yuèdòumǐ xiē 'ěr · fú kē Michel Foucaultzài百家争鸣dezuòpǐn!!! | |||||||

mǐ xiē 'ěr · fú kē - shēng píng

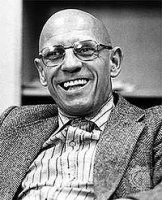

mǐ xiē 'ěr fú kē( MichelFoucault) 1926 nián 10 yuè 26 rì chū shēng yú fǎ guó wéi 'ài nà shěng shěng huì pǔ wǎ jié, zhè shì fǎ guó xī nán bù de yī gè níng jìng xiǎo chéng。 tā fù qīn shì gāi chéng yī wèi shòu rén zūn jìng de wài kē yī shēng, mǔ qīn yě shì wài kē yī shēng de nǚ 'ér。 fú kē zài pǔ wǎ jié wán chéng liǎo xiǎo xué hé zhōng xué jiào yù, 1945 nián, tā lí kāi jiā xiāng qián wǎng bā lí cān jiā fǎ guó gāo děng shī fàn xué xiào rù xué kǎo shì, bìng yú 1946 nián shùn lì jìn rù gāo shī xué xí zhé xué。 1951 nián tōng guò dà zhōng xué jiào shī zī gé huì kǎo hòu, tā zài tī yě 'ěr jī jīn huì zī zhù xià zuò liǎo 1 nián yán jiū gōng zuò, 1952 nián shòu pìn wéi lǐ 'ěr dà xué zhù jiào。

zǎo zài gāo shī qī jiān, fú kē jí biǎo xiàn chū duì xīn lǐ xué hé jīng shén bìng xué de jí dà xīng qù, qià hǎo tā fù mǔ de yī wèi shì jiāo yǎ kè lín nà wéi 'ěr dào( JacquelineVerdeaus) jiù shì xīn lǐ xué jiā, ér yǎ kè lín nà de zhàng fū qiáo zhì wéi 'ěr dào zé shì fǎ guó jīng shén fēn xī xué dà shī yǎ kè lā kāng de xué shēng。 yīn cǐ, zài wéi 'ěr dào fū fù de yǐng xiǎng xià, fú kē duì xīn lǐ xué hé jīng shén fēn xī xué jìn xíng liǎo xì tǒng shēn rù de xué xí, bìng yǔ yǎ kè lín nà yī dào fān yì liǎo ruì shì jīng shén bìng xué jiā bīn sī wàn gé 'ěr( LudwigBinswanger) de zhù zuò《 mèng yǔ cún zài》。 shū chéng zhī hòu, fú kē yìng yǎ kè lín nà zhī qǐng wéi fǎ wén běn zuò xù, bìng zài 1953 nián fù huó jié zhī qián cǎo jiù yī piān cháng dù chāo guò zhèng wén de xù yán。 zài zhè piān cháng wén zhōng, tā rì hòu guāng cǎi duó mùdì xiě zuò fēng gé yǐ jīng chū lù duān ní。 1954 nián, zhè běn hǎn jiàn de xù yán cháng guò zhèng wén de yì zuò yóu dé kè léi dé bù lǔ wò chū bǎn shè chū bǎn, shōu rù《 rén lèi xué zhù zuò hé yán jiū》 cóng shū。 tóng nián, fú kē fā biǎo liǎo zì jǐ de dì yī bù zhuān zhe《 jīng shén bìng yǔ rén gé》, shōu rù《 zhé xué rù mén》 cóng shū, yóu fǎ guó dà xué chū bǎn shè chū bǎn。 fú kē hòu lái duì zhè bù zhù zuò jiā yǐ fǒu dìng, rèn wéi tā bù chéng shú, yīn cǐ, 1962 nián zài bǎn shí zhè běn shū jīhū miàn mù quán fēi。

1955 nián 8 yuè, zài zhù míng shén huà xué jiā qiáo zhì dù méi zé 'ěr( GeorgesDumezil) de dà lì tuī jiàn xià, fú kē bèi ruì diǎn wū pǔ sà lā dà xué pìn wéi fǎ yǔ jiào shī。 zài ruì diǎn qī jiān, fú kē hái jiān rèn fǎ guó wài jiāo bù shè lì de“ fǎ guó zhī jiā” zhù rèn, yīn cǐ, jiào xué zhī wài, tā huā liǎo dà liàng shí jiān yòng yú zǔ zhì gè zhǒng wén huà jiāo liú huó dòng。 zài ruì diǎn de 3 nián shí jiān lǐ, fú kē kāi shǐ dòng shǒu zhuàn xiě bó shì lùn wén。 dé yì yú wū pǔ sà lā dà xué tú shū guǎn shōu cáng de yī dà pī 16 shì jì yǐ lái de yī xué shǐ dàng 'àn、 shū xìn hé gè zhǒng shàn běn tú shū, yě dé yì yú dù méi zé 'ěr de bù duàn dū cù hé bāng zhù, dāng fú kē lí kāi ruì diǎn shí《 fēng diān yǔ fēi lǐ zhì héng héng gǔ diǎn shí qī de fēng diān shǐ》 yǐ jīng jī běn wán chéng。

1958 nián, yóu yú gǎn dào jiào xué hé gōng zuò fù dān guò zhòng duì, fú kē tí chū cí zhí, bìng yú 6 yuè jiān huí dào bā lí。 liǎng gè yuè hòu, hái shì zài dù méi zé 'ěr de bāng zhù xià, tóng shí yě yīn wéi fú kē zài ruì diǎn qī jiān biǎo xiàn de chū sè zǔ zhì néng lì, tā bèi fǎ guó wài jiāo bù rèn mìng wéi shè zài huá shā dà xué nèi de fǎ guó wén huà zhōng xīn zhù rèn。 zhè nián 10 yuè, fú kē dào dá bō lán, bù guò tā bìng méi yòu zài nà 'ér dài tài jiǔ, yuán yīn dǎo yě fù yú xì jù xìng: tā zhōng liǎo bō lán qíng bào jī guān de měi nán jì。 fú kē cóng hěn zǎo shí hòu qǐ jiù shì tóng xìng liàn, duì cǐ tā dǎo bù jiā yǎn shì, jiù gè rén shēng huó 'ér yán, zhè wèi lǎo xiōng xiǎn rán gòu dé shàng“ fēng liú” de měi míng。 rán 'ér 50 nián dài zhèng shì dōng xī fāng lěng zhàn zhèng hān zhī shí, liǎng fāng dū zài wā kōng xīn sī de xiāng hù cì tàn。 qià qià zài 1959 nián, fǎ guó zhù bō lán dà shǐ guǎn wén huà cān zàn gàojià, dà shǐ běn yǐ yòu xīn tí bá fú kē, biàn yī miàn ràng tā dài xíng cān zàn zhí wù, yī miàn xíng wén bào qǐng zhèng shì rèn mìng。 suǒ yǐ bō lán qíng bào jī gòu chéng xū 'ér rù, fēng liú chéng xìng de nián qīng zhé xué jiā hé dāng zhòngjì。

lí kāi bō lán hòu, fú kē jì xù tā de hǎi wài zhī lǚ, zhè yī cì shì mùdì dì shì hàn bǎo, réng rán shì fǎ guó wén huà zhōng xīn zhù rèn。 1960 nián 2 yuè, fú kē zài dé guó zuì zhōng wán chéng liǎo tā de bó shì lùn wén。 zhè shì yī běn zài hòu dù hé shēn dù shàng dū tóng yàng lìng rén zā shé de dà shū: quán shū bāo kuò fù lù hé cān kǎo shū mù cháng dá 943 yè, kǎo chá liǎo zì 17 shì jì yǐ lái fēng diān hé jīng shén bìng guān niàn de liú biàn, xiáng jìn shū lǐ liǎo zài zào xíng yì shù、 wén xué hé zhé xué zhōng tǐ xiàn de fēng diān xíng xiàng xíng chéng、 zhuǎn biàn de guò chéng jí qí duì xiàn dài rén de yì yì。 àn zhào guàn lì, shēn qǐng guó jiā bó shì xué wèi de yīnggāi tí jiāo yī piān zhù lùn wén hé yī piān fù lùn wén, fú kē yīn cǐ jué dìng fān yì kāng dé de《 shí yòng rén lèi xué》 bìng yǐ yī piān dǎo yán zuò wéi fù lùn wén, suī rán zhè yī dǎo yán cóng lái méi yòu chū bǎn, dàn fú kē yán jiū zhě men fā xiàn, tā hòu lái chéng shú bìng fǎn yìng yú《 cí yǔ wù》、《 zhī shí kǎo gǔ xué》 zhōng de yī xiē zhòng yào gài niàn hé sī xiǎng, zài zhè piān lùn wén zhōng qí shí yǐ jīng xíng chéng。

