰和理念的權威,如果人民不這樣做便會引起混亂。他本人即宣稱願意服從主權的命令改變信仰。

在英文裏,有時候人們會以“霍布斯主義”(Hobbesian)一詞來形容一種無限製的、自私、而野蠻的競爭情況,不過這種用法其實是錯誤的:首先,《利維坦》裏描繪出了這種情況、但僅僅是為了批判之;第二,霍布斯本人其實是相當膽小而書呆子氣的。此外,在利維坦出版後,霍布斯也經常被人用以形容無神論以及“強權就是公理”的觀念,儘管這些都不是霍布斯的初衷。

爭論

與布蘭豪

在回到英國之後,霍布斯重新開始進行他的哲學原理研究。他在1654年出版了De Corpore,同年也發表了一篇短論文Of Liberty and Necessity,由一名與霍布斯熟識的主教約翰·布蘭豪(John Bramhall)出版。布蘭豪是一名忠誠的阿米紐教派信徒,他在認識霍布斯之後便經常與之辯論,兩人以書信私下往來的方式進行辯論和交換意見,不過霍布斯並沒有公開這些信函。後來一名霍布斯的法國友人偶然間發現了一封霍布斯回信的抄本,便將其公開出版並附上“豪華的贊美言詞”。布蘭豪對此相當不滿,於是在1655年將所有兩人來往的書信都公諸於世(以A Defence of the True Liberty of Human Actions from Antecedent or Extrinsic Necessity為標題出版)。接着霍布斯在1656年寫下了“論點石破天驚”的Questions concerning Liberty, Necessity and Chance回覆主教,這封信或許是第一篇詳細闡述了决定論的心理學原則的文件,霍布斯的理論也成為了自由意志爭論的歷史中重要的一部分。主教在1658年以一篇Castigations of Mr Hobbes's Animadversions回覆,不過霍布斯並沒有註意到這份回覆。

與沃利斯

除了與布蘭豪的爭論外,霍布斯自從於1655年出版De Corpore開始也與其他學者産生不少衝突。在《利維坦》中他挑戰了當時的學術界。在1654年,牛津大學的天文學教授塞思·沃德(Seth Ward)在一篇名為Vindiciae academiarum的文章中回覆了霍布斯對於學術界的挑戰。霍布斯在De Corpore哲學原理中的許多錯誤—尤其是在數學上的錯誤也招致了幾何學教授約翰·沃利斯的批評。沃利斯在1655年出版的Elenchus geomeiriae Hobbianae中詳細解釋了霍布斯哲學原理的錯誤,他批評霍布斯以邏輯推理的方式作為數學演算的主軸,並揭露了霍布斯在數學上的許多漏洞。由於霍布斯在演算上缺乏精確的計算,造成他經常使用證據不足的假設來解决原理的問題,由於他的興趣衹限於幾何學上,因此他對於數學的整體領域並沒有很清楚的概念。這些問題都使得霍布斯的哲學原理大受批評。最後霍布斯在1656年發行英文版本的De Corpore時便刪除了一些被沃利斯揭發的嚴重錯誤,但他仍然在1656年的Six Lessons to the Professors of Mathematics一係列文章裏反駁沃利斯的批評。沃利斯接着寫了一篇論文反駁霍布斯的論點,並趁著霍布斯發行De Corpore英文譯本的期間繼續批評他在數學上的錯誤,霍布斯則以數篇論文反擊。但沃利斯輕易的以一篇回覆(Hobbiani puncti dispunctio, 1657)擊倒霍布斯的論點。最後霍布斯拒絶再回覆沃利斯,兩人的爭論暫時停息。

霍布斯在1658年發表了他的哲學原理的最後一個部分,將他已經計劃二十年之久的整套原理加以總結。他在De Homine一書裏闡述了整套原理的運作,這套哲學原理也與他在政治哲學上的主張相連。同時期沃利斯則發表了微積分的一般原理(Mathesis universatis, 1657)。這時研究工作已經告一段落的霍布斯决定再度挑起爭論,他在1660年春季再度發起攻勢,將六篇論文以Examinatio et emendatio mathematicae hodiernae qualis explicatur in libris Johannis Wallisii為標體出版,批評當時新的數學分析方式。不過這次沃利斯並沒有上當,選擇沉默以對。霍布斯接着試着提起另一個古老的數學問題—加倍立方體問題(Doubling the cube),他私下從法國一位匿名人士信中得知了問題的解答,試圖以這個問題混淆他的批評者。但很快的沃利斯便公開的駁倒了這個解答。霍布斯在1661年底重新以拉丁文出版了這一係列論文(並稍微修改之)並加上替自己辯護文章,在這本名為Dialogus physicus, sive De natura aeris的書中霍布斯還攻擊了羅伯特·波義耳及其他沃利斯的朋友。這次霍布斯改變一貫論調,主張波義耳等人的實驗紀錄—1660年的New Experiments touching the Spring of the Air衹不過是證實了他早年提出的推測理論,他並且警告這些新生代的“學者”必須接手他早年未完成的研究進度,否則既有的實驗結果便會毫無進展。然而波義耳等人很輕易的便駁倒了這種站不住腳的批評,緊接着沃利斯寫了一篇名為Hobbius heauton-timorumenos(1662)的諷刺作品來挖苦霍布斯。在這次慘痛教訓之後霍布斯便不再參與科學界的爭論了。 ...

