此开卷第一回也。作者自云:因曾历过一番梦幻之后,故将真事隐去,而借"通灵"之说,撰此《石头记》一书也。故曰"甄士隐"云云。但书中所记何事何人?自又云:“今风尘碌碌,一事无成,忽念及当日所有之女子,一一细考较去,觉其行止见识,皆出于我之上。何我堂堂须眉,诚不若彼裙钗哉?实愧则有余,悔又无益之大无可如何之日也!当此,则自欲将已往所赖天恩祖德,锦衣纨绔之时,饫甘餍肥之日,背父兄教育之恩,负师友规谈之德,以至今日一技无成,半生潦倒之罪,编述一集,以告天下人:我之罪固不免,然闺阁中本自历历有人,万不可因我之不肖,自护己短,一并使其泯灭也。虽今日之茅椽蓬牖,瓦灶绳床,其晨夕风露,阶柳庭花,亦未有妨我之襟怀笔墨者。虽我未学,下笔无文,又何妨用假语村言,敷演出一段故事来,亦可使闺阁昭传,复可悦世之目,破人愁闷,不亦宜乎?"故曰"贾雨村"云云。

此回中凡用“梦”用“幻”等字,是提醒阅者眼目,亦是此书立意本旨。

列位看官:你道此书从何而来?说起根由虽近荒唐,细按则深有趣味。待在下将此来历注明,方使阅者了然不惑。

原来女娲氏炼石补天之时,于大荒山无稽崖练成高经十二丈,方经二十四丈顽石三万六千五百零一块。娲皇氏只用了三万六千五百块,只单单剩了一块未用,便弃在此山青埂峰下。谁知此石自经煅炼之后,灵性已通,因见众石俱得补天,独自己无材不堪入选,遂自怨自叹,日夜悲号惭愧。

一日,正当嗟悼之际,俄见一僧一道远远而来,生得骨骼不凡,丰神迥异,说说笑笑来至峰下,坐于石边高谈快论。先是说些云山雾海神仙玄幻之事,后便说到红尘中荣华富贵。此石听了,不觉打动凡心,也想要到人间去享一享这荣华富贵,但自恨粗蠢,不得已,便口吐人言,向那僧道说道:“大师,弟子蠢物,不能见礼了。适闻二位谈那人世间荣耀繁华,心切慕之。弟子质虽粗蠢,性却稍通,况见二师仙形道体,定非凡品,必有补天济世之材,利物济人之德。如蒙发一点慈心,携带弟子得入红尘,在那富贵场中,温柔乡里受享几年,自当永佩洪恩,万劫不忘也。”二仙师听毕,齐憨笑道:“善哉,善哉!那红尘中有却有些乐事,但不能永远依恃,况又有‘美中不足,好事多魔’八个字紧相连属,瞬息间则又乐极悲生,人非物换,究竟是到头一梦,万境归空,倒不如不去的好。”这石凡心已炽,那里听得进这话去,乃复苦求再四。二仙知不可强制,乃叹道:“此亦静极怂级*,无中生有之数也。既如此,我们便携你去受享受享,只是到不得意时,切莫后悔。”石道:“自然,自然。”那僧又道:“若说你性灵,却又如此质蠢,并更无奇贵之处。如此也只好踮脚而已。也罢,我如今大施佛法助你助,待劫终之日,复还本质,以了此案。你道好否?"石头听了,感谢不尽。那僧便念咒书符,大展幻术,将一块大石登时变成一块鲜明莹洁的美玉,且又缩成扇坠大小的可佩可拿。那僧托于掌上,笑道:“形体倒也是个宝物了!还只没有,实在的好处,须得再镌上数字,使人一见便知是奇物方妙。然后携你到那昌明隆盛之邦,诗礼簪缨之族,花柳繁华地,温柔富贵乡去安身乐业。”石头听了,喜不能禁,乃问:“不知赐了弟子那几件奇处,又不知携了弟子到何地方?望乞明示,使弟子不惑。”那僧笑道:“你且莫问,日后自然明白的。”说着,便袖了这石,同那道人飘然而去,竟不知投奔何方何舍。

