布罗茨基 | 献给约翰•邓恩的哀歌(王家新 译)

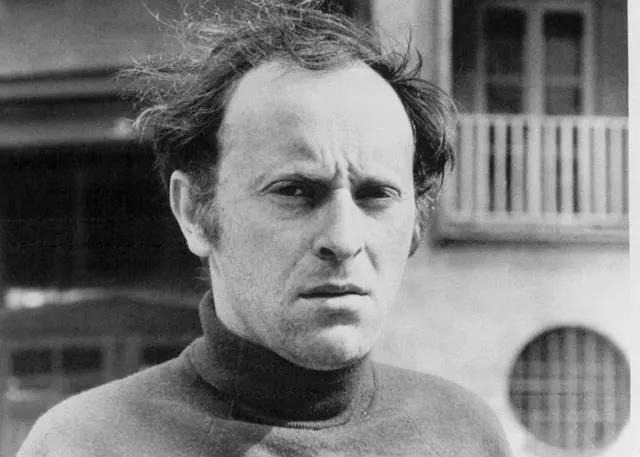

约瑟夫•布罗茨基(Joseph Brodsky,1940-1996),俄裔美国诗人,散文家。1940年5月24日生于苏联列宁格勒,1955年开始创作诗歌,1972年被剥夺苏联国籍,驱逐出境,后移居美国,曾任密歇根大学驻校诗人,后在其他大学任访问教授,1977年加入美国籍。代表作品有诗集《诗选》《致乌拉尼亚》,散文集《小于一》《悲伤与理智》等。 1987年,由于其作品“超越时空限制,无论在文学上及敏感问题方面,都充分显示出他广阔的思想和浓郁的诗意”,布罗茨基荣获诺贝尔文学奖,此时他47岁,是有史以来最年轻的诺贝尔文学奖得主。

约翰•邓恩(John Donne,1572-1631)是十七世纪英国玄学派诗人、教士,他对现代诗歌产生了深刻的影响。1963年,布罗茨基发表著名长诗《献给约翰•邓恩的哀歌》,这也是他早期创作的代表作品。今天小雅与大家分享王家新老师翻译的这首诗作。