幾何學

在經過一段時間的沉寂後,霍布斯又開始了他人生中第三階段的爭議行動,並且一直維持至他九十歲為止。第一份引發爭議的文章是在1666年發表的De principiis et ratiocinatione geometrarum,霍布斯以此攻擊當時的幾何學界教授。三年之後他將他的三篇數學論文集中於Quadratura circuli, Cubatio sphaerae, Duplicitio cubii發表,很快的這些文章再度被沃利斯駁倒,但霍布斯仍不放棄,又出版了回應批評的版本,但沃利斯仍在當年年底再次駁倒新的版本。這一係列的爭論一直要維持至1678年為止。

晚年

除了出版大量論述欠佳而又飽受批評的數學和幾何學著作之外,霍布斯也繼續撰寫並出版哲學的著作。在1660年英國王政復闢後,“霍布斯主義”這一詞開始被用於稱呼那些“反對熱愛道德和信仰”的態度。剛復闢的年輕國王查理斯二世幼年時曾經是霍布斯的弟子,在他想起霍布斯後,他將霍布斯召至王宮並賞賜他£100的退休金。

在1666年,英國下議院通過了一項對所有無神論者和“不敬神者”不利的法案,這時查理斯國王再次保護了霍布斯免受迫害。當時霍布斯的《利維坦》被視為是無神論和褻瀆的代表作,霍布斯很擔心會被貼上異教徒的標簽,於是他燒掉了許多可能會對自己不利的文稿。這次危機也使霍布斯開始檢視異端的真相,他將研究結果集合於三篇簡短的論文上,並將其收錄至拉丁文版《利維坦》的附錄中,於1668年在阿姆斯特丹出版。在這幾篇論文中霍布斯指出,除了違反尼西亞信經以外其他的理論都不能被視為異端,並且主張《利維坦》一書仍然符合尼西亞信經的原則。近年來,《利維坦》的拉丁文版益受學者重視,因為其中保存了一些霍布斯晚年對其早期理論的發展和補充。

由於國王的保護,下議院通過的法案最後並沒有對霍布斯造成太大傷害,不過霍布斯從此不能在英格蘭發表任何有關人類行為的著作了。他在1688年的著作由於無法通過英格蘭的出版品審查機構,衹得改在阿姆斯特丹出版。其他的許多著作則要直到他死後纔得以出版。有時候霍布斯甚至被禁止回覆他在學術辯論中遭受的批評。儘管如此,霍布斯在國外的名聲非常高,當時前往英格蘭旅遊的學者和名人都會抽空拜訪霍布斯,嚮這位老哲學家表達敬意。

霍布斯最後的作品是在1672年出版的一篇拉丁文自傳,同時他還將奧德賽翻譯為四本“粗劣的”英文譯本,並在1675年完成了整套奧德賽和伊利亞特的翻譯。

霍布斯在1679年染上了膀胱疾病,並且死於接踵而來的中風發作,享年九十一歲。他被葬在德貝郡一座教堂的墓地裏。

重要著作

- 1629. 翻譯修昔底德的《伯羅奔尼撒戰爭史》

- 1650. The Elements of Law, Natural and Political, 寫於1640年

- Human Nature, or the Fundamental Elements of Policie

- De Corpore Politico

- 1651-8. Elementa philosophica

- 1642. De Cive (拉丁文)

- 1651. Philosophical Rudiments concerning Government and Society (De Cive的英文譯本)

- 1655. De Corpore (拉丁文)

- 1656. De Corpore (英文翻譯)

- 1658. De Homine (拉丁文)

- 1651. 利維坦,或教會國傢和市民國傢的實質、形式和權力. Online.

- 1656. Questions concerning Liberty, Necessity and Chance

- 1668. 利維坦的拉丁文翻譯

- 1675. 翻譯荷馬的奧德賽和伊利亞特為英文

- 1681. 死後出版的Behemoth, or The Long Parliament (寫於1668年)。

參考文獻

- Macpherson, C. B. (1962). The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism: Hobbes to Locke. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Martinich A.P. (1995). A Hobbes Dictionary (Blackwell Philosopher Dictionaries). Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-19262-X & ISBN 0-631-19261-1

- Robinson, Dave & Groves, Judy (2003). Introducing Political Philosophy. Icon Books. ISBN 1-84046-450-X.

- Strauss, Leo (1936). The Political Philosophy of Hobbes; Its Basis and Its Genesis. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Strauss, Leo (1959). "On the Basis of Hobbes's Political Philosophy," in What Is Political Philosophy?, Glencoe, Ill.: The Free Press, chap. 7.

Biography

Early life

Thomas Hobbes was born on 5 April 1588, in Westport, now part of Malmesbury in Wiltshire, England. Having been born prematurely when his mother heard of the coming invasion of the Spanish Armada, Hobbes later reported that "my mother gave birth to twins: myself and fear." Hobbes had a brother, Edmund, about two years older, as well as a sister.

Although Thomas Hobbes' childhood is unknown to a large extent, as is his mother's name, it is known that Hobbes' father, Thomas Sr., was the vicar of both Charlton and Westport. Hobbes' father was uneducated, according to John Aubrey, Hobbes' biographer, and he "disesteemed learning." Thomas Sr. was involved in a fight with the local clergy outside his church, forcing him to leave London. As result, the family was left in the care of Thomas Sr.'s older brother, Francis, a wealthy glove manufacturer with no family of his own.

Education

Hobbes Jr. was educated at Westport church from age four, passed to the Malmesbury school, and then to a private school kept by a young man named Robert Latimer, a graduate of the University of Oxford. Hobbes was a good pupil, and between 1601 and 1602 he went up to Magdalen Hall, the predecessor to Hertford College, Oxford, where he was taught scholastic logic and physics. The principal, John Wilkinson, was a Puritan and had some influence on Hobbes. Before going up to Oxford, Hobbes translated Euripides' Medea from Greek into Latin verse.

At university, Thomas Hobbes appears to have followed his own curriculum as he was little attracted by the scholastic learning. Leaving Oxford, Hobbes completed his B.A. degree by incorporation at St John's College, Cambridge in 1608. He was recommended by Sir James Hussey, his master at Magdalen, as tutor to William, the son of William Cavendish, Baron of Hardwick (and later Earl of Devonshire), and began a lifelong connection with that family. William Cavendish was elevated to the peerage on his father's death in 1626, holding it for two years before his death in 1628. His son, also William, likewise became the 3rd Earl of Devonshire. Hobbes served as a tutor and secretary to both men. The 1st Earl's younger brother, Charles Cavendish, had two sons who were patrons of Hobbes. The elder son, William Cavendish, later 1st Duke of Newcastle, was a leading supporter of Charles I during the civil war personally financing an army for the king, having been governor to the Prince of Wales, Charles James, Duke of Cornwall. It was to this William Cavendish that Hobbes dedicated his Elements of Law.

Hobbes became a companion to the younger William and they both took part in a grand tour of Europe between 1610 and 1615. Hobbes was exposed to European scientific and critical methods during the tour, in contrast to the scholastic philosophy that he had learned in Oxford. In Venice, Hobbes made the acquaintance of Fulgenzio Micanzio, an associate of Paolo Sarpi, a Venetian scholar and statesman.

