中国经典 》 红楼梦 A Dream of Red Mansions 》

第二回 贾夫人仙逝扬州城 冷子兴演说荣国府 CHAPTER II.

曹雪芹 Cao Xueqin

高鹗 Gao E

CHAPTER II.

贾夫人仙逝扬州城 冷子兴演说荣国府 贾夫人仙逝扬州城 冷子兴演说荣国府

一局输赢料不真,香销茶尽尚逡巡。欲知目下兴衰兆,须问旁观冷眼人。

却说封肃因听见公差传唤,忙出来陪笑启问。那些人只嚷:“快请出甄爷来!"封肃忙陪笑道:“小人姓封,并不姓甄。只有当日小婿姓甄,今已出家一二年了,不知可是问他?"那些公人道:“我们也不知什么‘真’‘假’,因奉太爷之命来问,他既是你女婿,便带了你去亲见太爷面禀,省得乱跑。”说着,不容封肃多言,大家推拥他去了。封家人个个都惊慌,不知何兆。

那天约二更时,只见封肃方回来,欢天喜地。众人忙问端的。他乃说道:“原来本府新升的太爷姓贾名化,本贯胡州人氏,曾与女婿旧日相交。方才在咱门前过去,因见娇杏那丫头买线,所以他只当女婿移住于此。我一一将原故回明,那太爷倒伤感叹息了一回,又问外孙女儿,我说看灯丢了。太爷说:‘不妨,我自使番役务必探访回来。’说了一回话,临走倒送了我二两银子。”甄家娘子听了,不免心中伤感。一宿无话。至次日,早有雨村遣人送了两封银子,四匹锦缎,答谢甄家娘子,又寄一封密书与封肃,转托问甄家娘子要那娇杏作二房。封肃喜的屁滚尿流,巴不得去奉承,便在女儿前一力撺掇成了,乘夜只用一乘小轿,便把娇杏送进去了。雨村欢喜,自不必说,乃封百金赠封肃,外谢甄家娘子许多物事,令其好生养赡,以待寻访女儿下落。封肃回家无话。

却说娇杏这丫鬟,便是那年回顾雨村者。因偶然一顾,便弄出这段事来,亦是自己意料不到之奇缘。谁想他命运两济,不承望自到雨村身边,只一年便生了一子,又半载,雨村嫡妻忽染疾下世,雨村便将他扶侧作正室夫人了。正是:

偶因一着错,便为人上人。

原来,雨村因那年士隐赠银之后,他于十六日便起身入都,至大比之期,不料他十分得意,已会了进士,选入外班,今已升了本府知府。虽才干优长,未免有些贪酷之弊,且又恃才侮上,那些官员皆侧目而视。不上一年,便被上司寻了个空隙,作成一本,参他生情狡猾,擅纂礼仪,大怒,即批革职。该部文书一到,本府官员无不喜悦。那雨村心中虽十分惭恨,却面上全无一点怨色,仍是嘻笑自若,交代过公事,将历年做官积的些资本并家小人属送至原籍,安排妥协,却是自己担风袖月,游览天下胜迹。

那日,偶又游至维扬地面,因闻得今岁鹾政点的是林如海。这林如海姓林名海,表字如海,乃是前科的探花,今已升至兰台寺大夫,本贯姑苏人氏,今钦点出为巡盐御史,到任方一月有余。原来这林如海之祖,曾袭过列侯,今到如海,业经五世。起初时,只封袭三世,因当今隆恩盛德,远迈前代,额外加恩,至如海之父,又袭了一代;至如海,便从科第出身。虽系钟鼎之家,却亦是书香之族。只可惜这林家支庶不盛,子孙有限,虽有几门,却与如海俱是堂族而已,没甚亲支嫡派的。今如海年已四十,只有一个三岁之子,偏又于去岁死了。虽有几房姬妾,奈他命中无子,亦无可如何之事。今只有嫡妻贾氏,生得一女,乳名黛玉,年方五岁。夫妻无子,故爱如珍宝,且又见他聪明清秀,便也欲使他读书识得几个字,不过假充养子之意,聊解膝下荒凉之叹。

雨村正值偶感风寒,病在旅店,将一月光景方渐愈。一因身体劳倦,二因盘费不继,也正欲寻个合式之处,暂且歇下。幸有两个旧友,亦在此境居住,因闻得鹾政欲聘一西宾,雨村便相托友力,谋了进去,且作安身之计。妙在只一个女学生,并两个伴读丫鬟,这女学生年又小,身体又极怯弱,工课不限多寡,故十分省力。堪堪又是一载的光阴,谁知女学生之母贾氏夫人一疾而终。女学生侍汤奉药,守丧尽哀,遂又将辞馆别图。林如海意欲令女守制读书,故又将他留下。近因女学生哀痛过伤,本自怯弱多病的,触犯旧症,遂连日不曾上学。雨村闲居无聊,每当风日晴和,饭后便出来闲步。

这日,偶至郭外,意欲赏鉴那村野风光。忽信步至一山环水旋,茂林深竹之处,隐隐的有座庙宇,门巷倾颓,墙垣朽败,门前有额,题着"智通寺"三字,门旁又有一副旧破的对联,曰

身后有余忘缩手,眼前无路想回头。雨村看了,因想到:“这两句话,文虽浅近,其意则深。我也曾游过些名山大刹,倒不曾见过这话头,其中想必有个翻过筋斗来的亦未可知,何不进去试试。”想着走入,只有一个龙钟老僧在那里煮粥。雨村见了,便不在意。及至问他两句话,那老僧既聋且昏,齿落舌钝,所答非所问。

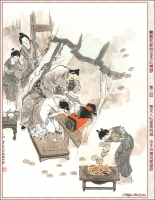

雨村不耐烦,便仍出来,意欲到那村肆中沽饮三杯,以助野趣,于是款步行来。将入肆门,只见座上吃酒之客有一人起身大笑,接了出来,口内说:“奇遇,奇遇。”雨村忙看时,此人是都中在古董行中贸易的号冷子兴者,旧日在都相识。雨村最赞这冷子兴是个有作为大本领的人,这子兴又借雨村斯文之名,故二人说话投机,最相契合。雨村忙笑问道:“老兄何日到此?弟竟不知。今日偶遇,真奇缘也。”子兴道:“去年岁底到家,今因还要入都,从此顺路找个敝友说一句话,承他之情,留我多住两日。我也无紧事,且盘桓两日,待月半时也就起身了。今日敝友有事,我因闲步至此,且歇歇脚,不期这样巧遇!"一面说,一面让雨村同席坐了,另整上酒肴来。二人闲谈漫饮,叙些别后之事。

