阅读米歇尔·福柯 Michel Foucault在百家争鸣的作品!!! | |||||||

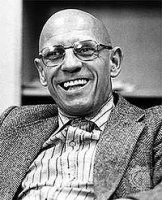

米歇尔·福柯-生平

米歇尔•福柯(Michel Foucault)1926年10月26日出生于法国维艾纳省省会普瓦捷,这是法国西南部的一个宁静小城。他父亲是该城一位受人尊敬的外科医生,母亲也是外科医生的女儿。福柯在普瓦捷完成了小学和中学教育,1945年,他离开家乡前往巴黎参加法国高等师范学校入学考试,并于1946年顺利进入高师学习哲学。1951年通过大中学教师资格会考后,他在梯也尔基金会资助下做了1年研究工作,1952年受聘为里尔大学助教。

早在高师期间,福柯即表现出对心理学和精神病学的极大兴趣,恰好他父母的一位世交雅克琳娜•维尔道(Jacqueline Verdeaus)就是心理学家,而雅克琳娜的丈夫乔治•维尔道则是法国精神分析学大师雅克•拉康的学生。因此,在维尔道夫妇的影响下,福柯对心理学和精神分析学进行了系统深入的学习,并与雅克琳娜一道翻译了瑞士精神病学家宾斯万格尔(Ludwig Binswanger)的著作 《梦与存在》 。书成之后,福柯应雅克琳娜之请为法文本做序,并在1953年复活节之前草就一篇长度超过正文的序言。在这篇长文中,他日后光彩夺目的写作风格已经初露端倪。1954年,这本罕见的序言长过正文的译作由德克雷•德•布鲁沃出版社出版,收入《人类学著作和研究》丛书。同年,福柯发表了自己的第一部专着《精神病与人格》,收入《哲学入门》丛书,由法国大学出版社出版。福柯后来对这部著作加以否定,认为它不成熟,因此,1962年再版时这本书几乎面目全非。

1955年8月,在著名神话学家乔治•杜梅泽尔(Georges Dumezil)的大力推荐下,福柯被瑞典乌普萨拉大学聘为法语教师。在瑞典期间,福柯还兼任法国外交部设立的“法国之家”主任,因此,教学之外,他花了大量时间用于组织各种文化交流活动。在瑞典的3年时间里,福柯开始动手撰写博士论文。得益于乌普萨拉大学图书馆收藏的一大批16世纪以来的医学史档案、书信和各种善本图书,也得益于杜梅泽尔的不断督促和帮助,当福柯离开瑞典时《疯癫与非理智——古典时期的疯癫史》 已经基本完成。

1958年,由于感到教学和工作负担过重对,福柯提出辞职,并于6月间回到巴黎。两个月后,还是在杜梅泽尔的帮助下,同时也因为福柯在瑞典期间表现的出色组织能力,他被法国外交部任命为设在华沙大学内的法国文化中心主任。这年10月,福柯到达波兰,不过他并没有在那儿待太久,原因倒也富于戏剧性:他中了波兰情报机关的美男记。福柯从很早时候起就是同性恋,对此他倒不加掩饰,就个人生活而言,这位老兄显然够得上“风流”的美名。然而50年代正是东西方冷战正酣之时,两方都在挖空心思的相互刺探。恰恰在1959年,法国驻波兰大使馆文化参赞告假,大使本已有心提拔福柯,便一面让他代行参赞职务,一面行文报请正式任命。所以波兰情报机构乘虚而入,风流成性的年轻哲学家合当中计。

离开波兰后,福柯继续他的海外之旅,这一次是目的地是汉堡,仍然是法国文化中心主任。1960年2月,福柯在德国最终完成了他的博士论文。这是一本在厚度和深度上都同样令人匝舌的大书:全书包括附录和参考书目长达943页,考察了自17世纪以来疯癫和精神病观念的流变,详尽梳理了在造型艺术、文学和哲学中体现的疯癫形象形成、转变的过程及其对现代人的意义。按照惯例,申请国家博士学位的应该提交一篇主论文和一篇副论文,福柯因此决定翻译康德的《实用人类学》并以一篇导言作为副论文,虽然这一导言从来没有出版,但福柯研究者们发现,他后来成熟并反映于《词与物》、《知识考古学》中的一些重要概念和思想,在这篇论文中其实已经形成。

应福柯之请,他以前在亨利四世中学的哲学老师,时任巴黎高师校长的让•伊波利特(Jean Hyppolite)欣然同意作副论文的“研究导师”,并推荐著名科学史家、时为巴黎大学哲学系主任的乔治•冈奎莱姆(Georges Conguilhem)担任他的主论文导师。后者对《疯癫史》赞誉有加,并为他写了如下评语“人们会看到这项研究的价值所在,鉴于福柯先生一直关注自文艺复兴时期至今精神病在造型艺术、文学和哲学中反映出来的向现代人提供的多种用途;鉴于他时而理顺、时而又搞乱纷杂的阿莉阿德尼线团,他的论文融分析和综合于一炉,它的严谨,虽然读起来不那么轻松,但却不失睿智之作……因此,我深信福柯先生的研究的重要性是毋庸置疑的。” 1961年5月20日,福柯顺利通过答辩,获得文学博士学位。这篇论文也被评为当年哲学学科的最优秀论文,并颁发给作者一枚铜牌。