His scholarly efforts at the time were aimed at a careful study of classic Greek and Latin authors, the outcome of which was, in 1628, his great translation of Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War, the first translation of that work into English from a Greek manuscript.It has been argued that three of the discourses in the 1620 publication known as Horea Subsecivae: Observations and Discourses also represent the work of Hobbes from this period.

Although he did associated with literary figures like Ben Jonson and briefly worked as Francis Bacon's amanuensis, translating several of his Essays into Latin, he did not extend his efforts into philosophy until after 1629. In June 1628, his employer Cavendish, then the Earl of Devonshire, died of the plague, and his widow, the countess Christian, dismissed Hobbes.

In Paris (1630–1637)

Hobbes soon found work as a tutor to Gervase Clifton, the son of Sir Gervase Clifton, 1st Baronet mostly spent in Paris until 1631. Thereafter, he again found work with the Cavendish family, tutoring William Cavendish, 3rd Earl of Devonshire, the eldest son of his previous pupil. Over the next seven years, as well as tutoring, he expanded his own knowledge of philosophy, awakening in him curiosity over key philosophic debates. He visited Galileo Galilei in Florence while he was under house arrest upon condemnation, in 1636, and was later a regular debater in philosophic groups in Paris, held together by Marin Mersenne.

Hobbes's first area of study was an interest in the physical doctrine of motion and physical momentum. Despite his interest in this phenomenon, he disdained experimental work as in physics. He went on to conceive the system of thought to the elaboration of which he would devote his life. His scheme was first to work out, in a separate treatise, a systematic doctrine of body, showing how physical phenomena were universally explicable in terms of motion, at least as motion or mechanical action was then understood. He then singled out Man from the realm of Nature and plants. Then, in another treatise, he showed what specific bodily motions were involved in the production of the peculiar phenomena of sensation, knowledge, affections and passions whereby Man came into relation with Man. Finally, he considered, in his crowning treatise, how Men were moved to enter into society, and argued how this must be regulated if people were not to fall back into "brutishness and misery". Thus he proposed to unite the separate phenomena of Body, Man, and the State.

In England (1637–1641)

Hobbes came back home, in 1637, to a country riven with discontent, which disrupted him from the orderly execution of his philosophic plan. However, by the end of the Short Parliament in 1640, he had written a short treatise called The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic. It was not published and only circulated as a manuscript among his acquaintances. A pirated version, however, was published about ten years later. Although it seems that much of The Elements of Law was composed before the sitting of the Short Parliament, there are polemical pieces of the work that clearly mark the influences of the rising political crisis. Nevertheless, many (though not all) elements of Hobbes's political thought were unchanged between The Elements of Law and Leviathan, which demonstrates that the events of the English Civil War had little effect on his contractarian methodology. However, the arguments in Leviathan were modified from The Elements of Law when it came to the necessity of consent in creating political obligation: Hobbes wrote in The Elements of Law that Patrimonial kingdoms were not necessarily formed by the consent of the governed, while in Leviathan he argued that they were. This was perhaps a reflection either of Hobbes's thoughts about the engagement controversy or of his reaction to treatises published by Patriarchalists, such as Sir Robert Filmer, between 1640 and 1651.[citation needed]

When in November 1640 the Long Parliament succeeded the Short, Hobbes felt that he was in disfavour due to the circulation of his treatise and fled to Paris. He did not return for 11 years. In Paris, he rejoined the coterie around Mersenne and wrote a critique of the Meditations on First Philosophy of Descartes, which was printed as third among the sets of "Objections" appended, with "Replies" from Descartes, in 1641. A different set of remarks on other works by Descartes succeeded only in ending all correspondence between the two.

Hobbes also extended his own works in a way, working on the third section, De Cive, which was finished in November 1641. Although it was initially only circulated privately, it was well received, and included lines of argumentation that were repeated a decade later in Leviathan. He then returned to hard work on the first two sections of his work and published little except a short treatise on optics (Tractatus opticus) included in the collection of scientific tracts published by Mersenne as Cogitata physico-mathematica in 1644. He built a good reputation in philosophic circles and in 1645 was chosen with Descartes, Gilles de Roberval and others to referee the controversy between John Pell and Longomontanus over the problem of squaring the circle.

Civil War Period (1642–1651)

The English Civil War began in 1642, and when the royalist cause began to decline in mid-1644, many royalists came to Paris and were known to Hobbes. This revitalised Hobbes's political interests and the De Cive was republished and more widely distributed. The printing began in 1646 by Samuel de Sorbiere through the Elsevier press in Amsterdam with a new preface and some new notes in reply to objections.

In 1647, Hobbes took up a position as mathematical instructor to the young Charles, Prince of Wales, who had come to Paris from Jersey around July. This engagement lasted until 1648 when Charles went to Holland.

The company of the exiled royalists led Hobbes to produce Leviathan, which set forth his theory of civil government in relation to the political crisis resulting from the war. Hobbes compared the State to a monster (leviathan) composed of men, created under pressure of human needs and dissolved by civil strife due to human passions. The work closed with a general "Review and Conclusion", in response to the war, which answered the question: Does a subject have the right to change allegiance when a former sovereign's power to protect is irrevocably lost?

During the years of composing Leviathan, Hobbes remained in or near Paris. In 1647, a serious illness that nearly killed him disabled him for six months. On recovering, he resumed his literary task and completed it by 1650. Meanwhile, a translation of De Cive was being produced; scholars disagree about whether it was Hobbes who translated it.

In 1650, a pirated edition of The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic was published. It was divided into two small volumes: Human Nature, or the Fundamental Elements of Policie; and De corpore politico, or the Elements of Law, Moral and Politick.