雨村因问:“近日都中可有新闻没有?"子兴道:“倒没有什么新闻,倒是老先生你贵同宗家,出了一件小小的异事。”雨村笑道:“弟族中无人在都,何谈及此?"子兴笑道:“你们同姓,岂非同宗一族?"雨村问是谁家。子兴道:“荣国府贾府中,可也玷辱了先生的门楣么?"雨村笑道:“原来是他家。若论起来,寒族人丁却不少,自东汉贾复以来,支派繁盛,各省皆有,谁逐细考查得来?若论荣国一支,却是同谱。但他那等荣耀,我们不便去攀扯,至今故越发生疏难认了。”子兴叹道:“老先生休如此说。如今的这宁荣两门,也都萧疏了,不比先时的光景。”雨村道:“当日宁荣两宅的人口也极多,如何就萧疏了?"冷子兴道:“正是,说来也话长。”雨村道:“去岁我到金陵地界,因欲游览六朝遗迹,那日进了石头城,从他老宅门前经过。街东是宁国府,街西是荣国府,二宅相连,竟将大半条街占了。大门前虽冷落无人,隔着围墙一望,里面厅殿楼阁,也还都峥嵘轩峻,就是后一带花园子里面树木山石,也还都有蓊蔚洇润之气,那里象个衰败之家?"冷子兴笑道:“亏你是进士出身,原来不通!古人有云:‘百足之虫,死而不僵。’如今虽说不及先年那样兴盛,较之平常仕宦之家,到底气象不同。如今生齿日繁,事务日盛,主仆上下,安富尊荣者尽多,运筹谋画者无一,其日用排场费用,又不能将就省俭,如今外面的架子虽未甚倒,内囊却也尽上来了。这还是小事。更有一件大事:谁知这样钟鸣鼎食之家,翰墨诗书之族,如今的儿孙,竟一代不如一代了!"雨村听说,也纳罕道:“这样诗礼之家,岂有不善教育之理?别门不知,只说这宁,荣二宅,是最教子有方的。”

子兴叹道:“正说的是这两门呢。待我告诉你:当日宁国公与荣国公是一母同胞弟兄两个。宁公居长,生了四个儿子。宁公死后,贾代化袭了官,也养了两个儿子:长名贾敷,至八九岁上便死了,只剩了次子贾敬袭了官,如今一味好道,只爱烧丹炼汞,余者一概不在心上。幸而早年留下一子,名唤贾珍,因他父亲一心想作神仙,把官倒让他袭了。他父亲又不肯回原籍来,只在都中城外和道士们胡羼。这位珍爷倒生了一个儿子,今年才十六岁,名叫贾蓉。如今敬老爹一概不管。这珍爷那里肯读书,只一味高乐不了,把宁国府竟翻了过来,也没有人敢来管他。再说荣府你听,方才所说异事,就出在这里。自荣公死后,长子贾代善袭了官,娶的也是金陵世勋史侯家的小姐为妻,生了两个儿子:长子贾赦,次子贾政。如今代善早已去世,太夫人尚在,长子贾赦袭着官,次子贾政,自幼酷喜捕潦*,祖父最疼,原欲以科甲出身的,不料代善临终时遗本一上,皇上因恤先臣,即时令长子袭官外,问还有几子,立刻引见,遂额外赐了这政老爹一个主事之衔,令其入部习学,如今现已升了员外郎了。这政老爹的夫人王氏,头胎生的公子,名唤贾珠,十四岁进学,不到二十岁就娶了妻生了子,一病死了。第二胎生了一位小姐,生在大年初一,这就奇了,不想后来又生一位公子,说来更奇,一落胎胞,嘴里便衔下一块五彩晶莹的玉来,上面还有许多字迹,就取名叫作宝玉。你道是新奇异事不是?”

雨村笑道:“果然奇异。只怕这人来历不小。”子兴冷笑道:“万人皆如此说,因而乃祖母便先爱如珍宝。那年周岁时,政老爹便要试他将来的志向,便将那世上所有之物摆了无数,与他抓取。谁知他一概不取,伸手只把些脂粉钗环抓来。政老爹便大怒了,说:“‘将来酒色之徒耳!’因此便大不喜悦。独那史老太君还是命根一样。说来又奇,如今长了七八岁,虽然淘气异常,但其聪明乖觉处,百个不及他一个。说起孩子话来也奇怪,他说:‘女儿是水作的骨肉,男人是泥作的骨肉。我见了女儿,我便清爽,见了男子,便觉浊臭逼人。’你道好笑不好笑?将来色鬼无疑了!"雨村罕然厉色忙止道:“非也!可惜你们不知道这人来历。大约政老前辈也错以淫魔色鬼看待了。若非多读书识事,加以致知格物之功,悟道参玄之力,不能知也。”

子兴见他说得这样重大,忙请教其端。雨村道:“天地生人,除大仁大恶两种,余者皆无大异。若大仁者,则应运而生,大恶者,则应劫而生。运生世治,劫生世危。尧,舜,禹,汤,文,武,周,召,孔,孟,董,韩,周,程,张,朱,皆应运而生者。蚩尤,共工,桀,纣,始皇,王莽,曹操,桓温,安禄山,秦桧等,皆应劫而生者。大仁者,修治天下,大恶者,挠乱天下。清明灵秀,天地之正气,仁者之所秉也,残忍乖僻,天地之邪气,恶者之所秉也。今当运隆祚永之朝,太平无为之世,清明灵秀之气所秉者,上至朝廷,下及草野,比比皆是。所余之秀气,漫无所归,遂为甘露,为和风,洽然溉及四海。彼残忍乖僻之邪气,不能荡溢于光天化日之中,遂凝结充塞于深沟大壑之内,偶因风荡,或被云催,略有摇动感发之意,一丝半缕误而泄出者,偶值灵秀之气适过,正不容邪,邪复妒正,两不相下,亦如风水雷电,地中既遇,既不能消,又不能让,必至搏击掀发后始尽。故其气亦必赋人,发泄一尽始散。使男女偶秉此气而生者,在上则不能成仁人君子,下亦不能为大凶大恶。置之于万万人中,其聪俊灵秀之气,则在万万人之上,其乖僻邪谬不近人情之态,又在万万人之下。若生于公侯富贵之家,则为情痴情种,若生于诗书清贫之族,则为逸士高人,纵再偶生于薄祚寒门,断不能为走卒健仆,甘遭庸人驱制驾驭,必为奇优名倡。如前代之许由,陶潜,阮籍,嵇康,刘伶,王谢二族,顾虎头,陈后主,唐明皇,宋徽宗,刘庭芝,温飞卿,米南宫,石曼卿,柳耆卿,秦少游,近日之倪云林,唐伯虎,祝枝山,再如李龟年,黄幡绰,敬新磨,卓文君,红拂,薛涛,崔莺,朝云之流,此皆易地则同之人也。”