还在福柯通过博士论文答辩以前,克莱蒙-费朗大学哲学系新任系主任维也曼在读完《疯癫史》手稿后,即致函尚远在汉堡的作者,希望延聘他为教授。福柯欣然接受,并于1960年10月就任代理教授,1962年5月1日,克莱蒙-费朗大学正式升任福柯为哲学系正教授。在整个60年代,福柯的知名度随着他著作和评论文章的发表而急剧上升:1963年《雷蒙•鲁塞尔》和《临床医学的诞生》 ,1964年《尼采、弗洛伊德、马克思》以及1966年引起极大反响的《词与物》。

这部著作力图构建一种“人文科学考古学”,它“旨在测定在西方文化中,人的探索从何时开始,作为知识对象的人何时出现。” ] 福柯使用“知识型”这一新术语指称特定时期知识产生、运动以及表达的深层框架。通过对文艺复兴以来知识型转变流动的考察,福柯指出,在各个时期的知识型之间存在深层断裂。此外,由于语言学具有解构流淌于所有人文学科中语言的特殊功能,因此在人文科学研究中,语言学都处于一个十分特殊的位置:透过对语言的研究,知识型从深藏之处显现出来。

这本书“妙语连珠,深奥晦涩,充满智慧” ,然而就是这样一本十足的学术论着,甫经出版即成为供不应求的畅销书:第一版由法国最著名的伽利玛出版社于1966年10月出版,印了3500册,年底即告售磬,次年6月再版5000册,7月:3000,9月:3500,11月:3500;67年3月:4000,11月:5000……,据说到80年代为止,《词与物》仅在法国就印刷了逾10万册。对这本书的评价也同样戏剧,评论意见几乎截然二分,不是大加称颂,就是愤然声讨,两造的领军人物也个个了得:被誉为“知识分子良心”的大哲学家萨特声称这本书“要建构一种新的意识形态,即资产阶级所能修筑的抵御马克思主义的最后一道堤坝”,法国共产党的机关杂志也连续发表批驳文章;不过更有意思的是,这一次,天主教派的知识分子们同似乎该不共戴天的共产党人们站到了同一条战线里:虽然进攻的方式有所不同,但在反对这一点上,两派倒是心有期期。但福柯这一方的阵容也毫不逊色:冈奎莱姆拍案而起,他于1967年发表长文痛斥“萨特一伙”对《词与物》的指责,并指出争论的焦点其实并不在于意识形态,而在于福柯所开创的是一条崭新的思想系谱之路,这恰恰又是固守“人本主义”或“人道主义”的萨特等所不愿意看到并乐意加以铲除的。

不管怎样,《词与物》为福柯带来了巨大声望。不久,福柯又一次离开了法国,前往突尼斯大学就任哲学教授。福柯在突尼斯度过了1968年5月运动的风潮。这是一个“革命”的口号和行动时期遍及欧洲乃至世界的时期,突尼斯爆发了一系列学生运动,福柯投身于其中,发挥了相当的影响。此后,他的身影和名字也一再出现于法国国内一次又一次的游行、抗议和请愿书中。

1968年5月事件促使法国教育行政当局反思旧大学制度的缺陷,并开始策划改革之法。作为实验,1968年10月间,新任教育部长艾德加•富尔决定在巴黎市郊的万森森林兴建一座新大学,它将拥有充分的自由来实验各种有关大学教育体制改革的新想法。福柯被任命为新学校的哲学系主任。但是,万森很快就陷入无休止的学生罢课、与警察的临街对峙乃至火爆冲突中,福柯的哲学系也在极左派的吵嚷声中成为动乱根源。在万森两年,是使福柯感到筋疲力尽的两年。

1972年12月2日,对福柯来讲是一个具有纪念意义的日子,这一天,他走上了法兰西学院高高的讲坛,正式就任法兰西学院思想体系史教授。进入法兰西学院意味着达学术地位的颠峰:这是法国大学机构的“圣殿中的圣殿”。

70年代的福柯积极致力于各种社会运动,他运用自己的声望支持旨在改善犯人人权状况的运动,并亲自发起“监狱情报组”以收集整理监狱制度日常运做的详细过程;他在维护移民和难民权益的请愿书上签名;与萨特一起出席声援监狱暴动犯人的抗议游行;冒着危险前往西班牙抗议独裁者佛朗哥对政治犯的死刑判决……。所有这一切都促使他深入思考权力的深层结构及由此而来的监禁、惩戒过程的运作问题。这些思考构成了他70年代最重要一本着作的全部主题——《规训与惩罚》。

福柯的最后一部著作《性史》的第一卷《求知意志》在1976年12月出版,这部作品的目的是要探究性观念在历史中的变迁和发展。福柯对这部性的观念史寄予厚望,并以务求完美的态度加以雕琢,大纲和草稿改了一遍又一遍,以至最终文本与最初计划相差甚大。这又是一部巨著,按照福柯最后的安排,全书分为四卷,分别为《求知遗志》、《快感的享用》、《自我的呵护》、《肉欲的告赎》。可惜的是,作者永远也看不到它出齐了,1984年6月25日,福柯因艾滋病在巴黎萨勒贝蒂尔医院病逝,终年58岁。