In 1651, the translation of De Cive was published under the title Philosophicall Rudiments concerning Government and Society. Also, the printing of the greater work proceeded, and finally appeared in mid-1651, titled Leviathan, or the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Common Wealth, Ecclesiasticall and Civil. It had a famous title-page engraving depicting a crowned giant above the waist towering above hills overlooking a landscape, holding a sword and a crozier and made up of tiny human figures. The work had immediate impact. Soon, Hobbes was more lauded and decried than any other thinker of his time. The first effect of its publication was to sever his link with the exiled royalists, who might well have killed him. The secularist spirit of his book greatly angered both Anglicans and French Catholics. Hobbes appealed to the revolutionary English government for protection and fled back to London in winter 1651. After his submission to the Council of State, he was allowed to subside into private life in Fetter Lane.[citation needed]

Later life

In 1658, Hobbes published the final section of his philosophical system, completing the scheme he had planned more than 20 years before. De Homine consisted for the most part of an elaborate theory of vision. The remainder of the treatise dealt cursorily with some of the topics more fully treated in the Human Nature and the Leviathan. In addition to publishing some controversial writings on mathematics and physics, Hobbes also continued to produce philosophical works.

From the time of the Restoration, he acquired a new prominence; "Hobbism" became a byword for all that respectable society ought to denounce. The young king, Hobbes' former pupil, now Charles II, remembered Hobbes and called him to the court to grant him a pension of £100.

The king was important in protecting Hobbes when, in 1666, the House of Commons introduced a bill against atheism and profaneness. That same year, on 17 October 1666, it was ordered that the committee to which the bill was referred "should be empowered to receive information touching such books as tend to atheism, blasphemy and profaneness... in particular... the book of Mr. Hobbes called the Leviathan." Hobbes was terrified at the prospect of being labelled a heretic, and proceeded to burn some of his compromising papers. At the same time, he examined the actual state of the law of heresy. The results of his investigation were first announced in three short Dialogues added as an Appendix to his Latin translation of Leviathan, published in Amsterdam in 1668. In this appendix, Hobbes aimed to show that, since the High Court of Commission had been put down, there remained no court of heresy at all to which he was amenable, and that nothing could be heresy except opposing the Nicene Creed, which, he maintained, Leviathan did not do.

The only consequence that came of the bill was that Hobbes could never thereafter publish anything in England on subjects relating to human conduct. The 1668 edition of his works was printed in Amsterdam because he could not obtain the censor's licence for its publication in England. Other writings were not made public until after his death, including Behemoth: the History of the Causes of the Civil Wars of England and of the Counsels and Artifices by which they were carried on from the year 1640 to the year 1662. For some time, Hobbes was not even allowed to respond, whatever his enemies tried. Despite this, his reputation abroad was formidable.

His final works were an autobiography in Latin verse in 1672, and a translation of four books of the Odyssey into "rugged" English rhymes that in 1673 led to a complete translation of both Iliad and Odyssey in 1675.

Death

In October 1679 Hobbes suffered a bladder disorder, and then a paralytic stroke, from which he died on 4 December 1679, aged 91. His last words were said to have been "A great leap in the dark", uttered in his final conscious moments. His body was interred in St John the Baptist's Church, Ault Hucknall, in Derbyshire.

Political theory

Hobbes, influenced by contemporary scientific ideas, had intended for his political theory to be a quasi-geometrical system, in which the conclusions followed inevitably from the premises. The main practical conclusion of Hobbes' political theory is that state or society cannot be secure unless at the disposal of an absolute sovereign. From this follows the view that no individual can hold rights of property against the sovereign, and that the sovereign may therefore take the goods of its subjects without their consent. This particular view owes its significance to it being first developed in the 1630s when Charles I had sought to raise revenues without the consent of Parliament, and therefore of his subjects.

Leviathan

In Leviathan, Hobbes set out his doctrine of the foundation of states and legitimate governments and creating an objective science of morality.[citation needed] Much of the book is occupied with demonstrating the necessity of a strong central authority to avoid the evil of discord and civil war.

Beginning from a mechanistic understanding of human beings and their passions, Hobbes postulates what life would be like without government, a condition which he calls the state of nature. In that state, each person would have a right, or license, to everything in the world. This, Hobbes argues, would lead to a "war of all against all" (bellum omnium contra omnes). The description contains what has been called one of the best-known passages in English philosophy, which describes the natural state humankind would be in, were it not for political community:

In such states, people fear death and lack both the things necessary to commodious living, and the hope of being able to obtain them. So, in order to avoid it, people accede to a social contract and establish a civil society. According to Hobbes, society is a population and a sovereign authority, to whom all individuals in that society cede some right for the sake of protection. Power exercised by this authority cannot be resisted, because the protector's sovereign power derives from individuals' surrendering their own sovereign power for protection. The individuals are thereby the authors of all decisions made by the sovereign, "he that complaineth of injury from his sovereign complaineth that whereof he himself is the author, and therefore ought not to accuse any man but himself, no nor himself of injury because to do injury to one's self is impossible". There is no doctrine of separation of powers in Hobbes's discussion. According to Hobbes, the sovereign must control civil, military, judicial and ecclesiastical powers, even the words.

Opposition

John Bramhall

In 1654 a small treatise, Of Liberty and Necessity, directed at Hobbes, was published by Bishop John Bramhall. Bramhall, a strong Arminian, had met and debated with Hobbes and afterwards wrote down his views and sent them privately to be answered in this form by Hobbes. Hobbes duly replied, but not for publication. However, a French acquaintance took a copy of the reply and published it with "an extravagantly laudatory epistle". Bramhall countered in 1655, when he printed everything that had passed between them (under the title of A Defence of the True Liberty of Human Actions from Antecedent or Extrinsic Necessity).

In 1656, Hobbes was ready with The Questions concerning Liberty, Necessity and Chance, in which he replied "with astonishing force" to the bishop. As perhaps the first clear exposition of the psychological doctrine of determinism, Hobbes's own two pieces were important in the history of the free-will controversy. The bishop returned to the charge in 1658 with Castigations of Mr Hobbes's Animadversions, and also included a bulky appendix entitled The Catching of Leviathan the Great Whale.

John Wallis

Hobbes opposed the existing academic arrangements, and assailed the system of the original universities in Leviathan. He went on to publish De Corpore, which contained not only tendentious views on mathematics but also an erroneous proof of the squaring of the circle. This all led mathematicians to target him for polemics and sparked John Wallis to become one of his most persistent opponents. From 1655, the publishing date of De Corpore, Hobbes and Wallis went round after round trying to disprove each other's positions. After years of debate, the spat over proving the squaring of the circle gained such notoriety that it has become one of the most infamous feuds in mathematical history.

