20200705

注解: 手指向下或右滑,翻到下一页,向上或左滑,到上一页。

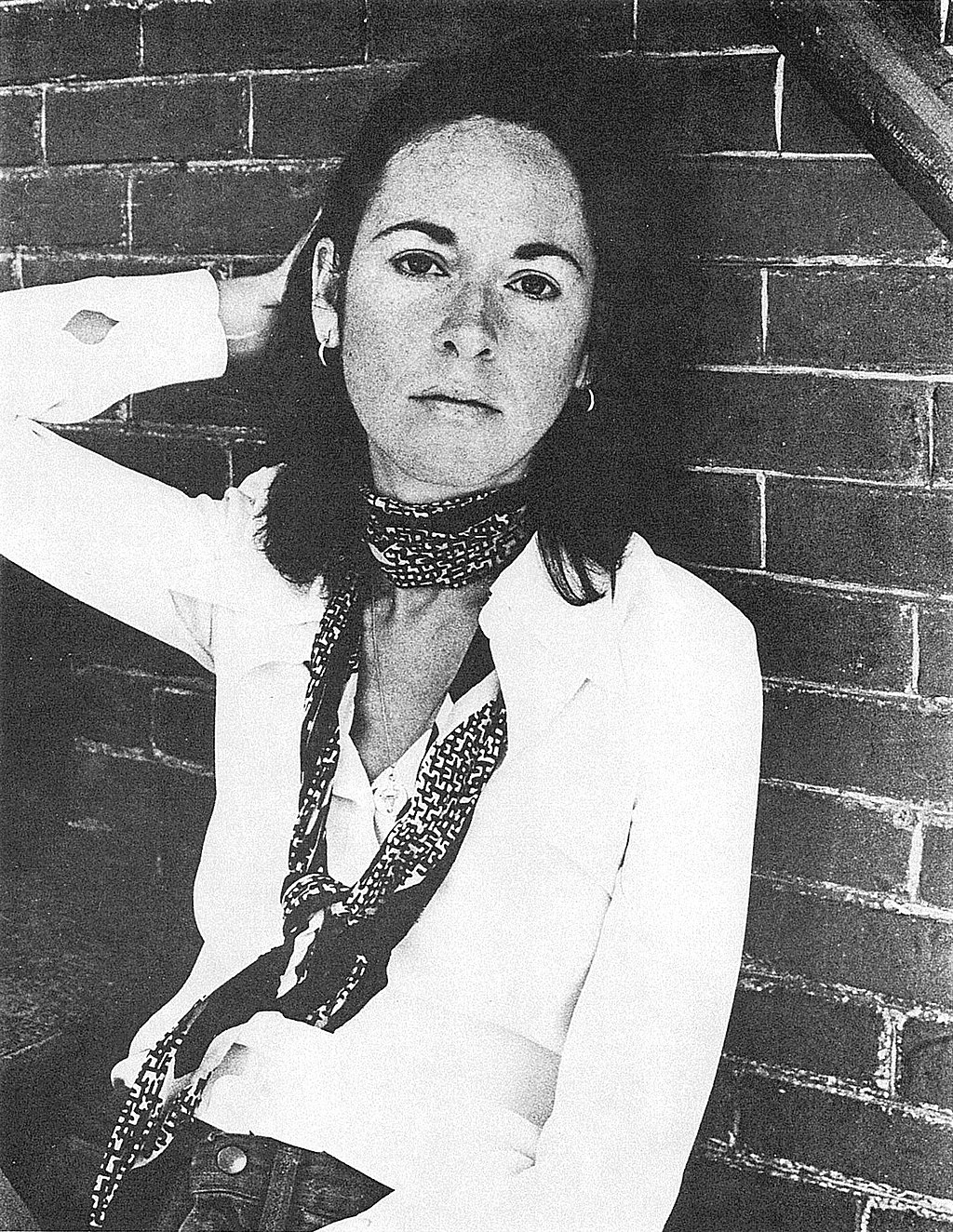

露易丝·格丽克

露易丝·格丽克(Louise Glück,1943— ),美国桂冠诗人,生于一个匈牙利裔犹太人家庭,1968年出版处女诗集《头生子》,至今著有十二本诗集和一本诗随笔集。格丽克的诗长于对心理隐微之处的把握,早期作品具有很强的自传性,后来的作品则通过人神对质,以及对神话人物的心理分析,导向人的存在根本问题,爱、死亡、生命、毁灭。自《阿勒山》开始,她的每部诗集都是精巧的织体,可作为一首长诗或一部组诗。从《阿勒山》和《野鸢尾》开始,格丽克成了“必读的诗人”。