福柯的死使法国上下震惊。共和国总理和教育部长称“福柯之死夺走了当代最伟大的哲学家……凡是想理解20世纪后期现代性的人,都需要考虑福柯。” 《世界报 》 、 《解放报》 、《晨报》、《新观察家》等报刊相继刊发大量纪念文章。思想界的重要人物也纷纷发表纪念文字:年鉴学派大师费尔南•布罗代尔称“法国失去了一位当代最光彩夺目的思想家,一位最慷慨大度的知识分子”;乔治•杜梅泽尔的纪念文章感人肺腑,老人老泪纵横的谈到以前常说的话“我去世时,米歇尔会给我写讣告。”然而,事实无情,颠倒的预言更加使人悲从心来:“米歇尔•福柯弃我而去,使我感到失去很多东西,不仅失去了生活的色彩也失去了生活的内容。”

6月29日上午,福柯的师长和亲友在医院举行了遗体告别仪式,仪式上,由福柯的学生,哲学家吉尔•德勒兹宣读悼文,这段话选自福柯最后的著作 《快感的享用》 ,恰足以概括福柯终身追求和奋斗的历程:

“至于说是什么激发着我,这个问题很简单。我希望在某些人看来这一简单答案本身就足够了。这个答案就是好奇心,这是指任何情况下都值得我们带一点固执地听从其驱使得好奇心:它不是那种竭力吸收供人认识的东西的好奇心,而是那种能使我们超越自我的好奇心。说穿了,对知识的热情,如果仅仅导致某种程度的学识的增长,而不是以这样或那样的方式尽可能使求知者偏离自我的话,那这种热情还有什么价值可言?在人生中:如果人们进一步观察和思考,有些时候就绝对需要提出这样的问题:了解人能否采取与自己原有的思维方式不同的方式思考,能否采取与自己原有的观察方式不同的方式感知。……今天的哲学——我是指哲学活动——如果不是思想对自己的批判工作,那又是什么呢?如果它不是致力于认识如何及在多大程度上能够以不同的方式思维,而是证明已经知道的东西,那么它有什么意义呢?”

米歇尔·福柯-成就

福柯的主要工作总是围绕几个共同的组成部分和题目,他最主要的题目是权力和它与知识的关系(知识的社会学),以及这个关系在不同的历史环境中的表现。他将历史分化为一系列“认识”,福柯将这个认识定义为一个文化内一定形式的权力分布。

对福柯来说,权力不只是物质上的或军事上的威力,当然它们是权力的一个元素。对福柯来说,权力不是一种固定不变的,可以掌握的位置,而是一种贯穿整 个社会的“能量流”。福柯说,能够表现出来有知识是权力的一种来源,因为这样的话你可以有权威地说出别人是什么样的和他们为什么是这样的。福柯不将权力看 做一种形式,而将它看做使用社会机构来表现一种真理而来将自己的目的施加于社会的不同的方式。

比如福柯在研究监狱的历史的时候他不只看看守的物理权力是怎样的,他还研究他们是怎样从社会上得到这个权利的——监狱是怎样设计的,来使囚犯认识到他们到底是谁,来让他们铭记住一定的行动规范。他还研究了“罪犯”的发展,研究了罪犯的定义的变化,由此推导出权力的变换。

对福柯来说,“真理”(其实是在某一历史环境中被当作真理的事物)是运用权力的结果,而人只不过是使用权力的工具。

福柯认为,依靠一个真理系统建立的权力可以通过讨论、知识、历史来被质疑,通过强调身体,贬低思考,或通过艺术创造也可以对这样的权力挑战。

福柯的书往往写得非常紧凑,充满了历史典故,尤其是小故事,来加强他的理论的论证。福柯的批评者说他往往在引用历史典故时不够小心,他常常错误地引用一个典故或甚至自己创造典故。

米歇尔·福柯-作品介绍

《疯癫与文明》

英文版《疯癫与文明》《疯癫与文明》 (Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique - Folie et deraison)是1961年出版的,它是福柯的第一部重要的书,是他在瑞典教法语时写的。它讨论了历史上疯狂这个概念是如何发展的。

福柯的分析始于中世纪,他描写了当时人们如何将麻风病人关起来。从这里开始他探讨了15世纪愚人船的思想和17世纪法国对监禁的突然兴趣。然后他探讨了疯狂是如何被看做一种女人引起的病的,当时有人认为女人的子宫在她们的身体周围环绕可以引起疯狂。后来疯狂被看做是灵魂的疾病,最后,随着西格蒙德•弗洛伊德疯狂被看做是一种精神病。

福柯还用了许多时间来探讨人们是怎样对待疯子的,从将疯子接受为社会秩序的一部分到将他们看做必须关闭起来的人。他也研究了人们是怎样试图治疗疯狂的,尤其他探讨了菲利普•皮内尔和塞缪尔•图克的例子。他断定这些人使用的方法是残暴和残酷的。图克比如对疯子进行惩罚,一直到他们学会了来模仿普通人的作为,实际上他是用恐吓的方式来让他们的行为像普通人。与此类似的,皮内尔使用厌恶疗法,包括使用冷水浴和紧身服。在福柯看来,这种疗法是使用重复的暴行直到病人将审判和惩罚的形式内化了。

