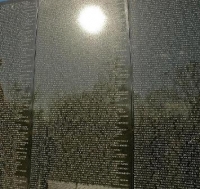

二十六个字母

便把这么多年青的名字

嵌入历史

万人冢中

一个踽踽独行的老妪

终于找到了

她的爱子

此刻她正紧闭双眼

用颤悠悠的手指

沿着他冰冷的额头

找那致命的伤口

and twenty six letters of the alphabet

etch so many young names

onto history

Wandering alone

amid the mass grave

an old woman has at last found

her only child

and with her eyes tightly shut

her trembling fingers now feel

for the mortal wound

on his ice-cold forehead

【赏析】 诗人以平实的语言,以看似简单叙述的方式,铺陈诗歌表达主题。深入而浅出的再现了,在世人共知的越战事件中,许许多多的热血青年,献出自己宝贵青春生命的事实。短短的十二行文字,凝成一枚尖利的镞矢,射向罪恶的战争深处!战争,这邪恶的幽灵,以残酷的手段分裂了人间的至爱亲人,令他们从此迷失在找寻的路途!诗人以一个年迈而独行的老妪为典型来呈现,场景生动且富有强烈的画面感染力。让人读后内心被深深的撕咬撞击着,仿佛一种痛,散发着血腥的气味,越过头顶!

从这篇文字中,我们读到了一个关注和平,关注人间疾苦,有着高尚思想情怀的诗人灵魂内质!他以自己手中的笔,开始了另一场战争,讨伐那些喜欢玩弄野心的战争贩子:他们不顾百姓民生的疾苦,不惜牺牲千千万万的年轻生命,以达到自己霸权私欲目的。多么可恨和可耻!让读者在顷刻间,调动了各种情感元素,跟随诗人语言的脚步,深挖出一个业已被众人忘却一段历史隐痛,引起情感上的共鸣!

让我们以沉痛而崇敬的心来一起默哀,缅怀我们无辜死难的兄弟同胞吧!愿他们的灵魂在天上安息!让我们用愤恨的力量来诅咒,诅咒那些人类灾难性战争的制造者吧!过去的,现在的,未来的!(鹤雨)

<>海伦啊,你的美貌对于我,

就象那古老的尼赛安帆船,

在芬芳的海面上它悠悠荡漾,

载着风尘仆仆疲惫的流浪汉,

驶往故乡的海岸。

你兰紫色的柔发,古典的脸,

久久浮现在波涛汹涌的海面上,

你女神般的风姿,

将我带回往昔希腊的荣耀,

和古罗马的辉煌。

看,神龛金碧,你婷婷玉立,

俨然一尊雕像,

手提玛瑙明灯,

啊,普赛克,

你是来自那神圣的地方!

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

安娜蓓尔·李

那是在许多年、许多年以前,

在海边的一个王国里

住着位姑娘,你可能也知道

她名叫安娜蓓尔·李:

这姑娘的心里没别的思念,

就除了她同我的情意。

那时候我同她都还是孩子,

住在这海边的王国里;

可我同她的爱已不止是爱--

同我的安娜蓓尔·李--

已使天堂中长翅膀的仙子

想把我们的爱夺去。

就因为这道理,很久很久前

在这个海边的王国里,

云头里吹来一阵风,冻了我

美丽的安娜蓓尔·李;

这招来她出身高贵的亲戚,

从我这里把她抢了去,

把她关进石头凿成的墓穴,

在这个海边的王国里。

天上的仙子也没那样快活,

所以把她又把我妒忌--

就因为这道理(大家都知道),

在这个海边的王国里,

夜间的云头里吹来一阵风,

冻死了安娜蓓尔·李。

我们的爱远比其他人强烈--

同年长于我们的相比,

同远为聪明的人相比;

无论是天国中的神人仙子,

还是海底的魔恶鬼厉,

都不能使她美丽的灵魂儿

同我的灵魂儿分离。

因为月亮的光总叫我梦见

美丽的安娜蓓尔·李;

因为升空的星总叫我看见

她那明亮眼睛的美丽;

整夜里我躺在爱人的身边--

这爱人是我生命,是我新娘,

她躺在海边的石穴里,

在澎湃大海边的墓里。

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

最快乐的日子

最快乐的日子,最快乐的时辰

我麻木的心儿所能感知,

最显赫的权势,最辉煌的容幸

我的知觉所能期冀。

我说权势?不错!如我期盼,

可那期盼早已化为乌有!

我青春的梦想也烟消云散——

但就让它们付之东流。

荣耀,我现在与你有何关系?

另一个额头也许会继承

你曾经喷在我身上的毒汁——

安静吧,我的心灵。

最快乐的日子,最快乐的时辰

我的眼睛将看——所一直凝视,

最显赫的权势,最辉煌的荣幸

我的知觉所一直希冀:

但如果那权势和荣耀的希望

现在飞来,带着在那时候

我也感到的痛苦——那极乐时光

我也再不会去享受:

因为希望的翅膀变暗发黑,

而当它飞翔时——掉下一种

原素——其威力足以摧毁

一个以为它美好的灵魂。

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

乌鸦

从前一个阴郁的子夜,我独自沉思,慵懒疲竭,

沉思许多古怪而离奇、早已被人遗忘的传闻——

当我开始打盹,几乎入睡,突然传来一阵轻擂,

仿佛有人在轻轻叩击,轻轻叩击我的房门。

“有人来了,”我轻声嘟喃,“正在叩击我的房门——

唯此而已,别无他般。”

哦,我清楚地记得那是在萧瑟的十二月;

每一团奄奄一息的余烬都形成阴影伏在地板。

我当时真盼望翌日;——因为我已经枉费心机

想用书来消除悲哀——消除因失去丽诺尔的悲叹——

因那被天使叫作丽诺尔的少女,她美丽娇艳——

在这儿却默默无闻,直至永远。

那柔软、暗淡、飒飒飘动的每一块紫色窗布

使我心中充满前所未有的恐怖——我毛骨惊然;

为平息我心儿停跳.我站起身反复叨念

“这是有人想进屋,在叩我的房门——。

更深夜半有人想进屋,在叩我的房门;——

唯此而已,别无他般。”

很快我的心变得坚强;不再犹疑,不再彷徨,

“先生,”我说,“或夫人,我求你多多包涵;

刚才我正睡意昏昏,而你来敲门又那么轻,

你来敲门又那么轻,轻轻叩击我的房门,

我差点以为没听见你”——说着我拉开门扇;——

唯有黑夜,别无他般。

凝视着夜色幽幽,我站在门边惊惧良久,

疑惑中似乎梦见从前没人敢梦见的梦幻;

可那未被打破的寂静,没显示任何迹象。

“丽诺尔?”便是我嗫嚅念叨的唯一字眼,

我念叨“丽诺尔!”,回声把这名字轻轻送还,

唯此而已,别无他般。

我转身回到房中,我的整个心烧灼般疼痛,

很快我又听到叩击声,比刚才听起来明显。

“肯定,”我说,“肯定有什么在我的窗棂;

让我瞧瞧是什么在那里,去把那秘密发现——

让我的心先镇静一会儿,去把那秘密发现;——

那不过是风,别无他般!”

我猛然推开窗户,。心儿扑扑直跳就像打鼓,

一只神圣往昔的健壮乌鸦慢慢走进我房间;

它既没向我致意问候;也没有片刻的停留;

而以绅士淑女的风度,栖在我房门的上面——

栖在我房门上方一尊帕拉斯半身雕像上面——

栖坐在那儿,仅如此这般。

于是这只黑鸟把我悲伤的幻觉哄骗成微笑,

以它那老成持重一本正经温文尔雅的容颜,

“虽然冠毛被剪除,”我说,“但你肯定不是懦夫,

你这幽灵般可怕的古鸦,漂泊来自夜的彼岸——

请告诉我你尊姓大名,在黑沉沉的冥府阴间!”

乌鸦答日“永不复述。”

听见如此直率的回答,我惊叹这丑陋的乌鸦,

虽说它的回答不着边际——与提问几乎无关;

因为我们不得不承认,从来没有活着的世人

曾如此有幸地看见一只鸟栖在他房门的面——

鸟或兽栖在他房间门上方的半身雕像上面,

有这种名字“水不复还。”

但那只独栖于肃穆的半身雕像上的乌鸦只说了

这一句话,仿佛它倾泻灵魂就用那一个字眼。

然后它便一声不吭——也不把它的羽毛拍动——

直到我几乎是哺哺自语“其他朋友早已消散——

明晨它也将离我而去——如同我的希望已消散。”

这时那鸟说“永不复还。”

惊异于那死寂漠漠被如此恰当的回话打破,

“肯定,”我说,“这句话是它唯一的本钱,

从它不幸动主人那儿学未。一连串无情飞灾

曾接踵而至,直到它主人的歌中有了这字眼——

直到他希望的挽歌中有了这个忧伤的字眼

‘永不复还,永不复还。’”

但那只乌鸦仍然把我悲伤的幻觉哄骗成微笑,

我即刻拖了张软椅到门旁雕像下那只鸟跟前;

然后坐在天鹅绒椅垫上,我开始冥思苦想,

浮想连着浮想,猜度这不祥的古鸟何出此言——

这只狰狞丑陋可怕不吉不祥的古鸟何出此言,

为何聒噪‘永不复还。”

我坐着猜想那意见但没对那鸟说片语只言。

此时,它炯炯发光的眼睛已燃烧进我的心坎;

我依然坐在那儿猜度,把我的头靠得很舒服,

舒舒服服地靠在那被灯光凝视的天鹅绒衬垫,

但被灯光爱慕地凝视着的紫色的天鹅绒衬垫,

她将显出,啊,永不复还!