献给约翰•邓恩的哀歌

约翰•邓恩坠入了睡眠……他周围的一切

也睡了:墙,床,和地板——都睡了。

桌子,画像,地毯,挂钩和门闩,

衣柜,碗橱,烛火,窗帘——一切

都睡了:水罐,瓶子,玻璃杯,面包,

面包刀,瓷具,水晶器皿,陶盆和平底锅,

亚麻桌布,灯罩,座钟,拉出的抽屉,

镜子,楼道,门槛。夜无处不在。

夜,到处都是:在角落处,在眼瞳里,

在桌布上,在桌上的纸页间,在磨损的词语

和褪色的言辞里,在圆木和火钳间,

在壁炉变暗的炭块上——在每一样物体里。

在汗衫上,靴子里,袜子上,在阴影中,

在镜子背后,椅子背后,

在床铺上和脸盆上,在十字架上,

在枕头上,在拖鞋里,在门口的

扫帚上。一切都沉入了睡眠。

是的,一切都睡了。窗户。窗外的雪。

一面屋顶的斜坡,比桌布更白,陡峭的

屋脊。邻居的房舍在积雪中,

被锋利的窗框一一镌刻。

拱顶和墙壁和窗户——一切都睡了。

木头亭子栅栏,鹅卵石,花园,烧烤架。

没有光亮闪动,没有车轮的吱嘎……

铁链,围墙,雕饰,走道镶边。

房子门环,门把手,挂钩,

门铃,门槛,门闩和机灵的钥匙。

听不到任何低语声、簌簌声和震动。

只有雪的挤压声。所有人在沉睡。

天亮还早。所有的监狱和闸门

也睡了。鱼铺里的铁秤在睡。

煮过的猪肉在睡。后院

和房子。带铁链的看门狗睡在寒冷里。

地窖里的猫竖着耳朵在睡。

老鼠在睡,人类在睡。伦敦在酣睡。

船帆向着铁锚打瞌睡。咸涩的海水

在船体下边与落雪梦呓般交谈,

边融入远处熟睡的天穹。

约翰•邓恩睡了,海与他一起睡了。

白垩崖塔一样安睡在海滩之上。

整个岛在睡,被孤寂的梦拥住。

每个院落都有三道栅门。

槭树,松树,云杉,冷杉——都睡了。

山坡的石阶和山间的溪流与小径

现在也睡了。狐狸和狼群。熊在洞穴里。

雪高高地堆积在洞口。

所有的鸟儿在睡。它们的鸣叫

和乌鸦的嘎嘎声都不再听到。这是夜,

猫头鹰空洞的笑也静了下来。

英国的乡村沉静。星星闪烁,

老鼠在悔过。所有的造物都睡了。

死者静静地躺在坟墓里或梦里,

活着的,睡在他们长袍的海洋中。

每个人都孤单地躺在床上。或搂着

另一个。山坡,树林,河流,所有的

鸟兽都睡了。所有活着的和死去的。

只有雪在夜空中飞舞着白色。

那里,在人类的头顶,一切也睡了。

天使们在睡。圣徒们,怀着神圣的羞愧,

已淡忘了我们这个苦恼的尘世。

愤怒的地狱之火在睡,天堂的荣耀也在睡。

无人在这昏暗的时辰出门。

甚至上帝也入睡了。大地显得陌生。

眼睛不再看,耳朵忍受无声。

恶魔在睡。疯狂的敌意与他一同

坠入睡眠,在英格兰白雪覆盖的乡野。

骑士们在睡。天使长手持号角

也在睡。马在梦里轻微晃动。

所有的小天使挤成一团,被拥抱着,

在圣保罗大教堂的穹顶下安睡。

约翰•邓恩入睡了。他的诗也睡了。

他的意象,韵脚,他的松驰了的

强有力节奏。焦虑和罪孽,

相呼相继,都在他的音节里安歇。

每一行诗都在对下一行亲人般低语:

“朝前挪动挪动”。但是每一行

都距天国大门如此遥远,如此可怜,

纯净,稠密,看上去都一样。

所有的诗行在熟睡,抑扬格的

严谨穹顶在升腾中入睡。扬抑格

东倒西歪,像打盹的卫兵。

忘川之水的幻影在沉睡。

诗人的名声也在它自身里酣睡。

所有的折磨和苦难都沉入睡眠。

恶习在睡。善睡在恶的臂弯里。

先知们在睡。漂白的雪穿过

无尽空间,寻找那最后的未覆盖处。

一切都陷在睡眠里。一排排的书,

词语的湍流,覆盖在遗忘的冰层里。

所有的言说在睡,它们言说的真理

也在睡。链接的链条在睡,几乎不再作响。

一切都在睡:圣徒,恶魔,上帝。

他们的凶恶仆人。孩童。友朋。只有雪

在昏暗的路上飞撒和嘶嘶作响——

这个世界上再无其他别的声音。

但是请听!难道你没有听见这寒夜里

哽咽的声音,恐惧的低语声吗?

那儿有人暴露在严冬的气流中

并在哭泣。那个人站在稠密的昏暗里。

他的声音细小,细小得像一枚

没有穿上线的针……他孤身一人

浮游、穿越在雪中——拖着寒雾的斗篷——

将黑夜缝向黎明,那高悬的黎明。

“这是谁在哭泣?我的天使,是你吗?

是你隐现在雪中等候,孤独地

等着我的到来?是你在阴郁的家中徘徊,

无爱,而在黑暗中呼喊?”

没有回答。“是你吗?哦小天使,你的泪

又把我置于那悲痛的合唱。你是否

已决意要离开这沉睡的教堂?是吗?”