Religious views

Hobbes was accused of atheism by several contemporaries; Bramhall accused him of teachings that could lead to atheism. This was an important accusation, and Hobbes himself wrote, in his answer to Bramhall's The Catching of Leviathan, that "atheism, impiety, and the like are words of the greatest defamation possible". Hobbes always defended himself from such accusations. In more recent times also, much has been made of his religious views by scholars such as Richard Tuck and J. G. A. Pocock, but there is still widespread disagreement about the exact significance of Hobbes's unusual views on religion.

As Martinich has pointed out, in Hobbes's time the term "atheist" was often applied to people who believed in God but not in divine providence, or to people who believed in God but also maintained other beliefs that were inconsistent with such belief. He says that this "sort of discrepancy has led to many errors in determining who was an atheist in the early modern period". In this extended early modern sense of atheism, Hobbes did take positions that strongly disagreed with church teachings of his time. For example, he argued repeatedly that there are no incorporeal substances, and that all things, including human thoughts, and even God, heaven, and hell are corporeal, matter in motion. He argued that "though Scripture acknowledge spirits, yet doth it nowhere say, that they are incorporeal, meaning thereby without dimensions and quantity". (In this view, Hobbes claimed to be following Tertullian.) Like John Locke, he also stated that true revelation can never disagree with human reason and experience, although he also argued that people should accept revelation and its interpretations for the reason that they should accept the commands of their sovereign, in order to avoid war.

While in Venice on tour, Hobbes made the acquaintance of Fulgenzio Micanzio, a close associate of Paolo Sarpi, who had written against the pretensions of the papacy to temporal power in response to the Interdict of Pope Paul V against Venice, which refused to recognise papal prerogatives. James I had invited both men to England in 1612. Micanzio and Sarpi had argued that God willed human nature, and that human nature indicated the autonomy of the state in temporal affairs. When he returned to England in 1615, William Cavendish maintained correspondence with Micanzio and Sarpi, and Hobbes translated the latter's letters from Italian, which were circulated among the Duke's circle.

Works (bibliography)

- 1602. Latin translation of Euripides' Medea (lost).

- 1620. "A Discourse of Tacitus", "A Discourse of Rome", and "A Discourse of Laws." In The Horae Subsecivae: Observation and Discourses.

- 1626. "De Mirabilis Pecci, Being the Wonders of the Peak in Darby-shire" (publ. 1636) — a poem on the Seven Wonders of the Peak

- 1629. Eight Books of the Peloponnesian Warre, translation with an Introduction of Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War

- 1630. A Short Tract on First Principles.

- Authorship doubtful, as this work is attributed by some critics to Robert Payne.

- 1637. A Briefe of the Art of Rhetorique

- Molesworth edition title: The Whole Art of Rhetoric.

- Authorship probable: While Schuhmann (1998) firmly rejects the attribution of this work to Hobbes, a preponderance of scholarship disagrees with Schuhmann's idiosyncratic assessment. Schuhmann disagrees with historian Quentin Skinner, who would come to agree with Schuhmann.

- 1639. Tractatus opticus II

- 1640. Elements of Law, Natural and Politic

- Initially circulated only in handwritten copies; without Hobbes's permission, the first printed edition would be in 1650.

- 1641. Objectiones ad Cartesii Meditationes de Prima Philosophia — 3rd series of Objections

- 1642. Elementorum Philosophiae Sectio Tertia de Cive (Latin, 1st limited ed.).

- 1643. De Motu, Loco et Tempore

- First edition (1973) title: Thomas White's De Mundo Examined

- 1644. Part of the "Praefatio to Mersenni Ballistica." In F. Marini Mersenni minimi Cogitata physico-mathematica. In quibus tam naturae quàm artis effectus admirandi certissimis demonstrationibus explicantur.

- 1644. "Opticae, liber septimus" (written in 1640). In Universae geometriae mixtaeque mathematicae synopsis, edited by Marin Mersenne.

- Molesworth edition (OL V, pp. 215–48) title: "Tractatus Opticus"

- 1646. A Minute or First Draught of the Optiques

- Molesworth published only the dedication to Cavendish and the conclusion in EW VII, pp. 467–71.

- 1646. Of Liberty and Necessity (publ. 1654)

- Published without the permission of Hobbes

- 1647. Elementa Philosophica de Cive

- Second expanded edition with a new Preface to the Reader

- 1650. Answer to Sir William Davenant's Preface before Gondibert

- 1650. Human Nature: or The fundamental Elements of Policie

- Includes first thirteen chapters of The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic

- Published without Hobbes's authorisation

- 1650. The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic (pirated ed.)

- Repackaged to include two parts:

- "Human Nature, or the Fundamental Elements of Policie," ch. 14–19 of Elements, Part One (1640)

- "De Corpore Politico", Elements, Part Two (1640)

- Repackaged to include two parts:

- 1651. Philosophicall Rudiments concerning Government and Society — English translation of De Cive

- 1651. Leviathan, or the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Commonwealth, Ecclesiasticall and Civil

- 1654. Of Libertie and Necessitie, a Treatise

- 1655. De Corpore (in Latin)

- 1656. Elements of Philosophy, The First Section, Concerning Body — anonymous English translation of De Corpore

- 1656. Six Lessons to the Professor of Mathematics

- 1656. The Questions concerning Liberty, Necessity and Chance — reprint of Of Libertie and Necessitie, a Treatise, with the addition of Bramhall's reply and Hobbes's reply to Bramahall's reply.