yìng fú kē zhī qǐng, tā yǐ qián zài hēng lì sì shì zhōng xué de zhé xué lǎo shī, shí rèn bā lí gāo shī xiào cháng de ràng yī bō lì tè( JeanHyppolite) xīn rán tóng yì zuò fù lùn wén de“ yán jiū dǎo shī”, bìng tuī jiàn zhù míng kē xué shǐ jiā、 shí wéi bā lí dà xué zhé xué xì zhù rèn de qiáo zhì gāng kuí lāi mǔ( GeorgesConguilhem) dān rèn tā de zhù lùn wén dǎo shī。 hòu zhě duì《 fēng diān shǐ》 zàn yù yòu jiā, bìng wéi tā xiě liǎo rú xià píng yǔ“ rén men huì kàn dào zhè xiàng yán jiū de jià zhí suǒ zài, jiàn yú fú kē xiān shēng yī zhí guān zhù zì wén yì fù xīng shí qī zhì jīn jīng shén bìng zài zào xíng yì shù、 wén xué hé zhé xué zhōng fǎn yìng chū lái de xiàng xiàn dài rén tí gōng de duō zhǒng yòng tú; jiàn yú tā shí 'ér lǐ shùn、 shí 'ér yòu gǎo luàn fēn zá de 'ā lì 'ā dé ní xiàn tuán, tā de lùn wén róng fēn xī hé zōng hé yú yī lú, tā de yán jǐn, suī rán dú qǐ lái bù nà me qīng sōng, dàn què bù shī ruì zhì zhī zuò …… yīn cǐ, wǒ shēn xìn fú kē xiān shēng de yán jiū de zhòng yào xìng shì wú yōng zhì yí de。” 1961 nián 5 yuè 20 rì, fú kē shùn lì tōng guò dá biàn, huò dé wén xué bó shì xué wèi。 zhè piān lùn wén yě bèi píng wéi dāng nián zhé xué xué kē de zuì yōu xiù lùn wén, bìng bān fā gěi zuò zhě yī méi tóng pái。

hái zài fú kē tōng guò bó shì lùn wén dá biàn yǐ qián, kè lāi méng- fèi lǎng dà xué zhé xué xì xīn rèn xì zhù rèn wéi yě màn zài dú wán《 fēng diān shǐ》 shǒu gǎo hòu, jí zhì hán shàng yuǎn zài hàn bǎo de zuò zhě, xī wàng yán pìn tā wéi jiào shòu。 fú kē xīn rán jiē shòu, bìng yú 1960 nián 10 yuè jiù rèn dài lǐ jiào shòu, 1962 nián 5 yuè 1 rì, kè lāi méng - fèi lǎng dà xué zhèng shì shēng rèn fú kē wéi zhé xué xì zhèng jiào shòu。 zài zhěng gè 60 nián dài, fú kē de zhī míng dù suí zhe tā zhù zuò hé píng lùn wén zhāng de fā biǎo 'ér jí jù shàng shēng: 1963 nián《 léi méng lǔ sài 'ěr》 hé《 lín chuáng yī xué de dàn shēng》, 1964 nián《 ní cǎi、 fú luò yī dé、 mǎ kè sī》 yǐ jí 1966 nián yǐn qǐ jí dà fǎn xiǎng de《 cí yǔ wù》。

zhè bù zhù zuò lì tú gòu jiàn yī zhǒng“ rén wén kē xué kǎo gǔ xué”, tā“ zhǐ zài cè dìng zài xī fāng wén huà zhōng, rén de tàn suǒ cóng hé shí kāi shǐ, zuò wéi zhī shí duì xiàng de rén hé shí chū xiàn。” ] fú kē shǐ yòng“ zhī shí xíng” zhè yī xīn shù yǔ zhǐ chēng tè dìng shí qī zhī shí chǎn shēng、 yùn dòng yǐ jí biǎo dá de shēn céng kuàng jià。 tōng guò duì wén yì fù xīng yǐ lái zhī shí xíng zhuǎn biàn liú dòng de kǎo chá, fú kē zhǐ chū, zài gè gè shí qī de zhī shí xíng zhī jiān cún zài shēn céng duàn liè。 cǐ wài, yóu yú yǔ yán xué jù yòu jiě gòu liú tǎng yú suǒ yòu rén wén xué kē zhōng yǔ yán de tè shū gōng néng, yīn cǐ zài rén wén kē xué yán jiū zhōng, yǔ yán xué dū chǔyú yī gè shí fēn tè shū de wèi zhì: tòu guò duì yǔ yán de yán jiū, zhī shí xíng cóng shēn cáng zhī chù xiǎn xiàn chū lái。

zhè běn shū“ miào yǔ lián zhū, shēn 'ào huì sè, chōng mǎn zhì huì”, rán 'ér jiù shì zhè yàng yī běn shí zú de xué shù lùn zhe, fǔ jīng chū bǎn jí chéng wéi gōng bù yìng qiú de chàng xiāo shū: dì yī bǎn yóu fǎ guó zuì zhù míng de gā lì mǎ chū bǎn shè yú 1966 nián 10 yuè chū bǎn, yìn liǎo 3500 cè, nián dǐ jí gào shòu qìng, cì nián 6 yuè zài bǎn 5000 cè, 7 yuè: 3000, 9 yuè: 3500, 11 yuè: 3500; 67 nián 3 yuè: 4000, 11 yuè: 5000……, jù shuō dào 80 nián dài wéi zhǐ,《 cí yǔ wù》 jǐn zài fǎ guó jiù yìn shuà liǎo yú 10 wàn cè。 duì zhè běn shū de píng jià yě tóng yàng xì jù, píng lùn yì jiàn jīhū jié rán 'èr fēn, bù shì dà jiā chēng sòng, jiù shì fèn rán shēng tǎo, liǎng zào de lǐng jūn rén wù yě gè gè liǎo dé: bèi yù wéi“ zhī shí fènzǐ liáng xīn” de dà zhé xué jiā sà tè shēng chēng zhè běn shū“ yào jiàn gòu yī zhǒng xīn de yì shí xíng tài, jí zī chǎn jiē jí suǒ néng xiū zhù de dǐ yù mǎ kè sī zhù yì de zuì hòu yī dào dī bà”, fǎ guó gòng chǎn dǎng de jī guān zá zhì yě lián xù fā biǎo pī bó wén zhāng; bù guò gèng yòu yì sī de shì, zhè yī cì, tiān zhù jiào pài de zhī shí fènzǐ men tóng sì hū gāi bù gòng dài tiān de gòng chǎn dǎng rén men zhàn dào liǎo tóng yī tiáo zhàn xiàn lǐ: suī rán jìn gōng de fāng shì yòu suǒ bù tóng, dàn zài fǎn duì zhè yī diǎn shàng, liǎng pài dǎo shì xīn yòu qī qī。 dàn fú kē zhè yī fāng de zhèn róng yě háo bù xùn sè: gāng kuí lāi mǔ pāi 'àn 'ér qǐ, tā yú 1967 nián fā biǎo cháng wén tòng chì“ sà tè yī huǒ” duì《 cí yǔ wù》 de zhǐ zé, bìng zhǐ chū zhēng lùn de jiāo diǎn qí shí bìng bù zài yú yì shí xíng tài, ér zài yú fú kē suǒ kāi chuàng de shì yī tiáo zhǎn xīn de sī xiǎng xì pǔ zhī lù, zhè qià qià yòu shì gù shǒu“ rén běn zhù yì” huò“ rén dào zhù yì” de sà tè děng suǒ bù yuàn yì kàn dào bìng lè yì jiā yǐ chǎn chú de。