没有回答。“是你吗,保罗?你的声音

巳被严酷的话语磨得如此粗糙。

难道不是你垂着已灰白的头

在黑暗里哭泣?”寂静,没有回应。

“难道不是那只护住我迟钝眼睛的手——

在任何时候——又在那里隐现?

难道那不是你吗,主?哦不,我简直疯了。

可在那高处确有一个声音在哭泣。”

没有回应。寂静。“是你吗,加百利,

难道不是你对咆哮的猎犬吹响了号角?

然而只有我在睁眼站着,当骑士们

把马鞍配上他们的坐骑?是的,

一切仍在沉睡。浓雾迷漫。天国的猎犬

成群逃散。哦加百利,难道不是你

手持号角,在这严冬的围困里哭泣?”

“不,这是我,约翰•邓恩,你的灵魂。

是我在这天国的高处独自悲伤,

因为我的劳作给生命展现出

铁链般沉重的感情和思想。

带着这重负,你才能攀援并高飞在

所有的罪孽与激情之上。

你曾是一只鸟,到处可见你的人民,

当你从他们屋顶的斜坡上飞过。

你瞥见过所有大海,所有遥远的陆地。

你目睹过地狱——先是在你的梦里,

然后它到处醒来。你也见过珍宝般的天堂,

镶嵌在人类悲惨欲求的框架里。

你看见生命:你的孪生岛屿。

你从它的岸边看向海洋。咆哮的黑暗

从每一只手掌上涌来。

你飞着越过上帝,然后又跌落回来,

这重负不会让你飞向那高处,从那里

这泡沫般的世界不过是几座高塔

和几条河流的缎带,到了那里,

对低身俯瞰的他来说

可怕的最后审判似乎也不再可怕。

在那个国度里,光照不会褪色。

从那里看,这里只是一个微弱发热的梦。

从那里,我们的主是从雾中、从最遥远

房屋的窗口透出的光。

但是田野如此荒凉,犁沟未被翻起,

岁月未被耕种,整整一个世纪。

森林站立,如坚固的墙。

倾盆大雨击打着满是泪光的草叶。

第一个伐木者——那骑着一匹瘦马的他,

在丛林的惊慌恐惧中,跌跌撞撞地

爬上松树,看见了一道突然冒起的

烽烟,在他自己远方的山谷里。

一切都很遥远。昏暗在移近。

闪亮的水平线在远处的屋脊上升落。

这里一切明亮。没有猎犬的吠叫

或激荡在沉默空气里的钟声。

而,当他明白一切都很遥远,

他调头策马驶回了森林。

即刻间,缰绳,雪橇,夜,他可怜的坐骑,

他自己——都融入一个圣书的梦境。

“但是,这里我站立和哭泣。无路可走。

我注定要活在这些墓碑中间。

我怎能以我的肉身飞起;

如此的飞翔对我只能通过死亡,

在潮湿的大地上,当我忘了你——

我的世界,一次性地,永久地忘记。

我将追随,在欲望的痛苦折磨中,

以我的肉体来缝补这最后的分离。

但是请听!当我在这里用哭泣

惊动你的安睡,匆忙的飞雪穿越黑暗,

它没有融化,在缝补着破损——

它的针线在穿梭,在前后翻飞!

这不是我在哭泣,约翰•邓恩,是你:

你孤独地躺着。你的锅碗在橱柜里安睡,

当漂流的雪堆靠近你沉睡的房子,

当筛落的雪片从天国向地面飞去。”

如同一只鸟,他睡在自己的巢穴里,

他的纯粹道路、对更高生命的渴望,

还有他自己都托付给了那颗坚定的星,

此刻它被乌云遮掩。如同一只鸟,

他的灵魂纯净,他在大地上的生命

虽然需要有一阵风来涤清,但仍然

比高筑在欧椋鸟空巢之上的

乌鸦的窝穴更接近天意。

如同一只鸟,他将在黎明醒来。

但此刻他仍在白色床单下躺着,

当飞雪和睡眠在他的灵魂和梦着的

肉体之间缝补着悸动的空隙。

一切都睡着了,但那首最后的诗

在等待完成,它龇牙咧嘴,

声称尘世之爱只是诗人的责任,

而神圣的爱才合乎一个教长的意欲。

无论磨坊怎样转动水流,在这人世上,

它都碾磨着同样粗糙的谷粒。

纵使我们的生命可以与人分享,

又有谁和我们分享死亡?