后来,又不知过了几世几劫,因有个空空道人访道求仙,忽从这大荒山无稽崖青埂峰下经过,忽见一大块石上字迹分明,编述历历。空空道人乃从头一看,原来就是无材补天,幻形入世,蒙茫茫大士,渺渺真人携入红尘,历尽离合悲欢炎凉世态的一段故事。后面又有一首偈云:

无材可去补苍天,枉入红尘若许年。

此系身前身后事,倩谁记去作奇传?诗后便是此石坠落之乡,投胎之处,亲自经历的一段陈迹故事。其中家庭闺阁琐事,以及闲情诗词倒还全备,或可适趣解闷,然朝代年纪,地舆邦国,却反失落无考。

空空道人遂向石头说道:“石兄,你这一段故事,据你自己说有些趣味,故编写在此,意欲问世传奇。据我看来,第一件,无朝代年纪可考,第二件,并无大贤大忠理朝廷治风俗的善政,其中只不过几个异样女子,或情或痴,或小才微善,亦无班姑,蔡女之德能。我纵抄去,恐世人不爱看呢。”石头笑答道:“我师何太痴耶!若云无朝代可考,今我师竟假借汉唐等年纪添缀,又有何难?但我想,历来野史,皆蹈一辙,莫如我这不借此套者,反倒新奇别致,不过只取其事体情理罢了,又何必拘拘于朝代年纪哉!再者,市井俗人喜看理治之书者甚少,爱适趣闲文者特多。历来野史,或讪谤君相,或贬人妻女,奸淫凶恶,不可胜数。更有一种风月笔墨,其淫秽污臭,屠毒笔墨,坏人子弟,又不可胜数。至若佳人才子等书,则又千部共出一套,且其中终不能不涉于淫滥,以致满纸潘安,子建,西子,文君,不过作者要写出自己的那两首情诗艳赋来,故假拟出男女二人名姓,又必旁出一小人其间拨乱,亦如剧中之小丑然。且鬟婢开口即者也之乎,非文即理。故逐一看去,悉皆自相矛盾,大不近情理之话,竟不如我半世亲睹亲闻的这几个女子,虽不敢说强似前代书中所有之人,但事迹原委,亦可以消愁破闷,也有几首歪诗熟话,可以喷饭供酒。至若离合悲欢,兴衰际遇,则又追踪蹑迹,不敢稍加穿凿,徒为供人之目而反失其真传者。今之人,贫者日为衣食所累,富者又怀不足之心,纵然一时稍闲,又有贪淫恋色,好货寻愁之事,那里去有工夫看那理治之书?所以我这一段故事,也不愿世人称奇道妙,也不定要世人喜悦检读,只愿他们当那醉淫饱卧之时,或避世去愁之际,把此一玩,岂不省了些寿命筋力?就比那谋虚逐妄,却也省了口舌是非之害,腿脚奔忙之苦。再者,亦令世人换新眼目,不比那些胡牵乱扯,忽离忽遇,满纸才人淑女,子建文君红娘小玉等通共熟套之旧稿。我师意为何如?”

空空道人听如此说,思忖半晌,将《石头记》再检阅一遍,因见上面虽有些指奸责佞贬恶诛邪之语,亦非伤时骂世之旨,及至君仁臣良父慈子孝,凡伦常所关之处,皆是称功颂德,眷眷无穷,实非别书之可比。虽其中大旨谈情,亦不过实录其事,又非假拟妄称,一味淫邀艳约,私订偷盟之可比。因毫不干涉时世,方从头至尾抄录回来,问世传奇。从此空空道人因空见色,由色生情,传情入色,自色悟空,遂易名为情僧,改《石头记》为《情僧录》。东鲁孔梅溪则题曰《风月宝鉴》。后因曹雪芹于悼红轩中披阅十载,增删五次,纂成目录,分出章回,则题曰《金陵十二钗》。并题一绝云:

满纸荒唐言,一把辛酸泪!