接着我想,空气变得稠密,被无形香炉熏香,

提香炉的撒拉弗的脚步声响在有簇饰的地板。

“可怜的人,”我呼叫,“是上帝派天使为你送药,

这忘忧药能中止你对失去的丽诺尔的思念;

喝吧如吧,忘掉对失去的丽诺尔的思念!”

乌鸦说“永不复还。”

“先知!”我说“凶兆!——仍是先知,不管是鸟还是魔!

是不是魔鬼送你,或是暴风雨抛你来到此岸,

孤独但毫不气馁,在这片妖惑鬼崇的荒原——

在这恐怖萦绕之家——告诉我真话,求你可怜——

基列有香膏吗?——告诉我——告诉我,求你可怜!”

乌鸦说“永不复还。”

“先知!”我说,“凶兆!——仍是先知、不管是鸟是魔!

凭我们头顶的苍天起誓——凭我们都崇拜的上帝起誓——

告诉这充满悲伤的灵魂。它能否在遥远的仙境

拥抱被天使叫作丽诺尔的少女,她纤尘不染——

拥抱被天使叫作丽诺尔的少女,她美丽娇艳。”

乌鸦说“永不复还。”

“让这话做我们的道别之辞,鸟或魔!”我突然叫道——

“回你的暴风雨中去吧,回你黑沉沉的冥府阴间!

别留下黑色羽毛作为你的灵魂谎言的象征!

留给我完整的孤独!——快从我门上的雕像滚蛋!

从我心中带走你的嘴;从我房门带走你的外观!”

乌鸦说“永不复还。”

那乌鸦并没飞去,它仍然栖息,仍然栖息

在房门上方那苍白的帕拉斯半身雕像上面;

而它的眼光与正在做梦的魔鬼眼光一模一样,

照在它身上的灯光把它的阴影投射在地板;

而我的灵魂,会从那团在地板上漂浮的阴暗

被擢升么——永不复还!

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

梦

呵!我的青春是一个长梦该有多好!

愿我的灵魂长梦不醒,一直到

那水恒之光芒送来黎明的曙光;

不错!那长梦中也有忧伤和绝望,

可于他也胜过清醒生活的现实,

他的心,在这个清冷萧瑟的尘世,

从来就是并将是,自从他诞生,

一团强烈激情的纷乱浑沌!

但假若——那个永生延续的梦——

像我有过的许多梦一样落空,

假若它与我儿时的梦一样命运,

那希冀高远的天国仍然太愚蠢!

因为我一直沉迷于夏日的晴天,

因为我一直耽溺于白昼的梦幻,

并把我自己的心,不经意的

一直留在我想象中的地域——

除了我的家,除了我的思索——

我本来还能看见另外的什么?

一次而且只有一次,那癫狂之时

将不会从我的记忆中消失——

是某种力量或符咒把我镇住——

是冰凉的风在夜里把我吹拂,

并把它的形象留在我心中,

或是寒月冷光照耀我的睡梦——

或是那些星星——但无论它是啥,

那梦如寒夜阴风——让它消失吧。

我一直很幸福——虽然只在梦里,

我一直很幸福——我爱梦的旋律——

梦哟!在它们斑斓的色彩之中——

仿佛置身于一场短暂朦胧的斗争,

与现实争斗,斗争为迷眼带来

伊甸乐园的一切美和一切爱——

这爱与美都属于我们自己所有!

美过青春希望所知,在它最快乐的时候。

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

模仿

一股深不可测的潮流,

一股无限自豪的潮流——

一个梦再加一种神秘,

似乎就是我童年的日子;

我是说我童年那个梦想

充满一种关于生命的思想,

它疯狂而清醒地一再闪现,

可我的心灵却视而不见;

唯愿我不曾让它们消失,

从我昏花速成的眼里!

那我将绝不会让世人

享有我心灵的幻影;

我会控制那些思路,

作为镇他灵魂的咒符;

因为灿烂的希望已消失,

欢乐时光终于过去,

我人世的休眠已结束

随着像是死亡的一幕;

我珍惜的思想一道消散

可我对此处之淡然。

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

湖——致——

我命中注定在年少之时

常去这荒芜世界的一隅,

现在我依然爱那个地方——

如此可爱是那湖的凄凉,

凄凉的湖,湖畔黑岩磷峋,

湖边还有苍松高耸入云。

可是当黑暗撒开夜幕

将那湖与世界一同罩住,

当神秘的风在我耳边

悄声诉说着蜜语甜言——

这时——哦这时我会醒悟,

会意识到那孤湖的恐怖。

可那种恐怖并不吓人,

不过是一阵发抖的高兴——

一种感情,即便用满山宝石

也不能诱惑我下出定义——

爱也不能——纵然那爱是你的。

死亡就在那有毒的涟漪里,

在它的深渊,有一块坟地

适合于他,他能从那墓堆

为他孤独的想象带来安慰——

他寂寞的灵魂能够去改变。

把凄凉的湖交成伊甸乐园。

In placing before the public this collection of Edgar Poe's poetical

works, it is requisite to point out in what respects it differs from,

and is superior to, the numerous collections which have preceded it.

Until recently, all editions, whether American or English, of Poe's

poems have been 'verbatim' reprints of the first posthumous collection,

published at New York in 1850.

In 1874 I began drawing attention to the fact that unknown and

unreprinted poetry by Edgar Poe was in existence. Most, if not all, of

the specimens issued in my articles have since been reprinted by

different editors and publishers, but the present is the first occasion

on which all the pieces referred to have been garnered into one sheaf.

Besides the poems thus alluded to, this volume will be found to contain

many additional pieces and extra stanzas, nowhere else published or

included in Poe's works. Such verses have been gathered from printed or

manuscript sources during a research extending over many years.

In addition to the new poetical matter included in this volume,

attention should, also, be solicited on behalf of the notes, which will

be found to contain much matter, interesting both from biographical and

bibliographical points of view.

JOHN H. INGRAM.

CONTENTS.

MEMOIR

POEMS OF LATER LIFE:

Dedication

Preface

The Raven

The Bells

Ulalume

To Helen

Annabel Lee

A Valentine

An Enigma

To my Mother

For Annie

To F----

To Frances S. Osgood

Eldorado

Eulalie

A Dream within a Dream

To Marie Louise (Shew)

To the Same

The City in the Sea

The Sleeper,

Bridal Ballad

Notes

POEMS OF MANHOOD:

Lenore

To one in Paradise

The Coliseum

The Haunted Palace

The Conqueror Worm

Silence

Dreamland

To Zante

Hymn

Notes

SCENES FROM "POLITIAN"

Note

POEMS OF YOUTH:

Introduction (1831)

To Science

Al Aaraaf

Tamerlane

To Helen

The Valley of Unrest

Israfel

To----("I heed not that my earthly lot")

To----("The bowers whereat, in dreams, I see")

To the River----

Song

Spirits of the Dead

A Dream

Romance

Fairyland

The Lake

Evening Star

Imitation

"The Happiest Day,"

Hymn. Translation from the Greek

Dreams

"In Youth I have known one"

A P鎍n

Notes

DOUBTFUL POEMS:

Alone

To Isadore

The Village Street

The Forest Reverie

Notes

PROSE POEMS:

The Island of the Fay

The Power of Words

The Colloquy of Monos and Una

The Conversation of Eiros and Charmion

Shadow--A Parable

Silence--A Fable

ESSAYS:

The Poetic Principle

The Philosophy of Composition

Old English Poetry

MEMOIR OF EDGAR ALLAN POE.

During the last few years every incident in the life of Edgar Poe has

been subjected to microscopic investigation. The result has not been

altogether satisfactory. On the one hand, envy and prejudice have

magnified every blemish of his character into crime, whilst on the

other, blind admiration would depict him as far "too good for human

nature's daily food." Let us endeavor to judge him impartially, granting

that he was as a mortal subject to the ordinary weaknesses of mortality,

but that he was tempted sorely, treated badly, and suffered deeply.