Louise Elisabeth Glück (born April 22, 1943) is an American poet and essayist. One of the most prominent American poets of her generation, she has won many major literary awards in the United States, including the National Humanities Medal, Pulitzer Prize, National Book Award, National Book Critics Circle Award, and Bollingen Prize, among others. From 2003 to 2004, she was Poet Laureate of the United States. Glück is often described as an autobiographical poet; her work is known for its emotional intensity and for frequently drawing on myth, history, or nature to meditate on personal experiences and modern life.

Glück was born in New York City and raised on New York's Long Island. She began to suffer from anorexia nervosa while in high school and later overcame the illness. She took classes at Sarah Lawrence College and Columbia University but did not obtain a degree. In addition to her career as an author, she has had a career in academia as a teacher of poetry at several institutions.

In her work, Glück has focused on illuminating aspects of trauma, desire, and nature. In exploring these broad themes, her poetry has become known for its frank expressions of sadness and isolation. Scholars have also focused on her construction of poetic personas and the relationship, in her poems, between autobiography and classical myth.

Currently, Glück is an adjunct professor and Rosenkranz Writer in Residence at Yale University. She lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[1]

Biography

Early life

Louise Glück was born in New York City on April 22, 1943. She is the eldest of two surviving daughters of Daniel Glück, a businessman, and Beatrice Glück (née Grosby), a homemaker.[2]

Glück's paternal grandparents, Hungarian Jews, emigrated to the United States, where they eventually owned a grocery store in New York. Glück's father was the first member of his family born in the United States. He had an ambition to become a writer, but went into business with his brother-in-law.[3] Together, they achieved success when they invented the X-Acto Knife.[4] Glück's mother was a graduate of Wellesley College. From an early age, Glück received from her parents an education in Greek mythology and classic stories such as the legend of Joan of Arc.[5] She began to write poetry at an early age.[6]

As a teenager, Glück developed anorexia nervosa, which became the defining challenge of her late teenage and young adult years. She has described the illness, in one essay, as the result of an effort to assert her independence from her mother.[7] Elsewhere, she has connected her illness to the death of an elder sister, an event that occurred before she was born.[2] During the fall of her senior year at George W. Hewlett High School, in Hewlett, New York, she began psychoanalytic treatment. A few months later, she was taken out of school in order to focus on her rehabilitation, although she still graduated in 1961.[8] Of that decision, she has written, "I understood that at some point I was going to die. What I knew more vividly, more viscerally, was that I did not want to die".[7] She spent the next seven years in therapy, which she has credited with helping her to overcome the illness and teaching her how to think.[9]

As a result of her condition, Glück did not enroll in college as a full-time student. She has described her decision to forgo higher education in favor of therapy as necessary: "…my emotional condition, my extreme rigidity of behavior and frantic dependence on ritual made other forms of education impossible".[10] Instead, she took a poetry class at Sarah Lawrence College and, from 1963 to 1965, she enrolled in poetry workshops at Columbia University's School of General Education, which offered programs for non-traditional students.[11][12] While there, she studied with Léonie Adams and Stanley Kunitz. She has credited these teachers as significant mentors in her development as a poet.[13]

Career

After leaving Columbia without a degree, Glück supported herself with secretarial work.[14] She married Charles Hertz, Jr., in 1967. The marriage ended in divorce.[15] In 1968, Glück published her first collection of poems, Firstborn, which received some positive critical attention. However, she then experienced a prolonged case of writer's block, which was only cured, she has claimed, after 1971, when she began to teach poetry at Goddard College in Vermont.[14][16] The poems she wrote during this time were collected in her second book, The House on Marshland (1975), which many critics have regarded as her breakthrough work, signaling her "discovery of a distinctive voice".[17]