《词与物》

《词与物》 (Les Mots et les choses: une archéologie des sciences humaines)出版于1966年,它主要的论点在于每个历史阶段都有一套异于前期的知识形构规则(福柯称之为认识型(épistémè)),而现代知识型的特征则是以「人」做为研究的中心。既然「人」的概念并非先验的存在,而是晚近知识型形塑的结果,那么它也就会被抹去,如同海边沙滩上的一张脸。这本书的问世使福柯成为一位知名的法国知识分子,但也因为「人之死」的结论而饱受批评。让•保罗•萨特就曾基于此点批判此书为小资产阶级的最后壁垒。

《规训与惩罚》

米歇尔·福柯《规训与惩罚》 (Surveiller et punir: naissance de la prison)出版于1975年。它讨论了现代化前的公开的、残酷的统治(比如通过死刑或酷刑)渐渐转变为隐藏的、心理的统治。福柯提到自从监狱被发明以来它被看做是唯一的对犯罪行径的解决方式。

福柯在这部书中的主要观点是对罪犯的惩罚与犯罪是一个相互关系——两者互为前提条件。

福柯将现代社会比做边沁的《全景监狱》(Panopticon),一小批看守可以监视一大批囚犯,但他们自己却不被看到。

传统帝王透过凌迟罪犯、斩首示众,以肉体的展示来宣示自身统驭的权威,这种直接曝入施力者与受力者的脚色,16世纪进入古典时代,福柯以两个历史事 件作为典范,说明规驯手段的方式与样貌完全不同以往。其一是鼠疫肆虐于欧洲,为了让发生鼠疫的地区灾情不致继续扩散,指示每户人家关紧门户,闭居自身住 所,不可在未经许可下到公共空间溜搭,街道上只有持枪的军人以及固定时间出来巡察、点名,透过书写登记,记录每个居民的存亡交付市长进行重新审核,规训方 式从原来展示威吓,至现代转变成用科学知识、科层制度进行各种分配安置,显示规讯手段的改变。

福柯无意解释罪犯是怎么来的,或是为何会有犯罪的行为等等起源或事件发生的原因等问题。他要强调某种机制存在于那边,原本只是要将一群扰乱社会秩序 者关起来,然这件单纯事情开始被关注,研究为何这群人这么不同,观察颅骨大小、小时候是否被虐待,开始产生心理学、人口学、犯罪学这些学问,为「罪犯」这 个身份附加更多的意涵,也同时加以主体化罪犯,试图让人正视强调这命题。再从这套认识,于监狱中透过反复操练、检查审核、再操练,不只是要矫正犯人,并要 犯人认清自己是个罪犯,是拥有偏差行为的「不正常」人,所以你自己要努力矫正自己,监狱、警察都是在「帮助」你做这件事情。也就是说,这套机制中的受力者 既是主体又是客体,不只告诉罪犯你必须做甚么,还会要求时时问自己这样做对不对,并且如何为自己的这个罪犯身份,忏悔和自我审查。

《性史》

《性史》中译本《性史》 (Histoire de la sexualité)一共分三卷(本计划六卷),第一卷《认知的意志》(La volonté de savoir), 也是最常被引用的那一卷,是1976年出版的,其主题是最近的两个世纪中性在权力统治中所起的作用。针对对于弗洛伊德等提出的维多利亚时代的性压抑,福柯 提出置疑,指出性在17世纪并没有压抑,相反得到了激励和支持。社会构建了各种机制去强调和引诱人们谈论性。性与权力和话语紧密地结合在了一起。第二卷 《快感的享用》(L'Usage des plaisirs)和第三卷《关注自我》(Le Souci de soi) 是在福柯死前不久于1984年出版的。其主要内容是古希腊人和古罗马人对性的观念,关注一种“伦理哲学”。此外福柯还基本上写好了一部第四卷,其内容是基 督教统治时期对肉体与性的观念和对基督教的影响,但因为福柯特别拒绝在他死后出版任何书籍, 家人根据他的遗愿至今未出版它的完整版本。

《词与物》

《词与物》 (Les Mots et les choses: une archéologie des sciences humaines)出版于1966年,它主要的论点在于每个历史阶段都有一套异于前期的知识形构规则(福柯称之为认识型(épistémè)),而现代知识型的特征则是以「人」做为研究的中心。既然「人」的概念并非先验的存在,而是晚近知识型形塑的结果,那么它也就会被抹去,如同海边沙滩上的一张脸。这本书的问世使福柯成为一位知名的法国知识分子,但也因为「人之死」的结论而饱受批评。让•保罗•萨特就曾基于此点批判此书为小资产阶级的最后壁垒。

Foucault is best known for his critical studies of social institutions, most notably psychiatry, medicine, the human sciences, and the prison system, as well as for his work on the history of human sexuality. His writings on power, knowledge, and discourse have been widely discussed and taken up by others. In the 1960s Foucault was associated with structuralism, a movement from which he distanced himself. Foucault also rejected the poststructuralist and postmodernist labels later attributed to him, preferring to classify his thought as a critical history of modernity rooted in Kant. Foucault's project is particularly influenced by Nietzsche; his "genealogy of knowledge" being a direct allusion to Nietzsche's "genealogy of morality". In a late interview he definitively stated: "I am a Nietzschean."

In 2007 Foucault was listed as the most cited intellectual in the humanities by The Times Higher Education Guide.

