閱讀赫西俄德 Hesiod在诗海的作品!!! | |||

創作及評價

在荷馬之後,古希臘思想史上還有一位偉大的現實主義與浪漫主義詩人赫西俄德。據認為,流傳下來的《工作與時日》和《神譜》都是他的作品。近代學者認為,赫西俄德的作品反映的是公元前8世紀的希臘社會生活。這應當看做是對他的《工作與時日》的評價。《神譜》則繼承了荷馬的風格與倫理價值觀。因此,這是兩個從思想內容到風格都極不相同的作品,所反映的道德觀念也是兩種形態。《工作與時日》是現實主義的並以對人們進行道德勸教為中心,《神譜》則是浪漫主義的並不進行人間道德風化的考慮。

赫西俄德繼承了荷馬的風格,以浪漫主義手法譜寫的《神譜》,寫了一個希臘諸神的世代譜係。在作者的筆下,奧林匹斯聖山上的衆神們享有着無限榮光,赫西俄德把人間價值的光環都賦予了衆神,他們是永遠快樂而且是永生不死的。而最值得我們註意的是, 不朽的衆神們並非受到人間的道德規範的製約。從我們今天的性關係的道德觀點來看,赫西俄德的希臘諸神的譜係學,就是一個亂倫的譜係學(實際上它在某種意義上反映了人類早期的兩性關係)。大地之神該亞首先生了天神烏蘭諾斯。然而,大地該亞(地母)與其子天神烏蘭諾斯交合,生下衆神,其中一個最小但最可怕的就是狡猾多計的剋洛諾斯。其次,這個譜係也是一個由於性關係的紊亂而發生代際衝突的譜係。在大地之神該亞眼裏,天神是一個到處與異性發生關係的強大的神,並因此引起了地母的強烈嫉妒,所以她讓他們的兒子剋洛諾斯去懲罰無恥的父親。這就是當他父親渴求愛情,擁抱大地該亞時,他割下父親的生殖器並將它扔在他的後面。這個故事對於弗洛依德有着直接的啓迪。在他看來,人類的早期有着一種父輩與子輩之間為了異性而進行的戰爭,即父親對異性的占有。它導致的就是弒父情結。同時,《神譜》告訴我們,這是一個力的統治的世界。在宙斯出生之前,天神的世界由剋洛諾斯統治着。然而,他從父親天神和母親地母那裏得知,儘管他很強大,但註定要為自己的一個兒子所推翻。於是,每當妻子生下一個孩子,剋洛諾斯都把他吞到自己的肚子裏。宙斯出生時,其母隱瞞其父纔得以死裏逃生。不久這個兒子就憑強力打敗了他的父親,剝奪了他的一切尊榮,取而代之成為衆神之王。

在赫西俄德的衆神譜係裏,不僅在神那裏找不到對人類性道德的遵守,而且人類的惡也變成了神的本性,或者說,人類的惡化身成了神。這類神有:欺騙女神、不饒人的或惡意的不和女神、爭鬥女神、謀殺女神、謊言女神、違法女神等等。 她們也是不死的而且也是光輝的奧林匹斯衆神之一!在赫西俄德看來,神本身就是罪惡之源。赫西俄德也把人類的罪惡看成是來自於衆神(如潘多拉的盒子),正如他把人類的光明如人間得到的火種看成是來自於神一樣。不過,人類得到火種全在於一位神(普羅米修斯)欺瞞宙斯而偷給人類的!由此宙斯還給人類帶來了更多的不幸。重要的是,我們要看到,在赫西俄德的筆下描寫的衆神們的生活,找不到人間道德的影子。尼采曾深刻指出:“誰要是心懷另一種宗教走嚮奧林匹斯山,竟想在它那裏尋找道德的高尚,聖潔,無肉體的空靈,悲天憫人的目光,他就必定悵然失望,立刻掉首而去。這裏沒有任何東西使人想起苦行、修身和義務;這裏衹有一種豐滿的乃至凱旋的生存嚮我們說話,在這個生存之中,一切存在物不論善惡都被尊崇為神。”在愛利亞學派的剋塞諾芬尼(約公元前5世紀人)流傳下來的《著作殘篇》中,他寫道:“荷馬和赫西俄德把人間認為是無恥醜行的一切都加在神靈身上:偷盜、姦淫、彼此欺詐。” 不過,這並不是荷馬和赫西俄德憑自我意願要這樣做,他們的描述反映的是那個時期的希臘人心目中的神。神的世界並非是一個道德法則所統治的世界,而是一個力量所統治的世界。我們所看到的,是衆神或作者對於力的崇拜。宙斯之所以能夠超過其父而成為衆神之王,就在於他的神力,不在於他的道德或公正。而且我們讀到,宙斯總在和別的女神同床交歡。力量與原始本性的快樂同樣得到了詩人們的歌頌。實際上,這樣一個神譜,反映的是希臘祖先原始野蠻的風俗,反映的是它的徵服與掠奪的歷史。

