邁剋爾·翁達傑的詩集

洞見詩刊 5/19

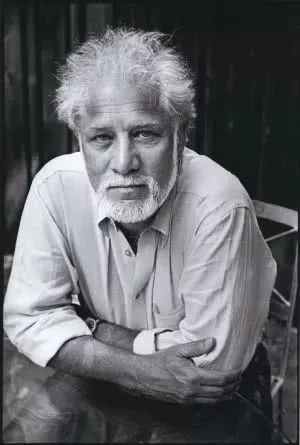

邁剋爾·翁達傑( Michael Ondaatje,1943-)是一位以詩聞名的加拿大作傢,但使他躋身國際知名作傢行列的,還是那部獲得布剋奬的富有如夢如幻般魅力的小說《英國病人》。

□□□.mp3

From 洞見詩刊

00:0004:23

邁剋爾·翁達傑詩集

聲音的誕生

夜裏,大狗拉長身子發出最私密的嗚嗚聲。

伸展最後的懶腰

躺在屋外幽黑的過道裏。

孩子們翻了翻身子。

一扇窗想要隔絶冰冷

另一隻狗在地毯上扒拉着抓虱子。

我們都很孤單。

(金雯 譯)

夜間的格裏芬

我的雙臂抱緊兒子

噩夢後汗濕

一個小我

嘴裏含着手指

另一隻手在我頭髮裏握緊

一個小我

噩夢後汗濕

(金雯 譯)

駕照申請

兩衹鳥的愛情

是一團紅色烈羽

綻開的棉球,

我從它們身邊駛過,它們沒有中斷。

我是個好司機,看什麽都無動於衷。

(金雯 譯)

Application For A Driving License

Two birds loved

in a flurry of red feathers

like a burst cottonball,

continuing while I drove over them.

I am a good driver, nothing shocks me.

疤痕周邊的時間

曾有一個女孩,和我幾年沒有聯繫

沒在一起喝咖啡

就疤痕寫了一段話。

疤痕躺在她的手腕上,光滑潔白,

吸血蟲的大小。

那是我的傑作

出自我揮動的一枚嶄新的意大利小刀。

聽着,我邊說邊轉身,

鮮血噴涌而出落在裙裾上。

我妻子的疤痕如水滴

散落於膝蓋和腳腕,

她和我提起破碎的暖房玻璃

我能做的衹是想象鮮紅的腳

(好比夏卡爾畫筆下的一個樹妖),

腦海裏撐不起這個場景。

我們總能回憶起疤痕周邊的時間,

它們封存無關的情感

把我們從眼前的朋友這裏拖走。

我記得這個女孩的臉,

漫開而上升的驚奇。

這道傷痕

當她與愛人或丈夫協動的時候

是會掩蓋還是炫耀,

抑或是收藏於玉腕,

當作神秘的時鐘。

而在我的回憶裏

它是一枚紀念無情的徽章。

我現在就願意和你見面

也希望那道傷痕

當初是與愛一起

來到你手上

衹是愛,與你我的緣分無關。

(金雯 譯)

The Time Around Scars

A girl whom I've not spoken to

or shared coffee with for several years

writes of an old scar.

On her wrist it sleeps, smooth and white,

the size of a leech.

I gave it to her

brandishing a new Italian penknife.

Look, I said turning,

and blood spat onto her shirt.

My wife has scars like spread raindrops

on knees and ankles,

she talks of broken greenhouse panes

and yet, apart from imagining red feet,

(a nymph out of Chagall)

I bring little to that scene.

We remember the time around scars,

they freeze irrelevant emotions

and divide us from present friends.

I remember this girl's face,

the widening rise of surprise.

And would she

moving with lover or husband

conceal or flaunt it,

or keep it at her wrist

a mysterious watch.

And this scar I then remember

is a medallion of no emotion.

I would meet you now

and I would wish this scar

to have been given with

all the love

that never occurred between us.