- 1657. Stigmai, or Marks of the Absurd Geometry, Rural Language, Scottish Church Politics, and Barbarisms of John Wallis

- 1658. Elementorum Philosophiae Sectio Secunda De Homine

- 1660. Examinatio et emendatio mathematicae hodiernae qualis explicatur in libris Johannis Wallisii

- 1661. Dialogus physicus, sive De natura aeris

- 1662. Problematica Physica

- English translation (1682) title: Seven Philosophical Problems

- 1662. Seven Philosophical Problems, and Two Propositions of Geometru — published posthumously

- 1662. Mr. Hobbes Considered in his Loyalty, Religion, Reputation, and Manners. By way of Letter to Dr. Wallis — English autobiography

- 1666. De Principis & Ratiocinatione Geometrarum

- 1666. A Dialogue between a Philosopher and a Student of the Common Laws of England (publ. 1681)

- 1668. Leviathan — Latin translation

- 1668. An answer to a book published by Dr. Bramhall, late bishop of Derry; called the Catching of the leviathan. Together with an historical narration concerning heresie, and the punishment thereof (publ. 1682)

- 1671. Three Papers Presented to the Royal Society Against Dr. Wallis. Together with Considerations on Dr. Wallis his Answer to them

- 1671. Rosetum Geometricum, sive Propositiones Aliquot Frustra antehac tentatae. Cum Censura brevi Doctrinae Wallisianae de Motu

- 1672. Lux Mathematica. Excussa Collisionibus Johannis Wallisii

- 1673. English translation of Homer's Iliad and Odyssey

- 1674. Principia et Problemata Aliquot Geometrica Antè Desperata, Nunc breviter Explicata & Demonstrata

- 1678. Decameron Physiologicum: Or, Ten Dialogues of Natural Philosophy

- 1679. Thomae Hobbessii Malmesburiensis Vita. Authore seipso — Latin autobiography

- Translated into English in 1680

Posthumous works

- 1680. An Historical Narration concerning Heresie, And the Punishment thereof

- 1681. Behemoth, or The Long Parliament

- Written in 1668, it was unpublished at the request of the King

- First pirated edition: 1679

- 1682. Seven Philosophical Problems (English translation of Problematica Physica, 1662)

- 1682. A Garden of Geometrical Roses (English translation of Rosetum Geometricum, 1671)

- 1682. Some Principles and Problems in Geometry (English translation of Principia et Problemata, 1674)

- 1688. Historia Ecclesiastica Carmine Elegiaco Concinnata

Complete editions

Molworth editions

Editions compiled by William Molesworth.

| Volume | Featured works |

|---|---|

| Volume I | Elementorum Philosophiae I: De Corpore |

| Volume II | Elementorum Philosophiae II and III: De Homine and De Cive |

| Volume III | Latin version of Leviathan. |

| Volume IV | Various concerning mathematics, geometry and physics |

| Volume V | Various short works. |

| Volume | Featured Works |

|---|---|

| Volume 1 | De Corpore translated from Latin to English. |

| Volume 2 | De Cive. |

| Volume 3 | The Leviathan |

| Volume 4 |

|

| Volume 5 | The Questions concerning Liberty, Necessity and Chance, clearly stated and debated between Dr Bramhall Bishop of Derry and Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury. |

| Volume 6. |

|

| Volume 7. |

|

| Volume 8 | The Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, translated into English by Hobbes. |

| Volume 9 | |

| Volume 10 | The Iliad and The Odyssey, translated by Hobbes into English |

| Volume 11 | Index |

Posthumous works not included in the Molesworth editions

| Work | Published year | Editor | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic (1st complete ed.) | London: 1889 | Ferdinand Tönnies, with a preface and critical notes | |

| "Short Tract on First Principles." Pp. 193–210 in Elements, Appendix I. | This work is now attributed to Robert Payne. | ||

| Tractatus opticus II (1st partial ed.) pp. 211–26 in Elements, Appendix II. | 1639, British Library, Harley MS 6796, ff. 193–266 | ||

| Tractatus opticus II (1st complete ed.) Pp. 147–228 in Rivista critica di storia della filosofia 18 | 1963 | Franco Alessio | Omits the diagrams |

| Critique du 'De mundo' de Thomas White | Paris: 1973 | Jean Jacquot and Harold Whitmore Jones | Includes three appendixes:

|

| Of the Life and History of Thucydides Pp. 10–27 in Hobbes's Thucydides | New Brunswick: 1975 | Richard Schlatter | |

| Three Discourses: A Critical Modern Edition of Newly Identified Work of the Young Hobbes (TD) Pp. 10–27 in Hobbes's Thucydides | Chicago: 1975 | Noel B. Reynolds and Arlene Saxonhouse | Includes:

|

| Thomas Hobbes' A Minute or First Draught of the Optiques (critical ed.) | University of Wisconsin-Madison: 1983 | Elaine C. Stroud | British Library, Harley MS 3360 Ph.D. dissertation |

| Of Passions Pp. 729–38 in Rivista di storia della filosofia 43 | 1988 | Anna Minerbi Belgrado | Edition of the unpublished manuscript Harley 6093 |

| The Correspondence of Thomas Hobbes (I: 1622–1659; II: 1660–1679) Clarendon Edition, vol. 6–7 | Oxford: 1994 | Noel Malcolm |

Translations in modern English

- De Corpore, Part I. Computatio Sive Logica. Edited with an Introductory Essay by L C. Hungerland and G. R. Vick. Translation and Commentary by A. Martinich. New York: Abaris Books, 1981.

- Thomas White's De mundo Examined, translation by H. W. Jones, Bradford: Bradford University Press, 1976 (the appendixes of the Latin edition (1973) are not enclosed).

New critical editions of Hobbes' works

- Clarendon Edition of the Works of Thomas Hobbes, Oxford: Clarendon Press (10 volumes published of 27 planned).

- Traduction des œuvres latines de Hobbes, under the direction of Yves Charles Zarka, Paris: Vrin (5 volumes published of 17 planned).

See also

- Natural and legal rights § Thomas Hobbes

- Natural law § Hobbes

- Hobbesian trap

- Conatus § In Hobbes

- Joseph Butler

- Hobbes's moral and political philosophy

- Leviathan and the Air-Pump

References

Citations

- ^ a b Thomas Hobbes (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

- ^ Kenneth Clatterbaugh, The Causation Debate in Modern Philosophy, 1637–1739, Routledge, 2014, p. 69.

- ^ a b Sorell, Tom (1996). Sorell, Tom (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Hobbes. Cambridge University Press. p. 155. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521410193. ISBN 9780521422444.

- ^ Hobbes, Thomas (1682). Tracts of Mr. Thomas Hobbs of Malmsbury: Containing I. Behemoth, the history of the causes of the civil wars of England, from 1640. to 1660. printed from the author's own copy: never printed (but with a thousand faults) before. II. An answer to Arch-bishop Bramhall's book, called the Catching of the Leviathan: never printed before. III. An historical narration of heresie, and the punishment thereof: corrected by the true copy. IV. Philosophical problems, dedicated to the King in 1662. but never printed before. W. Crooke. p. 339.