In 1973, Glück gave birth to a son, Noah, with her partner, John Dranow, an author who had started the summer writing program at Goddard College.[17][18] In 1977, she and Dranow were married.[15] In 1980, Dranow and Francis Voigt, the husband of poet Ellen Bryant Voigt, co-founded the New England Culinary Institute as a private, for-profit college. Glück and Bryant Voigt were early investors in the institute and served on its board of directors.[18]

In 1980, Glück's third collection, Descending Figure, was published. It received some criticism for its tone and subject matter: for example, the poet Greg Kuzma accused Glück of being a "child hater" for her now widely anthologized poem, "The Drowned Children".[19] On the whole, however, the book was well received. In the same year, a fire destroyed Glück's house in Vermont, resulting in the loss of all of her possessions.[15] In the wake of that tragedy, Glück began to write the poems that would later be collected in her award-winning work, The Triumph of Achilles (1985). Writing in The New York Times, the author and critic Liz Rosenberg described the collection as "clearer, purer, and sharper" than Glück's previous work.[20] The critic Peter Stitt, writing in The Georgia Review, declared that the book showed Glück to be "among the important poets of our age".[21] From the collection, the poem "Mock Orange", which has been likened to a feminist anthem,[22] has been called an "anthology piece" for how frequently it has appeared in poetry anthologies and college courses.[23]

In 1984, Glück joined the faculty of Williams College in Massachusetts as a senior lecturer in the English Department.[24] The following year, her father died.[25] The loss prompted her to begin a new collection of poems, Ararat (1990), the title of which references the mountain of the Genesis flood narrative. Writing in The New York Times in 2012, the critic Dwight Garner called it "the most brutal and sorrow-filled book of American poetry published in the last 25 years".[26] Glück then followed this collection in 1992 with one of her most popular and critically acclaimed books, The Wild Iris, which, in its poems, features garden flowers in conversation with a gardener and a deity about the nature of life. Publishers Weekly proclaimed it an "important book" that showcased "poetry of great beauty".[27] The critic Elizabeth Lund, writing in The Christian Science Monitor, called it "a milestone work".[28] It went on to win the Pulitzer Prize in 1993, cementing Glück's reputation as a preeminent American poet.

While the 1990s brought Glück literary success, it was also a period of personal hardship. Her marriage to John Dranow ended in divorce, the difficult nature of which affected their business relationship, resulting in Dranow's removal from his positions at the New England Culinary Institute.[18] Glück channeled her experience into her writing, entering a prolific period of her career. In 1994, she published a collection of essays called Proofs & Theories: Essays on Poetry. She then produced Meadowlands (1996), a collection of poetry about the nature of love and the deterioration of a marriage. She followed it with two more collections: Vita Nova (1999) and The Seven Ages (2001).

In 2004, in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Glück published a book-length poem entitled October. Divided into six parts, the poem draws on ancient Greek myth to explore aspects of trauma and suffering.[29] That same year, she was named the Rosenkranz Writer in Residence at Yale University.[30]

Since joining the faculty of Yale, Glück has continued to publish poetry. Her books published during this period include Averno (2006), A Village Life (2009), and Faithful and Virtuous Night (2014). In 2012, the publication of a collection of a half-century's worth of her poems, entitled Poems: 1962-2012, was called "a literary event".[31] Another collection of her essays, entitled American Originality, appeared in 2017.