人的衣物露出了破绽,如果他来撕扯,

可以从这边或那边。

它成了碎片,但它又全然完整。

再一次它绽裂。只有上苍

会在昏暗中带着复原的针线缝补。

睡吧,约翰•邓恩,睡吧。好好睡,别再折磨

你的灵魂。外套破了,所有的紊乱

悬挂在那里。但是看,有颗星在云层里闪亮,

正是它使你的世界一直忍受到现在。

2018年1月9-15日,译于北京

“不,这是我,约翰•邓恩,你的灵魂”

——布罗茨基《献给约翰•邓恩的哀歌》译后记

翻译这首伟大的挽歌,于我首先是出于“回报”。我们都曾受到过布罗茨基的影响。因此,我对这首挽歌的翻译,如按本雅明在《译者的使命》中的说法,完全是出自对“生命”的“不能忘怀”。当然,就翻译本身而言,也是出自语言本身的“未能满足的要求”。

至于一位俄国年轻诗人(布罗茨基是在23岁时写下这首诗的!)为什么会向一位十七世纪英国诗人献上他的挽歌,这里简单介绍一下:布罗茨基生性叛逆,早年从高中退学以后边打工边写诗,并自学波兰语和英语,翻译了米沃什、约翰•邓恩等波兰语和英语诗人。后来在一次访谈中他曾谈到邓恩对他的影响,说他从邓恩那里学到了诗歌的结构和陌生化技巧,学到了观察生活和世界时所采取的态度,等等。这些,我们都可以在这首挽歌中感到。而在翻译这首诗时,我还不时想起了约翰•邓恩的一句名言:“全体人类就是一本书。当一个人死亡,这并非有一章被从书中撕去,而是被翻译成一种更好的语言。”布罗茨基就是一位对生与死、对存在与虚无进行“翻译”的非凡诗人!据他的早年诗友耐曼回忆,临近1962年,布罗茨基“开始用自己的声音讲话”(这一年他写出了他的惊人之作《黑马》),1963年,他完成了这首约翰•邓恩挽歌,而到了1965年,他们拜以为师的阿赫玛托娃“就知道他是一个大师级的诗人,而我们都不知晓。”的确,任何有着诗的敏感的读者读了这首挽歌,就会感到“一个大师级的诗人”出现在他们面前。“最主要的事情是构思的宏伟”(布罗茨基)。而这也正是这首挽歌给人的印象。我们也不能不为诗中所展现的非凡构思、想象力、精神视野和诗歌技艺所折服。首先是他非常大胆地刻划了一长串几乎无穷无尽的物体的“睡”(这让我联想到洛尔迦的那首《伊•桑•梅希亚斯挽歌》,它的第一章也很惊人,一连串穿插了近三十个“在下午五点钟”)。奥登当年在为布罗茨基英译诗选作序时,就曾特意提到这一点。而这,不单是写法上的大胆,这出自一首悲痛挽歌的內在要求。正如有人指出的那样:“随着列举的物件在增加,随着诗行在增多,形成了一种內部的力量,所描写的范围很自然地扩大开来,从房间和近处,扩展到全世界”。(《二十世纪俄罗斯文学史:20-90年代主要作家》,谢•伊•科尔米洛夫主编,赵丹等译,南京大学出版社,2017)这就是说,这首挽歌不仅是献给一位诗人的,也是宇宙性的。它不仅气象非凡,包容了宏伟而深远的悲伤音乐,也充满了为我们一时难以穷尽的精神內涵。而我的翻译,不仅要使中国读者从诗人那里获得一种非凡的视野,也要使他们能够真切地“听出”这首诗,小至一些细节,如“听不到任何低语声、簌簌声和震动。/只有雪的挤压声”(这来自一首诗内部的“挤压声”!),高至寒夜苍穹里那“哽咽的声音”,或者说,要最终使他们从自己的生命中也发出这样的回应:“不,这是我,约翰•邓恩,你的灵魂”——也只有这样,我们才能来到一部伟大作品的面前。我的翻译依据的是克莱恩的英译本。克莱恩是布罗茨基诗歌最早的译者之一,1973年就出版了布罗茨基诗选(__Select__ed poems,Joseph Brodsky;translated and introducedby George L. Kline ,with a foreword by W.H.Auden. Penguin),奥登在序言中就极大地肯定了他的翻译:“我不懂俄语,因此被迫将我的判断建立在英语译文上。我认为克莱恩教授的翻译公正地对待了原作,其主要理由是它们使我相信约瑟夫•布罗茨基是个优秀的手艺人。”在该序文的最后奥登又说:“读了克莱恩教授的翻译之后,我毫不犹豫地表明,在俄语里,约瑟夫•布罗茨基一定是个一流的诗人,一个祖国应该为他而骄傲的人,我对他们两个都很感谢。”克莱恩译本是我目前看到的唯一英译本,当然,我希望还有其他译本。如按本雅明的说法,伟大的作品一经诞生,它的译文或者说它的“来世”已在那里了。而我们的翻译,无非是再次听到并响应了这种生命的召唤。