在赫西俄德的《工作與時日》裏,與《神譜》相反,充滿了道德的說教或訓誡。在他看來,道德規則或道德秩序是人類生活的法則,雖然它們不是衆神生活的法則。並且,雖然衆神自己的生活不守法則,但是,他們卻在上天管理着人類法則的執行。宙斯在這裏成了公道、正義和最高法律的化身。他正直、無私、全智,對一切違反法律的惡人都給予應有的懲罰。“無論誰強暴行兇,剋洛諾斯之子、千裏眼宙斯都將予以懲罰。”在《神譜》中,神的世界裏力量是决定統治的决定性因素,而在人類社會如果把力量看成是正義的依據,如果認為力量就是正義,虔誠不是美德,那麽,人類將陷入深重的悲哀,面對罪惡而無處求助。《工作與時日》說:“你要傾聽正義,不要希求暴力,因為暴力無益於貧窮者,甚至傢財萬貫的富人也不容易承受暴力,一旦碰上厄運,就永遠翻不了身。反之,追求正義是明智之舉,因為正義最終要戰勝強暴。” 赫西俄德認為,正義是城市繁榮、人民富庶以及社會和平的根本保障。但何為正義?在《工作與時日》裏,沒有可以解釋的詞語。不過,《工作與時日》將正義與暴力、欺騙、作偽證或謊言對立起來,實際上就是把正義看成是公正或正直。值得註意的是,把正義與強暴對立起來,實際上強調了正義就是一種理性,它不是一種自然力量,是一種理性力量。在《工作與時日》看來,人們應當依據正義的法則來解决人們之間的爭端,而不是依據暴力。在赫西俄德看來,人與其他動物區別的根本所在就是人類知道什麽是正義,並依據正義來行事,而其他動物如魚、獸以及鳥類,在它們之間沒有正義,所以互相吞食。是宙斯把正義這個最好的禮物給了人類。“任何人衹要知道正義並且講正義,無所不見的宙斯就會給他幸福。”我們看到,在荷馬史詩那裏,也強調正義,但同時強調力量,尤其是人類的或神的自然力量或有機體的力量。在荷馬那裏, 正義與力量是一對潛在的矛盾。在赫西俄德這裏,則把神的世界完全歸於力量的統治,而人類社會則歸於正義的統治。正義作為一種法則,它不訴求人的力量,而所訴求的是人的理性。

其次,赫西俄德的《工作與時日》的一個顯著特徵就是對世俗生活道德的極端重視。在赫西俄德看來,勞動是人的幸福之本。人類衹有通過勞動才能增加羊群和財富,善德和聲譽與財富為伍。“如果你把不正的心靈從別人的財富上移到你的工作上,留心從事如我所囑咐你的生計, 不論你的運氣如何,勞動對你都是上策。”憑自己的勞動致富,不拿不義之財,尤其不以暴力掠奪他人財富,是《工作與時日》中的一項基本道德勸教。這裏把掠奪財富看成是與傷害懇求者、冷待客人、亂倫、虐待孤兒、斥駡年老少歡的父親等惡行一樣的罪惡。在這個意義上,《工作與時日》所註重的就是日常和平生活的倫理。這與荷馬史詩中的英雄以掠奪、徵戰為榮的倫理觀完全不同。從這種倫理觀的變化我們可以看到,希臘已經從一種徵戰掠奪的遊牧民族過渡到一種以農業為主的過鄉村生活的民族。