Family

Glück has been divorced twice. Her first marriage was to Charles Hertz, Jr. Her second marriage was to John Dranow, a writer, professor, and entrepreneur.[32] She has one son, Noah Dranow, who trained as a sommelier and lives in San Francisco.[4]

Glück's elder sister died young before Glück was born. Her younger sister, Tereze, spent her career with Citibank as a vice president and was also an award-winning author of fiction. Glück's niece is the actress Abigail Savage.[33]

Honors[edit]

Glück has received numerous honors for her work. In addition to most of the major awards for poetry in the United States, she has received multiple fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation. Below are honors she has received for both her body of work and individual works

Honors for body of work

- National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship (1970)[34]

- Guggenheim Fellowship for Creative Arts (1975)[35]

- National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship (1979)

- American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in Literature (1981)[36]

- Guggenheim Fellowship for Creative Arts (1987)

- National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship (1988)

- Honorary Doctorate, Williams College (1993)[37]

- American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Elected Member (1993)[38]

- Vermont State Poet (1994-1998)[39]

- Honorary Doctorate, Middlebury College (1996)[40]

- American Academy of Arts and Letters, Elected Member (1996)[41]

- Lannan Literary Award (1999)[42]

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences 50th Anniversary Medal, MIT (2001)[43]

- Bollingen Prize (2001)[44]

- Poet Laureate of the United States (2003-2004)[45]

- Wallace Stevens Award of the Academy of American Poets (2008)[46]

- Aiken Taylor Award for Modern American Poetry (2010)[47]

- American Academy of Achievement, Elected Member (2012)[48]

- American Philosophical Society, Elected Member (2014)[49]

- American Academy of Arts and Letters Gold Medal in Poetry (2015)[50]

- National Humanities Medal (2015)[51]

- Tranströmer Prize (2020)[52]

Honors for individual works

- Melville Cane Award for The Triumph of Achilles (1985)[53]

- National Book Critics Circle Award for The Triumph of Achilles (1985)[54]

- Rebekah Johnson Bobbitt National Prize for Poetry for Ararat (1992)[55]

- William Carlos Williams Award for The Wild Iris (1993)[12]

- Pulitzer Prize for The Wild Iris (1993)[56]

- PEN/Martha Albrand Award for First Nonfiction for Proofs & Theories: Essays on Poetry (1995)[57]

- Ambassador Book Award of the English-Speaking Union for Vita Nova (2000)[58]

- Ambassador Book Award of the English-Speaking Union for Averno (2007)[59]

- L.L. Winship/PEN New England Award for Averno (2007)[60]

- Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Poems 1962-2012 (2012)[61]

- National Book Award for Faithful and Virtuous Night (2014)[62]

In addition, The Wild Iris, Vita Nova, and Averno were all finalists for the National Book Award.[63] The Seven Ages was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award.[64][54] A Village Life was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Griffin International Poetry Prize.[65]

Glück's poems have been widely anthologized, including in the Norton Anthology of Poetry,[66] the Oxford Book of American Poetry,[67] and the Columbia Anthology of American Poetry.[68]

Elected or invited posts

In 1999, Glück, along with the poets Rita Dove and W.S. Merwin, was asked to serve as a special consultant to the Library of Congress for that institution's bicentennial. In this capacity, she helped the Library of Congress to determine programming to mark its 200th anniversary celebration.[69] In 1999, she was also elected Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets, a post she held until 2005.[70] In 2003, she was appointed the final judge of the Yale Series of Younger Poets, a position she held until 2010. The Yale Series is the oldest annual literary competition in the United States, and during her time as judge, she selected for publication works by the poets Peter Streckfus and Fady Joudah, among others.[71]

Glück has been a visiting faculty member at many institutions, including Stanford University, Boston University, and the Iowa Writers Workshop.

Work

Glück's work has been, and continues to be, the subject of academic study. Her papers, including manuscripts, correspondence, and other materials, are housed at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University.[72]

Form

Glück is best known for lyric poems of linguistic precision and austere tone. The poet Craig Morgan Teicher has described her as a writer for whom "words are always scarce, hard won, and not to be wasted".[73] The scholar Laura Quinney has argued that her careful use of words has put Glück into "the line of American poets who value fierce lyric compression," from Emily Dickinson to Elizabeth Bishop.[74] Glück's poems rarely use rhyme, instead relying on repetition, enjambment, and other techniques to achieve rhythm.