Biography

Early life

Foucault was born on 15 October 1926 in Poitiers as Paul-Michel Foucault to a notable provincial family. His father, Paul Foucault, was an eminent surgeon and hoped his son would join him in the profession. His early education was a mix of success and mediocrity until he attended the Jesuit Collège Saint-Stanislas, where he excelled. During this period, Poitiers was part of Vichy France and later came under German occupation. After World War II, Foucault was admitted to the prestigious École Normale Supérieure (rue d'Ulm), the traditional gateway to an academic career in the humanities in France.

The École Normale Supérieure

Foucault's personal life during the École Normale was difficult—he suffered from acute depression. As a result, he was taken to see a psychiatrist. During this time, Foucault became fascinated with psychology. He earned a licence (degree equivalent to BA) in psychology, a very new qualification in France at the time, in addition to a degree in philosophy, in 1952. He was involved in the clinical arm of psychology, which exposed him to thinkers such as Ludwig Binswanger.

Foucault was a member of the French Communist Party from 1950 to 1953. He was inducted into the party by his mentor Louis Althusser, but soon became disillusioned with both the politics and the philosophy of the party. Various people, such as historian Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, have reported that Foucault never actively participated in his cell, unlike many of his fellow party members.

Early career

Foucault failed at the agrégation in 1950 but took it again and succeeded the following year. After a brief period lecturing at the École Normale, he took up a position at the Université Lille Nord de France, where from 1953 to 1954 he taught psychology. In 1954 Foucault published his first book, Maladie mentale et personnalité, a work he later disavowed. At this point, Foucault was not interested in a teaching career, and undertook a lengthy exile from France. In 1954 he served France as a cultural delegate to the University of Uppsala in Sweden (a position arranged for him by Georges Dumézil, who was to become a friend and mentor). In 1958 Foucault left Uppsala and briefly held positions at Warsaw University and at the University of Hamburg.

Foucault returned to France in 1960 to complete his doctorate and take up a post in philosophy at the University of Clermont-Ferrand. There he met philosopher Daniel Defert, who would become his lover of twenty years. In 1961 he earned his doctorate by submitting two theses (as is customary in France): a "major" thesis entitled Folie et déraison: Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique (Madness and Insanity: History of Madness in the Classical Age) and a "secondary" thesis that involved a translation of, and commentary on Kant's Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View. Folie et déraison (Madness and Insanity — published in an abridged edition in English as Madness and Civilization and finally published unabridged as "History of Madness" by Routledge in 2006) was extremely well-received. Foucault continued a vigorous publishing schedule. In 1963 he published Naissance de la Clinique (Birth of the Clinic), Raymond Roussel, and a reissue of his 1954 volume (now entitled Maladie mentale et psychologie or, in English, "Mental Illness and Psychology"), which again, he later disavowed.

After Defert was posted to Tunisia for his military service, Foucault moved to a position at the University of Tunis in 1965. He published Les Mots et les choses (The Order of Things) during the height of interest in structuralism in 1966, and Foucault was quickly grouped with scholars such as Jacques Lacan, Claude Lévi-Strauss, and Roland Barthes as the newest, latest wave of thinkers set to topple the existentialism popularized by Jean-Paul Sartre. Foucault made a number of skeptical comments about Marxism, which outraged a number of left wing critics, but later firmly rejected the "structuralist" label. He was still in Tunis during the May 1968 student riots, where he was profoundly affected by a local student revolt earlier in the same year. In the Autumn of 1968 he returned to France, where he published L'archéologie du savoir (The Archaeology of Knowledge) — a methodological response to his critics — in 1969.

Post-1968: as activist

In the aftermath of 1968, the French government created a new experimental university, Paris VIII, at Vincennes and appointed Foucault the first head of its philosophy department in December of that year. Foucault appointed mostly young leftist academics (such as Judith Miller) whose radicalism provoked the Ministry of Education, who objected to the fact that many of the course titles contained the phrase "Marxist-Leninist," and who decreed that students from Vincennes would not be eligible to become secondary school teachers. Foucault notoriously also joined students in occupying administration buildings and fighting with police.

Foucault's tenure at Vincennes was short-lived, as in 1970 he was elected to France's most prestigious academic body, the Collège de France, as Professor of the History of Systems of Thought. His political involvement increased, and his partner Defert joined the ultra-Maoist Gauche Proletarienne (GP). Foucault helped found the Prison Information Group (French: Groupe d'Information sur les Prisons or GIP) to provide a way for prisoners to voice their concerns. This coincided with Foucault's turn to the study of disciplinary institutions, with a book, Surveiller et Punir (Discipline and Punishment), which "narrates" the micro-power structures that developed in Western societies since the eighteenth century, with a special focus on prisons and schools.

Later life

In the late 1970s, political activism in France tailed off with the disillusionment of many left wing intellectuals. A number of young Maoists abandoned their beliefs to become the so-called New Philosophers, often citing Foucault as their major influence, a status Foucault had mixed feelings about. Foucault in this period embarked on a six-volume project The History of Sexuality, which he never completed. Its first volume was published in French as La Volonté de Savoir (1976), then in English as The History of Sexuality: An Introduction (1978). The second and third volumes did not appear for another eight years, and they surprised readers by their subject matter (classical Greek and Latin texts), approach and style, particularly Foucault's focus on the human subject, a concept that some mistakenly believed he had previously neglected.