都云作者痴,谁解其中味?

出则既明,且看石上是何故事。按那石上书云:

当日地陷东南,这东南一隅有处曰姑苏,有城曰阊门者,最是红尘中一二等富贵风流之地。这阊门外有个十里街,街内有个仁清巷,巷内有个古庙,因地方窄狭,人皆呼作葫芦庙。庙旁住着一家乡宦,姓甄,名费,字士隐。嫡妻封氏,情性贤淑,深明礼义。家中虽不甚富贵,然本地便也推他为望族了。因这甄士隐禀性恬淡,不以功名为念,每日只以观花修竹,酌酒吟诗为乐,倒是神仙一流人品。只是一件不足:如今年已半百,膝下无儿,只有一女,乳名唤作英莲,年方三岁。

一日,炎夏永昼,士隐于书房闲坐,至手倦抛书,伏几少憩,不觉朦胧睡去。梦至一处,不辨是何地方。忽见那厢来了一僧一道,且行且谈。只听道人问道:“你携了这蠢物,意欲何往?"那僧笑道:“你放心,如今现有一段风流公案正该了结,这一干风流冤家,尚未投胎入世。趁此机会,就将此蠢物夹带于中,使他去经历经历。”那道人道:“原来近日风流冤孽又将造劫历世去不成?但不知落于何方何处?"那僧笑道:“此事说来好笑,竟是千古未闻的罕事。只因西方灵河岸上三生石畔,有绛珠草一株,时有赤瑕宫神瑛侍者,日以甘露灌溉,这绛珠草始得久延岁月。后来既受天地精华,复得雨露滋养,遂得脱却草胎木质,得换人形,仅修成个女体,终日游于离恨天外,饥则食蜜青果为膳,渴则饮灌愁海水为汤。只因尚未酬报灌溉之德,故其五内便郁结着一段缠绵不尽之意。恰近日这神瑛侍者凡心偶炽,乘此昌明太平朝世,意欲下凡造历幻缘,已在警幻仙子案前挂了号。警幻亦曾问及,灌溉之情未偿,趁此倒可了结的。那绛珠仙子道:‘他是甘露之惠,我并无此水可还。他既下世为人,我也去下世为人,但把我一生所有的眼泪还他,也偿还得过他了。’因此一事,就勾出多少风流冤家来,陪他们去了结此案。”那道人道:“果是罕闻。实未闻有还泪之说。想来这一段故事,比历来风月事故更加琐碎细腻了。”那僧道:“历来几个风流人物,不过传其大概以及诗词篇章而已,至家庭闺阁中一饮一食,总未述记。再者,大半风月故事,不过偷香窃玉,暗约私奔而已,并不曾将儿女之真情发泄一二。想这一干人入世,其情痴色鬼,贤愚不肖者,悉与前人传述不同矣。”那道人道:“趁此何不你我也去下世度脱几个,岂不是一场功德?"那僧道:“正合吾意,你且同我到警幻仙子宫中,将蠢物交割清楚,待这一干风流孽鬼下世已完,你我再去。如今虽已有一半落尘,然犹未全集。”道人道:“既如此,便随你去来。”

却说甄士隐俱听得明白,但不知所云"蠢物"系何东西。遂不禁上前施礼,笑问道:“二仙师请了。”那僧道也忙答礼相问。士隐因说道:“适闻仙师所谈因果,实人世罕闻者。但弟子愚浊,不能洞悉明白,若蒙大开痴顽,备细一闻,弟子则洗耳谛听,稍能警省,亦可免沉伦之苦。”二仙笑道:“此乃玄机不可预泄者。到那时不要忘我二人,便可跳出火坑矣。”士隐听了,不便再问。因笑道:“玄机不可预泄,但适云‘蠢物’,不知为何,或可一见否?"那僧道:“若问此物,倒有一面之缘。”说着,取出递与士隐。士隐接了看时,原来是块鲜明美玉,上面字迹分明,镌着"通灵宝玉"四字,后面还有几行小字。正欲细看时,那僧便说已到幻境,便强从手中夺了去,与道人竟过一大石牌坊,上书四个大字,乃是"太虚幻境"。两边又有一幅对联,道是:

假作真时真亦假,无为有处有还无。士隐意欲也跟了过去,方举步时,忽听一声霹雳,有若山崩地陷。士隐大叫一声,定睛一看,只见烈日炎炎,芭蕉冉冉,所梦之事便忘了大半。又见奶母正抱了英莲走来。士隐见女儿越发生得粉妆玉琢,乖觉可喜,便伸手接来,抱在怀内,斗他顽耍一回,又带至街前,看那过会的热闹。方欲进来时,只见从那边来了一僧一道:那僧则癞头跣脚,那道则跛足蓬头,疯疯癫癫,挥霍谈笑而至。及至到了他门前,看见士隐抱着英莲,那僧便大哭起来,又向士隐道:“施主,你把这有命无运,累及爹娘之物,抱在怀内作甚?"士隐听了,知是疯话,也不去睬他。那僧还说:“舍我罢,舍我罢!"士隐不耐烦,便抱女儿撤身要进去,那僧乃指着他大笑,口内念了四句言词道:

惯养娇生笑你痴,菱花空对雪澌澌。

好防佳节元宵后,便是烟消火灭时。士隐听得明白,心下犹豫,意欲问他们来历。只听道人说道:“你我不必同行,就此分手,各干营生去罢。三劫后,我在北邙山等你,会齐了同往太虚幻境销号。”那僧道:“最妙,最妙!"说毕,二人一去,再不见个踪影了。士隐心中此时自忖:这两个人必有来历,该试一问,如今悔却晚也。

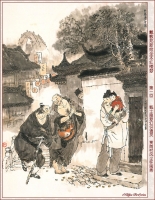

这士隐正痴想,忽见隔壁葫芦庙内寄居的一个穷儒-姓贾名化,表字时飞,别号雨村者走了出来。这贾雨村原系胡州人氏,也是诗书仕宦之族,因他生于末世,父母祖宗根基已尽,人口衰丧,只剩得他一身一口,在家乡无益,因进京求取功名,再整基业。自前岁来此,又淹蹇住了,暂寄庙中安身,每日卖字作文为生,故士隐常与他交接。当下雨村见了士隐,忙施礼陪笑道:“老先生倚门伫望,敢是街市上有甚新闻否?"士隐笑道:“非也。适因小女啼哭,引他出来作耍,正是无聊之甚,兄来得正妙,请入小斋一谈,彼此皆可消此永昼。”说着,便令人送女儿进去,自与雨村携手来至书房中。小童献茶。方谈得三五句话,忽家人飞报:“严老爷来拜。”士隐慌的忙起身谢罪道:“恕诳驾之罪,略坐,弟即来陪。”雨村忙起身亦让道:“老先生请便。晚生乃常造之客,稍候何妨。”说着,士隐已出前厅去了。

这里雨村且翻弄书籍解闷。忽听得窗外有女子嗽声,雨村遂起身往窗外一看,原来是一个丫鬟,在那里撷花,生得仪容不俗,眉目清明,虽无十分姿色,却亦有动人之处。雨村不觉看的呆了。那甄家丫鬟撷了花,方欲走时,猛抬头见窗内有人,敝巾旧服,虽是贫窘,然生得腰圆背厚,面阔口方,更兼剑眉星眼,直鼻权腮。这丫鬟忙转身回避,心下乃想:“这人生的这样雄壮,却又这样褴褛,想他定是我家主人常说的什么贾雨村了,每有意帮助周济,只是没甚机会。我家并无这样贫窘亲友,想定是此人无疑了。怪道又说他必非久困之人。”如此想来,不免又回头两次。雨村见他回了头,便自为这女子心中有意于他,便狂喜不尽,自为此女子必是个巨眼英雄,风尘中之知己也。一时小童进来,雨村打听得前面留饭,不可久待,遂从夹道中自便出门去了。士隐待客既散,知雨村自便,也不去再邀。