Among scholars and reviewers, there has been discussion as to whether Glück is properly assessed as a confessional poet, owing to the prevalence of the first-person mode in her poems and their intimate subject matter, often inspired by events in Glück's personal life. The scholar Robert Baker has argued that Glück "is surely a confessional poet in some basic sense,"[75] while the critic Michael Robbins has argued that Glück's poetry, unlike that of confessional poets Sylvia Plath or John Berryman, "depends upon the fiction of privacy".[76] In other words, she cannot be a confessional poet, Robbins argues, if she does not address an audience. Going further, Quinney argues that, to Glück, the confessional poem is "odious".[74] Others have noted that Glück's poems can be viewed as autobiographical, while her technique of using mythology and inhabiting various personas renders her poems more than mere confessions. As the scholar Helen Vendler has noted: "In their obliquity and reserve, [Glück's poems] offer an alternative to first-person 'confession', while remaining indisputably personal".[77]

Themes

While Glück's work is thematically diverse, scholars and critics have identified several themes that are paramount. Most prominently, Glück's poetry can be said to be focused on trauma, as she has written throughout her career about death, loss, rejection, the failure of relationships, and attempts at healing and renewal. The scholar Daniel Morris notes that even a Glück poem that uses traditionally happy or idyllic imagery "suggests the author's awareness of mortality, of the loss of innocence".[17] The scholar Joanne Feit Diehl echoes this notion when she argues that "this 'sense of an ending'…infuses Glück's poems with their retrospective power," pointing to her transformation of common objects, such as a baby stroller, into representations of loneliness and loss.[78] Yet, for Glück, trauma is arguably a gateway to a greater appreciation of life, a concept perhaps most obviously explored in The Triumph of Achilles. The triumph to which the title alludes is Achilles' acceptance of mortality—which enables him to become a more fully realized human being.[79]

The relationship between the opposing forces of life and death in Glück's work points to another of her common themes: desire. Glück has often written explicitly about many forms of desire—for example, the desire for love and attention, for insight, or for the ability to convey truth—but her approach to desire is marked by ambivalence. Morris argues that Glück's poems, which often adopt contradictory points of view, reflect "her own ambivalent relationship to status, power, morality, gender, and, most of all, language".[80] The author Robert Boyer has characterized Glück's ambivalence toward desire as a result of "strenuous self-interrogation". He argues that "Glück's poems at their best have always moved between recoil and affirmation, sensuous immediacy and reflection…for a poet who can often seem earthbound and defiantly unillusioned, she has been powerfully responsive to the lure of the daily miracle and the sudden upsurge of overmastering emotion".[81] The tension between competing desires in Glück's work manifests both in her assumption of different personas from poem to poem and in her varied approach to each collection of her poems. This has led the poet and scholar James Longenbach to declare that "change is Louise Glück's highest value" and "if change is what she most craves, it is also what she most resists, what is most difficult for her, most hard-won".[82]

Another of Glück's poetic preoccupations is nature, the setting for many of her poems. Famously, in The Wild Iris, the poems take place in a garden where flowers have intelligent, emotive voices. However, Morris points out that The House on Marshland is also concerned with nature and can be read as a revision of the Romantic tradition of nature poetry.[83] In Ararat, too, "flowers become a language of mourning," useful for both commemoration and competition among mourners to determine the "ownership of nature as a meaningful system of symbolism".[84] Thus, in Glück's work nature is both something to be regarded critically and embraced. As the author and critic Alan Williamson has pointed out, it can also sometimes suggest the divine, as when, in the poem "Celestial Music," the speaker states that "when you love the world you hear celestial music," or when, in The Wild Iris, the deity speaks through changes in weather.[85]

Thematically, Glück's poetry is also notable for what it avoids. Morris argues that "Glück's writing most often evades ethnic identification, religious classification, or gendered affiliation. In fact, her poetry often negates critical assessments that affirm identity politics as criteria for literary evaluation. She resists canonization as a hyphenated poet (that is, as a "Jewish-American" poet, or a "feminist" poet, or a "nature" poet), preferring instead to retain an aura of iconoclasm, or in-betweenness".[86]

Influences

Glück has pointed to the influence of psychoanalysis on her work, as well as her early learning in ancient legends, parables, and mythology. In addition, she has credited the influence of Léonie Adams and Stanley Kunitz. Scholars and critics have pointed to the literary influence on her work of Robert Lowell,[87] Rainer Maria Rilke,[76] and Emily Dickinson,[88] among others.