子兴道:“依你说,‘成则王侯败则贼了。’"雨村道:“正是这意。你还不知,我自革职以来,这两年遍游各省,也曾遇见两个异样孩子。所以,方才你一说这宝玉,我就猜着了八九亦是这一派人物。不用远说,只金陵城内,钦差金陵省体仁院总裁甄家,你可知么?"子兴道:“谁人不知!这甄府和贾府就是老亲,又系世交。两家来往,极其亲热的。便在下也和他家来往非止一日了。”

雨村笑道:“去岁我在金陵,也曾有人荐我到甄府处馆。我进去看其光景,谁知他家那等显贵,却是个富而好礼之家,倒是个难得之馆。但这一个学生,虽是启蒙,却比一个举业的还劳神。说起来更可笑,他说:‘必得两个女儿伴着我读书,我方能认得字,心里也明白,不然我自己心里糊涂。’又常对跟他的小厮们说:‘这女儿两个字,极尊贵,极清净的,比那阿弥陀佛,元始天尊的这两个宝号还更尊荣无对的呢!你们这浊口臭舌,万不可唐突了这两个字,要紧。但凡要说时,必须先用清水香茶漱了口才可,设若失错,便要凿牙穿腮等事。’其暴虐浮躁,顽劣憨痴,种种异常。只一放了学,进去见了那些女儿们,其温厚和平,聪敏文雅,竟又变了一个。因此,他令尊也曾下死笞楚过几次,无奈竟不能改。每打的吃疼不过时,他便‘姐姐’‘妹妹’乱叫起来。后来听得里面女儿们拿他取笑:‘因何打急了只管叫姐妹做甚?莫不是求姐妹去说情讨饶?你岂不愧些!’他回答的最妙。他说:‘急疼之时,只叫‘姐姐’妹妹’字样,或可解疼也未可知,因叫了一声,便果觉不疼了,遂得了秘法:每疼痛之极,便连叫姐妹起来了。’你说可笑不可笑?也因祖母溺爱不明,每因孙辱师责子,因此我就辞了馆出来。如今在这巡盐御史林家做馆了。你看,这等子弟,必不能守祖父之根基,从师长之规谏的。只可惜他家几个姊妹都是少有的。”

子兴道:“便是贾府中,现有的三个也不错。政老爹的长女,名元春,现因贤孝才德,选入宫作女史去了。二小姐乃赦老爹之妾所出,名迎春,三小姐乃政老爹之庶出,名探春,四小姐乃宁府珍爷之胞妹,名唤惜春。因史老夫人极爱孙女,都跟在祖母这边一处读书,听得个个不错。雨村道:“更妙在甄家的风俗,女儿之名,亦皆从男子之名命字,不似别家另外用这些‘春’‘红’‘香’‘玉’等艳字的。何得贾府亦乐此俗套?"子兴道:“不然。只因现今大小姐是正月初一日所生,故名元春,余者方从了‘春’字。上一辈的,却也是从兄弟而来的。现有对证:目今你贵东家林公之夫人,即荣府中赦,政二公之胞妹,在家时名唤贾敏。不信时,你回去细访可知。”雨村拍案笑道:“怪道这女学生读至凡书中有‘敏’字,皆念作‘密’字,每每如是,写字遇着‘敏’字,又减一二笔,我心中就有些疑惑。今听你说的,是为此无疑矣。怪道我这女学生言语举止另是一样,不与近日女子相同,度其母必不凡,方得其女,今知为荣府之孙,又不足罕矣,可伤上月竟亡故了。”子兴叹道:“老姊妹四个,这一个是极小的,又没了。长一辈的姊妹,一个也没了。只看这小一辈的,将来之东床如何呢。”

雨村道:“正是。方才说这政公,已有衔玉之儿,又有长子所遗一个弱孙。这赦老竟无一个不成?"子兴道:“政公既有玉儿之后,其妾又生了一个,倒不知其好歹。只眼前现有二子一孙,却不知将来如何。若问那赦公,也有二子,长名贾琏,今已二十来往了,亲上作亲,娶的就是政老爹夫人王氏之内侄女,今已娶了二年。这位琏爷身上现捐的是个同知,也是不肯读书,于世路上好机变,言谈去的,所以如今只在乃叔政老爷家住着,帮着料理些家务。谁知自娶了他令夫人之后,倒上下无一人不称颂他夫人的,琏爷倒退了一射之地:说模样又极标致,言谈又爽利,心机又极深细,竟是个男人万不及一的。”

雨村听了,笑道:“可知我前言不谬。你我方才所说的这几个人,都只怕是那正邪两赋而来一路之人,未可知也。”子兴道:“邪也罢,正也罢,只顾算别人家的帐,你也吃一杯酒才好。”雨村道:“正是,只顾说话,竟多吃了几杯。”子兴笑道:“说着别人家的闲话,正好下酒,即多吃几杯何妨。”雨村向窗外看道:“天也晚了,仔细关了城。我们慢慢的进城再谈,未为不可。”于是,二人起身,算还酒帐。方欲走时,又听得后面有人叫道:“雨村兄,恭喜了!特来报个喜信的。”雨村忙回头看时-

The spirit of Mrs. Chia Shih-yin departs from the town of Yang Chou. Leng Tzu-hsing dilates upon the Jung Kuo Mansion.

To continue. Feng Su, upon hearing the shouts of the public messengers, came out in a flurry and forcing a smile, he asked them to explain (their errand); but all these people did was to continue bawling out: "Be quick, and ask Mr. Chen to come out."

"My surname is Feng," said Feng Su, as he promptly forced himself to smile; "It is'nt Chen at all: I had once a son-in-law whose surname was Chen, but he has left home, it is now already a year or two back. Is it perchance about him that you are inquiring?"

To which the public servants remarked: "We know nothing about Chen or Chia (true or false); but as he is your son-in-law, we'll take you at once along with us to make verbal answer to our master and have done with it."

And forthwith the whole bevy of public servants hustled Feng Su on, as they went on their way back; while every one in the Feng family was seized with consternation, and could not imagine what it was all about.

It was no earlier than the second watch, when Feng Su returned home; and they, one and all, pressed him with questions as to what had happened.