拿來

這是一種形式上的需要

對待我們欣賞的人

要把花骨朵從他們肉體中吮吸出來

再偷偷種在自己的頭顱裏

在孤獨的花園裏催生果實。

學着傾瀉鋼鐵般精準的

麯綫,柔軟而瘋狂

直到它擊中頁面。

我曾撫摸過他們的情緒和語調

那些辭世百年的男男女女

艾米麗·迪金森的大狗,康拉德的鬍子

然後,為了我自己

將他們從歷史川流中分離出來。

我已經品嚐過他們的頭腦。聽過

幾聲垂死時發出的濕咳。

他們想象的無暇時刻就是現在。

流言前赴後繼

流言前赴後繼

種進土裏

直至成為脊梁。

(金雯 譯)

像烏鴉一般甜蜜

緻赫蒂.柯利亞, 八歲

“僧伽羅人無疑是世界上最沒有音樂天分的一群人。

幾乎不可能比他們更缺乏音調、節奏和韻律感。”

保羅.波爾斯

你的聲音像一隻蝎子被推着

穿過一根玻璃管子

像一個人踩到孔雀

像椰子裏嚎叫的風

像銹蝕的聖經,像有人拉扯着刺鋼絲

拖過鋪着石塊的院子,像快淹死的豬,

像瓦塔卡菜在煎炸

像晃動着骨頭的手掌

像一隻在卡內基大廳演唱的青蛙。

像一隻奶牛在牛奶中遊泳,

想一隻鼻子讓芒果擊中

像皇-托板球賽時候的人群,

像承載雙胞胎的子宮,像一條流浪狗

嘴裏叼着一隻喜鵲

像來自卡薩布蘭卡的紅眼飛機

像巴基斯坦航班的咖喱,

像着了火的打字機,像一百衹

扁豆脆薄餅被捏碎,像一個人

在黑漆漆的房間裏點火柴,

像把頭伸進海水裏去聽到的礁石噠噠聲

像一隻海豚對着昏睡的聽衆背誦史詩,

像一個人對着電扇扔茄子,

像貝塔集市裏切菠蘿的聲音

像檳榔汁打到半空中的蝴蝶

像一個村子的人在街上躶體奔跑

把布裙撕碎,一個憤怒的傢族

像把吉普車推出泥沼,像針尖上的塵土,

像自行車後座堆着的八條鯊魚

被關在厠所裏的三個老婦人

就像我下午打盹時候聽到的聲音

好似有人戴着腳環穿過我的房間。

(金雯 譯)

懸 崖

他躺在床上,醒着,握着她的左前臂。凌晨四點。他翻了個身,眼睛粗魯地瞪着夜空。透過窗戶他能聽到溪流聲——它沒有名字。昨天正午他沿着清淺的溪水散步,溪流上覆蓋着雪鬆,旁邊是蘆葦、青苔和豆瓣菜。那景象猶如緑灰膚色夾雜的身體,一幅繁復的骨架,他在裏面穿着一雙舊匡威跑步鞋跌跌撞撞地走着。她在上流仔細勘察,而他自顧自探索,時而鑽到連根拔起枝椏顫動的樹下。粗長的樹幹橫亙在溪流上。他用左手抓住巨大幹枯的樹根鑽到底下的白色溪水裏去,感受水流在身上起伏。襯衫浸濕了,他跟隨着水流的肌理迅速滑到樹底下去。他早些時候的夢境一定早就預示了這一切。

他在河裏尋找一座他們前一天走過的木橋。他自信地走着,白色的鞋子不經意地離開樹幹踏入深水,穿過砂礫和豆瓣菜,之後吃一隻夾着豆瓣菜的奶酪三文治。她在走回小木屋的路上已經咀嚼了大半個三文治。他轉過身來,她便僵住了,大笑起來,嘴裏還嚼着豆瓣菜。他除此之外沒有更多可以說愛她的辦法。他假裝生氣,大喊起來,但是奔騰的溪水聲掩蓋了他的聲音

她知道他也同樣喜愛河水的質地。看到一條河流或溪流,他就會走到水邊。會走進齊腰深的水流,聽水流和岩石的聲音將他包裹在孤獨中。如果他們間距超過五英尺,周圍的噪音就會迫使他們停止交談。直到後來,他們坐在水池邊,腿靠着腿,才能開始說話,話題散漫,包括親戚、書籍、最好的朋友,路易斯和剋拉剋的歷史,他們共同拼接起來的過去的碎片。除此之外,水流聲包圍着他們,如今他單獨一人與水中精靈共行,劈啪聲和飛濺聲,嫩枝斷裂聲,假如有什麽事發生在一臂距離之內,他就被那一個聲音占據。現在,他在尋找一個名字。