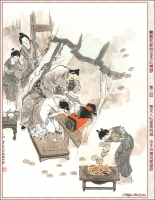

一日,早又中秋佳节。士隐家宴已毕,乃又另具一席于书房,却自己步月至庙中来邀雨村。原来雨村自那日见了甄家之婢曾回顾他两次,自为是个知己,便时刻放在心上。今又正值中秋,不免对月有怀,因而口占五言一律云:

未卜三生愿,频添一段愁。

闷来时敛额,行去几回头。

自顾风前影,谁堪月下俦?

蟾光如有意,先上玉人楼。

雨村吟罢,因又思及平生抱负,苦未逢时,乃又搔首对天长叹,复高吟一联曰:

玉在匣中求善价,钗于奁内待时飞。

恰值士隐走来听见,笑道:“雨村兄真抱负不浅也!"雨村忙笑道:“不过偶吟前人之句,何敢狂诞至此。”因问:“老先生何兴至此?"士隐笑道:“今夜中秋,俗谓‘团圆之节’,想尊兄旅寄僧房,不无寂寥之感,故特具小酌,邀兄到敝斋一饮,不知可纳芹意否?"雨村听了,并不推辞,便笑道:“既蒙厚爱,何敢拂此盛情。”说着,便同士隐复过这边书院中来。须臾茶毕,早已设下杯盘,那美酒佳肴自不必说。二人归坐,先是款斟漫饮,次渐谈至兴浓,不觉飞觥限起来。当时街坊上家家箫管,户户弦歌,当头一轮明月,飞彩凝辉,二人愈添豪兴,酒到杯干。雨村此时已有七八分酒意,狂兴不禁,乃对月寓怀,口号一绝云:

时逢三五便团圆,满把晴光护玉栏。

天上一轮才捧出,人间万姓仰头看。士隐听了,大叫:“妙哉!吾每谓兄必非久居人下者,今所吟之句,飞腾之兆已见,不日可接履于云霓之上矣。可贺,可贺!"乃亲斟一斗为贺。雨村因干过,叹道:“非晚生酒后狂言,若论时尚之学,晚生也或可去充数沽名,只是目今行囊路费一概无措,神京路远,非赖卖字撰文即能到者。”士隐不待说完,便道:“兄何不早言。愚每有此心,但每遇兄时,兄并未谈及,愚故未敢唐突。今既及此,愚虽不才,‘义利’二字却还识得。且喜明岁正当大比,兄宜作速入都,春闱一战,方不负兄之所学也。其盘费余事,弟自代为处置,亦不枉兄之谬识矣!"当下即命小童进去,速封五十两白银,并两套冬衣。又云:“十九日乃黄道之期,兄可即买舟西上,待雄飞高举,明冬再晤,岂非大快之事耶!"雨村收了银衣,不过略谢一语,并不介意,仍是吃酒谈笑。那天已交了三更,二人方散。士隐送雨村去后,回房一觉,直至红日三竿方醒。因思昨夜之事,意欲再写两封荐书与雨村带至神都,使雨村投谒个仕宦之家为寄足之地。因使人过去请时,那家人去了回来说:“和尚说,贾爷今日五鼓已进京去了,也曾留下话与和尚转达老爷,说‘读书人不在黄道黑道,总以事理为要,不及面辞了。’"士隐听了,也只得罢了。真是闲处光阴易过,倏忽又是元霄佳节矣。士隐命家人霍启抱了英莲去看社火花灯,半夜中,霍启因要小解,便将英莲放在一家门槛上坐着。待他小解完了来抱时,那有英莲的踪影?急得霍启直寻了半夜,至天明不见,那霍启也就不敢回来见主人,便逃往他乡去了。那士隐夫妇,见女儿一夜不归,便知有些不妥,再使几人去寻找,回来皆云连音响皆无。夫妻二人,半世只生此女,一旦失落,岂不思想,因此昼夜啼哭,几乎不曾寻死。看看的一月,士隐先就得了一病,当时封氏孺人也因思女构疾,日日请医疗治。