Foucault began to spend more time in the United States, at the University at Buffalo (where he had lectured on his first ever visit to the United States in 1970) and especially at UC Berkeley. In 1975 he took LSD at Zabriskie Point in Death Valley National Park, later calling it the best experience of his life.

In 1979 Foucault made two tours of Iran, undertaking extensive interviews with political protagonists in support of the new interim government established soon after the Iranian Revolution. His many essays on Iran, published in the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera, only appeared in French in 1994 and then in English in 2005. These essays caused some controversy, with some commentators arguing that Foucault was insufficiently critical of the new regime.

In the philosopher's later years, interpreters of Foucault's work attempted to engage with the problems presented by the fact that the late Foucault seemed in tension with the philosopher's earlier work. When this issue was raised in a 1982 interview, Foucault remarked "When people say, 'Well, you thought this a few years ago and now you say something else,' my answer is… [laughs] 'Well, do you think I have worked hard all those years to say the same thing and not to be changed?'" He refused to identify himself as a philosopher, historian, structuralist, or Marxist, maintaining that "The main interest in life and work is to become someone else that you were not in the beginning." In a similar vein, he preferred not to claim that he was presenting a coherent and timeless block of knowledge; he rather desired his books "to be a kind of tool-box others can rummage through to find a tool they can use however they wish in their own area… I don't write for an audience, I write for users, not readers."

In 1992 James Miller published a biography of Foucault that was greeted with controversy in part due to his claim that Foucault's experiences in the gay sadomasochism community during the time he taught at Berkeley directly influenced his political and philosophical works . Miller's book has largely been rebuked by Foucault scholars as being either simply misdirected, a sordid reading of his life and works, or as a politically driven intentional misreading of Foucault's life and works.

Foucault died of an AIDS-related illness in Paris on 25 June 1984. He was the first high-profile French personality who was reported to have AIDS. Little was known about the disease at the time and there has been some controversy since. In the front-page article of Le Monde announcing his death, there was no mention of AIDS, although it was implied that he died from a massive infection. Prior to his death, Foucault had destroyed most of his manuscripts, and in his will had prohibited the publication of what he might have overlooked.

Works

Madness and Civilization

Main article: Madness and Civilization

The English edition of Madness and Civilization is an abridged version of Folie et déraison: Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique, originally published in 1961. A full English translation titled The History of Madness has since been published by Routledge in 2006. "Folie et deraison" originated as Foucault's doctoral dissertation; this was Foucault's first major book, mostly written while he was the Director of the Maison de France in Sweden. It examines ideas, practices, institutions, art and literature relating to madness in Western history.

Foucault begins his history in the Middle Ages, noting the social and physical exclusion of lepers. He argues that with the gradual disappearance of leprosy, madness came to occupy this excluded position. The ship of fools in the 15th century is a literary version of one such exclusionary practice, namely that of sending mad people away in ships. In 17th century Europe, in a movement Foucault famously calls the "Great Confinement," "unreasonable" members of the population were institutionalised. In the eighteenth century, madness came to be seen as the reverse of Reason, and, finally, in the nineteenth century as mental illness.

Foucault also argues that madness was silenced by Reason, losing its power to signify the limits of social order and to point to the truth. He examines the rise of scientific and "humanitarian" treatments of the insane, notably at the hands of Philippe Pinel and Samuel Tuke who he suggests started the conceptualization of madness as 'mental illness'. He claims that these new treatments were in fact no less controlling than previous methods. Pinel's treatment of the mad amounted to an extended aversion therapy, including such treatments as freezing showers and use of a straitjacket. In Foucault's view, this treatment amounted to repeated brutality until the pattern of judgment and punishment was internalized by the patient.

The Birth of the Clinic

Main article: The Birth of the Clinic

Foucault's second major book, The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception (Naissance de la clinique: une archéologie du regard médical) was published in 1963 in France, and translated to English in 1973. Picking up from Madness and Civilization, The Birth of the Clinic traces the development of the medical profession, and specifically the institution of the clinique (translated as "clinic", but here largely referring to teaching hospitals). Its motif is the concept of the medical regard (translated by Alan Sheridan as "medical gaze"), traditionally limited to small, specialized institutions such as hospitals and prisons, but which Foucault examines as subjecting wider social spaces, governing the population en masse.

Death and The Labyrinth

Main article: Death and The Labyrinth

Death and the Labyrinth: The World of Raymond Roussel was published in 1963, and translated into English in 1986. It is unique, being Foucault's only book-length work on literature. For Foucault this was "by far the book I wrote most easily and with the greatest pleasure." Here, Foucault explores theory, criticism and psychology through the texts of Raymond Roussel, one of the fathers of experimental writing, whose work has been celebrated by the likes of Cocteau, Duchamp, Breton, Robbe-Grillet, Gide and Giacometti.