不義之財遭受到道德的譴責,那麽幸福就在於自己的勤奮勞動。在赫西俄德這裏,生活所必需的不是戰車和馬匹,而是住所、女人和耕牛。在《工作與時日》中,生産勞動與人們的正義、誠實等德性具有對人們的生活幸福而言的同等重要性。在赫西俄德看來,一個人要過上體面的幸福生活,一定的生活資料是不可或缺的,而生活資料取得的唯一正當途徑就在於勤勞。與荷馬史詩的英雄倫理觀不同,赫西俄德的《工作與時日》提出了一種世俗生活的幸福倫理觀。換言之,他提出了在一種田園牧歌的和平環境下,什麽樣的生活纔是真正幸福生活的問題。因此,在西方倫理思想史上,是赫西俄德第一個思考了人類的和平生活秩序以及和平生活中的幸福問題。我認為,赫西俄德提出的最基本的生活倫理以及誠實勞動的幸福觀念,回答了一般性人類社會生活秩序的倫理建構問題,從而具有普遍意義。不得以暴力掠奪他人財富,是《工作與時日》中的一項基本道德勸教。赫西俄德以勸告的形式提出不得掠奪他人財富、不得傷害懇求者、冷待客人、亂倫、虐待孤兒、斥駡年老少歡的父親等,實際上提出了最低限度的生活秩序得以建構的倫理要素。能做到這些,也就是公正,也就有了人類生活的和平與秩序。當然,赫西俄德不僅從消極的意義上提出了人們不應當做什麽,也從積極的意義上嚮人們提出了應當做什麽。他提出人們應當勤勉、公正、善待友人,待人以誠,以及“鄰居對你有多好,你也應該對他也有多好”。既有最低限度的道德要求,又有應當切實努力的方向。他所提出的這樣兩個方面的具體內容,都是個人生活以及社會生活的幸福與安寧所必需的。

赫西俄德的兩部著作體現了這樣的兩重倫理觀,一個是崇尚力的神的世界,另一個則是應當遵守正義、公正的道德規則的世界。將神的世界看成是超脫於人類的道德法則而由力所統治的世界,而衹將道德法則的遵守限定在人類社會。他認為,在人間社會, 如果像神的世界那樣崇尚強力並由力量來統治而不講公正,必將陷入災難而難於自拔。這個真理至今沒有過時,而且永遠不會過時。我們這個人類社會,自從上個世紀的二次世界大戰後,纔有了一種共識:暴力徵服、殖民侵略與擴張的時代應當結束了。但這並不意味着我們這個世界就處在公正而有序的世界秩序之中,強暴的力量時時都在侵犯公正。

Hesiod's writings serve as a major source on Greek mythology, farming techniques, archaic Greek astronomy and ancient time-keeping.

Life

J. A. Symonds writes that "'Hesiod is also the immediate parent of gnomic verse, and the ancestor of those deep thinkers who speculated in the Attic Age upon the mysteries of human life".

Some scholars have doubted whether Hesiod alone conceived and wrote the poems attributed to him. For example, Symonds writes that "the first ten verses of the Works and Days are spurious - borrowed probably from some Orphic hymn to Zeus and recognised as not the work of Hesiod by critics as ancient as Pausanias".

As with Homer, legendary traditions have accumulated around Hesiod. Unlike Homer's case, however, some biographical details have survived: a few details of Hesiod's life come from three references in Works and Days; some further inferences derive from his Theogony. His father came from Cyme in Aeolis, which lay between Ionia and the Troad in Northwestern Anatolia, but crossed the sea to settle at a hamlet near Thespiae in Boeotia named Ascra, "a cursed place, cruel in winter, hard in summer, never pleasant" (Works, l. 640). Hesiod's patrimony there, a small piece of ground at the foot of Mount Helicon, occasioned a pair of lawsuits with his brother Perses, who won both under the same judges.