- ^ Williams, Garrath. "Thomas Hobbes: Moral and Political Philosophy." Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ Sheldon, Dr. Garrett Ward (2003). The History of Political Theory: Ancient Greece to Modern America. Peter Lang. p. 253. ISBN 9780820423005.

- ^ Lloyd, Sharon A., and Susanne Sreedhar. 2018. "Hobbes's Moral and Political Philosophy." Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ "Thomas Hobbes Biography." Encyclopedia of World Biography. Advameg, Inc. 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ Hobbes, Thomas (1679). "Opera Latina". In Molesworth, William(ed.). Vita carmine expressa. I. London. p. 86.

- ^ Jacobson, Norman; Rogow, Arnold A. (1986). "Thomas Hobbes: Radical in the Service of Reaction". Political Psychology. W.W. Norton. 8 (3): 469. doi:10.2307/3791051. ISBN 9780393022889. ISSN 0162-895X. JSTOR 3791051. LCCN 79644318. OCLC 44544062.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sommerville, J.P. (1992). Thomas Hobbes: Political Ideas in Historical Context. MacMillan. pp. 256–324. ISBN 9780333495995.

- ^ a b c d Robertson 1911, p. 545.

- ^ "Philosophy at Hertford College". Oxford: Hertford College. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ^ Helden, Al Van (1995). "Hobbes, Thomas". The Galileo Project. Rice University. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ^ King, Preston T. (1993). Thomas Hobbes: Politics and law. Routledge. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-41508083-5.

- ^ Malcolm, Noel (2004). "Hobbes, Thomas (1588–1679), philosopher". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13400. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ O'Connor, J. J.; Robertson, E. F. (November 2002). "Thomas Hobbes". School of Mathematics and Statistics. Scotland: University of St Andrews. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ^ Hobbes, Thomas (1995). Reynolds, Noel B.; Saxonhouse, Arlene W. (eds.). Three Discourses: A Critical Modern Edition of Newly Identified Work of the Young Hobbes. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226345451.

- ^ a b c d Robertson 1911, p. 546.

- ^ Bickley, F. (1914). The Cavendish family. Рипол Классик. p. 44. ISBN 9785874871451.

- ^ a b c d e f g Robertson 1911, p. 547.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Robertson 1911, p. 548.

- ^ Vardanyan, Vilen (2011). Panorama of Psychology. AuthorHouse. p. 72. ISBN 9781456700324..

- ^ Aubrey, John (1898) [1669–1696]. Clark, A. (ed.). Brief Lives: Chiefly of Contemporaries. II. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 277.

- ^ Robertson 1911, p. 550.

- ^ "House of Commons Journal Volume 8". British History Online. Retrieved 14 January 2005.

- ^ a b c d Robertson 1911, p. 551.

- ^ Grounds, Eric; Tidy, Bill; Stilgoe, Richard (25 November 2014). The Bedside Book of Final Words. Amberley Publishing Limited. p. 20. ISBN 9781445644646.

- ^ Norman Davies, Europe: A history p. 687

- ^ Coulter, Michael L.; Myers, Richard S.; Varacalli, Joseph A. (5 April 2012). Encyclopedia of Catholic Social Thought, Social Science, and Social Policy: Supplement. Scarecrow Press. p. 140. ISBN 9780810882751.

- ^ Gaskin. "Introduction". Human Nature and De Corpore Politico. Oxford University Press. p. xxx.

- ^ "Chapter XIII.: Of the Natural Condition of Mankind As Concerning Their Felicity, and Misery.". Leviathan.

- ^ Part I, Chapter XIV. Of the First and Second Naturall Lawes, and of Contracts. (Not All Rights are Alienable), Leviathan: "And therefore there be some Rights, which no man can be understood by any words, or other signes, to have abandoned, or tranferred. As first a man cannot lay down the right of resisting them, that assault him by force, to take away his life; because he cannot be understood to ayme thereby, at any Good to himselfe. The same may be sayd of Wounds, and Chayns, and Imprisonment".

- ^ Gaskin. "Of the Rights of Sovereigns by Institution". Leviathan. Oxford University Press. p. 117.

- ^ "1000 Makers of the Millennium", p. 42. Dorling Kindersley, 1999

- ^ Vélez, F., La palabra y la espada (2014)

- ^ Ameriks, Karl; Clarke, Desmond M. (2007). Chappell, Vere (ed.). Hobbes and Bramhall on Liberty and Necessity (PDF). Cambridge University Press. p. 31. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511495830. ISBN 9780511495830. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ Robertson 1911, p. 549.

- ^ p. 282 of Molesworth's edition.

- ^ Martinich, A. P. (1995). A Hobbes Dictionary. Cambridge: Blackwell. p. 35.

- ^ Martinich, A. P. (1995). A Hobbes Dictionary. Cambridge: Blackwell. p. 31.

- ^ Human Nature I.XI.5.

- ^ Leviathan III.xxxii.2. "...we are not to renounce our Senses, and Experience; nor (that which is undoubted Word of God) our naturall Reason".

- ^ Reynolds, Noel B. and Arlene W. Saxonhouse, eds. 1995. Three Discourses: A Critical Modern Edition of Newly Identified Work of the Young Hobbes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226345451.

- ^ Hobbes, Thomas. 1630. A Short Tract on First Principles, British Museum, Harleian MS 6796, ff. 297–308.

- ^ Bernhardt, Jean. 1988. Court traité des premiers principes. Paris: PUF. (Critical edition with commentary and French translation).

- ^ Richard Tuck, Timothy Raylor, and Noel Malcolm vote for Robert Payne. Karl Schuhmann, Cees Leijenhorst, and Frank Horstmann vote for Thomas Hobbes. See the excellent and extended essays Robert Payne, the Hobbes Manuscripts, and the 'Short Tract' (Noel Malcolm, in: Aspects of Hobbes. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2002. pp. 80–145) and Der vermittelnde Dritte (Frank Horstmann, in: Nachträge zu Betrachtungen über Hobbes' Optik. Mackensen, Berlin 2006, ISBN 978-3-926535-51-1. pp. 303–428.)