The poet's ancestry and parentage are chiefly interesting as explaining

some of the complexities of his character. His father, David Poe, was of

Anglo-Irish extraction. Educated for the Bar, he elected to abandon it

for the stage. In one of his tours through the chief towns of the United

States he met and married a young actress, Elizabeth Arnold, member of

an English family distinguished for its musical talents. As an actress,

Elizabeth Poe acquired some reputation, but became even better known for

her domestic virtues. In those days the United States afforded little

scope for dramatic energy, so it is not surprising to find that when her

husband died, after a few years of married life, the young widow had a

vain struggle to maintain herself and three little ones, William Henry,

Edgar, and Rosalie. Before her premature death, in December, 1811, the

poet's mother had been reduced to the dire necessity of living on the

charity of her neighbors.

Edgar, the second child of David and Elizabeth Poe, was born at Boston,

in the United States, on the 19th of January, 1809. Upon his mother's

death at Richmond, Virginia, Edgar was adopted by a wealthy Scotch

merchant, John Allan. Mr. Allan, who had married an American lady and

settled in Virginia, was childless. He therefore took naturally to the

brilliant and beautiful little boy, treated him as his son, and made him

take his own surname. Edgar Allan, as he was now styled, after some

elementary tuition in Richmond, was taken to England by his adopted

parents, and, in 1816, placed at the Manor House School,

Stoke-Newington.

Under the Rev. Dr. Bransby, the future poet spent a lustrum of his life

neither unprofitably nor, apparently, ungenially. Dr. Bransby, who is

himself so quaintly portrayed in Poe's tale of 'William Wilson',

described "Edgar Allan," by which name only he knew the lad, as "a quick

and clever boy," who "would have been a very good boy had he not been

spoilt by his parents," meaning, of course, the Allans. They "allowed

him an extravagant amount of pocket-money, which enabled him to get into

all manner of mischief. Still I liked the boy," added the tutor, "but,

poor fellow, his parents spoiled him."

Poe has described some aspects of his school days in his oft cited story

of 'William Wilson'. Probably there is the usual amount of poetic

exaggeration in these reminiscences, but they are almost the only record

we have of that portion of his career and, therefore, apart from their

literary merits, are on that account deeply interesting. The description

of the sleepy old London suburb, as it was in those days, is remarkably

accurate, but the revisions which the story of 'William Wilson' went

through before it reached its present perfect state caused many of the

author's details to deviate widely from their original correctness. His

schoolhouse in the earliest draft was truthfully described as an "old,

irregular, and cottage-built" dwelling, and so it remained until its

destruction a few years ago.

The 'soi-disant' William Wilson, referring to those bygone happy days

spent in the English academy, says,

"The teeming brain of childhood requires no external world of incident

to occupy or amuse it. The morning's awakening, the nightly summons to

bed; the connings, the recitations, the periodical half-holidays and

perambulations, the playground, with its broils, its pastimes, its

intrigues--these, by a mental sorcery long forgotten, were made to

involve a wilderness of sensation, a world of rich incident, a

universe of varied emotion, of excitement the most passionate and

spirit-stirring, _'Oh, le bon temps, que ce si鑓le de fer!'"_

From this world of boyish imagination Poe was called to his adopted

parents' home in the United States. He returned to America in 1821, and

was speedily placed in an academy in Richmond, Virginia, in which city

the Allans continued to reside. Already well grounded in the elementary

processes of education, not without reputation on account of his

European residence, handsome, proud, and regarded as the heir of a

wealthy man, Poe must have been looked up to with no little respect by

his fellow pupils. He speedily made himself a prominent position in the

school, not only by his classical attainments, but by his athletic

feats--accomplishments calculated to render him a leader among lads.

"In the simple school athletics of those days, when a gymnasium had

not been heard of, he was 'facile princeps',"

is the reminiscence of his fellow pupil, Colonel T. L. Preston. Poe he

remembers as

"a swift runner, a wonderful leaper, and, what was more rare, a boxer,

with some slight training.... He would allow the strongest boy in the

school to strike him with full force in the chest. He taught me the

secret, and I imitated him, after my measure. It was to inflate the

lungs to the uttermost, and at the moment of receiving the blow to

exhale the air. It looked surprising, and was, indeed, a little rough;

but with a good breast-bone, and some resolution, it was not difficult

to stand it. For swimming he was noted, being in many of his athletic

proclivities surprisingly like Byron in his youth."

In one of his feats Poe only came off second best.

"A challenge to a foot race," says Colonel Preston, "had been passed

between the two classical schools of the city; we _select_ed Poe as our

champion. The race came off one bright May morning at sunrise, in the

Capitol Square. Historical truth compels me to add that on this

occasion our school was beaten, and we had to pay up our small bets.

Poe ran well, but his competitor was a long-legged, Indian-looking

fellow, who would have outstripped Atalanta without the help of the

golden apples."

"In our Latin exercises in school," continues the colonel, "Poe was

among the first--not first without dispute. We had competitors who

fairly disputed the palm, especially one, Nat Howard, afterwards known

as one of the ripest scholars in Virginia, and distinguished also as a

profound lawyer. If Howard was less brilliant than Poe, he was far

more studious; for even then the germs of waywardness were developing

in the nascent poet, and even then no inconsiderable portion of his

time was given to versifying. But if I put Howard as a Latinist on a

level with Poe, I do him full justice."

"Poe," says the colonel, "was very fond of the Odes of Horace, and

repeated them so often in my hearing that I learned by sound the words

of many before I understood their meaning. In the lilting rhythm of

the Sapphics and Iambics, his ear, as yet untutored in more

complicated harmonies, took special delight. Two odes, in particular,

have been humming in my ear all my life since, set to the tune of his

recitation:

_'Jam satis terris nivis atque dirce

Grandinis misit Pater, et rubente,'_

And

_'Non ebur neque aureum

Mea renidet in dono lacu ar,_' etc.

"I remember that Poe was also a very fine French scholar. Yet, with

all his superiorities, he was not the master spirit nor even the

favorite of the school. I assign, from my recollection, this place to

Howard. Poe, as I recall my impressions now, was self-willed,

capricious, inclined to be imperious, and, though of generous

impulses, not steadily kind, nor even amiable; and so what he would

exact was refused to him. I add another thing which had its influence,

I am sure. At the time of which I speak, Richmond was one of the most

aristocratic cities on this side of the Atlantic.... A school is, of

its nature, democratic; but still boys will unconsciously bear about

the odor of their fathers' notions, good or bad. Of Edgar Poe," who

had then resumed his parental cognomen, "it was known that his parents

had been players, and that he was dependent upon the bounty that is

bestowed upon an adopted son. All this had the effect of making the

boys decline his leadership; and, on looking back on it since, I fancy

it gave him a fierceness he would otherwise not have had."

This last paragraph of Colonel Preston's recollections cast a suggestive

light upon the causes which rendered unhappy the lad's early life and

tended to blight his prospective hopes. Although mixing with members of

the best families of the province, and naturally endowed with hereditary

and native pride,--fostered by the indulgence of wealth and the

consciousness of intellectual superiority,--Edgar Poe was made to feel

that his parentage was obscure, and that he himself was dependent upon

the charity and caprice of an alien by blood. For many lads these things

would have had but little meaning, but to one of Poe's proud temperament

it must have been a source of constant torment, and all allusions to it

gall and wormwood. And Mr. Allan was not the man to wean Poe from such

festering fancies: as a rule he was proud of the handsome and talented

boy, and indulged him in all that wealth could purchase, but at other

times he treated him with contumely, and made him feel the bitterness of

his position.

Still Poe did maintain his leading position among the scholars at that

Virginian academy, and several still living have favored us with

reminiscences of him. His feats in swimming to which Colonel Preston has

alluded, are quite a feature of his youthful career. Colonel Mayo

records one daring performance in natation which is thoroughly

characteristic of the lad. One day in mid-winter, when standing on the

banks of the James River, Poe dared his comrade into jumping in, in

order to swim to a certain point with him. After floundering about in

the nearly frozen stream for some time, they reached the piles upon

which Mayo's Bridge was then supported, and there attempted to rest and

try to gain the shore by climbing up the log abutment to the bridge.

Upon reaching the bridge, however, they were dismayed to find that its

plank flooring overlapped the abutment by several feet, and that it was

impossible to ascend it. Nothing remained for them but to let go their

slippery hold and swim back to the shore. Poe reached the bank in an

exhausted and benumbed condition, whilst Mayo was rescued by a boat just

as he was succumbing. On getting ashore Poe was seized with a violent

attack of vomiting, and both lads were ill for several weeks.

