|

閱讀福澤諭吉 Fukuzawa Yukichi在百家争鸣的作品!!! |

福澤諭吉(1835年1月10日-1901年2月3日),日本近代重要啓蒙思想傢:出版說明1、教育傢、東京學士會院首任院長、日本著名私立大學慶應義塾大學創立者、明治時代六大教育傢之一,影響了明治維新運動,曾經作為1880年在日本設立的興亞會的顧問。

雖然福澤諭吉本人並沒有受到特定學說的影響而産生一貫的理論架構,福澤諭吉卻是最早將經濟學由英文世界引入日本的人之一。福澤諭吉是將復式記賬法介紹給日本的第一人,將近代保險介紹給日本的也是福澤諭吉。為了表揚福澤對近代日本經濟的貢獻,大藏省理財局將福澤的頭像印在1萬日元的正面上。1984年,大藏省理財局曾計劃將聖德太子的頭像印在十萬日元紙幣上,野口英世的頭像印在五萬日元紙幣上,福澤諭吉的頭像印在一萬日元紙幣上,但十萬元和五萬元紙幣最終沒有發行,福澤諭吉也成為日本最高面額紙幣上的人物。

生平

天保六年十二月十二日(1835年1月10日),福澤諭吉出生於攝津國大坂堂島(今大阪府大阪市福島區)。他出身於德川末期下級武士家庭:出版說明1,當時的豐前國中津藩(今屬九州大分縣中津市)藏屋敷的下等武士福澤百助的次子。由於他出生的當晚,作為儒學傢的父親剛剛獲得《上諭條例》(記錄清朝乾隆帝時期的法令的著作),因此給他取名為“諭吉”。諭吉的父親既從事管理與大坂的商人的貸款業務,也是一位通曉儒學的學者。但是由於身份卑微,在等級制度森嚴的中津藩一直未能有所建樹,終生不得志而溘然逝世。因此,諭吉在日後說“門閥等級制度是父親的敵人”,他本人對封建制度也開始産生懷疑。

諭吉在1歲6個月的時候就失去了父親,回到中津(現在的大分縣)。他與他的兄弟或者當時的普通武士傢子弟不同,並沒有忠孝仁義的觀念,也不敬神佛。他起初也非常厭倦讀書,到了14-15歲的時候,由於周邊環境的壓力,他纔開始學習。不久,他的能力就逐漸積纍,漸漸地開始閱讀各種漢文書籍。

安政元年(1854年),19歲的諭吉前往長崎學習蘭學,成為他人生的轉捩點。由於黑船來航後日本國內對火炮戰術的需求高漲,而學習荷蘭的火炮技術必須要有通曉荷蘭語的人才,諭吉的兄長便建議諭吉學習荷蘭語。此後諭吉拜訪了長崎的火炮專傢山本物次郎,在荷蘭語翻譯的指導下開始學習荷蘭語。

安政二年(1855年),介紹諭吉認識山本的奧平壹岐與諭吉不和,便通知諭吉返回中津。但是,從離開中津那時便不打算再回去的諭吉卻自行經過大坂前往江戶(現東京)。他到大坂後,便去投靠與父親同在中津藩藏屋敷工作的兄長。兄長勸阻他前往江戶,並說服諭吉前往大坂學習蘭學。於是諭吉便來到了緒方洪庵的適塾。這中間,因為患傷寒,曾暫時回到中津休養。

安政三年(1856年),福澤諭吉再次前往大坂求學。同年,由於兄長去世,他成為福澤傢的戶主。但是,他仍然沒有放棄求學,變賣了父親的藏書和部分傢産後,還清了債務,雖然除了母親以外的親戚都表示反對,但是諭吉還是毅然前往大坂。由於他無力支付學費,便從奧平壹岐處藉來便偷偷抄寫的建設工程學的教科書《C.M.H.Pel,Handleiding tot de Kennis der Versterkingskunst,Hertogenbosch 》,並以翻譯該書的名義作為緒方的食客而學習。1857年,諭吉成為適塾的塾長。他在塾中研讀抄寫荷蘭語的原著,並根據書中的理論進行化學實驗等。但是由於他害怕見到血,從來沒有做過放血或者解剖手術。雖然適塾主要是教授醫學,但是諭吉對荷蘭語的學習超過了對醫學的興趣。

安政五年(1858年),福澤諭吉為了擔任在江戶的中津藩邸內設立的蘭學塾的講師,便和古川正雄(當時名為岡本周吉,後改名古川節藏)結伴前往江戶。當時住在築地鐵炮洲的奧平傢的中屋敷,在那裏教授蘭學。這個小規模的蘭學塾後來成為了慶應義塾的前身,因此這一年便被定為慶應義塾大學的創立時間。

安政六年(1859年),諭吉前往橫濱。當時,根據日美修好通商條約,橫濱成為了外國人居留地。但是當地全用英語,學習了荷蘭語的諭吉連招牌的文字都看不懂。從此他痛感學習英語的必要,便開始通過字典等自學英語。

同年鼕,為了交換《日美修好通商條約》的批準文本,日本使團要乘坐美國的軍艦Powhatan號赴美國,日本决定派遣鹹臨丸作為護衛艦。福澤諭吉作為鹹臨丸的軍官木村攝津守的助手,在1860年前往美國。當時鹹臨丸的指揮官是勝海舟。之後,福澤也以在首次看到蒸汽船僅僅7年後就乘坐完全由日本人操縱的軍艦橫渡太平洋而感到自豪。他目擊當時日本在列強環伺欺凌下,國傢獨立受到嚴重威脅,福澤以謀求國傢獨立富強為己任:出版說明1。