"The fact is," he explained, "the newly-appointed Magistrate, whose surname is Chia, whose name is Huo and who is a native of Hu-chow, has been on intimate terms, in years gone by, with our son-in-law; that at the sight of the girl Chiao Hsing, standing at the door, in the act of buying thread, he concluded that he must have shifted his quarters over here, and hence it was that his messengers came to fetch him. I gave him a clear account of the various circumstances (of his misfortunes), and the Magistrate was for a time much distressed and expressed his regret. He then went on to make inquiries about my grand-daughter, and I explained that she had been lost, while looking at the illuminations. 'No matter,' put in the Magistrate, 'I will by and by order my men to make search, and I feel certain that they will find her and bring her back.' Then ensued a short conversation, after which I was about to go, when he presented me with the sum of two taels."

The mistress of the Chen family (Mrs. Chen Shih-yin) could not but feel very much affected by what she heard, and the whole evening she uttered not a word.

The next day, at an early hour, Yue-ts'un sent some of his men to bring over to Chen's wife presents, consisting of two packets of silver, and four pieces of brocaded silk, as a token of gratitude, and to Feng Su also a confidential letter, requesting him to ask of Mrs. Chen her maid Chiao Hsing to become his second wife.

Feng Su was so intensely delighted that his eyebrows expanded, his eyes smiled, and he felt eager to toady to the Magistrate (by presenting the girl to him). He hastened to employ all his persuasive powers with his daughter (to further his purpose), and on the same evening he forthwith escorted Chiao Hsing in a small chair to the Yamen.

The joy experienced by Yue-ts'un need not be dilated upon. He also presented Feng Su with a packet containing one hundred ounces of gold; and sent numerous valuable presents to Mrs. Chen, enjoining her "to live cheerfully in the anticipation of finding out the whereabouts of her daughter."

It must be explained, however, that the maid Chi'ao Hsing was the very person, who, a few years ago, had looked round at Yue-ts'un and who, by one simple, unpremeditated glance, evolved, in fact, this extraordinary destiny which was indeed an event beyond conception.

Who would ever have foreseen that fate and fortune would both have so favoured her that she should, contrary to all anticipation, give birth to a son, after living with Yue-ts'un barely a year, that in addition to this, after the lapse of another half year, Yue-ts'un's wife should have contracted a sudden illness and departed this life, and that Yue-ts'un should have at once raised her to the rank of first wife. Her destiny is adequately expressed by the lines:

Through but one single, casual look Soon an exalted place she took.

The fact is that after Yue-ts'un had been presented with the money by Shih-yin, he promptly started on the 16th day for the capital, and at the triennial great tripos, his wishes were gratified to the full. Having successfully carried off his degree of graduate of the third rank, his name was put by selection on the list for provincial appointments. By this time, he had been raised to the rank of Magistrate in this district; but, in spite of the excellence and sufficiency of his accomplishments and abilities, he could not escape being ambitious and overbearing. He failed besides, confident as he was in his own merits, in respect toward his superiors, with the result that these officials looked upon him scornfully with the corner of the eye.

A year had hardly elapsed, when he was readily denounced in a memorial to the Throne by the High Provincial authorities, who represented that he was of a haughty disposition, that he had taken upon himself to introduce innovations in the rites and ceremonies, that overtly, while he endeavoured to enjoy the reputation of probity and uprightness, he, secretly, combined the nature of the tiger and wolf; with the consequence that he had been the cause of much trouble in the district, and that he had made life intolerable for the people.

The Dragon countenance of the Emperor was considerably incensed. His Majesty lost no time in issuing commands, in reply to the Memorial, that he should be deprived of his official status.

On the arrival of the despatch from the Board, great was the joy felt by every officer, without exception, of the prefecture in which he had held office. Yue-ts'un, though at heart intensely mortified and incensed, betrayed not the least outward symptom of annoyance, but still preserved, as of old, a smiling and cheerful countenance.

He handed over charge of all official business and removed the savings which he had accumulated during the several years he had been in office, his family and all his chattels to his original home; where, after having put everything in proper order, he himself travelled (carried the winds and sleeved the moon) far and wide, visiting every relic of note in the whole Empire.

As luck would have it, on a certain day while making a second journey through the Wei Yang district, he heard the news that the Salt Commissioner appointed this year was Lin Ju-hai. This Lin Ju-hai's family name was Lin, his name Hai and his style Ju-hai. He had obtained the third place in the previous triennial examination, and had, by this time, already risen to the rank of Director of the Court of Censors. He was a native of Ku Su. He had been recently named by Imperial appointment a Censor attached to the Salt Inspectorate, and had arrived at his post only a short while back.

In fact, the ancestors of Lin Ju-hai had, from years back, successively inherited the title of Marquis, which rank, by its present descent to Ju-hai, had already been enjoyed by five generations. When first conferred, the hereditary right to the title had been limited to three generations; but of late years, by an act of magnanimous favour and generous beneficence, extraordinary bounty had been superadded; and on the arrival of the succession to the father of Ju-hai, the right had been extended to another degree. It had now descended to Ju-hai, who had, besides this title of nobility, begun his career as a successful graduate. But though his family had been through uninterrupted ages the recipient of imperial bounties, his kindred had all been anyhow men of culture.

The only misfortune had been that the several branches of the Lin family had not been prolific, so that the numbers of its members continued limited; and though there existed several households, they were all however to Ju-hai no closer relatives than first cousins. Neither were there any connections of the same lineage, or of the same parentage.

Ju-hai was at this date past forty; and had only had a son, who had died the previous year, in the third year of his age. Though he had several handmaids, he had not had the good fortune of having another son; but this was too a matter that could not be remedied.

By his wife, nee Chia, he had a daughter, to whom the infant name of Tai Yue was given. She was, at this time, in her fifth year. Upon her the parents doated as much as if she were a brilliant pearl in the palm of their hand. Seeing that she was endowed with natural gifts of intelligence and good looks, they also felt solicitous to bestow upon her a certain knowledge of books, with no other purpose than that of satisfying, by this illusory way, their wishes of having a son to nurture and of dispelling the anguish felt by them, on account of the desolation and void in their family circle (round their knees).

But to proceed. Yue-ts'un, while sojourning at an inn, was unexpectedly laid up with a violent chill. Finding on his recovery, that his funds were not sufficient to pay his expenses, he was thinking of looking out for some house where he could find a resting place when he suddenly came across two friends acquainted with the new Salt Commissioner. Knowing that this official was desirous to find a tutor to instruct his daughter, they lost no time in recommending Yue-ts'un, who moved into the Yamen.