Elegyfor John Donne

John Donne has sunk in sleep...All things beside

are sleeping too: walls, bed, and floor-all sleep.

The table, pictures, carpets, hooks and bolts,

clothes-clo__set__s, cupboards, candles, curtains-all

now sleep: the washbowl, bottle, tumbler, bread,

breadknife and china, crystal, pots and pans,

fresh linen, nightlamp, chests of drawers, a clock,

a mirror, stairway, doors. Night everywhere,

night in all things: in corners, in men's eyes,

in linen, in the papers on a desk,

in the wormed words of stale and sterile speech,

in logs and fire-tongs, in the blackened coals

of a dead fireplace-in each thing.

In undershirts, boots, stockings, shadows, shades,

behind the mirror, on the backs of chairs,

in bed and washbowl, on the crucifix,

in linen, in the broom beside the door,

in slippers. All these things have sunk in sleep.

Yes, all things sleep. The window. Snow beyond.

A roof-slope, whiter than a tablecloth,

the roof's high ridge. A neighborhood in snow,

carved to the quick by this sharp windowframe.

Arches and walls and windows-all asleep.

Wood paving-blocks, stone cobbles, gardens, grills.

No light will flare, no turning wheel will creak. . .

Chains, walled enclosures, ornaments, and curbs.

Doors with their rings, knobs, hooks are all asleep-

their locks and bars, their bolts and cunning keys.

One hears no whisper, rustle, thump, or thud.

Only the snow creaks. All men sleep. Dawn comes

not soon. All jails and locks have lapsed in sleep.

The iron weights in the fish-shop are asleep.

The carcasses of pigs sleep too. Backyards

and houses. Watch-dogs in their chains lie cold.

In cellars sleeping cats hold up their ears.

Mice sleep, and men. And London soundly sleeps.

A schooner nods at anchor. The salt sea

talks in its sleep with snows beneath her hull,

and melts into the distant sleeping sky.

John Donne has sunk in sleep, with him the sea.

Chalk cliffs now tower in sleep above the sand.

This Island sleeps, embraced by lonely dreams,

and every garden now is triple-barred.

The maples, pines, spruce, silver firs-all sleep.

On mountain slopes steep mountain-streams and paths

now sleep. Foxes and wolves. Bears in their dens.

The snowy drifts high at burrow-entrances.

All the birds sleep. Their songs are heard no more.