他早歲遊歷歐美,受近代科學和西方自由民主思想影響很深,回國以後,他極力介紹西方國傢狀況,傳播自由平等之說,以倡導民權,促進“文明開化”,並鼓勵日本人學習科學,興辦企業,發揚獨立自主精神,以爭取日本民族獨立:出版說明1。雖然福澤已經在書上瞭解了很多美國的事物,但是還是受到了文化差異的震撼。例如他在書中寫道,在日本,幾乎沒有人不知道德川傢康子孫的近況,但是美國人幾乎沒有人瞭解喬治·華盛頓的後代們的生活。(事實上,華盛頓並沒有留下後裔) 福澤還和同行的翻譯中濱萬次郎一起購買了韋伯字典的盜版書帶回國內,成為日後研究的幫助。

回國後,他仍然在鐵炮洲教授課程。但是此時他决定放棄荷蘭語,專教英語,把蘭學塾改變成英學塾。同時也受雇於幕府,從事政府公文的翻譯。據說當時他對於不能理解的英文部分,還需要參考荷蘭語的譯本進行翻譯。回國的當年,福澤還將在美國購買的漢語和英文對譯本詞彙集《華英通語》加入日語譯文,作為《增訂華英通語》出版。這是福澤諭吉最早出版的書籍。在書中,福澤將表示V的發音的假名“ウ”上面加上濁音符號變成“ヴ”,這成為後來日本通行的標註方法。

文久二年(1862年)鼕天,日本派遣以竹內下野守為正使的使節團出使歐洲各國,福澤諭吉也隨之同行。當時也用幕府發給的津貼費買了許多英文書籍帶回日本。他在歐洲對於土地買賣等制度也感受到了文化的差異,並對於許多在書本上無法看到的事物進行調查。例如歐洲人習以為常但日本人前所未聞的醫院、銀行、郵政法、徵兵令、選舉、議會等。

通過這幾次參加海外使團的經歷,福澤痛感在日本普及西學的重要。回國後,他寫作了《西洋事情》等書,開始了對西學的啓蒙運動。當時,他曾作為官員提倡幕府機構的改革,但在1868年(慶應4年)後,便將蘭學塾改名為“慶應義塾”,專心從事教育活動。

晚年

在明治維新後,福澤諭吉繼續大力提倡普及西學。並針對日益高漲的國會設立運動,提出創立英國流的不成文憲法的論調。他在明治十四年(1881年)的明治十四年政變後與政府要人絶交,在1882年創辦日報《時事新報(日語)》,遵循不偏不倚的立場,引導社會輿論。

逝世

明治三十一年(1898年)福澤諭吉因為腦出血而病倒,之後雖然一度康復,但福澤諭吉還是在明治三十四年十二月十五日(1901年2月3日)因為腦中風而溘然長逝,享壽六十六歲。

身後

戒名“大觀院獨立自尊居士”。在葬禮上,遺屬遵從福澤的遺志,婉拒了各方的獻花,但是唯獨默然收下了福澤諭吉的盟友大隈重信送來的喪禮。

思想

福澤諭吉主要的思想特徵是反對封建社會的身份制度。他激烈地抨擊封建時代的專製壓抑。福澤在其著作《勸學篇》第一篇開篇第一句即是“天在人之上不造人,天在人之下不造人”可見其對於封建專製的抨擊和對自由平等的肯定。更在《勸學篇》後續篇章中提倡男女平等,婚姻自由等近代化思想。此外,他也吸收了西方的社會契約論,提出要使國民和政府的力量相對均衡。這種均衡說體現了福澤獨特的政治理念,反映出他並非完全照搬西方的政治學說。此外,福澤在其著作《勸學篇》中強調“一人之自由獨立關係到國傢之自由獨立”。而要達到個人的自由獨立,就必須要具備數學、地理、物理、歷史等等現代科學知識。福澤的代表性語言就是“獨立自尊”,這也成為了他死後的戒名。福澤毫無疑問是明治維新時代的最具影響力的思想傢之一,其著名著作《勸學篇》17篇、《福翁自傳》、《脫亞論》。尤其是《勸學篇》十七篇,在當時的日本幾乎人手一本。

勸學篇原文應為“雖然有句話說天在人之上不造人,天在人之下不造人、但是實際上並無平等之事,有富者亦有貧者,有智者亦有愚者。然其差別如何而來,此即是否具學問之別,各位,一起研究學問吧。”此為勸學原旨,與本篇中引申義有些微出入。