His female pupil was youthful in years and delicate in physique, so that her lessons were irregular. Besides herself, there were only two waiting girls, who remained in attendance during the hours of study, so that Yue-ts'un was spared considerable trouble and had a suitable opportunity to attend to the improvement of his health.

In a twinkle, another year and more slipped by, and when least expected, the mother of his ward, nee Chia, was carried away after a short illness. His pupil (during her mother's sickness) was dutiful in her attendance, and prepared the medicines for her use. (And after her death,) she went into the deepest mourning prescribed by the rites, and gave way to such excess of grief that, naturally delicate as she was, her old complaint, on this account, broke out anew.

Being unable for a considerable time to prosecute her studies, Yue-ts'un lived at leisure and had no duties to attend to. Whenever therefore the wind was genial and the sun mild, he was wont to stroll at random, after he had done with his meals.

On this particular day, he, by some accident, extended his walk beyond the suburbs, and desirous to contemplate the nature of the rustic scenery, he, with listless step, came up to a spot encircled by hills and streaming pools, by luxuriant clumps of trees and thick groves of bamboos. Nestling in the dense foliage stood a temple. The doors and courts were in ruins. The walls, inner and outer, in disrepair. An inscription on a tablet testified that this was the temple of Spiritual Perception. On the sides of the door was also a pair of old and dilapidated scrolls with the following enigmatical verses.

Behind ample there is, yet to retract the hand, the mind heeds not, until. Before the mortal vision lies no path, when comes to turn the will.

"These two sentences," Yue-ts'un pondered after perusal, "although simple in language, are profound in signification. I have previous to this visited many a spacious temple, located on hills of note, but never have I beheld an inscription referring to anything of the kind. The meaning contained in these words must, I feel certain, owe their origin to the experiences of some person or other; but there's no saying. But why should I not go in and inquire for myself?"

Upon walking in, he at a glance caught sight of no one else, but of a very aged bonze, of unkempt appearance, cooking his rice. When Yue-ts'un perceived that he paid no notice, he went up to him and asked him one or two questions, but as the old priest was dull of hearing and a dotard, and as he had lost his teeth, and his tongue was blunt, he made most irrelevant replies.

Yue-ts'un lost all patience with him, and withdrew again from the compound with the intention of going as far as the village public house to have a drink or two, so as to enhance the enjoyment of the rustic scenery. With easy stride, he accordingly walked up to the place. Scarcely had he passed the threshold of the public house, when he perceived some one or other among the visitors who had been sitting sipping their wine on the divan, jump up and come up to greet him, with a face beaming with laughter.

"What a strange meeting! What a strange meeting!" he exclaimed aloud.

Yue-ts'un speedily looked at him, (and remembered) that this person had, in past days, carried on business in a curio establishment in the capital, and that his surname was Leng and his style Tzu-hsing.

A mutual friendship had existed between them during their sojourn, in days of yore, in the capital; and as Yue-ts'un had entertained the highest opinion of Leng Tzu-hsing, as being a man of action and of great abilities, while this Leng Tzu-hsing, on the other hand, borrowed of the reputation of refinement enjoyed by Yue-ts'un, the two had consequently all along lived in perfect harmony and companionship.

"When did you get here?" Yue-ts'un eagerly inquired also smilingly. "I wasn't in the least aware of your arrival. This unexpected meeting is positively a strange piece of good fortune."

"I went home," Tzu-hsing replied, "about the close of last year, but now as I am again bound to the capital, I passed through here on my way to look up a friend of mine and talk some matters over. He had the kindness to press me to stay with him for a couple of days longer, and as I after all have no urgent business to attend to, I am tarrying a few days, but purpose starting about the middle of the moon. My friend is busy to-day, so I roamed listlessly as far as here, never dreaming of such a fortunate meeting."

While speaking, he made Yue-ts'un sit down at the same table, and ordered a fresh supply of wine and eatables; and as the two friends chatted of one thing and another, they slowly sipped their wine.

The conversation ran on what had occurred after the separation, and Yue-ts'un inquired, "Is there any news of any kind in the capital?"

"There's nothing new whatever," answered Tzu-hsing. "There is one thing however: in the family of one of your worthy kinsmen, of the same name as yourself, a trifling, but yet remarkable, occurrence has taken place."

"None of my kindred reside in the capital," rejoined Yue-ts'un with a smile. "To what can you be alluding?"

"How can it be that you people who have the same surname do not belong to one clan?" remarked Tzu-hsing, sarcastically.

"In whose family?" inquired Yue-ts'un.

"The Chia family," replied Tzu-hsing smiling, "whose quarters are in the Jung Kuo Mansion, does not after all reflect discredit upon the lintel of your door, my venerable friend."

"What!" exclaimed Yue-ts'un, "did this affair take place in that family? Were we to begin reckoning, we would find the members of my clan to be anything but limited in number. Since the time of our ancestor Chia Fu, who lived while the Eastern Han dynasty occupied the Throne, the branches of our family have been numerous and flourishing; they are now to be found in every single province, and who could, with any accuracy, ascertain their whereabouts? As regards the Jung-kuo branch in particular, their names are in fact inscribed on the same register as our own, but rich and exalted as they are, we have never presumed to claim them as our relatives, so that we have become more and more estranged."

"Don't make any such assertions," Tzu-hsing remarked with a sigh, "the present two mansions of Jung and Ning have both alike also suffered reverses, and they cannot come up to their state of days of yore."

"Up to this day, these two households of Ning and of Jung," Yue-ts'un suggested, "still maintain a very large retinue of people, and how can it be that they have met with reverses?"

"To explain this would be indeed a long story," said Leng Tzu-hsing. "Last year," continued Yue-ts'un, "I arrived at Chin Ling, as I entertained a wish to visit the remains of interest of the six dynasties, and as I on that day entered the walled town of Shih T'ou, I passed by the entrance of that old residence. On the east side of the street, stood the Ning Kuo mansion; on the west the Jung Kuo mansion; and these two, adjoining each other as they do, cover in fact well-nigh half of the whole length of the street. Outside the front gate everything was, it is true, lonely and deserted; but at a glance into the interior over the enclosing wall, I perceived that the halls, pavilions, two-storied structures and porches presented still a majestic and lofty appearance. Even the flower garden, which extends over the whole area of the back grounds, with its trees and rockeries, also possessed to that day an air of luxuriance and freshness, which betrayed no signs of a ruined or decrepid establishment."