不是給地圖找名字——他知道有關帝國主義的論爭。是給他們的名字,給他們詞彙的臨時指令。一個暗號。他鑽到倒下的樹下,握着雪鬆的根就好像握着她的前臂。他短暫地懸空,湍急的河水拉扯着他。他緊緊抓住雪鬆,像抓住她的前臂,理由也一樣。心靈河?手臂河?他寫道,在黑暗裏和她喃喃而語。身體從一邊晃到另 一邊,他一隻手挂在樹上,滿是狂喜,無法控製自己,還是牢牢抓着。然後他跳下來,背脊觸碰砂礫和木屑水流蓋過他頭頂,像是戴着手套的手鼓掌。他睜着眼睛,河流推着他站立起來的時候,他已經嚮下遊衝了三英尺,從震動和寒冷中走出來,走到陽光裏。眼光灑下字謎,隨地亂擲,覆蓋整條彎麯的河流,所以他既可以踏入陽光也可以踏入陰影。

他想起了她所在的地方,她的命名。在她附近的草地上,盛開着膀胱草,惡魔畫筆草,還有不知名的藍色小花。他冰冷地站着,在高聳大樹的陰影下一動不動。他為了尋找一座橋已經走得夠遠,還沒找到。繼續嚮上遊走。他抓住了雪鬆的根,就好比抓住她的前臂。

(金雯 譯)

(inner Tube)

On the warm July river

head back

upside down river

for a roof

slowly paddling

towards an estuary between trees

there's a dog

learning to swim near me

friends on shore

my head

dips

back to the eyebrow

I'm the prow

on an ancient vessel,

this afternoon

I'm going down to Peru

soul between my teeth

a blue heron

with its awkward

broken backed flap

upside down

one of us is wrong

he

his blue grey thud

thinking he knows

the blue way

out of here

or me

Kissing the stomach

Kissing the stomach

kissing your scarred

skin boat. History

is what you've travelled on

and take with you

We've each had our stomachs

kissed by strangers

to the other

and as for me

I bless everyone

who kissed you here

What were the names of the towns

What were the names of the towns

we drove into and through

stunned lost

having drunk our way

up vineyards

and then Hot Springs

boiling out the drunkenness

What were the names

I slept through

my head

on your thigh

hundreds of miles

of blackness entering the car

All this

darkness and stars

but now

under the Napa Valley night

a star arch of dashboard

the ripe grape moon

we are together

and I love this muscle

I love this muscle

that tenses

and joins

the accelerator

to my cheek

Michael Ondaatje

Bearhug

Griffin calls to come and kiss him goodnight

I yell ok. Finish something I'm doing,

then something else, walk slowly round

the corner to my son's room.

He is standing arms outstretched

waiting for a bearhug. Grinning.

Why do I give my emotion an animal's name,

give it that dark squeeze of death?

This is the hug which collects

all his small bones and his warm neck against me.

The thin tough body under the pyjamas

locks to me like a magnet of blood.

How long was he standing there

like that, before I came?

Elizabeth

Catch, my Uncle Jack said

and oh I caught this huge apple

red as Mrs Kelly's bum.

It's red as Mrs Kelly's bum, I said

and Daddy roared

and swung me on his stomach with a heave.

Then I hid the apple in my room

till it shrunk like a face

growing eyes and teeth ribs.

Then Daddy took me to the zoo

he knew the man there

they put a snake around my neck

and it crawled down the front of my dress

I felt its flicking tongue

dripping onto me like a shower.

Daddy laughed and said Smart Snake

and Mrs Kelly with us scowled.

In the pond where they kept the goldfish

Philip and I broke the ice with spades

and tried to spear the fishes;

we killed one and Philip ate it,

then he kissed me

with the raw saltless fish in his mouth.

My sister Mary's got bad teeth

and said I was lucky, hen she said

I had big teeth, but Philip said I was pretty.

He had big hands that smelled.

I would speak of Tom', soft laughing,

who danced in the mornings round the sundial

teaching me the steps of France, turning

with the rhythm of the sun on the warped branches,

who'd hold my breast and watch it move like a snail

leaving his quick urgent love in my palm.

And I kept his love in my palm till it blistered.

When they axed his shoulders and neck

the blood moved like a branch into the crowd.

And he staggered with his hanging shoulder

cursing their thrilled cry, wheeling,

waltzing in the French style to his knees

holding his head with the ground,

blood settling on his clothes like a blush;

this way

when they aimed the thud into his back.

And I find cool entertainment now

with white young Essex, and my nimble rhymes.

Last Ink

In certain countries aromas pierce the heart and one dies

half waking in the night as an owl and a murderer's cart go by

the way someone in your life will talk out love and grief

then leave your company laughing.

In certain languages the calligraphy celebrates

where you met the plum blossom and moon by chance

—the dusk light, the cloud pattern,

recorded always in your heart

and the rest of the world—chaos,

circling your winter boat.