經濟思想

福澤諭吉雖是最早將經濟學由英文世界引入亞洲的人之一(如試將competition譯為競爭),他本人卻沒有受到特定學說的影響而産生一貫的理論架構。在早期所著的《西洋事情》外編的一部分,福澤直接翻譯了美國人Chambers所寫Educational Course之中的政治經濟學部分,故出現了所謂經濟社會由競爭所决定的市場論(“經濟之定則”);在《勸學篇》中也多次提及亞當斯密的自由市場經濟論。而在稍後期的《文明論概略》裏,福澤進一步反對“偽君子”的反競爭論,而強調每個人要有秉著“數理”、“實學”的精神,産生智慧、儉約與正直之心;國傢要從“半開”到文明,經濟發展之訣在於正直地面對營利賺錢的期望。由此可知,後期的福澤在客觀的市場競爭外福澤更強調了人作為行為主體的重要性。福澤指謫,開國之初的日本多進口工業財而出口原物料,長期而言將使整體喪失所謂“製産之利”,主張貿易保護的同時,也呼籲稻農改種桑樹,由自給發展至輸出,以增強日本紡織業的競爭力。其所著《通貨論》,在因“不換紙幣”大行而引緻通貨膨脹的同時,顧到政府貨幣政策的睏難而支持政府的紙幣流通政策;而在鬆方財政後又在報紙上發表續篇,擁護通貨管製論,強調貨幣與貿易市場的連動關係。至於在地租改正的問題上,福澤站在反地主的立場,反對地租(土地稅)輕減政策: 由於佃農的租金由市場供需决定,故地主作為不生産階級所上繳的土地稅若減少,則衹會滿足其貪婪兼併的意願。

脫亞論

福澤諭吉終其一生都致力於在日本弘揚西方文明,介紹西方政治制度以及相應的價值觀。他在《時事新報》發表了著名的短文《脫亞論》,積極地提倡在明治維新後的日本應該放棄中華思想和儒教的精神,而吸收學習西洋文明。基於優勝劣汰的思想,他認定東方文明必定失敗,因此他呼籲與東亞鄰國絶交,避免日本被西方視為與鄰國同樣的“野蠻”之地。他對當時的東亞其他國傢采取蔑視的態度,比如將中日甲午戰爭描述為一場“文野(文明與野蠻)之戰”;認為朝鮮王朝、清朝是“惡友”。故而《脫亞論》又被認為是日本思想界對亞洲的“絶交書”,受到當時歐洲帝國主義流行的影響、主張全盤西化的觀點,甚至被比作軍國主義的始祖,因為西方的侵略思想推進了日本開始跟隨着歐美列強的腳步,也走上對外擴張的道路。

但福澤諭吉對於西洋文明並非沒有取捨。可以說在其自由主義的表象之下,始終貫徹不移的是他的民族主義思想。此後,也有人批評福澤是一位肯定侵略行為的種族歧視主義者。但是,根據平山洋的《福澤諭吉的真實》(文春新書)的文字,其實這應該歸因於《福澤諭吉傳》的作者、《時事新報》的主筆、《福澤全集》的主編石河幹明。

根據平山的論點,雖然福澤批評了中國與朝鮮的政府,但是並不是貶低其民族本身。至於將清朝的士兵稱為“豬玀”等種族歧視的說法,其實是石河將自己的觀點偽造成福澤的說法寫入全集的。但是,對於這種觀點,仍有不少人表示質疑。但根據《脫亞論》,事實上當時福澤認為日本、中國之間如同近鄰。而日本已經將舊的茅草房改建成石房,但中國仍然是茅草房。所以福澤認為應該想方法令中國也改建為石房,不然代表中國的茅草房着火一樣會影響到改建成石房的日本。為了代表日本的房子的安全,日本應該不惜強占還是草房的中國、朝鮮,幫助其改建成石房。而且事實上,福澤甚至還通過出資購買武器來資助過當時朝鮮的政變。

言論

影響

福澤畢生從事教育和著述工作,大力發展日本資本主義和推動民主運動:出版說明1。由於福澤生前居住在慶應義塾的校區內,因此現在在他去世時所在的慶應義塾大學三田校區內設有石碑。戒名是“大觀院獨立自尊居士”,墓地在麻布山善福寺。每年2月3日(福澤諭吉的忌日)被稱為雪池忌,校長會帶領衆多師生前往掃墓。慶應義塾大學在傳統上將創始人福澤諭吉稱呼為“福澤先生”,一般師生間的稱呼則為“〇〇君”。

福澤由於是1萬日元的正面人物而在日本傢喻戶曉。有時候人們也將1萬日元直接叫做“福澤諭吉”、“諭吉”或者“諭吉券”。也因此,有人在數1萬元紙幣的張數時,會以1人、2人的人數來計數。1984年,大藏省理財局曾計劃將聖德太子的頭像印在十萬日元紙幣上,野口英世的頭像印在五萬日元紙幣上,福澤諭吉的頭像印在一萬日元紙幣上,但十萬元和五萬元紙幣最終沒有發行,福澤諭吉也成為日本最高面額紙幣上的人物,野口英世的頭像則於2004年被印在一千日元紙幣上。