"You have had the good fortune of starting in life as a graduate," explained Tzu-tsing as he smiled, "and yet are not aware of the saying uttered by some one of old: that a centipede even when dead does not lie stiff. (These families) may, according to your version, not be up to the prosperity of former years, but, compared with the family of an ordinary official, their condition anyhow presents a difference. Of late the number of the inmates has, day by day, been on the increase; their affairs have become daily more numerous; of masters and servants, high and low, who live in ease and respectability very many there are; but of those who exercise any forethought, or make any provision, there is not even one. In their daily wants, their extravagances, and their expenditure, they are also unable to adapt themselves to circumstances and practise economy; (so that though) the present external framework may not have suffered any considerable collapse, their purses have anyhow begun to feel an exhausting process! But this is a mere trifle. There is another more serious matter. Would any one ever believe that in such families of official status, in a clan of education and culture, the sons and grandsons of the present age would after all be each (succeeding) generation below the standard of the former?"

Yue-ts'un, having listened to these remarks, observed: "How ever can it be possible that families of such education and refinement can observe any system of training and nurture which is not excellent? Concerning the other branches, I am not in a position to say anything; but restricting myself to the two mansions of Jung and Ning, they are those in which, above all others, the education of their children is methodical."

"I was just now alluding to none other than these two establishments," Tzu-hsing observed with a sigh; "but let me tell you all. In days of yore, the duke of Ning Kuo and the duke of Jung Kuo were two uterine brothers. The Ning duke was the elder; he had four sons. After the death of the duke of Ning Kuo, his eldest son, Chia Tai-hua, came into the title. He also had two sons; but the eldest, whose name was Hu, died at the age of eight or nine; and the only survivor, the second son, Chia Ching, inherited the title. His whole mind is at this time set upon Taoist doctrines; his sole delight is to burn the pill and refine the dual powers; while every other thought finds no place in his mind. Happily, he had, at an early age, left a son, Chia Chen, behind in the lay world, and his father, engrossed as his whole heart was with the idea of attaining spiritual life, ceded the succession of the official title to him. His parent is, besides, not willing to return to the original family seat, but lives outside the walls of the capital, foolishly hobnobbing with all the Taoist priests. This Mr. Chen had also a son, Chia Jung, who is, at this period, just in his sixteenth year. Mr. Ching gives at present no attention to anything at all, so that Mr. Chen naturally devotes no time to his studies, but being bent upon nought else but incessant high pleasure, he has subversed the order of things in the Ning Kuo mansion, and yet no one can summon the courage to come and hold him in check. But I'll now tell you about the Jung mansion for your edification. The strange occurrence, to which I alluded just now, came about in this manner. After the demise of the Jung duke, the eldest son, Chia Tai-shan, inherited the rank. He took to himself as wife, the daughter of Marquis Shih, a noble family of Chin Ling, by whom he had two sons; the elder being Chia She, the younger Chia Cheng. This Tai Shan is now dead long ago; but his wife is still alive, and the elder son, Chia She, succeeded to the degree. He is a man of amiable and genial disposition, but he likewise gives no thought to the direction of any domestic concern. The second son Chia Cheng displayed, from his early childhood, a great liking for books, and grew up to be correct and upright in character. His grandfather doated upon him, and would have had him start in life through the arena of public examinations, but, when least expected, Tai-shan, being on the point of death, bequeathed a petition, which was laid before the Emperor. His Majesty, out of regard for his former minister, issued immediate commands that the elder son should inherit the estate, and further inquired how many sons there were besides him, all of whom he at once expressed a wish to be introduced in his imperial presence. His Majesty, moreover, displayed exceptional favour, and conferred upon Mr. Cheng the brevet rank of second class Assistant Secretary (of a Board), and commanded him to enter the Board to acquire the necessary experience. He has already now been promoted to the office of second class Secretary. This Mr. Cheng's wife, nee Wang, first gave birth to a son called Chia Chu, who became a Licentiate in his fourteenth year. At barely twenty, he married, but fell ill and died soon after the birth of a son. Her (Mrs. Cheng's) second child was a daughter, who came into the world, by a strange coincidence, on the first day of the year. She had an unexpected (pleasure) in the birth, the succeeding year, of another son, who, still more remarkable to say, had, at the time of his birth, a piece of variegated and crystal-like brilliant jade in his mouth, on which were yet visible the outlines of several characters. Now, tell me, was not this a novel and strange occurrence? eh?"

"Strange indeed!" exclaimed Yue-ts'un with a smile; "but I presume the coming experiences of this being will not be mean."

Tzu-hsing gave a faint smile. "One and all," he remarked, "entertain the same idea. Hence it is that his mother doats upon him like upon a precious jewel. On the day of his first birthday, Mr. Cheng readily entertained a wish to put the bent of his inclinations to the test, and placed before the child all kinds of things, without number, for him to grasp from. Contrary to every expectation, he scorned every other object, and, stretching forth his hand, he simply took hold of rouge, powder and a few hair-pins, with which he began to play. Mr. Cheng experienced at once displeasure, as he maintained that this youth would, by and bye, grow up into a sybarite, devoted to wine and women, and for this reason it is, that he soon began to feel not much attachment for him. But his grandmother is the one who, in spite of everything, prizes him like the breath of her own life. The very mention of what happened is even strange! He is now grown up to be seven or eight years old, and, although exceptionally wilful, in intelligence and precocity, however, not one in a hundred could come up to him! And as for the utterances of this child, they are no less remarkable. The bones and flesh of woman, he argues, are made of water, while those of man of mud. 'Women to my eyes are pure and pleasing,' he says, 'while at the sight of man, I readily feel how corrupt, foul and repelling they are!' Now tell me, are not these words ridiculous? There can be no doubt whatever that he will by and bye turn out to be a licentious roue."

Yue-ts'un, whose countenance suddenly assumed a stern air, promptly interrupted the conversation. "It doesn't quite follow," he suggested. "You people don't, I regret to say, understand the destiny of this child. The fact is that even the old Hanlin scholar Mr. Cheng was erroneously looked upon as a loose rake and dissolute debauchee! But unless a person, through much study of books and knowledge of letters, so increases (in lore) as to attain the talent of discerning the nature of things, and the vigour of mind to fathom the Taoist reason as well as to comprehend the first principle, he is not in a position to form any judgment."