Nor is the crow's hoarse caw. 'Tis night. The owl's

dark, hollow laugh is silenced now.

The English countryside is still. Stars flame.

The mice are penitent. All creatures sleep.

The dead lie calmly in their graves and dream.

The living, in the oceans of their gowns,

sleep-each alone-within their beds. Or two

by two. Hills, woods, and rivers sleep. All birds

and beasts now sleep-nature alive and dead.

But still the snow spins white from the black sky.

There, high above men's heads, all are asleep.

The angels sleep. Saints-to their saintly shame-

have quite forgotten this our anxious world.

Dark Hell-fires sleep, and glorious Paradise.

No one goes forth from home at this bleak hour.

Even God has gone to sleep. Earth is estranged.

Eyes do not see, and ears perceive no sound.

The Devil sleeps. Harsh enmity has fallen

asleep with him on snowy English fields.

All horsemen sleep. And the Archangel, with

his trumpet. Horses, softly swaying, sleep.

And all the cherubim, in one great host

embracing, doze beneath St. Paul's high dome.

John Donne has sunk in sleep. His verses sleep.

His images, his rhymes, and his strong lines

fade out of view. Anxiety and sin,

alike grown slack, rest in his syllables.

And each verse whispers to its next of kin,

"Move on a bit." But each stands so remote

from Heaven's Gates, so poor, so pure and dense,

that all seem one. All are asleep. The vault

austere of iambs soars in sleep. Like guards,

the trochees stand and nod to left and right.

The vision of Lethean waters sleeps.

The poet's fame sleeps soundly at its side.

All trials, all sufferings, are sunk in sleep.

And vices sleep. Good lies in Evil's arms.

The prophets sleep. The bleaching snow seeks out,

through endless space, the last unwhitened spot.

All things have lapsed in sleep. The swarms of books,

the streams of words, cloaked in oblivion's ice,

sleep soundly. Every speech, each speech's truth,

is sleeping. Linked chains, sleeping, scarcely clank.

All soundly sleep: the saints, the Devil, God.

Their wicked servants. Children. Friends. The snow

alone sifts, rustling, on the darkened roads.

And there are no more sounds in the whole world.

But hark! Do you not hear in the chill night

a sound of sobs, the whispered voice of fear?

There someone stands, disclosed to winter's blast,

and weeps. There someone stands in the dense gloom.

His voice is thin. His voice is needle-thin,

yet without thread. And he in solitude

swims through the falling snow-cloaked in cold mist-

that stitches night to dawn. The lofty dawn.

"Whose sobs are those? My angel, is it thou?

Dost thou await my coming, there alone

beneath the snow? Dost walk-without my love-

in darkness home? Dost thou cry in the gloom?”

No answer.-“Is it you, oh cherubim,

whose muted tears put me in mind

of some sepulchral choir? Have you resolved

to quit my sleeping church? Is it not you?"

No answer.-“Is it thou, oh Paul? Thy voice

most certainly is coarsened by stern speech.

Hast thou not bowed thy grey head in the gloom

to weep?" But only silence makes reply.

“Has not that Hand protected my dull eyes,

that Hand which looms up here and in all times?

Is it not thou, Lord? No, my thought runs wild.

And yet how lofty is the voice that weeps.”

No answer. Silence.-“Gabriel, hast thou

not blown thy trumpet to the roar of hounds?

But did I stand alone with open eyes

while horsemen saddled their swift steeds? Yet each

thing sleeps. Enveloped in huge gloom, the hounds

of Heaven race in packs. Oh Gabriel,

dost thou not sob, encompasséd about

by winter dark, alone, with thy great horn?"

“No, it is I, thy soul, John Donne, who speaks.

I grieve alone upon the heights of Heaven,

because my labors did bring forth to life

feelings and thoughts as heavy as stark chains.

Bearing this burden, thou couldst yet fly up

past those dark sins and passions, mounting higher.