福澤也是將會計學的基礎“復式記賬法”介紹給日本的第一人。“藉方”、“貸方”的用語也是福澤首先翻譯的。

首先將近代保險制度介紹給日本的也是福澤諭吉。他在《西洋旅案內》(中譯:西洋旅遊介紹)中介紹了人壽保險、火災保險和意外傷害保險等三種保險制度。

主要著作

福澤著譯很多,共有六十餘種,《文明論概略》和《勸學篇》是他兩部代表性著作,當時暢銷全日本,在日本知識界有很大影響:出版說明1。

- 《勸學篇》

- 《文明論概略》

- 《西洋事情》

- 《日々の教え》

- 《通俗民權論》

- 《通俗國權論》

- 《民情一新》

- 《時事小言》

- 《福翁自傳》

- 《福翁百話》

- 《瘠我慢之說》

- 《丁醜公論》

中文譯本

- 《勸學篇》 群力譯,商務印書館,首次出版年月:1958年,印刷年月:1996年,ISBN 7100020530

- 《文明論概略(漢譯世界學術名著叢書)》 北京編譯社譯,商務印書館,1982年6月北京第3次印刷;1995年3月北京第6次印刷,ISBN 7100013038

- 《福澤諭吉與文明論概略/人之初名著導讀叢書》 鮑成學 劉在平 編著,2001年,中國少年兒童出版社,ISBN 7500755996

- 《福澤諭吉自傳》 馬斌譯,商務印書館,1980年,ISBN 7100014220

- 《福翁百話:福澤諭吉隨筆集》 唐雲譯;張新華譯;蔡院森譯;侯俠譯,三聯書店上海分店,1993年,ISBN 7542605860

- 《福澤諭吉教育論著選/外國教育名著叢書》 王桂主譯,人民教育出版社,2005年,ISBN 7107174630

- 《勸學》,徐雪蓉譯,臺灣臺北市:五南文化出版,二零一三年,國際書號ISBN 9789571172545。

登場作品

- 影視劇

- 風暴花開(1940年、東寶、演:大河內傳次郎)

- 福澤諭吉的少年時代(1958年、NHK、演:森勇)

- 激流 福澤桃介傳(1959年、MBS、演:柳永二郎)

- 明日的鐘聲(1961年、NHK、演:木浪茂 → 前田昌明)

- 巨人 大隈重信(1963年、大映、演:船越英二)

- 榎本武揚(1964年、NHK、演:久米明)

- 天皇的世紀(1971年、ABC、演:大出俊)

- 勝海舟(1974年、NHK大河劇、演:青山良彥)

- 明治群像:海上火輪(1976年、NHK、演:高橋昌也)

- 花神(1977年、NHK大河劇、演:入川保則)

- 告別適塾(1981年、MBS、演:篠田三郎)

- 燃燒青春熱血:福澤諭吉與明治群像(1984年、TX、演:瀧澤修)

- 幕末青春塗鴉:福澤諭吉(195年、TBS、演:中村勘九郎)

- 春之波濤(1985年、NHK大河劇、演:小林桂樹)

- 五棱郭(1988年、NTV、演:中村雅俊)

- 勝海舟(1990年、NTV、演:石原良純)

- 福澤諭吉(1991年、東映、演:柴田恭兵)

- EAST MEETS WEST(1995年、鬆竹、演:橋爪淳)

- 走嚮共和(2003年、CCTV、演:小林竜夫)

- 破天荒力(2008年、Sazanami、演:中村繁之)

- 締創學校(2010年、GO CINEMA、演:宅麻伸)

- 阿淺(2015年、NHK、演:武田鐵矢)

參見

註釋

參考文獻

- 《福澤諭吉與日本近代化》 [日]丸山真男著,區建英譯,學林出版社,1992年,ISBN 7805107534

- 《讓福澤諭吉自己談自己吧!》 [日]井田進也著,中華讀書報,2005年

Fukuzawa Yukichi (福澤 諭吉, January 10, 1835 – February 3, 1901) was a Japanese author, writer, teacher, translator, entrepreneur, journalist, and leader who founded Keio University, Jiji-Shinpō (a newspaper) and the Institute for Study of Infectious Diseases.

Fukuzawa was an early Japanese advocate for reform. Fukuzawa's ideas about the organization of government and the structure of social institutions made a lasting impression on a rapidly changing Japan during the Meiji period.

Fukuzawa is regarded as one of the founders of modern Japan.

Early life

Fukuzawa Yukichi was born into an impoverished low-ranking samurai family of the Okudaira Clan of Nakatsu (now Ōita, Kyushu) in 1835. His family lived in Osaka, the main trading center for Japan at the time. His family was poor following the early death of his father, who was also a Confucian scholar. At the age of 5 he started Han learning, and by the time he turned 14 had studied major writings such as the Analects, Tao Te Ching, Zuo Zhuan and Zhuangzi. Fukuzawa was greatly influenced by his lifelong teacher, Shōzan Shiraishi, who was a scholar of Confucianism and Han learning. When he turned 19 in 1854, shortly after Commodore Matthew C. Perry's arrival in Japan, Fukuzawa's brother (the family patriarch) asked Yukichi to travel to Nagasaki, where the Dutch colony at Dejima was located, in order to enter a school of Dutch studies (rangaku). He instructed Yukichi to learn Dutch so that he might study European cannon designs and gunnery.

Fukuzawa spent the beginning of his walk of life just trying to survive the backbreaking yet dull life of a lower-level samurai in Japan during the Tokugawa period. Although Fukuzawa did travel to Nagasaki, his stay was brief as he quickly began to outshine his host in Nagasaki, Okudaira Iki. Okudaira planned to get rid of Fukuzawa by writing a letter saying that Fukuzawa's mother was ill. Seeing through the fake letter Fukuzawa planned to travel to Edo and continue his studies there because he knew he would not be able to in his home domain, Nakatsu, but upon his return to Osaka, his brother persuaded him to stay and enroll at the Tekijuku school run by physician and rangaku scholar Ogata Kōan. Fukuzawa studied at Tekijuku for three years and became fully proficient in the Dutch language. In 1858, he was appointed official Dutch teacher of his family's domain, Nakatsu, and was sent to Edo to teach the family's vassals there.