The Order of Things

Main article: The Order of Things

Foucault's Les Mots et les choses. Une archéologie des sciences humaines was published in 1966. It was translated into English and published by Pantheon Books in 1970 under the title The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. Foucault had preferred L'Ordre des Choses for the original French title, but changed the title as there was already another book of this title. The work broadly aims to provide an anti-humanist excavation of the human sciences, such as sociology and psychology. The book opens with an extended discussion of Diego Velázquez's painting Las Meninas and its complex arrangement of sight-lines, hiddenness and appearance. Then it develops its central thesis: all periods of history have possessed specific underlying conditions of truth that constituted what could be expressed as discourse, for example art, science, culture etc. Foucault argues that these conditions of discourse have changed over time, in major and relatively sudden shifts, from one period's episteme to another. Foucault's Nietzschean critique of Enlightenment values in Les mots et les choses has been very influential to cultural history. It is here Foucault's infamous claims that "man is only a recent invention" and that the "end of man" is at hand. The book made Foucault a prominent intellectual figure in France.

The Archaeology of Knowledge

Main article: The Archaeology of Knowledge

Published in 1969, this volume was Foucault's main excursion into methodology, written as an appendix of sorts to Les Mots et les choses. It makes references to Anglo-American analytical philosophy, particularly speech act theory.

Foucault directs his analysis toward the "statement" (énoncé), the basic unit of discourse. "Statement" has a special meaning in the Archaeology: it denotes what makes propositions, utterances, or speech acts meaningful. In contrast to classic structuralists, Foucault does not believe that the meaning of semantic elements is determined prior to their articulation. In this understanding, statements themselves are not propositions, utterances, or speech acts. Rather, statements constitute a network of rules establishing what is meaningful, and these rules are the preconditions for propositions, utterances, or speech acts to have meaning. However, statements are also 'events', because, like other rules, they appear at some time. Depending on whether or not it complies with these rules of meaning, a grammatically correct sentence may still lack meaning and, inversely, a grammatically incorrect sentence may still be meaningful. Statements depend on the conditions in which they emerge and exist within a field of discourse; the meaning of a statement is reliant on the succession of statements that precede and follow it. Foucault aims his analysis towards a huge organised dispersion of statements, called discursive formations. Foucault reiterates that the analysis he is outlining is only one possible procedure, and that he is not seeking to displace other ways of analysing discourse or render them as invalid.

According to Dreyfus and Rabinow, Foucault not only brackets out issues of truth (cf. Husserl), he also brackets out issues of meaning. Rather than looking for a deeper meaning underneath discourse or looking for the source of meaning in some transcendental subject, Foucault analyzes the discursive and practical conditions for the existence of truth and meaning. To show the principles of meaning and truth production in various discursive formations, he details how truth claims emerge during various epochs on the basis of what was actually said and written during these periods. He particularly describes the Renaissance, the Age of Enlightenment, and the 20th century. He strives to avoid all interpretation and to depart from the goals of hermeneutics. This does not mean that Foucault denounces truth and meaning, but just that truth and meaning depend on the historical discursive and practical means of truth and meaning production. For instance, although they were radically different during Enlightenment as opposed to Modernity, there were indeed meaning, truth and correct treatment of madness during both epochs (Madness and Civilization). This posture allows Foucault to denounce a priori concepts of the nature of the human subject and focus on the role of discursive practices in constituting subjectivity.

Dispensing with finding a deeper meaning behind discourse appears to lead Foucault toward structuralism. However, whereas structuralists search for homogeneity in a discursive entity, Foucault focuses on differences. Instead of asking what constitutes the specificity of European thought he asks what constitutes the differences developed within it and over time. Therefore, as a historical method, he refuses to examine statements outside of their historical context: the discursive formation. The meaning of a statement depends on the general rules that characterise the discursive formation to which it belongs. A discursive formation continually generates new statements, and some of these usher in changes in the discursive formation that may or may not be adopted. Therefore, to describe a discursive formation, Foucault also focuses on expelled and forgotten discourses that never happen to change the discursive formation. Their difference to the dominant discourse also describe it. In this way one can describe specific systems that determine which types of statements emerge. In his Foucault (1986), Deleuze describes The Archaeology of Knowledge as "the most decisive step yet taken in the theory-practice of multiplicities."

Discipline and Punish

Main article: Discipline and Punish

Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison was translated into English in 1977, from the French Surveiller et punir: Naissance de la prison, published in 1975. The book opens with a graphic description of the brutal public execution in 1757 of Robert-François Damiens, who attempted to kill Louis XV. Against this it juxtaposes a colourless prison timetable from just over 80 years later. Foucault then inquires how such a change in French society's punishment of convicts could have developed in such a short time. These are snapshots of two contrasting types of Foucault's "Technologies of Punishment." The first type, "Monarchical Punishment," involves the repression of the populace through brutal public displays of executions and torture. The second, "Disciplinary Punishment," is what Foucault says is practiced in the modern era. Disciplinary punishment gives "professionals" (psychologists, programme facilitators, parole officers, etc.) power over the prisoner, most notably in that the prisoner's length of stay depends on the professionals' judgment. Foucault goes on to argue that Disciplinary punishment leads to self-policing by the populace as opposed to brutal displays of authority from the Monarchical period.

Foucault also compares modern society with Jeremy Bentham's "Panopticon" design for prisons (which was unrealized in its original form, but nonetheless influential): in the Panopticon, a single guard can watch over many prisoners while the guard remains unseen. Ancient prisons have been replaced by clear and visible ones, but Foucault cautions that "visibility is a trap." It is through this visibility, Foucault writes, that modern society exercises its controlling systems of power and knowledge (terms Foucault believed to be so fundamentally connected that he often combined them in a single hyphenated concept, "power-knowledge"). Increasing visibility leads to power located on an increasingly individualized level, shown by the possibility for institutions to track individuals throughout their lives. Foucault suggests that a "carceral continuum" runs through modern society, from the maximum security prison, through secure accommodation, probation, social workers, police, and teachers, to our everyday working and domestic lives. All are connected by the (witting or unwitting) supervision (surveillance, application of norms of acceptable behaviour) of some humans by others.