Night of the Plum and Moon.

Years later you shared it

on a scroll or nudged

the ink onto stone

to hold the vista of a life.

A condensary of time in the mountains

—your rain-swollen gate, a summer

scarce with human meeting.

Just bells from another village.

The memory of a woman walking down stairs.

Life on an ancient leaf

or a crowded 5th-century seal

this mirror-world of art

—lying on it as if a bed.

When you first saw her,

the night of moon and plum,

you could speak of this to no one.

You cut your desire

against a river stone.

You caught yourself

in a cicada-wing rubbing,

lightly inked.

The indelible darker self.

A seal, the Masters said,

must contain bowing and leaping,

'and that which hides in waters.'

Yellow, drunk with ink,

the scroll unrolls to the west

a river journey, each story

an owl in the dark, its child-howl

unreachable now

—that father and daughter,

that lover walking naked down blue stairs

each step jarring the humming from her mouth.

I want to die on your chest but not yet,

she wrote, sometime in the 13 th century

of our love

before the yellow age of paper

before her story became a song,

lost in imprecise reproductions

until caught in jade,

whose spectrum could hold the black greens

the chalk-blue of her eyes in daylight.

Our altering love, our moonless faith.

Last ink in the pen.

My body on this hard bed.

The moment in the heart

where I roam restless, searching

for the thin border of the fence

to break through or leap.

Leaping and bowing.

Nine Sentiments (IX)

An old book on the poisons

of madness, a map

of forest monasteries,

a chronicle brought across

the sea in Sanskrit slokas.

I hold all these

but you have become

a ghost for me.

I hold only your shadow

since those days I drove

your nature away.

A falcon who became a coward.

I hold you the way astronomers

draw constellations for each other

in the markets of wisdom

placing shells

on a dark blanket

saying 'these

are the heavens'

calculating the movement

of the great stars

Notes For The Legend Of Salad Woman

Since my wife was born

she must have eaten

the equivalent of two-thirds

of the original garden of Eden.

Not the dripping lush fruit

or the meat in the ribs of animals

but the green salad gardens of that place.

The whole arena of green

would have been eradicated

as if the right filter had been removed

leaving only the skeleton of coarse brightness.

All green ends up eventually

churning in her left cheek.

Her mouth is a laundromat of spinning drowning herbs.

She is never in fields

but is sucking the pith out of grass.

I have noticed the very leaves from flower decorations

grow sparse in their week long performance in our house.

The garden is a dust bowl.

On our last day in Eden as we walked out

she nibbled the leaves at her breasts and crotch.

But there's none to touch

none to equal

the Chlorophyll Kiss

Speaking To You

Speaking to you

this hour

these days when

I have lost the feather of poetry

and the rains

of separation

surround us tock

tock like Go tablets

Everyone has learned

to move carefully

'Dancing' 'laughing' 'bad taste'

is a memory

a tableau behind trees of law

In the midst of love for you

my wife's suffering

anger in every direction

and the children wise

as tough shrubs

but they are not tough

--so I fear

how anything can grow from this

all the wise blood

poured from little cuts

down into the sink

this hour it is not

your body I want

but your quiet company

Step

The ceremonial funeral structure for a monk

made up of thambili palms, white cloth

is only a vessel, disintegrates

completely as his life.

The ending disappears,

replacing itself

with something abstract

as air, a view.

All we'll remember in the last hours

is an afternoon—a lazy lunch

then sleeping together.

Then the disarray of grief.

On the morning of a full moon

in a forest monastery

thirty women in white

meditate on the precepts of the day

until darkness.

They walk those abstract paths

their complete heart

their burning thought focused

on this step, then this step.

In the red brick dusk

of the Sacred Quadrangle,

among holy seven-storey ambitions

where the four Buddhas

of Polonnaruwa

face out to each horizon,

is a lotus pavilion.

Taller than a man

nine lotus stalks of stone

stand solitary in the grass,

pillars that once supported

the floor of another level.

(The sensuous stalk

the sacred flower)

How physical yearning

became permanent.

How desire became devotional

so it held up your house,

your lover's house, the house of your god.

And though it is no longer there,

the pillars once let you step

to a higher room

where there was worship, lighter air.

The Cinnamon Peeler

If I were a cinnamon peeler

I would ride your bed

And leave the yellow bark dust

On your pillow.

Your breasts and shoulders would reek

You could never walk through markets

without the profession of my fingers

floating over you. The blind would

stumble certain of whom they approached

though you might bathe

under rain gutters, monsoon.