The following year, Japan opened up three of its ports to American and European ships, and Fukuzawa, intrigued with Western civilization, traveled to Kanagawa to see them. When he arrived, he discovered that virtually all of the European merchants there were speaking English rather than Dutch. He then began to study English, but at that time, English-Japanese interpreters were rare and dictionaries nonexistent, so his studies were slow.

In 1859, the Tokugawa shogunate sent the first diplomatic mission to the United States. Fukuzawa volunteered his services to Admiral Kimura Yoshitake. Kimura's ship, the Kanrin Maru, arrived in San Francisco, California, in 1860. The delegation stayed in the city for a month, during which time Fukuzawa had himself photographed with an American girl, and also found a Webster's Dictionary, from which he began serious study of the English language.

Political movements

Upon his return in 1860, Fukuzawa became an official translator for the Tokugawa bakufu. Shortly thereafter he brought out his first publication, an English-Japanese dictionary which he called "Kaei Tsūgo" (translated from a Chinese-English dictionary) which was a beginning for his series of later books. In 1862, he visited Europe as one of the two English translators in bakufu's 40-man embassy, the First Japanese Embassy to Europe. During its year in Europe, the Embassy conducted negotiations with France, England, the Netherlands, Prussia, and finally Russia. In Russia, the embassy unsuccessfully negotiated for the southern end of Sakhalin (in Japanese Karafuto).

The information collected during these travels resulted in his famous work Seiyō Jijō (西洋事情, "Things western"), which he published in ten volumes in 1867, 1868 and 1870. The books describe western culture and institutions in simple, easy to understand terms, and they became immediate best-sellers. Fukuzawa was soon regarded as the foremost expert on western civilization, leading him to conclude that his mission in life was to educate his countrymen in new ways of thinking in order to enable Japan to resist European imperialism.

In 1868 he changed the name of the school he had established to teach Dutch to Keio Gijuku, and from then on devoted all his time to education. He had even added Public speaking to the educational system's curriculum. While Keiō's initial identity was that of a private school of Western studies (Keio-gijuku), it expanded and established its first university faculty in 1890. Under the name Keio-Gijuku University, it became a leader in Japanese higher education.

Fukuzawa was also a strong advocate for women’s rights. He often spoke up in favor of equality between husbands and wives, the education of girls as well as boys, and the equal love of daughters and sons. At the same time, he called attention to harmful practices such as women’s inability to own property in their own name and the familial distress that took place when married men took mistresses. However, even Fukuzawa was not willing to propose completely equal rights for men and women; only for husbands and wives. He also stated in his 1899 book New Greater Learning for Women that a good marriage was always the best outcome for a young woman, and according to some of Fukuzawa's personal letters, he discouraged his friends from sending their daughters on to higher education so that they would not become less desirable marriage candidates. While some of Yukichi’s other proposed reforms, such as education reforms, found an eager audience, his ideas about women received a less enthusiastic reception. Many[who?] in Japan were incredibly reluctant to challenge the traditional gender roles, in spite of numerous individuals speaking up in favor of greater gender equality.[citation needed]

After suffering a stroke on January 25, 1901, Fukuzawa Yukichi died on February 3. He was buried at Zenpuku-ji, in the Azabu area of Tokyo. Alumni of Keio-Gijuku University hold a ceremony there every year on February 3.

Works

Fukuzawa's writings may have been the foremost of the Edo period and Meiji period. They played a large role in the introduction of Western culture into Japan.

English-Japanese Dictionary

In 1860, he published English-Japanese Dictionary ("Zōtei Kaei Tsūgo"). It was his first publication. He bought English-Chinese Dictionary ("Kaei Tsūgo") in San Francisco in 1860. He translated it to Japanese and he added the Japanese translations to the original textbook. In his book, he invented the new Japanese characters VU (ヴ) to represent the pronunciation of VU, and VA (ヷ) to represent the pronunciation of VA. For example, the name Beethoven is written as ベートーヴェン in Japanese now.

All the Countries of the World, for Children Written in Verse

His famous textbook Sekai Kunizukushi ("All the Countries of the World, for Children Written in Verse", 1869) became a best seller and was used as an official school textbook. His inspiration for writing the books came when he tried to teach world geography to his sons. At the time there were no textbooks on the subject, so he decided to write one himself. He started by buying a few Japanese geography books for children, named Miyakoji ("City roads") and Edo hōgaku ("Tokyo maps"), and practiced reading them aloud. He then wrote Sekai Kunizukushi in six volumes in the same lyrical style. The first volume covered Asian countries, the second volume detailed African countries, European countries were discussed in the third, South American countries in the fourth, and North American countries and Australia in the fifth. Finally, the sixth volume was an appendix that gave an introduction to world geography.

An Encouragement of Learning

Between 1872 and 1876, he published 17 volumes of Gakumon no Susume ( 學問のすすめ, "An Encouragement of Learning" or more idiomatically "On Studying"). In these texts, Fukuzawa outlines the importance of understanding the principle of equality of opportunity and that study was the key to greatness. He was an avid supporter of education and believed in a firm mental foundation through education and studiousness. In the volumes of Gakumon no Susume, influenced by Elements of Moral Science (1835, 1856 ed.) by Brown University President Francis Wayland, Fukuzawa advocated his most lasting principle, "national independence through personal independence." Through personal independence, an individual does not have to depend on the strength of another. With such a self-determining social morality, Fukuzawa hoped to instill a sense of personal strength among the people of Japan, and through that personal strength, build a nation to rival all others. His understanding was that western society had become powerful relative to other countries at the time because western countries fostered education, individualism (independence), competition and exchange of ideas.