Tzu-hsing upon perceiving the weighty import of what he propounded, "Please explain," he asked hastily, "the drift (of your argument)." To which Yue-ts'un responded: "Of the human beings created by the operation of heaven and earth, if we exclude those who are gifted with extreme benevolence and extreme viciousness, the rest, for the most part, present no striking diversity. If they be extremely benevolent, they fall in, at the time of their birth, with an era of propitious fortune; while those extremely vicious correspond, at the time of their existence, with an era of calamity. When those who coexist with propitious fortune come into life, the world is in order; when those who coexist with unpropitious fortune come into life, the world is in danger. Yao, Shun, Yue, Ch'eng T'ang, Wen Wang, Wu Wang, Chou Kung, Chao Kung, Confucius, Mencius, T'ung Hu, Han Hsin, Chou Tzu, Ch'eng Tzu, Chu Tzu and Chang Tzu were ordained to see light in an auspicious era. Whereas Ch'i Yu, Kung Kung, Chieh Wang, Chou Wang, Shih Huang, Wang Mang, Tsao Ts'ao, Wen Wen, An Hu-shan, Ch'in Kuei and others were one and all destined to come into the world during a calamitous age. Those endowed with extreme benevolence set the world in order; those possessed of extreme maliciousness turn the world into disorder. Purity, intelligence, spirituality and subtlety constitute the vital spirit of right which pervades heaven and earth, and the persons gifted with benevolence are its natural fruit. Malignity and perversity constitute the spirit of evil, which permeates heaven and earth, and malicious persons are affected by its influence. The days of perpetual happiness and eminent good fortune, and the era of perfect peace and tranquility, which now prevail, are the offspring of the pure, intelligent, divine and subtle spirit which ascends above, to the very Emperor, and below reaches the rustic and uncultured classes. Every one is without exception under its influence. The superfluity of the subtle spirit expands far and wide, and finding nowhere to betake itself to, becomes, in due course, transformed into dew, or gentle breeze; and, by a process of diffusion, it pervades the whole world.

"The spirit of malignity and perversity, unable to expand under the brilliant sky and transmuting sun, eventually coagulates, pervades and stops up the deep gutters and extensive caverns; and when of a sudden the wind agitates it or it be impelled by the clouds, and any slight disposition, on its part, supervenes to set itself in motion, or to break its bounds, and so little as even the minutest fraction does unexpectedly find an outlet, and happens to come across any spirit of perception and subtlety which may be at the time passing by, the spirit of right does not yield to the spirit of evil, and the spirit of evil is again envious of the spirit of right, so that the two do not harmonize. Just like wind, water, thunder and lightning, which, when they meet in the bowels of the earth, must necessarily, as they are both to dissolve and are likewise unable to yield, clash and explode to the end that they may at length exhaust themselves. Hence it is that these spirits have also forcibly to diffuse themselves into the human race to find an outlet, so that they may then completely disperse, with the result that men and women are suddenly imbued with these spirits and spring into existence. At best, (these human beings) cannot be generated into philanthropists or perfect men; at worst, they cannot also embody extreme perversity or extreme wickedness. Yet placed among one million beings, the spirit of intelligence, refinement, perception and subtlety will be above these one million beings; while, on the other hand, the perverse, depraved and inhuman embodiment will likewise be below the million of men. Born in a noble and wealthy family, these men will be a salacious, lustful lot; born of literary, virtuous or poor parentage, they will turn out retired scholars or men of mark; though they may by some accident be born in a destitute and poverty-stricken home, they cannot possibly, in fact, ever sink so low as to become runners or menials, or contentedly brook to be of the common herd or to be driven and curbed like a horse in harness. They will become, for a certainty, either actors of note or courtesans of notoriety; as instanced in former years by Hsue Yu, T'ao Ch'ien, Yuan Chi, Chi Kang, Liu Ling, the two families of Wang and Hsieh, Ku Hu-t'ou, Ch'en Hou-chu, T'ang Ming-huang, Sung Hui-tsung, Liu T'ing-chih, Wen Fei-ching, Mei Nan-kung, Shih Man-ch'ing, Lui C'hih-ch'ing and Chin Shao-yu, and exemplified now-a-days by Ni Yuen-lin, T'ang Po-hu, Chu Chih-shan, and also by Li Kuei-men, Huang P'an-cho, Ching Hsin-mo, Cho Wen-chuen; and the women Hung Fu, Hsieh T'ao, Ch'ue Ying, Ch'ao Yuen and others; all of whom were and are of the same stamp, though placed in different scenes of action."

"From what you say," observed Tzu-hsing, "success makes (a man) a duke or a marquis; ruin, a thief!"

"Quite so; that's just my idea!" replied Yue-ts'un; "I've not as yet let you know that after my degradation from office, I spent the last couple of years in travelling for pleasure all over each province, and that I also myself came across two extraordinary youths. This is why, when a short while back you alluded to this Pao-yue, I at once conjectured, with a good deal of certainty, that he must be a human being of the same stamp. There's no need for me to speak of any farther than the walled city of Chin Ling. This Mr. Chen was, by imperial appointment, named Principal of the Government Public College of the Chin Ling province. Do you perhaps know him?"

"Who doesn't know him?" remarked Tzu-hsing. "This Chen family is an old connection of the Chia family. These two families were on terms of great intimacy, and I myself likewise enjoyed the pleasure of their friendship for many a day."

"Last year, when at Chin Ling," Yue-ts'un continued with a smile, "some one recommended me as resident tutor to the school in the Chen mansion; and when I moved into it I saw for myself the state of things. Who would ever think that that household was grand and luxurious to such a degree! But they are an affluent family, and withal full of propriety, so that a school like this was of course not one easy to obtain. The pupil, however, was, it is true, a young tyro, but far more troublesome to teach than a candidate for the examination of graduate of the second degree. Were I to enter into details, you would indeed have a laugh. 'I must needs,' he explained, 'have the company of two girls in my studies to enable me to read at all, and to keep likewise my brain clear. Otherwise, if left to myself, my head gets all in a muddle.' Time after time, he further expounded to his young attendants, how extremely honourable and extremely pure were the two words representing woman, that they are more valuable and precious than the auspicious animal, the felicitous bird, rare flowers and uncommon plants. 'You may not' (he was wont to say), 'on any account heedlessly utter them, you set of foul mouths and filthy tongues! these two words are of the utmost import! Whenever you have occasion to allude to them, you must, before you can do so with impunity, take pure water and scented tea and rinse your mouths. In the event of any slip of the tongue, I shall at once have your teeth extracted, and your eyes gouged out.' His obstinacy and waywardness are, in every respect, out of the common. After he was allowed to leave school, and to return home, he became, at the sight of the young ladies, so tractable, gentle, sharp, and polite, transformed, in fact, like one of them. And though, for this reason, his father has punished him on more than one occasion, by giving him a sound thrashing, such as brought him to the verge of death, he cannot however change. Whenever he was being beaten, and could no more endure the pain, he was wont to promptly break forth in promiscuous loud shouts, 'Girls! girls!' The young ladies, who heard him from the inner chambers, subsequently made fun of him. 'Why,' they said, 'when you are being thrashed, and you are in pain, your only thought is to bawl out girls! Is it perchance that you expect us young ladies to go and intercede for you? How is that you have no sense of shame?' To their taunts he gave a most plausible explanation. 'Once,' he replied, 'when in the agony of pain, I gave vent to shouting girls, in the hope, perchance, I did not then know, of its being able to alleviate the soreness. After I had, with this purpose, given one cry, I really felt the pain considerably better; and now that I have obtained this secret spell, I have recourse, at once, when I am in the height of anguish, to shouts of girls, one shout after another. Now what do you say to this? Isn't this absurd, eh?"

