| First Name: | 李耳 | ||||

| Name and Alias: | 伯阳 | ||||

Read works of Lao-Tzu at 百家争鸣 Read works of Lao-Tzu at 诗海 | |||||

There are many popular accounts of Laozi's life, though facts and myths are impossible to separate regarding him. He is traditionally regarded as an older contemporary of Confucius, but modern scholarship places him centuries later or questions if he ever existed as an individual. Laozi is regarded as the author of the Dao De Jing, though it has been debated throughout history whether he authored it.

In legends, he was conceived when his mother gazed upon a falling star. It is said that he stayed in the womb and matured for sixty-two years. He was born when his mother leaned against a plum tree. He emerged a grown man with a full grey beard and long earlobes, which are a sign of wisdom and long life.

According to popular biographies, he worked as the Keeper of the Archives for the royal court of Chou. This allowed him broad access to the works of the Yellow Emperor and other classics of the time. Laozi never opened a formal school. Nonetheless, he attracted a large number of students and loyal disciples. There are numerous variations of a story depicting Confucius consulting Laozi about rituals.

Laozi is said to have married and had a son named Tsung, who was a celebrated soldier. A large number of people trace their lineage back to Laozi, as the T'ang Dynasty did. Many, or all, of the lineages may be inaccurate. However, they are a testament to the impact of Laozi on Chinese culture.

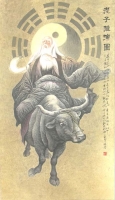

Traditional accounts state that Laozi grew weary of the moral decay of the city and noted the kingdom's decline. At the age of 160, he ventured west to live as a hermit in the unsettled frontier. At the western gate of the city, or kingdom, he was recognized by a guard. The sentry asked the old master to produce a record of his wisdom. The resulting book is said to be the Tao Te Ching. In some versions of the tale, the sentry is so touched by the work that he leaves with Laozi to never be seen again. Some legends elaborate further that the "Old Master" was the teacher of the Buddha, or the Buddha himself.

Laozi is an honorific title. Lao means "venerable" or "old". Zi, or tzu, means "master". Zi was used in ancient China like a social prefix, indicating "Master", or "Sir". In popular biogaphies, Laozi's given name was Er, his surname was Li and his courtesy name was Boyang. Dan is a posthumous name given to Laozi.

During the Tang Dynasty, he was honoured as an ancestor of the dynasty after Taoists drew a connection between the dynasty's family name of Li and Laozi's bearing of the same name. He was granted the title Taishang xuanyuan huangdi, meaning Supreme Mysterious and Primordial Emperor. Xuanyuan and Huangdi are also, respectively, the personal and proper names of the Yellow Emperor.

Laozi's work, the Tao Te Ching, is one of the most significant treatises in Chinese philosophy. It is his magnum opus, covering large areas of philosophy from individual spirituality and inter-personal dynamics to political techniques. The Tao Te Ching is said to contain 'hidden' instructions for Taoist adepts (often in the form of metaphors) relating to Taoist meditation and breathing.

Laozi developed the concept of "Tao", often translated as "the Way", and widened its meaning to an inherent order or property of the universe: "The way Nature is". He highlighted the concept of wu wei, or "do nothing". This does not mean that one should hang around and do nothing, but that one should avoid explicit intentions, strong wills or proactive initiatives.

Laozi believed that violence should be avoided as much as possible, and that military victory should be an occasion for mourning rather than triumphant celebration.

Laozi said that the codification of laws and rules created difficulty and complexity in managing and governing.

As with most other ancient Chinese philosophers, Laozi often explains his ideas by way of paradox, analogy, appropriation of ancient sayings, repetition, symmetry, rhyme, and rhythm. The writings attributed to him are often very dense and poetic. They serve as a starting point for cosmological or introspective meditations. Many of the aesthetic theories of Chinese art are widely grounded in his ideas and those of his most famous follower Zhuang Zi.

Potential officials throughout Chinese history drew on the authority of non-Confucian sages, especially Laozi and Zhuangzi, to deny serving any ruler at any time. Zhuangzi, Laozi's most famous follower, had a great deal of influence on Chinese literati and culture. Zhuangzi is a central authority regarding eremitism, a particular variation of monasticism sacrificing social aspects for religious aspects of life. Zhuangzi considered eremitism the highest ideal, if properly understood.

Scholars such as Aat Vervoom have postulated that Zhuangzi advocated a hermit immersed in society. This view of eremitism holds that seclusion is hiding anonymously in society. To a Zhuangzi hermit, being unknown and drifting freely is a state of mind. This reading is based on the "inner chapters" of Zhuangzi.

Scholars such as James Bellamy hold that this could be true and has been interpreted similarly at various points in Chinese history. However, the "outer chapters" of Zhuangzi have historically played a pivotal role in the advocacy of reclusion. While some scholars state that Laozi was the central figure of Han Dynasty eremitism, historical texts do not seem to support that position.

Political theorists influenced by Laozi have advocated humility in leadership and a restrained approach to statecraft, either for ethical and pacifist reasons, or for tactical ends. In a different context, various anti-authoritarian movements have embraced the Laozi teachings on the power of the weak.

The Anarcho-capitalist economist Murray N. Rothbard suggests that Laozi was the first libertarian, likening Laozi's ideas on government to F.A. Hayek's theory of spontaneous order. Similarly, the Cato Institute's David Boaz includes passages from the Tao Te Ching in his 1997 book The Libertarian Reader. Philosopher Roderick Long, however, argues that libertarian themes in Taoist thought are actually borrowed from earlier Confucian writers.

![老子- 维基百科,自由的百科全书 [编辑] 道教中的老子](http://oson.ca/upload/images11/cache/bd6f091d0f884e90c11c57677b27d48c.jpg)