bù guǎn zěn yàng,《 cí yǔ wù》 wéi fú kē dài lái liǎo jù dà shēng wàng。 bù jiǔ, fú kē yòu yī cì lí kāi liǎo fǎ guó, qián wǎng tū ní sī dà xué jiù rèn zhé xué jiào shòu。 fú kē zài tū ní sī dù guò liǎo 1968 nián 5 yuè yùn dòng de fēng cháo。 zhè shì yī gè“ gé mìng” de kǒu hào hé xíng dòng shí qī biàn jí 'ōu zhōu nǎi zhì shì jiè de shí qī, tū ní sī bào fā liǎo yī xì liè xué shēng yùn dòng, fú kē tóu shēn yú qí zhōng, fā huī liǎo xiāng dāng de yǐng xiǎng。 cǐ hòu, tā de shēn yǐng hé míng zì yě yī zài chū xiàn yú fǎ guó guó nèi yī cì yòu yī cì de yóu xíng、 kàng yì hé qǐng yuàn shū zhōng。

1968 nián 5 yuè shì jiàn cù shǐ fǎ guó jiào yù xíng zhèng dāng jú fǎn sī jiù dà xué zhì dù de quē xiàn, bìng kāi shǐ cèhuà gǎi gé zhī fǎ。 zuò wéi shí yàn, 1968 nián 10 yuè jiān, xīn rèn jiào yù bù cháng 'ài dé jiā fù 'ěr jué dìng zài bā lí shì jiāo de wàn sēn sēn lín xīng jiàn yī zuò xīn dà xué, tā jiāng yōng yòu chōng fēn de zì yóu lái shí yàn gè zhǒng yòu guān dà xué jiào yù tǐ zhì gǎi gé de xīn xiǎng fǎ。 fú kē bèi rèn mìng wéi xīn xué xiào de zhé xué xì zhù rèn。 dàn shì, wàn sēn hěn kuài jiù xiàn rù wú xiū zhǐ de xué shēng bà kè、 yǔ jǐng chá de lín jiē duì zhì nǎi zhì huǒ bào chōng tū zhōng, fú kē de zhé xué xì yě zài jí zuǒ pài de chǎo rǎng shēng zhōng chéng wéi dòng luàn gēn yuán。 zài wàn sēn liǎng nián, shì shǐ fú kē gǎn dào jīn pí lì jìn de liǎng nián。

1972 nián 12 yuè 2 rì, duì fú kē lái jiǎng shì yī gè jù yòu jì niàn yì yì de rì zǐ, zhè yī tiān, tā zǒu shàng liǎo fǎ lán xī xué yuàn gāo gāo de jiǎng tán, zhèng shì jiù rèn fǎ lán xī xué yuàn sī xiǎng tǐ xì shǐ jiào shòu。 jìn rù fǎ lán xī xué yuàn yì wèi zhe dá xué shù dì wèi de diān fēng: zhè shì fǎ guó dà xué jī gòu de“ shèng diàn zhōng de shèng diàn”。

70 nián dài de fú kē jī jí zhì lì yú gè zhǒng shè huì yùn dòng, tā yùn yòng zì jǐ de shēng wàng zhī chí zhǐ zài gǎi shàn fàn rén rén quán zhuàng kuàng de yùn dòng, bìng qīn zì fā qǐ“ jiān yù qíng bào zǔ” yǐ shōu jí zhěng lǐ jiān yù zhì dù rì cháng yùn zuò de xiáng xì guò chéng; tā zài wéi hù yí mín hé nànmín quán yì de qǐng yuàn shū shàng qiān míng; yǔ sà tè yī qǐ chū xí shēng yuán jiān yù bào dòng fàn rén de kàng yì yóu xíng; mào zhe wēi xiǎn qián wǎng xī bān yá kàng yì dú cái zhě fó lǎng gē duì zhèng zhì fàn de sǐ xíng pàn jué……。 suǒ yòu zhè yī qiēdōu cù shǐ tā shēn rù sī kǎo quán lì de shēn céng jié gòu jí yóu cǐ 'ér lái de jiān jìn、 chéng jiè guò chéng de yùn zuò wèn tí。 zhè xiē sī kǎo gòu chéng liǎo tā 70 nián dài zuì zhòng yào yī běn zhe zuò de quán bù zhù tí héng héng《 guī xùn yǔ chéng fá》。

fú kē de zuì hòu yī bù zhù zuò《 xìng shǐ》 de dì yī juàn《 qiú zhī yì zhì》 zài 1976 nián 12 yuè chū bǎn, zhè bù zuò pǐn de mùdì shì yào tàn jiū xìng guān niàn zài lì shǐ zhōng de biàn qiān hé fā zhǎn。 fú kē duì zhè bù xìng de guān niàn shǐ jì yú hòu wàng, bìng yǐ wù qiú wán měi de tài dù jiā yǐ diāo zhuó, dà gāng hé cǎo gǎo gǎi liǎo yī biàn yòu yī biàn, yǐ zhì zuì zhōng wén běn yǔ zuì chū jìhuà xiāngchà shèn dà。 zhè yòu shì yī bù jù zhù, àn zhào fú kē zuì hòu de 'ān pái, quán shū fēn wéi sì juàn, fēn bié wéi《 qiú zhī yí zhì》、《 kuài gǎn de xiǎng yòng》、《 zì wǒ de hē hù》、《 ròu yù de gào shú》。 kě xī de shì, zuò zhě yǒng yuǎn yě kàn bù dào tā chū qí liǎo, 1984 nián 6 yuè 25 rì, fú kē yīn 'ài zī bìng zài bā lí sà lè bèi dì 'ěr yī yuàn bìng shì, zhōng nián 58 suì。

fú kē de sǐ shǐ fǎ guó shàng xià zhèn jīng。 gòng hé guó zǒng lǐ hé jiào yù bù cháng chēng“ fú kē zhī sǐ duó zǒu liǎo dāng dài zuì wěi dà de zhé xué jiā…… fán shì xiǎng lǐ jiě 20 shì jì hòu qī xiàn dài xìng de rén, dū xū yào kǎo lǜ fú kē。”《 shì jiè bào》、《 jiě fàng bào》、《 chén bào》、《 xīn guān chá jiā》 děng bào kān xiāng jì kān fā dà liàng jì niàn wén zhāng。 sī xiǎng jiè de zhòng yào rén wù yě fēn fēn fā biǎo jì niàn wén zì: nián jiàn xué pài dà shī fèi 'ěr nán bù luó dài 'ěr chēng“ fǎ guó shī qù liǎo yī wèi dāng dài zuì guāng cǎi duó mùdì sī xiǎng jiā, yī wèi zuì kāng kǎi dà dù de zhī shí fènzǐ”; qiáo zhì dù méi zé 'ěr de jì niàn wén zhāng gǎn rén fèi fǔ, lǎo rén lǎo lèi zòng héng de tán dào yǐ qián cháng shuō de huà“ wǒ qù shì shí, mǐ xiē 'ěr huì gěi wǒ xiě fù gào。” rán 'ér, shì shí wú qíng, diān dǎo de yù yán gèng jiā shǐ rén bēi cóng xīn lái:“ mǐ xiē 'ěr fú kē qì wǒ 'ér qù, shǐ wǒ gǎn dào shī qù hěn duō dōng xī, bù jǐn shī qù liǎo shēng huó de sè cǎi yě shī qù liǎo shēng huó de nèi róng。”

6 yuè 29 rì shàng wǔ, fú kē de shī cháng hé qīn yǒu zài yī yuàn jǔ xíng liǎo yí tǐ gào bié yí shì, yí shì shàng, yóu fú kē de xué shēng, zhé xué jiā jí 'ěr dé lè cí xuān dú dào wén, zhè duàn huà xuǎn zì fú kē zuì hòu de zhù zuò《 kuài gǎn de xiǎng yòng》, qià zú yǐ gài kuò fú kē zhōng shēn zhuī qiú hé fèn dǒu de lì chéng:

“ zhì yú shuō shì shénme jī fā zhe wǒ, zhè gè wèn tí hěn jiǎn dān。 wǒ xī wàng zài mǒu xiē rén kàn lái zhè yī jiǎn dān dá 'àn běn shēn jiù zú gòu liǎo。 zhè gè dá 'àn jiù shì hàoqí xīn, zhè shì zhǐ rèn hé qíng kuàng xià dū zhí dé wǒ men dài yī diǎn gù zhí dì tīng cóng qí qū shǐ dé hàoqí xīn: tā bù shì nà zhǒng jié lì xī shōu gōng rén rèn shí de dōng xī de hàoqí xīn, ér shì nà zhǒng néng shǐ wǒ men chāo yuè zì wǒ de hàoqí xīn。 shuō chuān liǎo, duì zhī shí de rè qíng, rú guǒ jǐn jǐn dǎo zhì mǒu zhǒng chéng dù de xué shí de zēngzhǎng, ér bù shì yǐ zhè yàng huò nà yàng de fāng shì jìn kě néng shǐ qiú zhī zhě piān lí zì wǒ de huà, nà zhè zhǒng rè qíng hái yòu shénme jià zhí kě yán? zài rén shēng zhōng: rú guǒ rén men jìn yī bù guān chá hé sī kǎo, yòu xiē shí hòu jiù jué duì xū yào tí chū zhè yàng de wèn tí: liǎo jiě rén néng fǒu cǎi qǔ yǔ zì jǐ yuán yòu de sī wéi fāng shì bù tóng de fāng shì sī kǎo, néng fǒu cǎi qǔ yǔ zì jǐ yuán yòu de guān chá fāng shì bù tóng de fāng shì gǎn zhī。…… jīn tiān de zhé xué héng héng wǒ shì zhǐ zhé xué huó dòng héng héng rú guǒ bù shì sī xiǎng duì zì jǐ de pī pàn gōng zuò, nà yòu shì shénme ní? rú guǒ tā bù shì zhì lì yú rèn shí rú hé jí zài duō dà chéng dù shàng néng gòu yǐ bù tóng de fāng shì sī wéi, ér shì zhèng míng yǐ jīng zhī dào de dōng xī, nà me tā yòu shénme yì yì ní?”

mǐ xiē 'ěr · fú kē - chéng jiù

fú kē de zhù yào gōng zuò zǒng shì wéi rào jǐ gè gòng tóng de zǔ chéng bù fēn hé tí mù, tā zuì zhù yào de tí mù shì quán lì hé tā yǔ zhī shí de guān xì( zhī shí de shè huì xué), yǐ jí zhè gè guān xì zài bù tóng de lì shǐ huán jìng zhōng de biǎo xiàn。 tā jiāng lì shǐ fēn huà wéi yī xì liè“ rèn shí”, fú kē jiāng zhè gè rèn shí dìng yì wéi yī gè wén huà nèi yī dìng xíng shì de quán lì fēn bù。

duì fú kē lái shuō, quán lì bù zhǐ shì wù zhì shàng de huò jūn shì shàng de wēi lì, dāng rán tā men shì quán lì de yī gè yuán sù。 duì fú kē lái shuō, quán lì bù shì yī zhǒng gù dìng bù biàn de, kě yǐ zhǎng wò de wèi zhì, ér shì yī zhǒng guàn chuān zhěng gè shè huì de“ néng liàng liú”。 fú kē shuō, néng gòu biǎo xiàn chū lái yòu zhī shí shì quán lì de yī zhǒng lái yuán, yīn wéi zhè yàng de huà nǐ kě yǐ yòu quán wēi dì shuō chū bié rén shì shénme yàng de hé tā men wèishénme shì zhè yàng de。 fú kē bù jiāng quán lì kàn zuò yī zhǒng xíng shì, ér jiāng tā kàn zuò shǐ yòng shè huì jī gòu lái biǎo xiàn yī zhǒng zhēn lǐ 'ér lái jiāng zì jǐ de mùdì shī jiā yú shè huì de bù tóng de fāng shì。

bǐ rú fú kē zài yán jiū jiān yù de lì shǐ de shí hòu tā bù zhǐ kàn kānshǒu de wù lǐ quán lì shì zěn yàng de, tā hái yán jiū tā men shì zěn yàng cóng shè huì shàng dé dào zhè gè quán lì de héng héng jiān yù shì zěn yàng shè jì de, lái shǐ qiú fàn rèn shí dào tā men dào dǐ shì shuí, lái ràng tā men míng jì zhù yī dìng de xíng dòng guī fàn。 tā hái yán jiū liǎo“ zuì fàn” de fā zhǎn, yán jiū liǎo zuì fàn de dìng yì de biàn huà, yóu cǐ tuī dǎo chū quán lì de biàn huàn。

duì fú kē lái shuō,“ zhēn lǐ”( qí shí shì zài mǒu yī lì shǐ huán jìng zhōng bèi dāng zuò zhēn lǐ de shì wù) shì yùn yòng quán lì de jiēguǒ, ér rén zhǐ bù guò shì shǐ yòng quán lì de gōng jù。

fú kē rèn wéi, yǐ kào yī gè zhēn lǐ xì tǒng jiàn lì de quán lì kě yǐ tōng guò tǎo lùn、 zhī shí、 lì shǐ lái bèi zhì yí, tōng guò qiáng diào shēn tǐ, biǎn dī sī kǎo, huò tōng guò yì shù chuàng zào yě kě yǐ duì zhè yàng de quán lì tiǎo zhàn。

fú kē de shū wǎng wǎng xiěde fēi cháng

mǐ xiē 'ěr · fú kē - zuò pǐn jiè shào

《 fēng diān yǔ wén míng》

yīng wén bǎn《 fēng diān yǔ wén míng》《 fēng diān yǔ wén míng》( Histoiredelafolieàl'âgeclassique-Folieetderaison) shì 1961 nián chū bǎn de, tā shì fú kē de dì yī bù zhòng yào de shū, shì tā zài ruì diǎn jiào fǎ yǔ shí xiě de。 tā tǎo lùn liǎo lì shǐ shàng fēng kuáng zhè gè gài niàn shì rú hé fā zhǎn de。

fú kē de fēn xī shǐ yú zhōng shì jì, tā miáo xiě liǎo dāng shí rén men rú hé jiāng má fēng bìng rén guān qǐ lái。 cóng zhè lǐ kāi shǐ tā tàn tǎo liǎo 15 shì jì yú rén chuán de sī xiǎng hé 17 shì jì fǎ guó duì jiān jìn de tū rán xīng qù。 rán hòu tā tàn tǎo liǎo fēng kuáng shì rú hé bèi kàn zuò yī zhǒng nǚ rén yǐn qǐ de bìng de, dāng shí yòu rén rèn wéi nǚ rén de zǐ gōng zài tā men de shēn tǐ zhōu wéi huán rào kě yǐ yǐn qǐ fēng kuáng。 hòu lái fēng kuáng bèi kàn zuò shì líng hún de jí bìng, zuì hòu, suí zhe xī gé méng dé fú luò yī dé fēng kuáng bèi kàn zuò shì yī zhǒng jīng shén bìng。

fú kē hái yòng liǎo xǔ duō shí jiān lái tàn tǎo rén men shì zěn yàng duì dài fēng zǐ de, cóng jiāng fēng zǐ jiē shòu wéi shè huì zhì xù de yī bù fēn dào jiāng tā men kàn zuò bì xū guān bì qǐ lái de rén。 tā yě yán jiū liǎo rén men shì zěn yàng shì tú zhì liáo fēng kuáng de, yóu qí tā tàn tǎo liǎo fěi lì pǔ pí nèi 'ěr hé sài miù 'ěr tú kè de lì zǐ。 tā duàn dìng zhè xiē rén shǐ yòng de fāng fǎ shì cán bào hé cán kù de。 tú kè bǐ rú duì fēng zǐ jìn xíng chéng fá, yī zhí dào tā men xué huì liǎo lái mó fǎng pǔ tōng rén de zuò wéi, shí jì shàng tā shì yòng kǒnghè de fāng shì lái ràng tā men de xíng wéi xiàng pǔ tōng rén。 yǔ cǐ lèi shìde, pí nèi 'ěr shǐ yòng yàn 'è liáo fǎ, bāo kuò shǐ yòng lěng shuǐ yù hé jǐn shēn fú。 zài fú kē kàn lái, zhè zhǒng liáo fǎ shì shǐ yòng chóngfù de bào xíng zhí dào bìng rén jiāng shěn pàn hé chéng fá de xíng shì nèi huà liǎo。