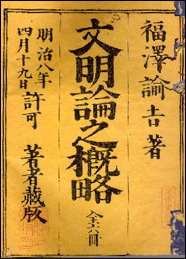

An Outline of a Theory of Civilization

Fukuzawa published many influential essays and critical works. A particularly prominent example is Bunmeiron no Gairyaku ( 文明論之概略, "An Outline of a Theory of Civilization") published in 1875, in which he details his own theory of civilization. It was influenced by Histoire de la civilisation en Europe (1828; Eng. trans in 1846) by François Guizot and History of Civilization in England (1872–1873, 2nd London ed.) by Henry Thomas Buckle. According to Fukuzawa, civilization is relative to time and circumstance, as well in comparison. For example, at the time China was relatively civilized in comparison to some African colonies, and European nations were the most civilized of all.

Colleagues in the Meirokusha intellectual society shared many of Fukuzawa's views, which he published in his contributions to Meiroku Zasshi (Meiji Six Magazine), a scholarly journal he helped publish. In his books and journals, he often wrote about the word "civilization" and what it meant. He advocated a move toward "civilization", by which he meant material and spiritual well-being, which elevated human life to a "higher plane". Because material and spiritual well-being corresponded to knowledge and "virtue", to "move toward civilization" was to advance and pursue knowledge and virtue themselves. He contended that people could find the answer to their life or their present situation from "civilization." Furthermore, the difference between the weak and the powerful and large and small was just a matter of difference between their knowledge and education.

He argued that Japan should not import guns and materials. Instead it should support the acquisition of knowledge, which would eventually take care of the material necessities. He talked of the Japanese concept of being practical or pragmatic (實學, jitsugaku) and the building of things that are basic and useful to other people. In short, to Fukuzawa, "civilization" essentially meant the furthering of knowledge and education.

Criticism

Fukuzawa was later criticized[citation needed] as a supporter of Japanese imperialism because of an essay "Datsu-A Ron" ("Escape from Asia") published in 1885 and posthumously attributed to him, as well as for his support of the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895). Yet, "Datsu-A Ron" was actually a response to a failed attempt by Koreans to organize an effective reform faction.[citation needed] The essay was published as a withdrawal of his support.

According to Fukuzawa Yukichi no Shinjitsu ("The Truth of Fukuzawa Yukichi", 2004) by Yō Hirayama, this view is a misunderstanding due to the influence of Mikiaki Ishikawa, who was the author of a biography of Fukuzawa (1932) and the editor of his Complete Works (1925–1926 and 1933–1934). According to Hirayama, Ishikawa inserted anonymous editorials into the Complete Works, and inserted historically inaccurate material into his biography.

Legacy

Fukuzawa's most important contribution to the reformation effort, though, came in the form of a newspaper called Jiji Shinpō (時事新報, "Current Events"), which he started in 1882, after being prompted by Inoue Kaoru, Ōkuma Shigenobu, and Itō Hirobumi to establish a strong influence among the people, and in particular to transmit to the public the government's views on the projected national assembly, and as reforms began, Fukuzawa, whose fame was already unquestionable, began production of Jiji Shinpo, which received wide circulation, encouraging the people to enlighten themselves and to adopt a moderate political attitude towards the change that was being engineered within the social and political structures of Japan. He translated many books and journals into Japanese on a wide variety of subjects, including chemistry, the arts, military and society, and published many books (in multiple volumes) and journals himself describing Western society, his own philosophy and change, etc.

Fukuzawa was one of the most influential people ever that helped Japan modernize into the country it is today. He never accepted any high position and remained a normal Japanese citizen for his whole life. By the time of his death, he was revered as one of the founders of modern Japan. All of his work was written and was released at a critical juncture in the Japanese society and uncertainty for the Japanese people about their future after the signing of the Unequal treaties, their realization in the weakness of the Japanese government at the time (Tokugawa Shogunate) and its inability to repel the American and European influence. It should also be noted that there were bands of samurai that forcefully opposed the Americans and Europeans and their friends through murder and destruction. Fukuzawa was in danger of his life as a samurai group killed one of his colleagues for advocating policies like those of Fukuzawa. Fukuzawa wrote at a time when the Japanese people were undecided on whether they should be bitter about the American and European forced treaties and imperialism, or to understand the West and move forward. Fukuzawa greatly aided the ultimate success of the pro-modernization forces.

Fukuzawa appears on the current 10,000-yen banknote and has been compared to Benjamin Franklin in the United States. Franklin appears on the similarly-valued $100 bill. Although all other figures appearing on Japanese banknotes changed when the recent redesign was released, Fukuzawa remained on the 10,000-yen note.

Yukichi Fukuzawa's former residence in the city of Nakatsu in Ōita Prefecture is a Nationally Designated Cultural Asset. The house and the Yukichi Fukuzawa Memorial Hall are the major tourist attractions of this city.