Alluding to another quite famous swimming feat of his own, the poet

remarked, "Any 'swimmer in the falls' in my days would have swum the

Hellespont, and thought nothing of the matter. I swam from Ludlam's

Wharf to Warwick (six miles), in a hot June sun, against one of the

strongest tides ever known in the river. It would have been a feat

comparatively easy to swim twenty miles in still water. I would not

think much," Poe added in a strain of exaggeration not unusual with him,

"of attempting to swim the British Channel from Dover to Calais."

Colonel Mayo, who had tried to accompany him in this performance, had to

stop on the way, and says that Poe, when he reached the goal, emerged

from the water with neck, face, and back blistered. The facts of this

feat, which was undertaken for a wager, having been questioned, Poe,

ever intolerant of contradiction, obtained and published the affidavits

of several gentlemen who had witnessed it. They also certified that Poe

did not seem at all fatigued, and that he walked back to Richmond

immediately after the performance.

The poet is generally remembered at this part of his career to have been

slight in figure and person, but to have been well made, active, sinewy,

and graceful. Despite the fact that he was thus noted among his

schoolfellows and indulged at home, he does not appear to have been in

sympathy with his surroundings. Already dowered with the "hate of hate,

the scorn of scorn," he appears to have made foes both among those who

envied him and those whom, in the pride of intellectuality, he treated

with pugnacious contempt. Beneath the haughty exterior, however, was a

warm and passionate heart, which only needed circumstance to call forth

an almost fanatical intensity of affection. A well-authenticated

instance of this is thus related by Mrs. Whitman:

"While at the academy in Richmond, he one day accompanied a schoolmate

to his home, where he saw, for the first time, Mrs. Helen Stannard,

the mother of his young friend. This lady, on entering the room, took

his hands and spoke some gentle and gracious words of welcome, which

so penetrated the sensitive heart of the orphan boy as to deprive him

of the power of speech, and for a time almost of consciousness itself.

He returned home in a dream, with but one thought, one hope in life

--to hear again the sweet and gracious words that had made the

desolate world so beautiful to him, and filled his lonely heart with

the oppression of a new joy. This lady afterwards became the confidant

of all his boyish sorrows, and hers was the one redeeming influence

that saved and guided him in the earlier days of his turbulent and

passionate youth."

When Edgar was unhappy at home, which, says his aunt, Mrs. Clemm, "was

very often the case, he went to Mrs. Stannard for sympathy, for

consolation, and for advice." Unfortunately, the sad fortune which so

frequently thwarted his hopes ended this friendship. The lady was

overwhelmed by a terrible calamity, and at the period when her guiding

voice was most requisite, she fell a prey to mental alienation. She

died, and was entombed in a neighboring cemetery, but her poor boyish

admirer could not endure to think of her lying lonely and forsaken in

her vaulted home, so he would leave the house at night and visit her

tomb. When the nights were drear, "when the autumnal rains fell, and the

winds wailed mournfully over the graves, he lingered longest, and came

away most regretfully."

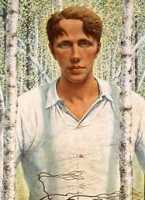

The memory of this lady, of this "one idolatrous and purely ideal love"

of his boyhood, was cherished to the last. The name of Helen frequently

recurs in his youthful verses, "The P鎍n," now first included in his

poetical works, refers to her; and to her he inscribed the classic and

exquisitely beautiful stanzas beginning "Helen, thy beauty is to me."

Another important item to be noted in this epoch of his life is that he

was already a poet. Among his schoolfellows he appears to have acquired

some little reputation as a writer of satirical verses; but of his

poetry, of that which, as he declared, had been with him "not a purpose,

but a passion," he probably preserved the secret, especially as we know

that at his adoptive home poesy was a forbidden thing. As early as 1821

he appears to have essayed various pieces, and some of these were

ultimately included in his first volume. With Poe poetry was a personal

matter--a channel through which the turbulent passions of his heart

found an outlet. With feelings such as were his, it came to pass, as a

matter of course, that the youthful poet fell in love. His first affair

of the heart is, doubtless, reminiscently portrayed in what he says of

his boyish ideal, Byron. This passion, he remarks, "if passion it can

properly be called, was of the most thoroughly romantic, shadowy, and

imaginative character. It was born of the hour, and of the youthful

necessity to love. It had no peculiar regard to the person, or to the

character, or to the reciprocating affection... Any maiden, not

immediately and positively repulsive," he deems would have suited the

occasion of frequent and unrestricted intercourse with such an

imaginative and poetic youth. "The result," he deems, "was not merely

natural, or merely probable; it was as inevitable as destiny itself."

Between the lines may be read the history of his own love. "The Egeria

of _his_ dreams--the Venus Aphrodite that sprang in full and supernal

loveliness from the bright foam upon the storm-tormented ocean of _his_

thoughts," was a little girl, Elmira Royster, who lived with her father

in a house opposite to the Allans in Richmond. The young people met

again and again, and the lady, who has only recently passed away,

recalled Edgar as "a beautiful boy," passionately fond of music,

enthusiastic and impulsive, but with prejudices already strongly

developed. A certain amount of love-making took place between the young

people, and Poe, with his usual passionate energy, ere he left home for

the University had persuaded his fair inamorata to engage herself to

him. Poe left home for the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, in

the beginning of 1825. lie wrote frequently to Miss Royster, but her

father did not approve of the affair, and, so the story runs,

intercepted the correspondence, until it ceased. At seventeen, Elmira

became the bride of a Mr. Shelton, and it was not until some time

afterwards that Poe discovered how it was his passionate appeals had

failed to elicit any response from the object of his youthful affection.

Poe's short university career was in many respects a repetition of his

course at the Richmond Academy. He became noted at Charlottesville both

for his athletic feats and his scholastic successes. He entered as a

student on February 1,1826, and remained till the close of the second

session in December of that year.

"He entered the schools of ancient and modern languages, attending the

lectures on Latin, Greek, French, Spanish, and Italian. I was a member

of the last three classes," says Mr. William Wertenbaker, the recently

deceased librarian, "and can testify that he was tolerably regular in

his attendance, and a successful student, having obtained distinction

at the final examination in Latin and French, and this was at that

time the highest honor a student could obtain. The present regulations

in regard to degrees had not then been adopted. Under existing

regulations, he would have graduated in the two languages above-named,

and have been entitled to diplomas."

These statements of Poe's classmate are confirmed by Dr. Harrison,

chairman of the Faculty, who remarks that the poet was a great favorite

with his fellow-students, and was noted for the remarkable rapidity with

which he prepared his recitations and for their accuracy, his

translations from the modern languages being especially noteworthy.

Several of Poe's classmates at Charlottesville have testified to his

"noble qualities" and other good endowments, but they remember that his

"disposition was rather retiring, and that he had few intimate

associates." Mr. Thomas Boiling, one of his fellow-students who has

favored us with reminiscences of him, says:

"I was 'acquainted', with him, but that is about all. My impression

was, and is, that no one could say that he 'knew' him. He wore a

melancholy face always, and even his smile--for I do not ever remember

to have seen him laugh--seemed to be forced. When he engaged

sometimes with others in athletic exercises, in which, so far as high

or long jumping, I believe he excelled all the rest, Poe, with the

same ever sad face, appeared to participate in what was amusement to

the others more as a task than sport."

Poe had no little talent for drawing, and Mr. John Willis states that

the walls of his college rooms were covered with his crayon sketches,

whilst Mr. Boiling mentions, in connection with the poet's artistic

facility, some interesting incidents. The two young men had purchased

copies of a handsomely-illustrated edition of Byron's poems, and upon

visiting Poe a few days after this purchase, Mr. Bolling found him

engaged in copying one of the engravings with crayon upon his dormitory

ceiling. He continued to amuse himself in this way from time to time

until he had filled all the space in his room with life-size figures

which, it is remembered by those who saw them, were highly ornamental

and well executed.

As Mr. Bolling talked with his associate, Poe would continue to scribble

away with his pencil, as if writing, and when his visitor jestingly

remonstrated with him on his want of politeness, he replied that he had

been all attention, and proved that he had by suitable comment,

assigning as a reason for his apparent want of courtesy that he was

trying 'to divide his mind,' to carry on a conversation and write

sensibly upon a totally different subject at the same time.

Mr. Wertenbaker, in his interesting reminiscences of the poet, says:

"As librarian I had frequent official intercourse with Poe, but it was

at or near the close of the session before I met him in the social

circle. After spending an evening together at a private house he

invited me, on our return, into his room. It was a cold night in

December, and his fire having gone pretty nearly out, by the aid of

some tallow candles, and the fragments of a small table which he broke

up for the purpose, he soon rekindled it, and by its comfortable blaze

I spent a very pleasant hour with him. On this occasion he spoke with

regret of the large amount of money he had wasted, and of the debts he

had contracted during the session. If my memory be not at fault, he

estimated his indebtedness at $2,000 and, though they were gaming

debts, he was earnest and emphatic in the declaration that he was

bound by honor to pay them at the earliest opportunity."