《 cí yǔ wù》

《 cí yǔ wù》( LesMotsetleschoses:unearchéologiedesscienceshumaines) chū bǎn yú 1966 nián, tā zhù yào de lùn diǎn zài yú měi gè lì shǐ jiē duàn dōuyòu yī tào yì yú qián qī de zhī shí xíng gòu guī zé( fú kē chēng zhī wéi rèn shí xíng( épistémè)), ér xiàn dài zhī shí xíng de tè zhēng zé shì yǐ 「 rén 」 zuò wéi yán jiū de zhōng xīn。 jì rán「 rén」 de gài niàn bìng fēi xiān yàn de cún zài, ér shì wǎn jìn zhī shí xíng xíng sù de jiēguǒ, nà me tā yě jiù huì bèi mǒ qù, rú tóng hǎi biān shā tān shàng de yī zhāng liǎn。 zhè běn shū de wèn shì shǐ fú kē chéng wéi yī wèi zhī míng de fǎ guó zhī shí fènzǐ, dàn yě yīn wéi「 rén zhī sǐ」 de jié lùn 'ér bǎo shòu pī píng。 ràng bǎo luó sà tè jiù céng jī yú cǐ diǎn pī pàn cǐ shū wéi xiǎo zī chǎn jiē jí de zuì hòu bì lěi。

《 guī xùn yǔ chéng fá》

mǐ xiē 'ěr · fú kē《 guī xùn yǔ chéng fá》( Surveilleretpunir:naissancedelaprison) chū bǎn yú 1975 nián。 tā tǎo lùn liǎo xiàn dài huà qián de gōng kāi de、 cán kù de tǒng zhì( bǐ rú tōng guò sǐ xíng huò kù xíng) jiàn jiàn zhuǎn biàn wéi yǐn cáng de、 xīn lǐ de tǒng zhì。 fú kē tí dào zì cóng jiān yù bèi fā míng yǐ lái tā bèi kàn zuò shì wéi yī de duì fàn zuì xíng jìng de jiě jué fāng shì。

fú kē zài zhè bù shū zhōng de zhù yào guān diǎn shì duì zuì fàn de chéng fá yǔ fàn zuì shì yī gè xiāng hù guān xì héng héng liǎng zhě hù wéi qián tí tiáo jiàn。

fú kē jiāng xiàn dài shè huì bǐ zuò biān qìn de《 quán jǐng jiān yù》( Panopticon), yī xiǎo pī kānshǒu kě yǐ jiān shì yī dà pī qiú fàn, dàn tā men zì jǐ què bù bèi kàn dào。

chuán tǒng dì wáng tòu guò líng chí zuì fàn、 zhǎn shǒu shì zhòng, yǐ ròu tǐ de zhǎn shì lái xuān shì zì shēn tǒng yù de quán wēi, zhè zhǒng zhí jiē pù rù shī lì zhě yǔ shòu lì zhě de juésè, 16 shì jì jìn rù gǔ diǎn shí dài, fú kē yǐ liǎng gè lì shǐ shì jiàn zuò wéi diǎn fàn, shuō míng guī xùn shǒu duàn de fāng shì yǔ yàng mào wán quán bù tóng yǐ wǎng。 qí yī shì shǔ yì sì nüè yú 'ōu zhōu, wéi liǎo ràng fā shēng shǔ yì de dì qū zāi qíng bù zhì jì xù kuò sàn, zhǐ shì měi hù rén jiā guān jǐn mén hù, bì jū zì shēn zhù suǒ, bù kě zài wèi jīng xǔ kě xià dào gōng gòng kōng jiān liù dā, jiē dào shàng zhǐ yòu chí qiāng de jūn rén yǐ jí gù dìng shí jiànchū lái xún chá、 diǎn míng, tòu guò shū xiě dēng jì, jì lù měi gè jū mín de cún wáng jiāo fù shì cháng jìn xíng chóngxīn shěn hé, guī xùn fāng shì cóng yuán lái zhǎn shì wēihè, zhì xiàn dài zhuǎn biàn chéng yòng kē xué zhī shí、 kē céng zhì dù jìn xíng gè zhǒng fēn pèi 'ān zhì, xiǎn shì guī xùn shǒu duàn de gǎi biàn。

fú kē wú yì jiě shì zuì fàn shì zěn me lái de, huò shì wèihé huì yòu fàn zuì de xíng wéi děng děng qǐ yuán huò shì jiàn fā shēng de yuán yīn děng wèn tí。 tā yào qiáng diào mǒu zhǒng jī zhì cún zài yú nà biān, yuán běn zhǐ shì yào jiāng yī qún rǎo luàn shè huì zhì xù zhě guān qǐ lái, rán zhè jiàn dān chún shì qíng kāi shǐ bèi guān zhù, yán jiū wèihé zhè qún rén zhè me bù tóng, guān chá lú gǔ dà xiǎo、 xiǎo shí hòu shì fǒu bèi nüè dài, kāi shǐ chǎn shēng xīn lǐ xué、 rén kǒu xué、 fàn zuì xué zhè xiē xué wèn, wéi「 zuì fàn」 zhè gè shēn fèn fù jiā gèng duō de yì hán, yě tóng shí jiā yǐ zhù tǐ huà zuì fàn, shì tú ràng rén zhèng shì qiáng diào zhè mìng tí。 zài cóng zhè tào rèn shí, yú jiān yù zhōng tòu guò fǎn fù cāo liàn、 jiǎn chá shěn hé、 zài cāo liàn, bù zhǐ shì yào jiáo zhèng fàn rén, bìng yào fàn rén rèn qīng zì jǐ shì gè zuì fàn, shì yōng yòu piān chā xíng wéi de「 bù zhèng cháng」 rén, suǒ yǐ nǐ zì jǐ yào nǔ lì jiáo zhèng zì jǐ, jiān yù、 jǐng chá dōushì zài「 bāng zhù」 nǐ zuò zhè jiàn shì qíng。 yě jiù shì shuō, zhè tào jī zhì zhōng de shòu lì zhě jì shì zhù tǐ yòu shì kè tǐ, bù zhǐ gào sù zuì fàn nǐ bì xū zuò shèn me, hái huì yào qiú shí shí wèn zì jǐ zhè yàng zuò duì bù duì, bìng qiě rú héwèi zì jǐ de zhè gè zuì fàn shēn fèn, chàn huǐ hé zì wǒ shěn chá。