Selected bibliography

Poetry collections

- Firstborn (The New American Library, 1968)

- The House on Marshland (The Ecco Press, 1975) ISBN 978-0912946184

- Descending Figure (The Ecco Press, 1980) ISBN 978-0912946719

- The Triumph of Achilles (The Ecco Press, 1985) ISBN 978-0880010818

- Ararat (The Ecco Press, 1990) ISBN 978-0880012478

- The Wild Iris (The Ecco Press, 1992) ISBN 978-0880012812

- The First Four Books of Poems (The Ecco Press, 1995) ISBN 978-0880014212

- Meadowlands (The Ecco Press, 1997) ISBN 978-0880014526

- Vita Nova (The Ecco Press, 1999) ISBN 978-0880016346

- The Seven Ages (The Ecco Press, 2001) ISBN 978-0060185268

- Averno (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2006) ISBN 978-0374107420

- A Village Life (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2009) ISBN 978-0374283742

- Poems: 1962-2012 (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2012) ISBN 978-0374126087

- Faithful and Virtuous Night (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2014) ISBN 978-0374152017

Chapbooks

- The Garden (Antaeus Editions, 1976)

- October (Sarabande Books, 2004) ISBN 978-1932511000

Prose collections

- Proofs and Theories: Essays on Poetry (The Ecco Press, 1994) ISBN 978-0880014427

- American Originality: Essays on Poetry (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2017) ISBN 978-0374299552

Further reading

- Burnside, John, The Music of Time: Poetry in the Twentieth Century, London: Profile Books, 2019.

- Dodd, Elizabeth, The Veiled Mirror and the Woman Poet: H.D., Louise Bogan, Elizabeth Bishop, and Louise Glück, Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1992.

- Doreski, William, The Modern Voice in American Poetry, Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1995.

- Feit Diehl, Joanne, editor, On Louise Glück: Change What You See, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2005.

- Gosmann, Uta, Poetic Memory: The Forgotten Self in Plath, Howe, Hinsey, and Glück, Madison: Farleigh Dickinson University Press, 2011.

- Morris, Daniel, The Poetry of Louise Glück: A Thematic Introduction, Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2006.

- Upton, Lee, The Muse of Abandonment: Origin, Identity, Mastery in Five American Poets, Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 1998.

- Vendler, Helen, Part of Nature, Part of Us: Modern American Poets, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980.

References

- ^ "Louise Glück | Authors | Macmillan". US Macmillan. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Morris, Daniel (2006). The Poetry of Louise Glück: A Thematic Introduction. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. pp. 25.

- ^ Glück, Louise (1994). Proofs & Theories: Essays on Poetry. New York: The Ecco Press. p. 5.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Weeks, Linton (29 August 2003). "Gluck to be Poet Laureate". The Washington Post. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ Glück, Louise. Proofs & Theories: Essays on Poetry. p. 7.

- ^ Glück, Louise. Proofs & Theories: Essays on Poetry. p. 8.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Glück, Louise. Proofs & Theories: Essays on Poetry. p. 11.

- ^ "Louise Glück Biography and Interview". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ Gluck, Louise (2012). ""A Voice of Spiritual Prophecy". Louise Gluck Interview. Academy of Achievement, Washington D.C., Oct 27, 2012". Academy of Achievement.

- ^ Glück, Louise. Proofs & Theories: Essays on Poetry. p. 13.

- ^ Morris, Daniel. The Poetry of Louise Glück: A Thematic Introduction. p. 28.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Haralson, Eric L. (2014-01-21). Encyclopedia of American Poetry: The Twentieth Century. Routledge. p. 252. ISBN 978-1-317-76322-2.

- ^ Chiasson, Dan (November 4, 2012). "The Body Artist". The New Yorker (November 12, 2012).

- ^ Jump up to:a b "Louise Glück". National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Morris, Daniel. The Poetry of Louise Glück: A Thematic Introduction. p. 29.