Some scholars have seen Perses as a literary creation, a foil for the moralizing that Hesiod directed to him in Works and Days, but in the introduction to his translation of Hesiod's works, Hugh G. Evelyn-White provides several arguments against this theory. Gregory Nagy, on the other hand, sees both Persēs ("the destroyer": πέρθω / perthō) and Hēsiodos ("he who emits the voice": ἵημι / hiēmi + αὐδή / audē) as fictitious names for poetical personae.

The Muses traditionally lived on Helicon, and, according to the account in Theogony (ll. 22-35), gave Hesiod the gift of poetic inspiration one day while he tended sheep (compare the legend of Cædmon). Hesiod later mentions a poetry contest at Chalcis in Euboea where the sons of one Amiphidamas awarded him a tripod (ll.654-662). Plutarch first cited this passage as an interpolation into Hesiod's original work, based on his identification of Amiphidamas with the hero of the Lelantine War between Chalcis and Eretria, which occurred around 705 BC. Plutarch assumed this date much too late for a contemporary of Homer, but most Homeric scholars would now accept it. The account of this contest, followed by an allusion to the Trojan War, inspired the later tales of a competition between Hesiod and Homer.

Two different -- yet early -- traditions record the site of Hesiod's grave. One, as early as Thucydides, reported in Plutarch, the Suda and John Tzetzes, states that the Delphic oracle warned Hesiod that he would die in Nemea, and so he fled to Locris, where he was killed at the local temple to Nemean Zeus, and buried there. This tradition follows a familiar ironic convention: the oracle that predicts accurately after all.

The other tradition, first mentioned in an epigram of Chersios of Orchomenus written in the 7th century BC (within a century or so of Hesiod's death) claims that Hesiod lies buried at Orchomenus, a town in Boeotia. According to Aristotle's Constitution of Orchomenus, when the Thespians ravaged Ascra, the villagers sought refuge at Orchomenus, where, following the advice of an oracle, they collected the ashes of Hesiod and placed them in a place of honour in their agora, beside the tomb of Minyas, their eponymous founder, and in the end came to regard Hesiod too as their "hearth-founder" (οἰκιστής / oikistēs).

Later writers attempted to harmonize these two accounts.

The legends that accumulated about Hesiod are recorded in several sources: the story "The poetic contest (Ἀγών / Agōn) of Homer and Hesiod"; a vita of Hesiod by the Byzantine grammarian John Tzetzes; the entry for Hesiod in the Suda; two passages and some scattered remarks in Pausanias (IX, 31.3–6 and 38.3–4); a passage in Plutarch Moralia (162b).

Works

Of the many works attributed to Hesiod, three survive complete and many more in fragmentary state. Our witnesses include Alexandrian papyri, some dating from as early as the 1st century BC, and manuscripts written from the eleventh century forward. Demetrius Chalcondyles issued the first printed edition (editio princeps) of Works and Days, possibly at Milan, probably in 1493. In 1495 Aldus Manutius published the complete works at Venice.

Hesiod's works, especially Works and Days, are from the view of the small independent farmer, while Homer's view is from nobility or the rich. Even with these differences, they share some of the same beliefs as far as work ethic, justice, and consideration of material items.

Works and Days

Main article: Works and Days

Hesiod wrote a poem of some 800 verses, the Works and Days, which revolves around two general truths: labour is the universal lot of Man, but he who is willing to work will get by. Scholars have interpreted this work against a background of agrarian crisis in mainland Greece, which inspired a wave of documented colonisations in search of new land.

This work lays out the five Ages of Man, as well as containing advice and wisdom, prescribing a life of honest labour and attacking idleness and unjust judges (like those who decided in favour of Perses) as well as the practice of usury. It describes immortals who roam the earth watching over justice and injustice. The poem regards labor as the source of all good, in that both gods and men hate the idle, who resemble drones in a hive.