《 xìng shǐ》

《 xìng shǐ》 zhōng yì běn《 xìng shǐ》( Histoiredelasexualité) yī gòng fēn sān juàn( běn jìhuà liù juàn), dì yī juàn《 rèn zhī de yì zhì》( Lavolontédesavoir), yě shì zuì cháng bèi yǐn yòng de nà yī juàn, shì 1976 nián chū bǎn de, qí zhù tí shì zuì jìn de liǎng gè shì jì zhōng xìng zài quán lì tǒng zhì zhōng suǒ qǐ de zuò yòng。 zhēn duì duì yú fú luò yī dé děng tí chū de wéi duō lì yà shí dài de xìng yā yì, fú kē tí chū zhì yí, zhǐ chū xìng zài 17 shì jì bìng méi yòu yā yì, xiāng fǎn dé dào liǎo jī lì hé zhī chí。 shè huì gòu jiàn liǎo gè zhǒng jī zhì qù qiáng diào hé yǐn yòu rén men tán lùn xìng。 xìng yǔ quán lì hé huà yǔ jǐn mì dì jié hé zài liǎo yī qǐ。 dì 'èr juàn《 kuài gǎn de xiǎng yòng》( L'Usagedesplaisirs) hé dì sān juàn《 guān zhù zì wǒ》( LeSoucidesoi) shì zài fú kē sǐ qián bù jiǔ yú 1984 nián chū bǎn de。 qí zhù yào nèi róng shì gǔ xī là rén hé gǔ luó mǎ rén duì xìng de guān niàn, guān zhù yī zhǒng“ lún lǐ zhé xué”。 cǐ wài fú kē hái jī běn shàng xiě hǎo liǎo yī bù dì sì juàn, qí nèi róng shì jī dū jiào tǒng zhì shí qī duì ròu tǐ yǔ xìng de guān niàn hé duì jī dū jiào de yǐng xiǎng, dàn yīn wéi fú kē tè bié jù jué zài tā sǐ hòu chū bǎn rèn hé shū jí, jiā rén gēn jù tā de yí yuàn zhì jīn wèi chū bǎn tā de wán zhěng bǎn běn。

《 cí yǔ wù》

《 cí yǔ wù》( LesMotsetleschoses:unearchéologiedesscienceshumaines) chū bǎn yú 1966 nián, tā zhù yào de lùn diǎn zài yú měi gè lì shǐ jiē duàn dōuyòu yī tào yì yú qián qī de zhī shí xíng gòu guī zé( fú kē chēng zhī wéi rèn shí xíng( épistémè)), ér xiàn dài zhī shí xíng de tè zhēng zé shì yǐ「 rén」 zuò wéi yán jiū de zhōng xīn。 jì rán「 rén」 de gài niàn bìng fēi xiān yàn de cún zài, ér shì wǎn jìn zhī shí xíng xíng sù de jiēguǒ, nà me tā yě jiù huì bèi mǒ qù, rú tóng hǎi biān shā tān shàng de yī zhāng liǎn。 zhè běn shū de wèn shì shǐ fú kē chéng wéi yī wèi zhī míng de fǎ guó zhī shí fènzǐ, dàn yě yīn wéi「 rén zhī sǐ」 de jié lùn 'ér bǎo shòu pī píng。 ràng bǎo luó sà tè jiù céng jī yú cǐ diǎn pī pàn cǐ shū wéi xiǎo zī chǎn jiē jí de zuì hòu bì lěi。

Foucault is best known for his critical studies of social institutions, most notably psychiatry, medicine, the human sciences, and the prison system, as well as for his work on the history of human sexuality. His writings on power, knowledge, and discourse have been widely discussed and taken up by others. In the 1960s Foucault was associated with structuralism, a movement from which he distanced himself. Foucault also rejected the poststructuralist and postmodernist labels later attributed to him, preferring to classify his thought as a critical history of modernity rooted in Kant. Foucault's project is particularly influenced by Nietzsche; his "genealogy of knowledge" being a direct allusion to Nietzsche's "genealogy of morality". In a late interview he definitively stated: "I am a Nietzschean."

In 2007 Foucault was listed as the most cited intellectual in the humanities by The Times Higher Education Guide.

Biography

Early life

Foucault was born on 15 October 1926 in Poitiers as Paul-Michel Foucault to a notable provincial family. His father, Paul Foucault, was an eminent surgeon and hoped his son would join him in the profession. His early education was a mix of success and mediocrity until he attended the Jesuit Collège Saint-Stanislas, where he excelled. During this period, Poitiers was part of Vichy France and later came under German occupation. After World War II, Foucault was admitted to the prestigious École Normale Supérieure (rue d'Ulm), the traditional gateway to an academic career in the humanities in France.

The École Normale Supérieure

Foucault's personal life during the École Normale was difficult—he suffered from acute depression. As a result, he was taken to see a psychiatrist. During this time, Foucault became fascinated with psychology. He earned a licence (degree equivalent to BA) in psychology, a very new qualification in France at the time, in addition to a degree in philosophy, in 1952. He was involved in the clinical arm of psychology, which exposed him to thinkers such as Ludwig Binswanger.

Foucault was a member of the French Communist Party from 1950 to 1953. He was inducted into the party by his mentor Louis Althusser, but soon became disillusioned with both the politics and the philosophy of the party. Various people, such as historian Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, have reported that Foucault never actively participated in his cell, unlike many of his fellow party members.

Early career

Foucault failed at the agrégation in 1950 but took it again and succeeded the following year. After a brief period lecturing at the École Normale, he took up a position at the Université Lille Nord de France, where from 1953 to 1954 he taught psychology. In 1954 Foucault published his first book, Maladie mentale et personnalité, a work he later disavowed. At this point, Foucault was not interested in a teaching career, and undertook a lengthy exile from France. In 1954 he served France as a cultural delegate to the University of Uppsala in Sweden (a position arranged for him by Georges Dumézil, who was to become a friend and mentor). In 1958 Foucault left Uppsala and briefly held positions at Warsaw University and at the University of Hamburg.

Foucault returned to France in 1960 to complete his doctorate and take up a post in philosophy at the University of Clermont-Ferrand. There he met philosopher Daniel Defert, who would become his lover of twenty years. In 1961 he earned his doctorate by submitting two theses (as is customary in France): a "major" thesis entitled Folie et déraison: Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique (Madness and Insanity: History of Madness in the Classical Age) and a "secondary" thesis that involved a translation of, and commentary on Kant's Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View. Folie et déraison (Madness and Insanity — published in an abridged edition in English as Madness and Civilization and finally published unabridged as "History of Madness" by Routledge in 2006) was extremely well-received. Foucault continued a vigorous publishing schedule. In 1963 he published Naissance de la Clinique (Birth of the Clinic), Raymond Roussel, and a reissue of his 1954 volume (now entitled Maladie mentale et psychologie or, in English, "Mental Illness and Psychology"), which again, he later disavowed.

After Defert was posted to Tunisia for his military service, Foucault moved to a position at the University of Tunis in 1965. He published Les Mots et les choses (The Order of Things) during the height of interest in structuralism in 1966, and Foucault was quickly grouped with scholars such as Jacques Lacan, Claude Lévi-Strauss, and Roland Barthes as the newest, latest wave of thinkers set to topple the existentialism popularized by Jean-Paul Sartre. Foucault made a number of skeptical comments about Marxism, which outraged a number of left wing critics, but later firmly rejected the "structuralist" label. He was still in Tunis during the May 1968 student riots, where he was profoundly affected by a local student revolt earlier in the same year. In the Autumn of 1968 he returned to France, where he published L'archéologie du savoir (The Archaeology of Knowledge) — a methodological response to his critics — in 1969.

Post-1968: as activist

In the aftermath of 1968, the French government created a new experimental university, Paris VIII, at Vincennes and appointed Foucault the first head of its philosophy department in December of that year. Foucault appointed mostly young leftist academics (such as Judith Miller) whose radicalism provoked the Ministry of Education, who objected to the fact that many of the course titles contained the phrase "Marxist-Leninist," and who decreed that students from Vincennes would not be eligible to become secondary school teachers. Foucault notoriously also joined students in occupying administration buildings and fighting with police.

Foucault's tenure at Vincennes was short-lived, as in 1970 he was elected to France's most prestigious academic body, the Collège de France, as Professor of the History of Systems of Thought. His political involvement increased, and his partner Defert joined the ultra-Maoist Gauche Proletarienne (GP). Foucault helped found the Prison Information Group (French: Groupe d'Information sur les Prisons or GIP) to provide a way for prisoners to voice their concerns. This coincided with Foucault's turn to the study of disciplinary institutions, with a book, Surveiller et Punir (Discipline and Punishment), which "narrates" the micro-power structures that developed in Western societies since the eighteenth century, with a special focus on prisons and schools.