- ^ Duffy, John J.; Hand, Samuel B.; Orth, Ralph H. (2003). The Vermont Encyclopedia. UPNE. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-58465-086-7.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Morris, Daniel. The Poetry of Louise Glück: A Thematic Introduction. p. 4.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Flagg, Kathryn. "Vermont's Struggling Culinary School Plans Its Next Course". Seven Days Vermont. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ George, E. Laurie (1990). "The "Harsher Figure" of Descending Figure: Louise Gluck's "Dive into the Wreck"" (PDF). Women's Studies. 17: 235–247. doi:10.1080/00497878.1990.9978808.

- ^ Rosenberg, Liz (1985-12-22). "Geckos, Porch Lights and Sighing Gardens". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ Stitt, Peter (1985). "Contemporary American Poems: Exclusive and Inclusive". The Georgia Review. 39 (4): 849–863. ISSN 0016-8386. JSTOR 41398888.

- ^ Abel, Colleen (2019-01-15). "Speaking Against Silence". The Ploughshares Blog. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ Hahn, Robert (Summer 2004). "Transporting the Wine of Tone: Louise Gluck in Italian". Michigan Quarterly Review. XLIII (3). hdl:2027/spo.act2080.0043.313. ISSN 1558-7266.

- ^ Williams College. "Poet Louise Glück at Williams College Awarded Coveted Bollingen Prize". Office of Communications. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "A zest for life: Beatrice Glück of Woodmere dies at 101". Herald Community Newspapers. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ Garner, Dwight (2012-11-08). "Verses Wielded Like a Razor". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Wild Iris". Publishers Weekly. 29 June 1992. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Images of Now and Then in Poetry's Mirror". Christian Science Monitor. 1993-01-07. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ Azcuy, Mary Kate (2011), "Persona, Trauma and Survival in Louise Glück's Postmodern, Mythic, Twenty-First-Century 'October'", Crisis and Contemporary Poetry, Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 33–49, doi:10.1057/9780230306097_3, ISBN 978-0-230-30609-7

- ^ Speirs, Stephanie (9 November 2004). "Gluck waxes poetic on work". yaledailynews.com. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Creative Paralysis". The American Scholar. 2013-12-06. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "John Theodore Dranow 1948-2019". legacy.com. 14 November 2019.

- ^ "Obituary: Gluck, Tereze". legacy.com. 19 December 2018.

- ^ "Literature Fellowships list". NEA. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "John Simon Guggenheim Foundation | Louise Glück". Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Awards – American Academy of Arts and Letters". Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ Williams College. "Honorary Degrees". Commencement. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Louise Elisabeth Gluck". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Vermont - State Poet Laureate (State Poets Laureate of the United States, Main Reading Room, Library of Congress)". www.loc.gov. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "July 29, 1998". Middlebury. 2010-10-11. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Academy Members – American Academy of Arts and Letters". Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Lannan Foundation". Lannan Foundation. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Soundings: Spring 01". web.mit.edu. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Louise Gluck | The Bollingen Prize for Poetry". bollingen.yale.edu. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Louise Glück: Online Resources - Library of Congress Bibliographies, Research Guides,and Finding Aids (Virtual Programs & Services, Library of Congress)". www.loc.gov. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ Poets, Academy of American. "Wallace Stevens Award | Academy of American Poets". poets.org. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Aiken Taylor Award". The Sewanee Review. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Search Results for "Gluck" – American Academy of Arts and Letters". Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Louise Glück". National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ Berggren, Jenny (2020-02-14). "Poeten Louise Glück får Tranströmerpriset 2020". SVT Nyheter(in Swedish). Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Eberhart and Ginsberg Win Frost Poetry Medal". The New York Times. 1986-04-17. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ Jump up to:a b "All Past National Book Critics Circle Award Winners and Finalists – National Book Critics Circle". www.bookcritics.org. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Rebekah Johnson Bobbitt National Prize for Poetry (Prizes and Fellowships, The Poetry and Literature Center at the Library of Congress)". www.loc.gov. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Pulitzer Prize Winners by Year: 1993". www.pulitzer.org. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "PEN/Martha Albrand Award for First Nonfiction Winners". PEN America. 2016-05-05. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "ESU Programs - Books Across The Sea". 2008-08-20. Archived from the original on 2008-08-20. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "English Speaking Union of the United States". 2008-08-20. Archived from the original on 2008-08-20. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "PEN New England and the JFK Presidential Library Announce Winners of the 2007 Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award and the 2007 L.L. Winship/PEN New England Awards | JFK Library". www.jfklibrary.org. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ LA Times Festival of Books. "List of Honorees". Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "National Book Awards 2014". National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Louise Glück". National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Louise Gluck". www.pulitzer.org. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ Says, Tarsitano. "Griffin Poetry Prize: Louise Glück". Griffin Poetry Prize. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Table of Contents: Norton Anthology of Poetry". library.villanova.edu. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "Table of contents for The Oxford book of American poetry". catdir.loc.gov. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ Parini, Jay, ed. (1995). The Columbia Anthology of American Poetry. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-08122-1.