不想这日三月十五,葫芦庙中炸供,那些和尚不加小心,致使油锅火逸,便烧着窗纸。此方人家多用竹篱木壁者,大抵也因劫数,于是接二连三,牵五挂四,将一条街烧得如火焰山一般。彼时虽有军民来救,那火已成了势,如何救得下?直烧了一夜,方渐渐的熄去,也不知烧了几家。只可怜甄家在隔壁,早已烧成一片瓦砾场了。只有他夫妇并几个家人的性命不曾伤了。急得士隐惟跌足长叹而已。只得与妻子商议,且到田庄上去安身。偏值近年水旱不收,鼠盗蜂起,无非抢田夺地,鼠窃狗偷,民不安生,因此官兵剿捕,难以安身。士隐只得将田庄都折变了,便携了妻子与两个丫鬟投他岳丈家去。

他岳丈名唤封肃,本贯大如州人氏,虽是务农,家中都还殷实。今见女婿这等狼狈而来,心中便有些不乐。幸而士隐还有折变田地的银子未曾用完,拿出来托他随分就价薄置些须房地,为后日衣食之计。那封肃便半哄半赚,些须与他些薄田朽屋。士隐乃读书之人,不惯生理稼穑等事,勉强支持了一二年,越觉穷了下去。封肃每见面时,便说些现成话,且人前人后又怨他们不善过活,只一味好吃懒作等语。士隐知投人不着,心中未免悔恨,再兼上年惊唬,急忿怨痛,已有积伤,暮年之人,贫病交攻,竟渐渐的露出那下世的光景来。

可巧这日拄了拐杖挣挫到街前散散心时,忽见那边来了一个跛足道人,疯癫落脱,麻屣鹑衣,口内念着几句言词,道是:

世人都晓神仙好,惟有功名忘不了!

古今将相在何方?荒冢一堆草没了。

世人都晓神仙好,只有金银忘不了!

终朝只恨聚无多,及到多时眼闭了。

世人都晓神仙好,只有姣妻忘不了!

君生日日说恩情,君死又随人去了。

世人都晓神仙好,只有儿孙忘不了!

痴心父母古来多,孝顺儿孙谁见了?

士隐听了,便迎上来道:“你满口说些什么?只听见些‘好’‘了’‘好’‘了’。那道人笑道:“你若果听见‘好’‘了’二字,还算你明白。可知世上万般,好便是了,了便是好。若不了,便不好,若要好,须是了。我这歌儿,便名《好了歌》"士隐本是有宿慧的,一闻此言,心中早已彻悟。因笑道:“且住!待我将你这《好了歌》解注出来何如?"道人笑道:“你解,你解。”士隐乃说道:

陋室空堂,当年笏满床,衰草枯杨,曾为歌舞场。蛛丝儿结满雕梁,绿纱今又糊在蓬窗上。说什么脂正浓、粉正香,如何两鬓又成霜?昨日黄土陇头送白骨,今宵红灯帐底卧鸳鸯。金满箱,银满箱,展眼乞丐人皆谤。正叹他人命不长,那知自己归来丧!训有方,保不定日后作强梁。择膏粱,谁承望流落在烟花巷!因嫌纱帽小,致使锁枷杠,昨怜破袄寒,今嫌紫蟒长:乱烘烘你方唱罢我登场,反认他乡是故乡。甚荒唐,到头来都是为他人作嫁衣裳!