"The grandmother is so infatuated by her extreme tenderness for this youth, that, time after time, she has, on her grandson's account, found fault with the tutor, and called her son to task, with the result that I resigned my post and took my leave. A youth, with a disposition such as his, cannot assuredly either perpetuate intact the estate of his father and grandfather, or follow the injunctions of teacher or advice of friends. The pity is, however, that there are, in that family, several excellent female cousins, the like of all of whom it would be difficult to discover."

"Quite so!" remarked Tzu-hsing; "there are now three young ladies in the Chia family who are simply perfection itself. The eldest is a daughter of Mr. Cheng, Yuan Ch'un by name, who, on account of her excellence, filial piety, talents, and virtue, has been selected as a governess in the palace. The second is the daughter of Mr. She's handmaid, and is called Ying Ch'un; the third is T'an Ch'un, the child of Mr. Cheng's handmaid; while the fourth is the uterine sister of Mr. Chen of the Ning Mansion. Her name is Hsi Ch'un. As dowager lady Shih is so fondly attached to her granddaughters, they come, for the most part, over to their grandmother's place to prosecute their studies together, and each one of these girls is, I hear, without a fault."

"More admirable," observed Yue-ts'un, "is the regime (adhered to) in the Chen family, where the names of the female children have all been selected from the list of male names, and are unlike all those out-of-the-way names, such as Spring Blossom, Scented Gem, and the like flowery terms in vogue in other families. But how is it that the Chia family have likewise fallen into this common practice?"

"Not so!" ventured Tzu-h'sing. "It is simply because the eldest daughter was born on the first of the first moon, that the name of Yuan Ch'un was given to her; while with the rest this character Ch'un (spring) was then followed. The names of the senior generation are, in like manner, adopted from those of their brothers; and there is at present an instance in support of this. The wife of your present worthy master, Mr. Lin, is the uterine sister of Mr. Chia. She and Mr. Chia Cheng, and she went, while at home, under the name of Chia Min. Should you question the truth of what I say, you are at liberty, on your return, to make minute inquiries and you'll be convinced."

Yue-ts'un clapped his hands and said smiling, "It's so, I know! for this female pupil of mine, whose name is Tai-yue, invariably pronounces the character _min_ as _mi_, whenever she comes across it in the course of her reading; while, in writing, when she comes to the character 'min,' she likewise reduces the strokes by one, sometimes by two. Often have I speculated in my mind (as to the cause), but the remarks I've heard you mention, convince me, without doubt, that it is no other reason (than that of reverence to her mother's name). Strange enough, this pupil of mine is unique in her speech and deportment, and in no way like any ordinary young lady. But considering that her mother was no commonplace woman herself, it is natural that she should have given birth to such a child. Besides, knowing, as I do now, that she is the granddaughter of the Jung family, it is no matter of surprise to me that she is what she is. Poor girl, her mother, after all, died in the course of the last month."

Tzu-hsing heaved a sigh. "Of three elderly sisters," he explained, "this one was the youngest, and she too is gone! Of the sisters of the senior generation not one even survives! But now we'll see what the husbands of this younger generation will be like by and bye!"

"Yes," replied Yue-ts'un. "But some while back you mentioned that Mr. Cheng has had a son, born with a piece of jade in his mouth, and that he has besides a tender-aged grandson left by his eldest son; but is it likely that this Mr. She has not, himself, as yet, had any male issue?"

"After Mr. Cheng had this son with the jade," Tzu-hsing added, "his handmaid gave birth to another son, who whether he be good or bad, I don't at all know. At all events, he has by his side two sons and a grandson, but what these will grow up to be by and bye, I cannot tell. As regards Mr. Chia She, he too has had two sons; the second of whom, Chia Lien, is by this time about twenty. He took to wife a relative of his, a niece of Mr. Cheng's wife, a Miss Wang, and has now been married for the last two years. This Mr. Lien has lately obtained by purchase the rank of sub-prefect. He too takes little pleasure in books, but as far as worldly affairs go, he is so versatile and glib of tongue, that he has recently taken up his quarters with his uncle Mr. Cheng, to whom he gives a helping hand in the management of domestic matters. Who would have thought it, however, ever since his marriage with his worthy wife, not a single person, whether high or low, has there been who has not looked up to her with regard: with the result that Mr. Lien himself has, in fact, had to take a back seat (_lit_. withdrew 35 li). In looks, she is also so extremely beautiful, in speech so extremely quick and fluent, in ingenuity so deep and astute, that even a man could, in no way, come up to her mark."

After hearing these remarks Yue-ts'un smiled. "You now perceive," he said, "that my argument is no fallacy, and that the several persons about whom you and I have just been talking are, we may presume, human beings, who, one and all, have been generated by the spirit of right, and the spirit of evil, and come to life by the same royal road; but of course there's no saying."

"Enough," cried Tzu-hsing, "of right and enough of evil; we've been doing nothing but settling other people's accounts; come now, have another glass, and you'll be the better for it!"

"While bent upon talking," Yue-ts'un explained, "I've had more glasses than is good for me."

"Speaking of irrelevant matters about other people," Tzu-hsing rejoined complacently, "is quite the thing to help us swallow our wine; so come now; what harm will happen, if we do have a few glasses more."

Yue-ts'un thereupon looked out of the window.

"The day is also far advanced," he remarked, "and if we don't take care, the gates will be closing; let us leisurely enter the city, and as we go along, there will be nothing to prevent us from continuing our chat."

Forthwith the two friends rose from their seats, settled and paid their wine bill, and were just going, when they unexpectedly heard some one from behind say with a loud voice:

"Accept my congratulations, Brother Yue-ts'un; I've now come, with the express purpose of giving you the welcome news!"

Yue-ts'un lost no time in turning his head round to look at the speaker. But reader, if you wish to learn who the man was, listen to the details given in the following chapter.

请欣赏:

请给我换一个看看! 拜托,快把噪音停掉!我读累了,想听点音乐或者请来支歌曲!

【选集】红楼一春梦 |

|

|