Later life

In the late 1970s, political activism in France tailed off with the disillusionment of many left wing intellectuals. A number of young Maoists abandoned their beliefs to become the so-called New Philosophers, often citing Foucault as their major influence, a status Foucault had mixed feelings about. Foucault in this period embarked on a six-volume project The History of Sexuality, which he never completed. Its first volume was published in French as La Volonté de Savoir (1976), then in English as The History of Sexuality: An Introduction (1978). The second and third volumes did not appear for another eight years, and they surprised readers by their subject matter (classical Greek and Latin texts), approach and style, particularly Foucault's focus on the human subject, a concept that some mistakenly believed he had previously neglected.

Foucault began to spend more time in the United States, at the University at Buffalo (where he had lectured on his first ever visit to the United States in 1970) and especially at UC Berkeley. In 1975 he took LSD at Zabriskie Point in Death Valley National Park, later calling it the best experience of his life.

In 1979 Foucault made two tours of Iran, undertaking extensive interviews with political protagonists in support of the new interim government established soon after the Iranian Revolution. His many essays on Iran, published in the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera, only appeared in French in 1994 and then in English in 2005. These essays caused some controversy, with some commentators arguing that Foucault was insufficiently critical of the new regime.

In the philosopher's later years, interpreters of Foucault's work attempted to engage with the problems presented by the fact that the late Foucault seemed in tension with the philosopher's earlier work. When this issue was raised in a 1982 interview, Foucault remarked "When people say, 'Well, you thought this a few years ago and now you say something else,' my answer is… [laughs] 'Well, do you think I have worked hard all those years to say the same thing and not to be changed?'" He refused to identify himself as a philosopher, historian, structuralist, or Marxist, maintaining that "The main interest in life and work is to become someone else that you were not in the beginning." In a similar vein, he preferred not to claim that he was presenting a coherent and timeless block of knowledge; he rather desired his books "to be a kind of tool-box others can rummage through to find a tool they can use however they wish in their own area… I don't write for an audience, I write for users, not readers."

In 1992 James Miller published a biography of Foucault that was greeted with controversy in part due to his claim that Foucault's experiences in the gay sadomasochism community during the time he taught at Berkeley directly influenced his political and philosophical works . Miller's book has largely been rebuked by Foucault scholars as being either simply misdirected, a sordid reading of his life and works, or as a politically driven intentional misreading of Foucault's life and works.

Foucault died of an AIDS-related illness in Paris on 25 June 1984. He was the first high-profile French personality who was reported to have AIDS. Little was known about the disease at the time and there has been some controversy since. In the front-page article of Le Monde announcing his death, there was no mention of AIDS, although it was implied that he died from a massive infection. Prior to his death, Foucault had destroyed most of his manuscripts, and in his will had prohibited the publication of what he might have overlooked.

Works

Madness and Civilization

Main article: Madness and Civilization

The English edition of Madness and Civilization is an abridged version of Folie et déraison: Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique, originally published in 1961. A full English translation titled The History of Madness has since been published by Routledge in 2006. "Folie et deraison" originated as Foucault's doctoral dissertation; this was Foucault's first major book, mostly written while he was the Director of the Maison de France in Sweden. It examines ideas, practices, institutions, art and literature relating to madness in Western history.

Foucault begins his history in the Middle Ages, noting the social and physical exclusion of lepers. He argues that with the gradual disappearance of leprosy, madness came to occupy this excluded position. The ship of fools in the 15th century is a literary version of one such exclusionary practice, namely that of sending mad people away in ships. In 17th century Europe, in a movement Foucault famously calls the "Great Confinement," "unreasonable" members of the population were institutionalised. In the eighteenth century, madness came to be seen as the reverse of Reason, and, finally, in the nineteenth century as mental illness.

Foucault also argues that madness was silenced by Reason, losing its power to signify the limits of social order and to point to the truth. He examines the rise of scientific and "humanitarian" treatments of the insane, notably at the hands of Philippe Pinel and Samuel Tuke who he suggests started the conceptualization of madness as 'mental illness'. He claims that these new treatments were in fact no less controlling than previous methods. Pinel's treatment of the mad amounted to an extended aversion therapy, including such treatments as freezing showers and use of a straitjacket. In Foucault's view, this treatment amounted to repeated brutality until the pattern of judgment and punishment was internalized by the patient.

The Birth of the Clinic

Main article: The Birth of the Clinic

Foucault's second major book, The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception (Naissance de la clinique: une archéologie du regard médical) was published in 1963 in France, and translated to English in 1973. Picking up from Madness and Civilization, The Birth of the Clinic traces the development of the medical profession, and specifically the institution of the clinique (translated as "clinic", but here largely referring to teaching hospitals). Its motif is the concept of the medical regard (translated by Alan Sheridan as "medical gaze"), traditionally limited to small, specialized institutions such as hospitals and prisons, but which Foucault examines as subjecting wider social spaces, governing the population en masse.

Death and The Labyrinth

Main article: Death and The Labyrinth

Death and the Labyrinth: The World of Raymond Roussel was published in 1963, and translated into English in 1986. It is unique, being Foucault's only book-length work on literature. For Foucault this was "by far the book I wrote most easily and with the greatest pleasure." Here, Foucault explores theory, criticism and psychology through the texts of Raymond Roussel, one of the fathers of experimental writing, whose work has been celebrated by the likes of Cocteau, Duchamp, Breton, Robbe-Grillet, Gide and Giacometti.

The Order of Things

Main article: The Order of Things

Foucault's Les Mots et les choses. Une archéologie des sciences humaines was published in 1966. It was translated into English and published by Pantheon Books in 1970 under the title The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. Foucault had preferred L'Ordre des Choses for the original French title, but changed the title as there was already another book of this title. The work broadly aims to provide an anti-humanist excavation of the human sciences, such as sociology and psychology. The book opens with an extended discussion of Diego Velázquez's painting Las Meninas and its complex arrangement of sight-lines, hiddenness and appearance. Then it develops its central thesis: all periods of history have possessed specific underlying conditions of truth that constituted what could be expressed as discourse, for example art, science, culture etc. Foucault argues that these conditions of discourse have changed over time, in major and relatively sudden shifts, from one period's episteme to another. Foucault's Nietzschean critique of Enlightenment values in Les mots et les choses has been very influential to cultural history. It is here Foucault's infamous claims that "man is only a recent invention" and that the "end of man" is at hand. The book made Foucault a prominent intellectual figure in France.

The Archaeology of Knowledge

Main article: The Archaeology of Knowledge

Published in 1969, this volume was Foucault's main excursion into methodology, written as an appendix of sorts to Les Mots et les choses. It makes references to Anglo-American analytical philosophy, particularly speech act theory.

Foucault directs his analysis toward the "statement" (énoncé), the basic unit of discourse. "Statement" has a special meaning in the Archaeology: it denotes what makes propositions, utterances, or speech acts meaningful. In contrast to classic structuralists, Foucault does not believe that the meaning of semantic elements is determined prior to their articulation. In this understanding, statements themselves are not propositions, utterances, or speech acts. Rather, statements constitute a network of rules establishing what is meaningful, and these rules are the preconditions for propositions, utterances, or speech acts to have meaning. However, statements are also 'events', because, like other rules, they appear at some time. Depending on whether or not it complies with these rules of meaning, a grammatically correct sentence may still lack meaning and, inversely, a grammatically incorrect sentence may still be meaningful. Statements depend on the conditions in which they emerge and exist within a field of discourse; the meaning of a statement is reliant on the succession of statements that precede and follow it. Foucault aims his analysis towards a huge organised dispersion of statements, called discursive formations. Foucault reiterates that the analysis he is outlining is only one possible procedure, and that he is not seeking to displace other ways of analysing discourse or render them as invalid.

According to Dreyfus and Rabinow, Foucault not only brackets out issues of truth (cf. Husserl), he also brackets out issues of meaning. Rather than looking for a deeper meaning underneath discourse or looking for the source of meaning in some transcendental subject, Foucault analyzes the discursive and practical conditions for the existence of truth and meaning. To show the principles of meaning and truth production in various discursive formations, he details how truth claims emerge during various epochs on the basis of what was actually said and written during these periods. He particularly describes the Renaissance, the Age of Enlightenment, and the 20th century. He strives to avoid all interpretation and to depart from the goals of hermeneutics. This does not mean that Foucault denounces truth and meaning, but just that truth and meaning depend on the historical discursive and practical means of truth and meaning production. For instance, although they were radically different during Enlightenment as opposed to Modernity, there were indeed meaning, truth and correct treatment of madness during both epochs (Madness and Civilization). This posture allows Foucault to denounce a priori concepts of the nature of the human subject and focus on the role of discursive practices in constituting subjectivity.