- ^ Harwood, John T., ed. 1986. The Rhetorics of Thomas Hobbes and Bernard Lamy. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. (Provides a new edition of the work).

- ^ Schuhmann, Karl (1998). "Skinner's Hobbes". British Journal for the History of Philosophy. 6 (1): 115. doi:10.1080/09608789808570984. p. 118.

- ^ Skinner, Quentin. 2012. Hobbes and Civil Science, (Visions of Politics 3). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511613784. (Skinner affirms Schuhmann's view: p. 4, fn. 27.)

- ^ Evrigenis, Ioannis D. 2016. Images of Anarchy: The Rhetoric and Science in Hobbes's State of Nature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 48, n. 13. (Provides a summary of this confusing episode, as well as most relevant literature.)

- ^ Hobbes, John. 1639. Tractatus opticus II. vis British Library, Harley MS6796, ff. 193–266.

- ^ First complete edition: 1963. For this dating, see the convincing arguments given by: Horstmann, Frank. 2006. Nachträge zu Betrachtungen über Hobbes' Optik. Berlin: Mackensen. ISBN 978-3-926535-51-1. pp. 19–94.

- ^ A critical analysis of Thomas White (1593–1676) De mundo dialogi tres, Parisii, 1642.

- ^ Hobbes, Thomas. 1646. A Minute or First Draught of the Optiques via Harley MS 3360.

- ^ Modern scholars are divided as to whether or not this translation was done by Hobbes. For a pro-Hobbes account see H. Warrender's introduction to De Cive: The English Edition in The Clarendon Edition of the Works of Thomas Hobbes (Oxford, 1984). For the contra-Hobbes account see Noel Malcolm, "Charles Cotton, Translator of Hobbes's De Cive" in Aspects of Hobbes (Oxford, 2002)

- ^ critical edition: Court traité des premiers principes, text, French translation and commentary by Jean Bernhardt, Paris: PUF, 1988

- ^ Timothy Raylor, "Hobbes, Payne, and A Short Tract on First Principles", The Historical Journal, 44, 2001, pp. 29–58.

Sources

Attribution:

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Robertson, George Croom; Anonymous texts (1911). "Hobbes, Thomas". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 545–552.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Robertson, George Croom; Anonymous texts (1911). "Hobbes, Thomas". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 545–552.

Further reading

General resources

- MacDonald, Hugh & Hargreaves, Mary. Thomas Hobbes, a Bibliography, London: The Bibliographical Society, 1952.

- Hinnant, Charles H. (1980). Thomas Hobbes: A Reference Guide, Boston: G. K. Hall & Co.

- Garcia, Alfred (1986). Thomas Hobbes: bibliographie internationale de 1620 à 1986, Caen: Centre de Philosophie politique et juridique Université de Caen.

Critical studies

- Brandt, Frithiof (1928). Thomas Hobbes' Mechanical Conception of Nature, Copenhagen: Levin & Munksgaard.

- Jesseph, Douglas M. (1999). Squaring the Circle. The War Between Hobbes and Wallis, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Leijenhorst, Cees (2002). The Mechanisation of Aristotelianism. The Late Aristotelian Setting of Thomas Hobbes' Natural Philosophy, Leiden: Brill.

- Lemetti, Juhana (2011). Historical Dictionary of Hobbes's Philosophy, Lanham: Scarecrow Press.

- Macpherson, C. B. (1962). The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism: Hobbes to Locke, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Malcolm, Noel (2002). Aspects of Hobbes, New York: Oxford University Press.

- MacKay-Pritchard, Noah (2019). "Origins of the State of Nature", London

- Malcolm, Noel (2007). Reason of State, Propaganda, and the Thirty Years' War: An Unknown Translation by Thomas Hobbes, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Manent, Pierre (1996). An Intellectual History of Liberalism, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Martinich, A. P. (2003) "Thomas Hobbes" in The Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 281: British Rhetoricians and Logicians, 1500–1660, Second Series, Detroit: Gale, pp. 130–44.

- Martinich, A. P. (1995). A Hobbes Dictionary, Cambridge: Blackwell.

- Martinich, A. P. (1997). Thomas Hobbes, New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Martinich, A. P. (1992). The Two Gods of Leviathan: Thomas Hobbes on Religion and Politics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Martinich, A. P. (1999). Hobbes: A Biography, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Narveson, Jan; Trenchard, David (2008). "Hobbes, Thomas (1588–1676)". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). Hobbes, Thomas (1588–1679). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; Cato Institute. pp. 226–27. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n137. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- Oakeshott, Michael (1975). Hobbes on Civil Association, Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Parkin, Jon, (2007), Taming the Leviathan: The Reception of the Political and Religious Ideas of Thomas Hobbes in England 1640–1700, [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press]

- Pettit, Philip (2008). Made with Words. Hobbes on Language, Mind, and Politics, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Robinson, Dave and Groves, Judy (2003). Introducing Political Philosophy, Icon Books. ISBN 1-84046-450-X.

- Ross, George MacDonald (2009). Starting with Hobbes, London: Continuum.

- Shapin, Steven and Shaffer, Simon (1995). Leviathan and the Air-Pump. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Skinner, Quentin (1996). Reason and Rhetoric in the Philosophy of Hobbes, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Skinner, Quentin (2002). Visions of Politics. Vol. III: Hobbes and Civil Science, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Stomp, Gabriella (ed.) (2008). Thomas Hobbes, Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Strauss, Leo (1936). The Political Philosophy of Hobbes; Its Basis and Its Genesis, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Strauss, Leo (1959). "On the Basis of Hobbes's Political Philosophy" in What Is Political Philosophy?, Glencoe, IL: Free Press, chap. 7.

- Tönnies, Ferdinand (1925). Hobbes. Leben und Lehre, Stuttgart: Frommann, 3rd ed.

- Tuck, Richard (1993). Philosophy and Government, 1572–1651, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Vélez, Fabio (2014). La palabra y la espada: a vueltas con Hobbes, Madrid: Maia.

- Vieira, Monica Brito (2009). The Elements of Representation in Hobbes, Leiden: Brill Publishers.

- Zagorin, Perez (2009). Hobbes and the Law of Nature, Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.