Here on the upper thigh

at this smooth pasture

neighbour to you hair

or the crease

that cuts your back. This ankle.

You will be known among strangers

as the cinnamon peeler's wife.

I could hardly glance at you

before marriage

never touch you

--your keen nosed mother, your rough brothers.

I buried my hands

in saffron, disguised them

over smoking tar,

helped the honey gatherers...

When we swam once

I touched you in the water

and our bodies remained free,

you could hold me and be blind of smell.

you climbed the bank and said

this is how you touch other women

the grass cutter's wife, the lime burner's daughter.

And you searched your arms

for the missing perfume

and knew

what good is it

to be the lime burner's daughter

left with no trace

as if not spoken to in the act of love

as if wounded without the pleasure of a scar.

You touched

your belly to my hands

in the dry air and said

I am the cinnamon

Peeler's wife. Smell me.

The Great Tree

Zou Fulei died like a dragon breaking down a wall...

this line composed and ribboned

in cursive script

by his friend the poet Yang Weizhen

whose father built a library

surrounded by hundreds of plum trees

It was Zou Fulei, almost unknown,

who made the best plum flower painting

of any period

One branch lifted into the wind

and his friend's vertical line of character

their tones of ink

—wet to opaque

dark to pale

each sweep and gesture

trained and various

echoing the other's art

In the high plum-surrounded library

where Yang Weizhen studied as a boy

a moveable staircase was pulled away

to ensure his solitary concentration

His great work

'untrammelled' 'eccentric''unorthodox'

'no taint of the superficial'

'no flamboyant movement'

using at times the lifted tails

of archaic script,

sharing with Zou Fulei

his leaps and darknesses

'So I have always held you in my heart...

The great 14th-century poet calligrapher

mourns the death of his friend

Language attacks the paper from the air

There is only a path of blossoms

no flamboyant movement

A night of smoky ink in 1361

a night without a staircase

To A Sad Daughter

All night long the hockey pictures

gaze down at you

sleeping in your tracksuit.

Belligerent goalies are your ideal.

Threats of being traded

cuts and wounds

--all this pleases you.

O my god! you say at breakfast

reading the sports page over the Alpen

as another player breaks his ankle

or assaults the coach.

When I thought of daughters

I wasn't expecting this

but I like this more.

I like all your faults

even your purple moods

when you retreat from everyone

to sit in bed under a quilt.

And when I say 'like'

I mean of course 'love'

but that embarrasses you.

You who feel superior to black and white movies

(coaxed for hours to see Casablanca)

though you were moved

by Creature from the Black Lagoon.

One day I'll come swimming

beside your ship or someone will

and if you hear the siren

listen to it. For if you close your ears

only nothing happens. You will never change.

I don't care if you risk

your life to angry goalies

creatures with webbed feet.

You can enter their caves and castles

their glass laboratories. Just

don't be fooled by anyone but yourself.

This is the first lecture I've given you.

You're 'sweet sixteen' you said.

I'd rather be your closest friend

than your father. I'm not good at advice

you know that, but ride

the ceremonies

until they grow dark.

Sometimes you are so busy

discovering your friends

I ache with loss

--but that is greed.

And sometimes I've gone

into my purple world

and lost you.

One afternoon I stepped

into your room. You were sitting

at the desk where I now write this.

Forsythia outside the window

and sun spilled over you

like a thick yellow miracle

as if another planet

was coaxing you out of the house

--all those possible worlds!--

and you, meanwhile, busy with mathematics.

I cannot look at forsythia now

without loss, or joy for you.

You step delicately

into the wild world

and your real prize will be

the frantic search.

Want everything. If you break

break going out not in.

How you live your life I don't care

but I'll sell my arms for you,

hold your secrets forever.

If I speak of death

which you fear now, greatly,

it is without answers.

except that each

one we know is

in our blood.

Don't recall graves.

Memory is permanent.

Remember the afternoon's

yellow suburban annunciation.

Your goalie

in his frightening mask

dreams perhaps

of gentleness.

Wells II

The last Sinhala word I lost

was vatura.

The word for water.

Forest water. The water in a kiss. The tears

I gave to my ayah Rosalin on leaving

the first home of my life.

More water for her than any other

that fled my eyes again

this year, remembering her,

a lost almost-mother in those years

of thirsty love.

No photograph of her, no meeting

since the age of eleven,

not even knowledge of her grave.

Who abandoned who, I wonder now.