Yukichi Fukuzawa was a firm believer that Western education surpassed Japan's. However, he did not like the idea of parliamentary debates. As early as 1860, Yukichi Fukuzawa traveled to Europe and the United States. He believed that the problem in Japan was the undervalued mathematics and science.[citation needed] Also, these suffered from a "lack of the idea of independence". The Japanese conservatives were not happy about Fukuzawa's view of Western education. Since he was a family friend of conservatives, he took their stand to heart. Fukuzawa later came to state that he went a little too far.

One word sums up his entire theme and that is "independence". Yukichi Fukuzawa believed that national independence was the framework to society in the West. However, to achieve this independence, as well as personal independence, Fukuzawa advocated Western learning. He believed that public virtue would increase as people became more educated.

Bibliography

Original Japanese books

- English-Japanese dictionary (増訂華英通語 Zōtei Kaei Tsūgo, 1860)

- Things western (西洋事情 Seiyō Jijō, 1866, 1868 and 1870)

- Rifle instruction book (雷銃操法 Raijyū Sōhō, 1867)

- Guide to travel in the western world (西洋旅案內 Seiyō Tabiannai, 1867)

- Our eleven treaty countries (條約十一國記 Jyōyaku Jyūichi-kokki, 1867)

- Western ways of living: food, clothes, housing (西洋衣食住 Seiyō Isyokujyū, 1867)

- Handbook for soldiers (兵士懐中便覽 Heishi Kaicyū Binran, 1868)

- Illustrated book of physical sciences (訓蒙窮理圖解 Kinmō Kyūri Zukai, 1868)

- Outline of the western art of war (洋兵明鑑 Yōhei Meikan, 1869)

- Pocket almanac of the world (掌中萬國一覽 Shōcyū Bankoku-Ichiran, 1869)

- English parliament (英國議事院談 Eikoku Gijiindan, 1869)

- Sino-British diplomatic relations (清英交際始末 Shin-ei Kosai-shimatsu, 1869)

- All the countries of the world, for children written in verse (世界國盡 Sekai Kunizukushi, 1869)

- Daily lesson for children (ひびのおしえ Hibi no Oshie, 1871) - These books were written for Fukuzawa's first son Ichitarō and second son Sutejirō.

- Book of reading and penmanship for children (啓蒙手習の文 Keimō Tenarai-no-Fumi, 1871)

- Encouragement of learning (學問のすゝめ Gakumon no Susume, 1872–1876)

- Junior book of ethics with many tales from western lands (童蒙教草 Dōmō Oshie-Gusa, 1872)

- Deformed girl (かたわ娘 Katawa Musume, 1872)

- Explanation of the new calendar (改暦弁 Kaireki-Ben, 1873)

- Bookkeeping (帳合之法 Chōai-no-Hō, 1873)

- Maps of Japan for children (日本地圖草紙 Nihon Chizu Sōshi, 1873)

- Elementary reader for children (文字之教 Moji-no-Oshie, 1873)

- How to hold a conference (會議弁 Kaigi-Ben, 1874)

- An Outline of a Theory of Civilization (文明論之概略 Bunmeiron no Gairyaku, 1875)

- Independence of the scholar's mind (學者安心論 Gakusya Anshinron, 1876)

- On decentralization of power, advocating less centralized government in Japan (分權論 Bunkenron, 1877)

- Popular economics (民間經濟録 Minkan Keizairoku, 1877)

- Collected essays of Fukuzawa (福澤文集 Fukuzawa Bunsyū, 1878)

- On currency (通貨論 Tsūkaron, 1878)

- Popular discourse on people's rights (通俗民權論 Tsūzoku Minkenron, 1878)

- Popular discourse on national rights (通俗國權論 Tsūzoku Kokkenron, 1878)

- Transition of people's way of thinking (民情一新 Minjyō Isshin, 1879)

- On national diet (國會論 Kokkairon, 1879)

- Commentary on the current problems (時事小言 Jiji Shōgen, 1881)

- On general trends of the times (時事大勢論 Jiji Taiseiron, 1882)

- On the imperial household (帝室論 Teishitsuron, 1882)

- On armament (兵論 Heiron, 1882)

- On moral training (徳育如何 Tokuiku-Ikan, 1882)

- On the independence of learning (學問之獨立 Gakumon-no Dokuritsu, 1883)

- On the national conscription (全國徵兵論 Zenkoku Cyōheiron, 1884)

- Popular discourse on foreign diplomacy (通俗外交論 Tsūzoku Gaikōron, 1884)

- On Japanese womanhood (日本婦人論 Nihon Fujinron, 1885)

- On men's moral life (士人処世論 Shijin Syoseiron, 1885)

- On moral conduct (品行論 Hinkōron, 1885)

- On association of men and women (男女交際論 Nannyo Kosairon, 1886)

- On Japanese manhood (日本男子論 Nihon Nanshiron, 1888)

- On reverence for the Emperor (尊王論 Sonnōron, 1888)

- Future of the Diet; Origin of the difficulty in the Diet; Word on the public security; On land tax (國會の前途 Kokkai-no Zento; Kokkai Nankyoku-no Yurai; Chian-Syōgen; Chisoron, 1892)

- On business (實業論 Jitsugyōron, 1893)

- One hundred discourses of Fukuzawa (福翁百話 Fukuō Hyakuwa, 1897)

- Foreword to the collected works of Fukuzawa (福澤全集緒言 Fukuzawa Zensyū Cyogen, 1897)