- ^ "Librarian of Congress Makes Unprecedented Poetry Appointments". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Louise Glück | Steven Barclay Agency". www.barclayagency.com. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "The Judges". Yale Series of Younger Poets. 2014-02-26. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Collection: Louise Glück papers | Archives at Yale". archives.yale.edu. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ Teicher, Craig Morgan (2017-08-04). "Deep Dives Into How Poetry Works (and Why You Should Care)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Quinney, Laura (2005-07-21). "Laura Quinney · Like Dolls with Their Heads Cut Off: Louise Glück · LRB 21 July 2005". London Review of Books. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ Baker, Robert (2018-06-01). "Versions of Ascesis in Louise Glück's Poetry". The Cambridge Quarterly. 47 (2): 131–154. doi:10.1093/camqtly/bfy011. ISSN 0008-199X.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Robbins, Michael. "The Constant Gardener: On Louise Glück". Los Angeles Review of Books. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ Vendler, Helen (1980). Part of Nature, Part of Us: Modern American Poets. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 311. ISBN 9780674654761.

- ^ Diehl, Joanne Feit, ed. (2005). On Louise Glück: Change What You See. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. pp. 6–7. ISBN 0472114794.

- ^ ""The Ambivalence of Being in Gluck's The Triumph of Achilles" [by Caroline Malone]". The Best American Poetry. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ Morris, Daniel. The Poetry of Louise Glück: A Thematic Introduction. p. 73.

- ^ Boyers, Robert (2012-11-20). "Writing Without a Mattress: On Louise Glück". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ LONGENBACH, JAMES (1999). "Louise Glück's Nine Lives". Southwest Review. 84 (2): 184–198. ISSN 0038-4712. JSTOR 43472558.

- ^ Morris, Daniel. The Poetry of Louise Glück: A Thematic Introduction. p. 2.

- ^ Morris, Daniel. The Poetry of Louise Glück: A Thematic Introduction. p. 6.

- ^ Williamson, Alan (2005). "Splendor and Mistrust". In Diehl, Joanne Feit (ed.). On Louise Glück: Change What You See. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. pp. 65–66.

- ^ Morris, Daniel. The Poetry of Louise Glück: A Thematic Introduction. pp. 30–31.

- ^ Gargaillo, Florian (2017-09-29). "Sounding Lowell: Louise Glück and Derek Walcott". Literary Matters. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ Diehl, Joanne Feit (2005). "Introduction". In Diehl, Joanne Feit (ed.). On Louise Glück: Change What You See. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. pp. 13, 20.

External links[edit]

- Full text of Averno available at The Floating Library

- [https://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/gluck/ Louise Glück: Online Resources from the Library of Congress

- Louise Glück Biography and Interview on American Academy of Achievement

- Yale University English Department Profile of Glück

- Boston University Creative Writing Department Profile of Glück

- Louise Glück at poets.org

- Louise Glück: Online Resources from Modern American Poetry, Department of English, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- Louise Glück In Conversation

- Griffin Poetry Prize biography

- Griffin Poetry Prize reading, including video clip

- Louise Glück — Can I Only Love That I Conceive?

- Louise Glück Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.