This appears to have been Poe's last night at the university. He left it

never to return, yet, short as was his sojourn there, he left behind him

such honorable memories that his 'alma mater' is now only too proud to

enrol his name among her most respected sons. Poe's adopted father,

however, did not regard his 'prot間?s' collegiate career with equal

pleasure: whatever view he may have entertained of the lad's scholastic

successes, he resolutely refused to discharge the gambling debts which,

like too many of his classmates, he had incurred. A violent altercation

took place between Mr. Allan and the youth, and Poe hastily quitted the

shelter of home to try and make his way in the world alone.

Taking with him such poems as he had ready, Poe made his way to Boston,

and there looked up some of his mother's old theatrical friends. Whether

he thought of adopting the stage as a profession, or whether he thought

of getting their assistance towards helping him to put a drama of his

own upon the stage,--that dream of all young authors,--is now unknown.

He appears to have wandered about for some time, and by some means or

the other succeeded in getting a little volume of poems printed "for

private circulation only." This was towards the end of 1827, when he was

nearing nineteen. Doubtless Poe expected to dispose of his volume by

subscription among his friends, but copies did not go off, and

ultimately the book was suppressed, and the remainder of the edition,

for "reasons of a private nature," destroyed.

What happened to the young poet, and how he contrived to exist for the

next year or so, is a mystery still unsolved. It has always been

believed that he found his way to Europe and met with some curious

adventures there, and Poe himself certainly alleged that such was the

case. Numbers of mythical stories have been invented to account for this

chasm in the poet's life, and most of them self-evidently fabulous. In a

recent biography of Poe an attempt had been made to prove that he

enlisted in the army under an assumed name, and served for about

eighteen months in the artillery in a highly creditable manner,

receiving an honorable discharge at the instance of Mr. Allan. This

account is plausible, but will need further explanation of its many

discrepancies of dates, and verification of the different documents

cited in proof of it, before the public can receive it as fact. So many

fables have been published about Poe, and even many fictitious documents

quoted, that it behoves the unprejudiced to be wary in accepting any new

statements concerning him that are not thoroughly authenticated.

On the 28th February, 1829, Mrs. Allan died, and with her death the

final thread that had bound Poe to her husband was broken. The adopted

son arrived too late to take a last farewell of her whose influence had

given the Allan residence its only claim upon the poet's heart. A kind

of truce was patched up over the grave of the deceased lady, but, for

the future, Poe found that home was home no longer.

Again the young man turned to poetry, not only as a solace but as a

means of earning a livelihood. Again he printed a little volume of

poems, which included his longest piece, "Al Aaraaf," and several others

now deemed classic. The book was a great advance upon his previous

collection, but failed to obtain any amount of public praise or personal

profit for its author.

Feeling the difficulty of living by literature at the same time that he

saw he might have to rely largely upon his own exertions for a

livelihood, Poe expressed a wish to enter the army. After no little

difficulty a cadetship was obtained for him at the West Point Military

Academy, a military school in many respects equal to the best in Europe

for the education of officers for the army. At the time Poe entered the

Academy it possessed anything but an attractive character, the

discipline having been of the most severe character, and the

accommodation in many respects unsuitable for growing lads.

The poet appears to have entered upon this new course of life with his

usual enthusiasm, and for a time to have borne the rigid rules of the

place with unusual steadiness. He entered the institution on the 1st

July, 1830, and by the following March had been expelled for determined

disobedience. Whatever view may be taken of Poe's conduct upon this

occasion, it must be seen that the expulsion from West Point was of his

own seeking. Highly-colored pictures have been drawn of his eccentric

behavior at the Academy, but the fact remains that he wilfully, or at

any rate purposely, flung away his cadetship. It is surmised with

plausibility that the second marriage of Mr. Allan, and his expressed

intention of withdrawing his help and of not endowing or bequeathing

this adopted son any of his property, was the mainspring of Poe's

action. Believing it impossible to continue without aid in a profession

so expensive as was a military life, he determined to relinquish it and

return to his long cherished attempt to become an author.

Expelled from the institution that afforded board and shelter, and

discarded by his former protector, the unfortunate and penniless young

man yet a third time attempted to get a start in the world of letters by

means of a volume of poetry. If it be true, as alleged, that several of

his brother cadets aided his efforts by subscribing for his little work,

there is some possibility that a few dollars rewarded this latest

venture. Whatever may have resulted from the alleged aid, it is certain

that in a short time after leaving the Military Academy Poe was reduced

to sad straits. He disappeared for nearly two years from public notice,

and how he lived during that period has never been satisfactorily

explained. In 1833 he returns to history in the character of a winner of

a hundred-dollar award offered by a newspaper for the best story.

The prize was unanimously adjudged to Poe by the adjudicators, and Mr.

Kennedy, an author of some little repute, having become interested by

the young man's evident genius, generously assisted him towards

obtaining a livelihood by literary labor. Through his new friend's

introduction to the proprietor of the 'Southern Literary Messenger', a

moribund magazine published at irregular intervals, Poe became first a

paid contributor, and eventually the editor of the publication, which

ultimately he rendered one of the most respected and profitable

periodicals of the day. This success was entirely due to the brilliancy

and power of Poe's own contributions to the magazine.

In March, 1834, Mr. Allan died, and if our poet had maintained any hopes

of further assistance from him, all doubt was settled by the will, by

which the whole property of the deceased was left to his second wife and

her three sons. Poe was not named.

On the 6th May, 1836, Poe, who now had nothing but his pen to trust to,

married his cousin, Virginia Clemm, a child of only fourteen, and with

her mother as housekeeper, started a home of his own. In the meantime

his various writings in the 'Messenger' began to attract attention and

to extend his reputation into literary circles, but beyond his editorial

salary of about $520 brought him no pecuniary reward.

In January, 1837, for reasons never thoroughly explained, Poe severed

his connection with the 'Messenger', and moved with all his household

goods from Richmond to New York. Southern friends state that Poe was

desirous of either being admitted into partnership with his employer, or

of being allowed a larger share of the profits which his own labors

procured. In New York his earnings seem to have been small and

irregular, his most important work having been a republication from the

'Messenger' in book form of his Defoe-like romance entitled 'Arthur

Gordon Pym'. The truthful air of "The Narrative," as well as its other

merits, excited public curiosity both in England and America; but Poe's

remuneration does not appear to have been proportionate to its success,

nor did he receive anything from the numerous European editions the work

rapidly passed through.

In 1838 Poe was induced by a literary friend to break up his New York

home and remove with his wife and aunt (her mother) to Philadelphia. The

Quaker city was at that time quite a hotbed for magazine projects, and

among the many new periodicals Poe was enabled to earn some kind of a

living. To Burton's 'Gentleman's Magazine' for 1837 he had contributed a

few articles, but in 1840 he arranged with its proprietor to take up the

editorship. Poe had long sought to start a magazine of his own, and it

was probably with a view to such an eventuality that one of his

conditions for accepting the editorship of the 'Gentleman's Magazine'

was that his name should appear upon the title-page.

Poe worked hard at the 'Gentleman's' for some time, contributing to its

columns much of his best work; ultimately, however, he came to

loggerheads with its proprietor, Burton, who disposed of the magazine to

a Mr. Graham, a rival publisher. At this period Poe collected into two

volumes, and got them published as 'Tales of the Grotesque and

Arabesques', twenty-five of his stories, but he never received any

remuneration, save a few copies of the volumes, for the work. For some

time the poet strove most earnestly to start a magazine of his own, but

all his efforts failed owing to his want of capital.

The purchaser of Burton's magazine, having amalgamated it with another,

issued the two under the title of 'Graham's Magazine'. Poe became a

contributor to the new venture, and in November of the year 1840

consented to assume the post of editor.

Under Poe's management, assisted by the liberality of Mr. Graham,

'Graham's Magazine' became a grand success. To its pages Poe contributed

some of his finest and most popular tales, and attracted to the

publication the pens of many of the best contemporary authors. The

public was not slow in showing its appreciation of 'pabulum' put before

it, and, so its directors averred, in less than two years the

circulation rose from five to fifty-two thousand copies.

A great deal of this success was due to Poe's weird and wonderful

stories; still more, perhaps, to his trenchant critiques and his

startling theories anent cryptology. As regards the tales now issued in

'Graham's', attention may especially be drawn to the world-famed

"Murders in the Rue Morgue," the first of a series--'"une esp鑓e de

trilogie,"' as Baudelaire styles them--illustrative of an analytic phase

of Poe's peculiar mind. This 'trilogie' of tales, of which the later two

were "The Purloined Letter" and "The Mystery of Marie Roget," was

avowedly written to prove the capability of solving the puzzling riddles

of life by identifying another person's mind by our own. By trying to

follow the processes by which a person would reason out a certain thing,

Poe propounded the theory that another person might ultimately arrive,

as it were, at that person's conclusions, indeed, penetrate the

innermost arcanum of his brain and read his most secret thoughts. Whilst

the public was still pondering over the startling proposition, and

enjoying perusal of its apparent proofs, Poe still further increased his

popularity and drew attention to his works by putting forward the

attractive but less dangerous theorem that "human ingenuity could not

construct a cipher which human ingenuity could not solve."