The History of Sexuality

Main article: The History of Sexuality

Three volumes of The History of Sexuality were published before Foucault's death in 1984. The first and most referenced volume, The Will to Knowledge (previously known as An Introduction in English — Histoire de la sexualité, 1: la volonté de savoir in French) was published in France in 1976, and translated in 1977, focusing primarily on the last two centuries, and the functioning of sexuality as an analytics of power related to the emergence of a science of sexuality (scientia sexualis) and the emergence of biopower in the West. In this volume he attacks the "repressive hypothesis," the widespread belief that we have "repressed" our natural sexual drives, particularly since the nineteenth century. He proposes that what is thought of as "repression" of sexuality actually constituted sexuality as a core feature of human identities, and produced a proliferation of discourse on the subject.

The second two volumes, The Use of Pleasure (Histoire de la sexualite, II: l'usage des plaisirs) and The Care of the Self (Histoire de la sexualité, III: le souci de soi) dealt with the role of sex in Greek and Roman antiquity. Both were published in 1984, the year of Foucault's death, with the second volume being translated in 1985, and the third in 1986. In his lecture series from 1979 to 1980 Foucault extended his analysis of government to its 'wider sense of techniques and procedures designed to direct the behaviour of men', which involved a new consideration of the 'examination of conscience' and confession in early Christian literature. These themes of early Christian literature seemed to dominate Foucault's work, alongside his study of Greek and Roman literature, until the end of his life. However, Foucault's death left the work incomplete, and the planned fourth volume of his History of Sexuality on Christianity was never published. The fourth volume was to be entitled Confessions of the Flesh (Les aveux de la chair). The volume was almost complete before Foucault's death and a copy of it is privately held in the Foucault archive. It cannot be published under the restrictions of Foucault's estate.

Lectures

From 1970 until his death in 1984, from January to March of each year except 1977, Foucault gave a course of public lectures and seminars weekly at the Collège de France as the condition of his tenure as professor there. All these lectures were tape-recorded, and Foucault's transcripts also survive. In 1997 these lectures began to be published in French with eight volumes having appeared so far. So far, seven sets of lectures have appeared in English: Psychiatric Power 1973–1974, Abnormal 1974–1975, Society Must Be Defended 1975–1976, Security, Territory, Population 1977–1978, The Hermeneutics of the Subject 1981–1982, The Birth of Biopolitics 1978-1979 and The Government of Self and Others 1982-1983. Society Must Be Defended and Security, Territory, Population pursued an analysis of the broader relationship between security and biopolitics, explicitly politicizing the question of the birth of man raised in The Order of Things. In Security, Territory, Population, Foucault outlines his theory of governmentality, and demonstrates the distinction between sovereignty, discipline, and governmentality as distinct modalities of state power. He argues that governmental state power can be genealogically linked to the 17th century state philosophy of raison d'etat and, ultimately, to the medieval Christian 'pastoral' concept of power. Notes of some of Foucault's lectures from University of California, Berkeley in 1983 have also appeared as Fearless Speech.

Criticisms

Certain theorists have questioned the extent to which Foucault may be regarded as an ethical 'neo-anarchist', the self-appointed architect of a "new politics of truth", or, to the contrary, a nihilistic and disobligating 'neo-functionalist'. Jean-Paul Sartre, in a review of The Order of Things, described the non-Marxist Foucault as "the last rampart of the bourgeoisie."

Jürgen Habermas has described Foucault as a "crypto-normativist"; covertly reliant on the very Enlightenment principles he attempts to deconstruct. Central to this problem is the way Foucault seemingly attempts to remain both Kantian and Nietzschean in his approach:

Foucault discovers in Kant, as the first philosopher, an archer who aims his arrow at the heart of the most actual features of the present and so opens the discourse of modernity ... but Kant's philosophy of history, the speculation about a state of freedom, about world-citizenship and eternal peace, the interpretation of revolutionary enthusiasm as a sign of historical 'progress toward betterment' - must not each line provoke the scorn of Foucault, the theoretician of power? Has not history, under the stoic gaze of the archaeologist Foucault, frozen into an iceberg covered with the crystals of arbitrary formulations of discourse?

– Habermas Taking Aim at the Heart of the Present 1984,

Richard Rorty has argued that Foucault's so-called 'archaeology of knowledge' is fundamentally negative, and thus fails to adequately establish any 'new' theory of knowledge per se. Rather, Foucault simply provides a few valuable maxims regarding the reading of history:

As far as I can see, all he has to offer are brilliant redescriptions of the past, supplemented by helpful hints on how to avoid being trapped by old historiographical assumptions. These hints consist largely of saying: "do not look for progress or meaning in history; do not see the history of a given activity, of any segment of culture, as the development of rationality or of freedom; do not use any philosophical vocabulary to characterize the essence of such activity or the goal it serves; do not assume that the way this activity is presently conducted gives any clue to the goals it served in the past."

– Rorty Foucault and Epistemology, 1986