Thou wast a bird, thy people didst thou see

in every place, as thou didst soar above

their sloping roofs. And thou didst glimpse the seas,

and distant lands, and Hell-first in thy dreams,

then waking. Thou didst see a jewelled Heaven

__set__ in the wretched frame of men's low lusts.

Thou sawest Life: thine Island was its twin.

And thou didst face the ocean at its shores.

The howling dark stood close at every hand.

And thou didst soar past God, and then __drop__ back,

for this harsh burden would not let thee rise

to that high vantage point from which this world

seems naught but ribboned rivers and tall towers-

that point from which, to him who downward stares,

this dread Last Judgment seems no longer dread.

The radiance of that Country does not fade.

From thence all here seems a faint, fevered dream.

From thence our Lord is but a light that gleams,

through fog, in window of the farthest house.

The fields lie fallow, furrowed by no plow.

The years lie fallow, and the centuries.

Forests alone stand, like a steady wall.

Enormous rains batter the dripping grass.

The first woodcutter-he whose withered steed,

in panic fear of thickets, blundered thence-

will mount a pine to catch a sudden glimpse

of fires in his own valley, far away.

All things are distant. What is near is dim.

The level glance slides from a roof remote.

All here is bright. No din of baying hound

or tolling bell disturbs the silent air.

And, sensing that all things are far away,

he'll wheel his horse back quickly toward the woods.

And instantly, reins, sledge, night, his poor steed,

himself-will melt into a Scriptural dream.

"But here I stand and weep. The road is gone.

I am condemned to live among these stones.

I cannot fly up in my body's flesh;

such flight at best will come to me through death

in the wet earth, when I've forgotten thee,

my world, forgotten thee once and for all.

I'll follow, in the torment of desire,

to stitch up this last parting with my flesh.

But hark! While here with weeping I disturb

thy rest, the busy snow whirls through the dark,

not melting, as it stitches up this hurt-

its needles flying back and forth, back, forth!

It is not I who sob. 'Tis thou, John Donne:

thou liest alone. Thy pans in cupboards sleep,

while snow builds drifts upon thy sleeping house-

while snow sifts down to earth from highest Heaven."

Like a wild bird, he sleeps in his cold nest,

his pure path and his thirst for purer life,

himself entrusting to that steady star

which now is closed in clouds. Like a wild bird,

his soul is pure, and his life's path on earth,

although it needs must wind through sin, is still

closer to nature than that tall crow's nest

which soars above the starlings' empty homes.

Like a wild bird, he too will wake at dawn;

but now he lies beneath a veil of white,

while snow and sleep stitch up the throbbing void

between his soul and his own dreaming flesh.

All things have sunk in sleep. But one last verse

awaits its end, baring its fangs to snarl

that earthly love is but a poet's duty,

while love celestial is an abbot's flesh.

Whatever millstone these swift waters turn

will grind the same coarse grain in this one world.

For though our life may be a thing to share,

who is there in this world to share our death?

Man's garment gapes with holes. It can be torn

by him who will, at this edge or at that.

It falls to shreds, and is made whole again.

Once more 'tis rent. And only the far sky,

in darkness, brings the healing needle home.

Sleep, John Donne, sleep. Sleep soundly, do not fret

thy soul. As for thy coat, 'tis torn; all limp

it hangs. But see, there from the clouds will shine

that star which made thy world endure till now.

图源自网络

中国当代诗人,中国人民大学文学院教授,博士生导师。著有诗集、诗论随笔集、译诗集三十多种,另有中外现当代诗歌、诗论集编著数十种,其创作、诗学随笔、诗歌翻译均产生广泛影响,作品被译成多种文字发表和出版。曾获多种国内外文学奖、诗学批评奖、翻译奖和荣誉称号,其中包括2013年韩国KC国际诗文学奖、2017年“书业年度评选•翻译奖”、2018年第三届“李杜诗歌奖•成就奖”、2018年美国文学翻译协会卢西安•斯特里克亚洲文学翻译奖入围、2019年海峡两岸诗会“桂冠诗人”称号、2020年