- Fukuzawa sensei's talk on the worldly life (福澤先生浮世談 Fukuzawa Sensei Ukiyodan, 1898)

- Discourses of study for success (修業立志編 Syūgyō Rittishihen, 1898)

- Autobiography of Fukuzawa Yukichi (福翁自伝 Fukuō Jiden, 1899)

- Reproof of "the essential learning for women"; New essential learning for women (女大學評論 Onnadaigaku Hyōron; 新女大學 Shin-Onnadaigaku, 1899)

- More discourses of Fukuzawa (福翁百餘話 Fukuō Hyakuyowa, 1901)

- Commentary on the national problems of 1877; Spirit of manly defiance (明治十年丁醜公論 Meiji Jyūnen Teicyū Kōron; 瘠我慢の説 Yasegaman-no Setsu, 1901)

English translations

- The Autobiography of Yukichi Fukuzawa, Revised translation by Eiichi Kiyooka, with a foreword by Carmen Blacker, NY: Columbia University Press, 1980, ISBN 978-0-231-08373-7

- The Autobiography of Yukichi Fukuzawa, Revised translation by Eiichi Kiyooka, with a foreword by Albert M. Craig, NY: Columbia University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-231-13987-8

- The Thought of Fukuzawa series, (Paperback) Keio University Press

- vol.1 福澤諭吉 (2008), An Outline of a Theory of Civilization, Translation by David A. Dilworth, G. Cameron Hurst, III, ISBN 978-4-7664-1560-5

- vol.2 福澤諭吉 (2012), An Encouragement of Learning, Translation by David A. Dilworth, ISBN 978-4-7664-1684-8

- vol.3 福澤諭吉 (2017), Fukuzawa Yukichi on Women and the Family, Edited and with New and Revised Translations by Helen Ballhatchet, ISBN 978-4-7664-2414-0

- Vol.4 The Autobiography of Fukuzawa Yukichi. Revised translation and with an introduction by Helen Ballhatchet.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Nishikawa (1993)

- ^ a b c d e f Hopper, Helen M. (2005). Fukuzawa Yukichi : from samurai to capitalist. New York: Pearson/Longman. ISBN 978-0321078025. OCLC 54694712.

- ^ Dilworth (2012)

- ^ Dilworth & Hurst (2008)

- ^ Adas, Stearns & Schwartz (1993, p. 36).

- ^ Adas, Stearns & Schwartz (1993, p. 37).

References

- Adas, Michael; Stearns, Peter; Schwartz, Stuart (1993), Turbulent Passage: A Global History of the Twentieth Century, Longman Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-06-501039-8

- Nishikawa, Shunsaku (西川俊作) (1993), "FUKUZAWA YUKICHI (1835-1901)" (PDF), Prospects: The Quarterly Review of Comparative Education, vol. XXIII (no. 3/4): 493–506, doi:10.1007/BF02195131, archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-24 () - French version (Archive)

Further reading

- Lu, David John (2005), Japan: A Documentary History: The Dawn of History to the Late Tokugawa Period, M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 978-1-56324-907-5

- Kitaoka, Shin-ichi (2017), Self-Respect and Independence of Mind: The Challenge of Fukuzawa Yukichi, JAPAN LIBRARY, translated by Vardaman, James M., Tokyo: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture (JPIC), ISBN 978-4-916055-62-0

- Kitaoka, Shin-ichi (March–April 2003), "Pride and Independence: Fukuzawa Yukichi and the Spirit of the Meiji Restoration (Part 1)", Journal of Japanese Trade and Industry, archived from the original on 2003-03-31

- Kitaoka, Shin-ichi (May–June 2003), "Pride and Independence: Fukuzawa Yukichi and the Spirit of the Meiji Restoration (Part 2)", Journal of Japanese Trade and Industry, archived from the original on 2003-05-06

- Albert M. Craig (2009), Civilization and Enlightenment: The Early Thought of Fukuzawa Yukichi (Hardcover ed.), Cambridge: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-03108-1

- Tamaki, Norio (2001), Yukichi Fukuzawa, 1835-1901: The Spirit of Enterprise in Modern Japan (Hardcover ed.), United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-333-80121-5

- (in French) Lefebvre, Isabelle. "La révolution chez Fukuzawa et la notion de jitsugaku Fukuzawa Yukichi sous le regard de Maruyama Masao" (Archive). Cipango. 19 | 2012 : Le Japon et le fait colonial II. pp. 79-91.

- (in French) Maruyama, Masao (丸山眞男). "Introduction aux recherches philosophiques de Fukuzawa Yukichi" (Archive). Cipango. 19 | 2012 : Le Japon et le fait colonial II. pp. 191-217. Translated from Japanese by Isabelle Lefebvre.

- (in Japanese) Original version: Maruyama, Masao. "Fukuzawa ni okeru jitsugaku no tenkai. Fukuzawa Yukichi no tetsugaku kenkyū josetsu" (福澤に於ける「實學」の展開、福澤諭吉の哲學研究序説), March 1947, in Maruyama Masao shū (丸山眞男集), vol. xvi, Tōkyō, Iwanami Shoten, (1997), 2004, pp. 108-131.

- (in French) Fukuzawa Yukichi, L’Appel à l’étude, complete edition, translated from Japanese, annotated and presented by Christian Galan, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, april 2018, 220 p.