This cryptographic assertion was made in connection with what the public

deemed a challenge, and Poe was inundated with ciphers more or less

abstruse, demanding solution. In the correspondence which ensued in

'Graham's Magazine' and other publications, Poe was universally

acknowledged to have proved his case, so far as his own personal ability

to unriddle such mysteries was concerned. Although he had never offered

to undertake such a task, he triumphantly solved every cryptogram sent

to him, with one exception, and that exception he proved conclusively

was only an imposture, for which no solution was possible.

The outcome of this exhaustive and unprofitable labor was the

fascinating story of "The Gold Bug," a story in which the discovery of

hidden treasure is brought about by the unriddling of an intricate

cipher.

The year 1841 may be deemed the brightest of Poe's checkered career. On

every side acknowledged to be a new and brilliant literary light, chief

editor of a powerful magazine, admired, feared, and envied, with a

reputation already spreading rapidly in Europe as well as in his native

continent, the poet might well have hoped for prosperity and happiness.

But dark cankers were gnawing his heart. His pecuniary position was

still embarrassing. His writings, which were the result of slow and

careful labor, were poorly paid, and his remuneration as joint editor of

'Graham's' was small. He was not permitted to have undivided control,

and but a slight share of the profits of the magazine he had rendered

world-famous, whilst a fearful domestic calamity wrecked all his hopes,

and caused him to resort to that refuge of the broken-hearted--to that

drink which finally destroyed his prospects and his life.

Edgar Poe's own account of this terrible malady and its cause was made

towards the end of his career. Its truth has never been disproved, and

in its most important points it has been thoroughly substantiated. To a

correspondent he writes in January 1848:

"You say, 'Can you _hint_ to me what was "that terrible evil" which

caused the "irregularities" so profoundly lamented?' Yes, I can do more

than hint. This _evil_ was the greatest which can befall a man. Six

years ago, a wife whom I loved as no man ever loved before, ruptured a

blood-vessel in singing. Her life was despaired of. I took leave of

her forever, and underwent all the agonies of her death. She recovered

partially, and I again hoped. At the end of a year, the vessel broke

again. I went through precisely the same scene.... Then again--again--

and even once again at varying intervals. Each time I felt all the

agonies of her death--and at each accession of the disorder I loved

her more dearly and clung to her life with more desperate pertinacity.

But I am constitutionally sensitive--nervous in a very unusual degree.

I became insane, with long intervals of horrible sanity. During these

fits of absolute unconsciousness, I drank--God only knows how often or

how much. As a matter of course, my enemies referred the insanity to

the drink rather than the drink to the insanity. I had, indeed, nearly

abandoned all hope of a permanent cure, when I found one in the

_death_ of my wife. This I can and do endure as becomes a man. It was

the horrible never-ending oscillation between hope and despair which I

could _not_ longer have endured, without total loss of reason."

The poet at this period was residing in a small but elegant little home,

superintended by his ever-faithful guardian, his wife's mother--his own

aunt, Mrs. Clemm, the lady whom he so gratefully addressed in after

years in the well-known sonnet, as "more than mother unto me." But a

change came o'er the spirit of his dream! His severance from 'Graham's',

owing to we know not what causes, took place, and his fragile schemes of

happiness faded as fast as the sunset. His means melted away, and he

became unfitted by mental trouble and ill-health to earn more. The

terrible straits to which he and his unfortunate beloved ones were

reduced may be comprehended after perusal of these words from Mr. A. B.

Harris's reminiscences.

Referring to the poet's residence in Spring Gardens, Philadelphia, this

writer says:

"It was during their stay there that Mrs. Poe, while singing one

evening, ruptured a blood-vessel, and after that she suffered a

hundred deaths. She could not bear the slightest exposure, and needed

the utmost care; and all those conveniences as to apartment and

surroundings which are so important in the case of an invalid were

almost matters of life and death to her. And yet the room where she

lay for weeks, hardly able to breathe, except as she was fanned, was a

little narrow place, with the ceiling so low over the narrow bed that

her head almost touched it. But no one dared to speak, Mr. Poe was so

sensitive and irritable; 'quick as steel and flint,' said one who knew

him in those days. And he would not allow a word about the danger of

her dying: the mention of it drove him wild."

Is it to be wondered at, should it not indeed be forgiven him, if,

impelled by the anxieties and privations at home, the unfortunate poet,

driven to the brink of madness, plunged still deeper into the Slough of

Despond? Unable to provide for the pressing necessities of his beloved

wife, the distracted man

"would steal out of the house at night, and go off and wander about

the street for hours, proud, heartsick, despairing, not knowing which

way to turn, or what to do, while Mrs. Clemm would endure the anxiety

at home as long as she could, and then start off in search of him."

During his calmer moments Poe exerted all his efforts to proceed with

his literary labors. He continued to contribute to 'Graham's Magazine,'

the proprietor of which periodical remained his friend to the end of his

life, and also to some other leading publications of Philadelphia and

New York. A suggestion having been made to him by N. P. Willis, of the

latter city, he determined to once more wander back to it, as he found

it impossible to live upon his literary earnings where he was.

Accordingly, about the middle of 1845, Poe removed to New York, and

shortly afterwards was engaged by Willis and his partner Morris as

sub-editor on the 'Evening Mirror'. He was, says Willis,

"employed by us for several months as critic and subeditor.... He

resided with his wife and mother at Fordham, a few miles out of town,

but was at his desk in the office from nine in the morning till the

evening paper went to press. With the highest admiration for his

genius, and a willingness to let it atone for more than ordinary

irregularity, we were led by common report to expect a very capricious

attention to his duties, and occasionally a scene of violence and

difficulty. Time went on, however, and he was invariably punctual and

industrious. With his pale, beautiful, and intellectual face, as a

reminder of what genius was in him, it was impossible, of course, not

to treat him always with deferential courtsey.... With a prospect of

taking the lead in another periodical, he at last voluntarily gave up

his employment with us."

A few weeks before Poe relinquished his laborious and ill-paid work on

the 'Evening Mirror', his marvellous poem of "The Raven" was published.

The effect was magical. Never before, nor, indeed, ever since, has a

single short poem produced such a great and immediate enthusiasm. It did

more to render its author famous than all his other writings put

together. It made him the literary lion of the season; called into

existence innumerable parodies; was translated into various languages,

and, indeed, created quite a literature of its own. Poe was naturally

delighted with the success his poem had attained, and from time to time

read it in his musical manner in public halls or at literary receptions.

Nevertheless he affected to regard it as a work of art only, and wrote

his essay entitled the "Philosophy of Composition," to prove that it was

merely a mechanical production made in accordance with certain set

rules.

Although our poet's reputation was now well established, he found it

still a difficult matter to live by his pen. Even when in good health,

he wrote slowly and with fastidious care, and when his work was done had

great difficulty in getting publishers to accept it. Since his death it

has been proved that many months often elapsed before he could get

either his most admired poems or tales published.

Poe left the 'Evening Mirror' in order to take part in the 'Broadway

Journal', wherein he re-issued from time to time nearly the whole of his

prose and poetry. Ultimately he acquired possession of this periodical,

but, having no funds to carry it on, after a few months of heartbreaking

labor he had to relinquish it. Exhausted in body and mind, the

unfortunate man now retreated with his dying wife and her mother to a

quaint little cottage at Fordham, outside New York. Here after a time

the unfortunate household was reduced to the utmost need, not even

having wherewith to purchase the necessities of life. At this dire

moment, some friendly hand, much to the indignation and dismay of Poe

himself, made an appeal to the public on behalf of the hapless family.

The appeal had the desired effect. Old friends and new came to the

rescue, and, thanks to them, and especially to Mrs. Shew, the "Marie

Louise" of Poe's later poems, his wife's dying moments were soothed, and

the poet's own immediate wants provided for. In January, 1846, Virginia

Poe died; and for some time after her death the poet remained in an

apathetic stupor, and, indeed, it may be truly said that never again did

his mental faculties appear to regain their former power.

For another year or so Poe lived quietly at Fordham, guarded by the

watchful care of Mrs. Clemm,--writing little, but thinking out his

philosophical prose poem of "Eureka," which he deemed the crowning work

of his life. His life was as abstemious and regular as his means were

small. Gradually, however, as intercourse with fellow literati

re-aroused his dormant energies, he began to meditate a fresh start in

the world. His old and never thoroughly abandoned project of starting a

magazine of his own, for the enunciation of his own views on literature,

now absorbed all his thoughts. In order to get the necessary funds for

establishing his publication on a solid footing, he determined to give a

series of lectures in various parts of the States.