Theogony

Main article: Theogony

Tradition also attributes the Theogony, a poem which uses the same epic verse-form as the Works and Days, to Hesiod. Despite the different subject-matter most scholars, with some notable exceptions like Evelyn-White, believe both works were written by the same man. As M.L. West writes, "Both bear the marks of a distinct personality: a surly, conservative countryman, given to reflection, no lover of women or life, who felt the gods' presence heavy about him."

The Theogony concerns the origins of the world (cosmogony) and of the gods (theogony), beginning with Gaia, Nyx and Eros, and shows a special interest in genealogy. Embedded in Greek myth there remain fragments of quite variant tales, hinting at the rich variety of myth that once existed, city by city; but Hesiod's retelling of the old stories became, according to the fifth century historian Herodotus, the accepted version that linked all Hellenes.

Other writings

A short poem traditionally attributed to Hesiod is The Shield of Heracles (Ἀσπὶς Ἡρακλέους / Aspis Hêrakleous). This survives complete; the other works discussed in this section survive only in quotations or papyri copies which are often damaged.

Classical authors also attributed to Hesiod a lengthy genealogical poem known as Catalogue of Women or Eoiae (because sections began with the Greek words e oie 'Or like the one who...'). It was a mythological catalogue of the mortal women who had mated with gods, and of the offspring and descendants of these unions.

Several additional poems were sometimes ascribed to Hesiod:

Aegimius

Astrice

Chironis Hypothecae

Idaei Dactyli

Wedding of Ceyx

Great Works (presumably an expanded Works and Days)

Great Eoiae (presumably an expanded Catalogue of Women)

Melampodia

Ornithomantia

Scholars generally classify all these as later examples of the poetic tradition to which Hesiod belonged, not as the work of Hesiod himself. The Shield, in particular, appears to be an expansion of one of the genealogical poems, taking its cue from Homer's description of the Shield of Achilles.

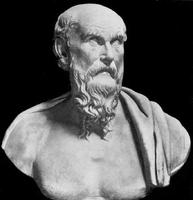

The "portrait" bust

The Roman bronze bust of the late first century BC found at Herculaneum, the so-called Pseudo-Seneca was first reidentified as a fictitious portrait meant for Hesiod by Gisela Richter, though it had been recognized that the bust was not in fact Seneca since 1813, when an inscribed herm portrait with quite different features was discovered. Most scholars now follow her identification.

Notes

^ Erika Simon (1975). Pergamon und Hesiod (in German). Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern. OCLC 2326703.

^ M.L. West, "Hesiod", in Oxford Classical Dictionary, second edition (Oxford: University Press, 1970), p.510.

^ J. A. Symonds, Sbreasın strabnssk lkjsdaflj nsdurps sdflfsj toı urnststlhg aa şgg fgafn asdeut sgsgmg fmgfmgfmgktş.çföböbatudies of the Greek Poets, p. 166

^ J. A. Symonds, p. 167

^ Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Hesiod, The Homeric Hymns and Homerica (Cambridge: Harvard Press, 1964) Volume 57 of the Loeb Classical Library, pp. xivf.

^ Gregry Nagy, Greek Mythology and Poetics (Cornell 1990), pp. 36-82.

^ Translated in Evelyn-White, Hesiod, pp. 565-597.

^ Hesiod, Works and Days, line 250: "Verily upon the earth are thrice ten thousand immortals of the host of Zeus, guardians of mortal man. They watch both justice and injustice, robed in mist, roaming abroad upon the earth". (Compare J. A. Symonds, p. 179)

^ Works and Days, line 300: "Both gods and men are angry with a man who lives idle, for in nature he is like the stingless drones who waste the labor of the bees, eating without working."

^ West, "Hesiod", p. 521.

References

Philip Wentworth Buckham, Theatre of the Greeks, 1827.

Robert Lamberton, Hesiod, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. ISBN 0300040687

Pietro Pucci, Hesiod and the Language of Poetry, Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977. ISBN 0801817870

Erwin Rohde, Psyche, 1925.

J. A. Symonds, Studies of the Greek Poets, 1873.

Thomas Taylor, A Dissertation on the Eleusinian and Bacchic Mysteries, 1791.