Dispensing with finding a deeper meaning behind discourse appears to lead Foucault toward structuralism. However, whereas structuralists search for homogeneity in a discursive entity, Foucault focuses on differences. Instead of asking what constitutes the specificity of European thought he asks what constitutes the differences developed within it and over time. Therefore, as a historical method, he refuses to examine statements outside of their historical context: the discursive formation. The meaning of a statement depends on the general rules that characterise the discursive formation to which it belongs. A discursive formation continually generates new statements, and some of these usher in changes in the discursive formation that may or may not be adopted. Therefore, to describe a discursive formation, Foucault also focuses on expelled and forgotten discourses that never happen to change the discursive formation. Their difference to the dominant discourse also describe it. In this way one can describe specific systems that determine which types of statements emerge. In his Foucault (1986), Deleuze describes The Archaeology of Knowledge as "the most decisive step yet taken in the theory-practice of multiplicities."

Discipline and Punish

Main article: Discipline and Punish

Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison was translated into English in 1977, from the French Surveiller et punir: Naissance de la prison, published in 1975. The book opens with a graphic description of the brutal public execution in 1757 of Robert-François Damiens, who attempted to kill Louis XV. Against this it juxtaposes a colourless prison timetable from just over 80 years later. Foucault then inquires how such a change in French society's punishment of convicts could have developed in such a short time. These are snapshots of two contrasting types of Foucault's "Technologies of Punishment." The first type, "Monarchical Punishment," involves the repression of the populace through brutal public displays of executions and torture. The second, "Disciplinary Punishment," is what Foucault says is practiced in the modern era. Disciplinary punishment gives "professionals" (psychologists, programme facilitators, parole officers, etc.) power over the prisoner, most notably in that the prisoner's length of stay depends on the professionals' judgment. Foucault goes on to argue that Disciplinary punishment leads to self-policing by the populace as opposed to brutal displays of authority from the Monarchical period.

Foucault also compares modern society with Jeremy Bentham's "Panopticon" design for prisons (which was unrealized in its original form, but nonetheless influential): in the Panopticon, a single guard can watch over many prisoners while the guard remains unseen. Ancient prisons have been replaced by clear and visible ones, but Foucault cautions that "visibility is a trap." It is through this visibility, Foucault writes, that modern society exercises its controlling systems of power and knowledge (terms Foucault believed to be so fundamentally connected that he often combined them in a single hyphenated concept, "power-knowledge"). Increasing visibility leads to power located on an increasingly individualized level, shown by the possibility for institutions to track individuals throughout their lives. Foucault suggests that a "carceral continuum" runs through modern society, from the maximum security prison, through secure accommodation, probation, social workers, police, and teachers, to our everyday working and domestic lives. All are connected by the (witting or unwitting) supervision (surveillance, application of norms of acceptable behaviour) of some humans by others.

The History of Sexuality

Main article: The History of Sexuality

Three volumes of The History of Sexuality were published before Foucault's death in 1984. The first and most referenced volume, The Will to Knowledge (previously known as An Introduction in English — Histoire de la sexualité, 1: la volonté de savoir in French) was published in France in 1976, and translated in 1977, focusing primarily on the last two centuries, and the functioning of sexuality as an analytics of power related to the emergence of a science of sexuality (scientia sexualis) and the emergence of biopower in the West. In this volume he attacks the "repressive hypothesis," the widespread belief that we have "repressed" our natural sexual drives, particularly since the nineteenth century. He proposes that what is thought of as "repression" of sexuality actually constituted sexuality as a core feature of human identities, and produced a proliferation of discourse on the subject.

The second two volumes, The Use of Pleasure (Histoire de la sexualite, II: l'usage des plaisirs) and The Care of the Self (Histoire de la sexualité, III: le souci de soi) dealt with the role of sex in Greek and Roman antiquity. Both were published in 1984, the year of Foucault's death, with the second volume being translated in 1985, and the third in 1986. In his lecture series from 1979 to 1980 Foucault extended his analysis of government to its 'wider sense of techniques and procedures designed to direct the behaviour of men', which involved a new consideration of the 'examination of conscience' and confession in early Christian literature. These themes of early Christian literature seemed to dominate Foucault's work, alongside his study of Greek and Roman literature, until the end of his life. However, Foucault's death left the work incomplete, and the planned fourth volume of his History of Sexuality on Christianity was never published. The fourth volume was to be entitled Confessions of the Flesh (Les aveux de la chair). The volume was almost complete before Foucault's death and a copy of it is privately held in the Foucault archive. It cannot be published under the restrictions of Foucault's estate.

Lectures

From 1970 until his death in 1984, from January to March of each year except 1977, Foucault gave a course of public lectures and seminars weekly at the Collège de France as the condition of his tenure as professor there. All these lectures were tape-recorded, and Foucault's transcripts also survive. In 1997 these lectures began to be published in French with eight volumes having appeared so far. So far, seven sets of lectures have appeared in English: Psychiatric Power 1973–1974, Abnormal 1974–1975, Society Must Be Defended 1975–1976, Security, Territory, Population 1977–1978, The Hermeneutics of the Subject 1981–1982, The Birth of Biopolitics 1978-1979 and The Government of Self and Others 1982-1983. Society Must Be Defended and Security, Territory, Population pursued an analysis of the broader relationship between security and biopolitics, explicitly politicizing the question of the birth of man raised in The Order of Things. In Security, Territory, Population, Foucault outlines his theory of governmentality, and demonstrates the distinction between sovereignty, discipline, and governmentality as distinct modalities of state power. He argues that governmental state power can be genealogically linked to the 17th century state philosophy of raison d'etat and, ultimately, to the medieval Christian 'pastoral' concept of power. Notes of some of Foucault's lectures from University of California, Berkeley in 1983 have also appeared as Fearless Speech.

Criticisms

Certain theorists have questioned the extent to which Foucault may be regarded as an ethical 'neo-anarchist', the self-appointed architect of a "new politics of truth", or, to the contrary, a nihilistic and disobligating 'neo-functionalist'. Jean-Paul Sartre, in a review of The Order of Things, described the non-Marxist Foucault as "the last rampart of the bourgeoisie."

Jürgen Habermas has described Foucault as a "crypto-normativist"; covertly reliant on the very Enlightenment principles he attempts to deconstruct. Central to this problem is the way Foucault seemingly attempts to remain both Kantian and Nietzschean in his approach:

Foucault discovers in Kant, as the first philosopher, an archer who aims his arrow at the heart of the most actual features of the present and so opens the discourse of modernity ... but Kant's philosophy of history, the speculation about a state of freedom, about world-citizenship and eternal peace, the interpretation of revolutionary enthusiasm as a sign of historical 'progress toward betterment' - must not each line provoke the scorn of Foucault, the theoretician of power? Has not history, under the stoic gaze of the archaeologist Foucault, frozen into an iceberg covered with the crystals of arbitrary formulations of discourse?

– Habermas Taking Aim at the Heart of the Present 1984,

Richard Rorty has argued that Foucault's so-called 'archaeology of knowledge' is fundamentally negative, and thus fails to adequately establish any 'new' theory of knowledge per se. Rather, Foucault simply provides a few valuable maxims regarding the reading of history:

As far as I can see, all he has to offer are brilliant redescriptions of the past, supplemented by helpful hints on how to avoid being trapped by old historiographical assumptions. These hints consist largely of saying: "do not look for progress or meaning in history; do not see the history of a given activity, of any segment of culture, as the development of rationality or of freedom; do not use any philosophical vocabulary to characterize the essence of such activity or the goal it serves; do not assume that the way this activity is presently conducted gives any clue to the goals it served in the past."

– Rorty Foucault and Epistemology, 1986