His re-entry into public life only involved him in a series of

misfortunes. At one time he was engaged to be married to Mrs. Whitman, a

widow lady of considerable intellectual and literary attainments; but,

after several incidents of a highly romantic character, the match was

broken off. In 1849 Poe revisited the South, and, amid the scenes and

friends of his early life, passed some not altogether unpleasing time.

At Richmond, Virginia, he again met his first love, Elmira, now a

wealthy widow, and, after a short renewed acquaintance, was once more

engaged to marry her. But misfortune continued to dog his steps.

A publishing affair recalled him to New York. He left Richmond by boat

for Baltimore, at which city he arrived on the 3d October, and handed

his trunk to a porter to carry to the train for Philadelphia. What now

happened has never been clearly explained. Previous to starting on his

journey, Poe had complained of indisposition,--of chilliness and of

exhaustion,--and it is not improbable that an increase or continuance of

these symptoms had tempted him to drink, or to resort to some of those

narcotics he is known to have indulged in towards the close of his life.

Whatever the cause of his delay, the consequences were fatal. Whilst in

a state of temporary mania or insensibility, he fell into the hands of a

band of ruffians, who were scouring the streets in search of accomplices

or victims. What followed is given on undoubted authority.

His captors carried the unfortunate poet into an electioneering den,

where they drugged him with whisky. It was election day for a member of

Congress, and Poe with other victims, was dragged from polling station

to station, and forced to vote the ticket placed in his hand. Incredible

as it may appear, the superintending officials of those days registered

the proffered vote, quite regardless of the condition of the person

personifying a voter. The election over, the dying poet was left in the

streets to perish, but, being found ere life was extinct, he was carried

to the Washington University Hospital, where he expired on the 7th of

October, 1849, in the forty-first year of his age.

Edgar Poe was buried in the family grave of his grandfather, General

Poe, in the presence of a few friends and relatives. On the 17th

November, 1875, his remains were removed from their first resting-place

and, in the presence of a large number of people, were placed under a

marble monument subscribed for by some of his many admirers. His wife's

body has recently been placed by his side.

The story of that "fitful fever" which constituted the life of Edgar Poe

leaves upon the reader's mind the conviction that he was, indeed, truly

typified by that:

"Unhappy master, whom unmerciful disaster

Followed fast and followed faster till his songs one burden

bore--

Till the dirges of his hope that melancholy burden bore

Of 'Never--nevermore.'"

JOHN H. INGRAM.

* * * * *

POEMS OF LATER LIFE

TO

THE NOBLEST OF HER SEX--

TO THE AUTHOR OF

"THE DRAMA OF EXILE"--

TO

MISS ELIZABETH BARRETT BARRETT,

OF ENGLAND,

I DEDICATE THIS VOLUME

WITH THE MOST ENTHUSIASTIC ADMIRATION AND

WITH THE MOST SINCERE ESTEEM.

1845 E.A.P.

* * * * *

PREFACE.

These trifles are collected and republished chiefly with a view to their

redemption from the many improvements to which they have been subjected

while going at random the "rounds of the press." I am naturally anxious

that what I have written should circulate as I wrote it, if it circulate

at all. In defence of my own taste, nevertheless, it is incumbent upon

me to say that I think nothing in this volume of much value to the

public, or very creditable to myself. Events not to be controlled have

prevented me from making, at any time, any serious effort in what, under

happier circumstances, would have been the field of my choice. With me

poetry has been not a purpose, but a passion; and the passions should be

held in reverence: they must not--they cannot at will be excited, with

an eye to the paltry compensations, or the more paltry commendations, of

mankind.

1845. E.A.P.

* * * * *

THE RAVEN.

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore--

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping--rapping at my chamber door.

"'Tis some visitor," I muttered, "tapping at my chamber door--

Only this and nothing more."

Ah, distinctly I remember, it was in the bleak December,

And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor.

Eagerly I wished the morrow;--vainly I had sought to borrow

From my books surcease of sorrow--sorrow for the lost Lenore--

For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore--

Nameless here for evermore.

And the silken sad uncertain rustling of each purple curtain

Thrilled me--filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before;

So that now, to still the beating of my heart, I stood repeating

"'Tis some visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door--

Some late visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door;--

This it is and nothing more."

Presently my soul grew stronger; hesitating then no longer,

"Sir," said I, "or Madam, truly your forgiveness I implore;

But the fact is I was napping, and so gently you came rapping,

And so faintly you came tapping--tapping at my chamber door,

That I scarce was sure I heard you"--here I opened wide the door:--

Darkness there and nothing more.

Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there wondering,

fearing,

Doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before;

But the silence was unbroken, and the darkness gave no token,

And the only word there spoken was the whispered word, "Lenore!"

This I whispered, and an echo murmured back the word, "Lenore!"

Merely this and nothing more.

Back into the chamber turning, all my soul within me burning,

Soon I heard again a tapping, somewhat louder than before.

"Surely," said I, "surely that is something at my window lattice;

Let me see, then, what thereat is, and this mystery explore--

Let my heart be still a moment, and this mystery explore;--

'Tis the wind and nothing more."

Open here I flung the shutter, when, with many a flirt and flutter,

In there stepped a stately Raven of the saintly days of yore;

Not the least obeisance made he: not an instant stopped or stayed he;

But, with mien of lord or lady, perched above my chamber door--

Perched upon a bust of Pallas just above my chamber door--

Perched, and sat, and nothing more.

Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling,

By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore,

"Though thy crest be shorn and shaven, thou," I said, "art sure no

craven,

Ghastly grim and ancient Raven wandering from the Nightly shore--

Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night's Plutonian shore!"

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore."

Much I marvelled this ungainly fowl to hear discourse so plainly,

Though its answer little meaning--little relevancy bore;

For we cannot help agreeing that no living human being

Ever yet was blessed with seeing bird above his chamber door--

Bird or beast upon the sculptured bust above his chamber door,

With such name as "Nevermore."

But the Raven, sitting lonely on that placid bust, spoke only

That one word, as if his soul in that one word he did outpour.

Nothing further then he uttered--not a feather then he fluttered--

Till I scarcely more than muttered, "Other friends have flown before--

On the morrow _he_ will leave me, as my hopes have flown before."

Then the bird said, "Nevermore."

Startled at the stillness broken by reply so aptly spoken,

"Doubtless," said I, "what it utters is its only stock and store,

Caught from some unhappy master whom unmerciful Disaster

Followed fast and followed faster till his songs one burden bore--

Till the dirges of his Hope the melancholy burden bore

Of 'Never--nevermore.'"

But the Raven still beguiling all my sad soul into smiling,

Straight I wheeled a cushioned seat in front of bird and bust and

door;

Then, upon the velvet sinking, I betook myself to linking

Fancy unto fancy, thinking what this ominous bird of yore--

What this grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt, and ominous bird of yore

Meant in croaking "Nevermore."

This I sat engaged in guessing, but no syllable expressing

To the fowl whose fiery eyes now burned into my bosom's core;

This and more I sat divining, with my head at ease reclining

On the cushion's velvet lining that the lamp-light gloated o'er,

But whose velvet violet lining with the lamp-light gloating o'er,

_She_ shall press, ah, nevermore!

Then, methought, the air grew denser, perfumed from an unseen censer

Swung by Seraphim whose foot-falls tinkled on the tufted floor.

"Wretch," I cried, "thy God hath lent thee--by these angels he hath

sent thee

Respite--respite aad nepenth?from thy memories of Lenore!

Quaff, oh quaff this kind nepenth? and forget this lost Lenore!"

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore."

"Prophet!" said I, "thing of evil!--prophet still, if bird or devil!--

Whether Tempter sent, or whether tempest tossed thee here ashore,

Desolate yet all undaunted, on this desert land enchanted--

On this home by Horror haunted--tell me truly, I implore--

Is there--_is_ there balm in Gilead?--tell me--tell me, I implore!"

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore."

"Prophet!" said I, "thing of evil!--prophet still, if bird or devil!

By that Heaven that bends above us--by that God we both adore--

Tell this soul with sorrow laden if, within the distant Aidenn,

It shall clasp a sainted maiden whom the angels name Lenore--

Clasp a rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore."

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore."

"Be that word our sign of parting, bird or fiend!" I shrieked,

upstarting--

"Get thee back into the tempest and the Night's Plutonian shore!

Leave no black plume as a token of that lie thy soul hath spoken!

Leave my loneliness unbroken!--quit the bust above my door!

Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!"

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore."

And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting

On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door;

And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon's that is dreaming,

And the lamp-light o'er him streaming throws his shadow on the floor;

And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor

Shall be lifted--nevermore!

Published, 1845.

* * * * *

THE BELLS,

I.

Hear the sledges with the bells--

Silver bells!

What a world of merriment their melody foretells!

How they tinkle, tinkle, tinkle,

In their icy air of night!

While the stars, that oversprinkle

All the heavens, seem to twinkle

With a crystalline delight;

Keeping time, time, time,

In a sort of Runic rhyme,

To the tintinnabulation that so musically wells

From the bells, bells, bells, bells,

Bells, bells, bells--

From the jingling and the tinkling of the bells.

II.

Hear the mellow wedding bells,

Golden bells!

What a world of happiness their harmony foretells!

Through the balmy air of night

How they ring out their delight!

From the molten golden-notes,

And all in tune,

What a liquid ditty floats

To the turtle-dove that listens, while she gloats

On the moon!

Oh, from out the sounding cells,

What a gush of euphony voluminously wells!

How it swells!

How it dwells

On the future! how it tells

Of the rapture that impels

To the swinging and the ringing

Of the bells, bells, bells,

Of the bells, bells, bells, bells,

Bells, bells, bells--

To the rhyming and the chiming of the bells!

III.

Hear the loud alarum bells--

Brazen bells!

What a tale of terror now their turbulency tells!

In the startled ear of night

How they scream out their affright!

Too much horrified to speak,

They can only shriek, shriek,

Out of tune,

In a clamorous appealing to the mercy of the fire,

In a mad expostulation with the deaf and frantic fire

Leaping higher, higher, higher,

With a desperate desire,

And a resolute endeavor

Now--now to sit or never,

By the side of the pale-faced moon.

Oh, the bells, bells, bells!

What a tale their terror tells

Of Despair!

How they clang, and clash, and roar!

What a horror they outpour

On the bosom of the palpitating air!

Yet the ear it fully knows,

By the twanging,

And the clanging,

How the danger ebbs and flows;

Yet the ear distinctly tells,

In the jangling,

And the wrangling,

How the danger sinks and swells,

By the sinking or the swelling in the anger of the bells--

Of the bells--

Of the bells, bells, bells, bells,

Bells, bells, bells--

In the clamor and the clangor of the bells!

IV.

Hear the tolling of the bells--

Iron bells!

What a world of solemn thought their monody compels!

In the silence of the night,

How we shiver with affright

At the melancholy menace of their tone!

For every sound that floats

From the rust within their throats

Is a groan.

And the people--ah, the people--

They that dwell up in the steeple.

All alone,

And who toiling, toiling, toiling,

In that muffled monotone,

Feel a glory in so rolling

On the human heart a stone--

They are neither man nor woman--

They are neither brute nor human--

They are Ghouls:

And their king it is who tolls;

And he rolls, rolls, rolls,

Rolls

A p鎍n from the bells!

And his merry bosom swells

With the p鎍n of the bells!

And he dances, and he yells;

Keeping time, time, time,

In a sort of Runic rhyme,

To the p鎍n of the bells--

Of the bells:

Keeping time, time, time,

In a sort of Runic rhyme,

To the throbbing of the bells--

Of the bells, bells, bells--

To the sobbing of the bells;

Keeping time, time, time,

As he knells, knells, knells,

In a happy Runic rhyme,

To the rolling of the bells--

Of the bells, bells, bells--

To the tolling of the bells,

Of the bells, bells, bells, bells,

Bells, bells, bells--

To the moaning and the groaning of the bells.

1849.

* * * * *

ULALUME.

The skies they were ashen and sober;

The leaves they were crisped and sere--

The leaves they were withering and sere;

It was night in the lonesome October

Of my most immemorial year;

It was hard by the dim lake of Auber,

In the misty mid region of Weir--

It was down by the dank tarn of Auber,

In the ghoul-haunted woodland of Weir.

Here once, through an alley Titanic.

Of cypress, I roamed with my Soul--

Of cypress, with Psyche, my Soul.

These were days when my heart was volcanic

As the scoriac rivers that roll--

As the lavas that restlessly roll

Their sulphurous currents down Yaanek

In the ultimate climes of the pole--

That groan as they roll down Mount Yaanek

In the realms of the boreal pole.

Our talk had been serious and sober,

But our thoughts they were palsied and sere--

Our memories were treacherous and sere--

For we knew not the month was October,

And we marked not the night of the year--

(Ah, night of all nights in the year!)

We noted not the dim lake of Auber--

(Though once we had journeyed down here)--

Remembered not the dank tarn of Auber,

Nor the ghoul-haunted woodland of Weir.

And now as the night was senescent

And star-dials pointed to morn--

As the sun-dials hinted of morn--

At the end of our path a liquescent

And nebulous lustre was born,

Out of which a miraculous crescent

Arose with a duplicate horn--

Astarte's bediamonded crescent

Distinct with its duplicate horn.

And I said--"She is warmer than Dian:

She rolls through an ether of sighs--

She revels in a region of sighs:

She has seen that the tears are not dry on

These cheeks, where the worm never dies,

And has come past the stars of the Lion

To point us the path to the skies--

To the Lethean peace of the skies--

Come up, in despite of the Lion,

To shine on us with her bright eyes--

Come up through the lair of the Lion,

With love in her luminous eyes."

But Psyche, uplifting her finger,

Said--"Sadly this star I mistrust--

Her pallor I strangely mistrust:--

Oh, hasten!--oh, let us not linger!

Oh, fly!--let us fly!--for we must."

In terror she spoke, letting sink her

Wings till they trailed in the dust--

In agony sobbed, letting sink her

Plumes till they trailed in the dust--

Till they sorrowfully trailed in the dust.

I replied--"This is nothing but dreaming:

Let us on by this tremulous light!

Let us bathe in this crystalline light!

Its Sibyllic splendor is beaming

With Hope and in Beauty to-night:--

See!--it flickers up the sky through the night!

Ah, we safely may trust to its gleaming,

And be sure it will lead us aright--

We safely may trust to a gleaming

That cannot but guide us aright,

Since it flickers up to Heaven through the night."

Thus I pacified Psyche and kissed her,

And tempted her out of her gloom--

And conquered her scruples and gloom;

And we passed to the end of a vista,

But were stopped by the door of a tomb--

By the door of a legended tomb;

And I said--"What is written, sweet sister,

On the door of this legended tomb?"

She replied--"Ulalume--Ulalume--

'Tis the vault of thy lost Ulalume!"

Then my heart it grew ashen and sober

As the leaves that were crisped and sere--

As the leaves that were withering and sere;

And I cried--"It was surely October

On _this_ very night of last year

That I journeyed--I journeyed down here--

That I brought a dread burden down here!

On this night of all nights in the year,

Ah, what demon has tempted me here?

Well I know, now, this dim lake of Auber--

This misty mid region of Weir--

Well I know, now, this dank tarn of Auber,--

This ghoul-haunted woodland of Weir."

1847.

* * * * *

TO HELEN.

I saw thee once--once only--years ago:

I must not say _how_ many--but _not_ many.

It was a July midnight; and from out

A full-orbed moon, that, like thine own soul, soaring,

Sought a precipitate pathway up through heaven,

There fell a silvery-silken veil of light,

With quietude, and sultriness and slumber,

Upon the upturn'd faces of a thousand

Roses that grew in an enchanted garden,

Where no wind dared to stir, unless on tiptoe--

Fell on the upturn'd faces of these roses

That gave out, in return for the love-light,

Their odorous souls in an ecstatic death--

Fell on the upturn'd faces of these roses

That smiled and died in this parterre, enchanted

By thee, and by the poetry of thy presence.

Clad all in white, upon a violet bank

I saw thee half-reclining; while the moon

Fell on the upturn'd faces of the roses,

And on thine own, upturn'd--alas, in sorrow!

Was it not Fate, that, on this July midnight--

Was it not Fate (whose name is also Sorrow),

That bade me pause before that garden-gate,

To breathe the incense of those slumbering roses?

No footstep stirred: the hated world all slept,

Save only thee and me--(O Heaven!--O God!

How my heart beats in coupling those two words!)--

Save only thee and me. I paused--I looked--

And in an instant all things disappeared.

(Ah, bear in mind this garden was enchanted!)

The pearly lustre of the moon went out:

The mossy banks and the meandering paths,

The happy flowers and the repining trees,

Were seen no more: the very roses' odors

Died in the arms of the adoring airs.

All--all expired save thee--save less than thou:

Save only the divine light in thine eyes--

Save but the soul in thine uplifted eyes.

I saw but them--they were the world to me.

I saw but them--saw only them for hours--

Saw only them until the moon went down.

What wild heart-histories seemed to lie unwritten

Upon those crystalline, celestial spheres!

How dark a woe! yet how sublime a hope!

How silently serene a sea of pride!