那疯跛道人听了,拍掌笑道:“解得切,解得切!"士隐便说一声"走罢!"将道人肩上褡裢抢了过来背着,竟不回家,同了疯道人飘飘而去。当下烘动街坊,众人当作一件新闻传说。封氏闻得此信,哭个死去活来,只得与父亲商议,遣人各处访寻,那讨音信?无奈何,少不得依靠着他父母度日。幸而身边还有两个旧日的丫鬟伏侍,主仆三人,日夜作些针线发卖,帮着父亲用度。那封肃虽然日日抱怨,也无可奈何了。

这日,那甄家大丫鬟在门前买线,忽听街上喝道之声,众人都说新太爷到任。丫鬟于是隐在门内看时,只见军牢快手,一对一对的过去,俄而大轿抬着一个乌帽猩袍的官府过去。丫鬟倒发了个怔,自思这官好面善,倒象在那里见过的。于是进入房中,也就丢过不在心上。至晚间,正待歇息之时,忽听一片声打的门响,许多人乱嚷,说:“本府太爷差人来传人问话。”封肃听了,唬得目瞪口呆,不知有何祸事。

This is the opening section; this the first chapter. Subsequent to the visions of a dream which he had, on some previous occasion, experienced, the writer personally relates, he designedly concealed the true circumstances, and borrowed the attributes of perception and spirituality to relate this story of the Record of the Stone. With this purpose, he made use of such designations as Chen Shih-yin (truth under the garb of fiction) and the like. What are, however, the events recorded in this work? Who are the dramatis personae?

Wearied with the drudgery experienced of late in the world, the author speaking for himself, goes on to explain, with the lack of success which attended every single concern, I suddenly bethought myself of the womankind of past ages. Passing one by one under a minute scrutiny, I felt that in action and in lore, one and all were far above me; that in spite of the majesty of my manliness, I could not, in point of fact, compare with these characters of the gentle sex. And my shame forsooth then knew no bounds; while regret, on the other hand, was of no avail, as there was not even a remote possibility of a day of remedy.

On this very day it was that I became desirous to compile, in a connected form, for publication throughout the world, with a view to (universal) information, how that I bear inexorable and manifold retribution; inasmuch as what time, by the sustenance of the benevolence of Heaven, and the virtue of my ancestors, my apparel was rich and fine, and as what days my fare was savory and sumptuous, I disregarded the bounty of education and nurture of father and mother, and paid no heed to the virtue of precept and injunction of teachers and friends, with the result that I incurred the punishment, of failure recently in the least trifle, and the reckless waste of half my lifetime. There have been meanwhile, generation after generation, those in the inner chambers, the whole mass of whom could not, on any account, be, through my influence, allowed to fall into extinction, in order that I, unfilial as I have been, may have the means to screen my own shortcomings.

Hence it is that the thatched shed, with bamboo mat windows, the bed of tow and the stove of brick, which are at present my share, are not sufficient to deter me from carrying out the fixed purpose of my mind. And could I, furthermore, confront the morning breeze, the evening moon, the willows by the steps and the flowers in the courtyard, methinks these would moisten to a greater degree my mortal pen with ink; but though I lack culture and erudition, what harm is there, however, in employing fiction and unrecondite language to give utterance to the merits of these characters? And were I also able to induce the inmates of the inner chamber to understand and diffuse them, could I besides break the weariness of even so much as a single moment, or could I open the eyes of my contemporaries, will it not forsooth prove a boon?

This consideration has led to the usage of such names as Chia Yue-ts'un and other similar appellations.

More than any in these pages have been employed such words as dreams and visions; but these dreams constitute the main argument of this work, and combine, furthermore, the design of giving a word of warning to my readers.

Reader, can you suggest whence the story begins?

The narration may border on the limits of incoherency and triviality, but it possesses considerable zest. But to begin.

The Empress Nue Wo, (the goddess of works,) in fashioning blocks of stones, for the repair of the heavens, prepared, at the Ta Huang Hills and Wu Ch'i cave, 36,501 blocks of rough stone, each twelve chang in height, and twenty-four chang square. Of these stones, the Empress Wo only used 36,500; so that one single block remained over and above, without being turned to any account. This was cast down the Ch'ing Keng peak. This stone, strange to say, after having undergone a process of refinement, attained a nature of efficiency, and could, by its innate powers, set itself into motion and was able to expand and to contract.

When it became aware that the whole number of blocks had been made use of to repair the heavens, that it alone had been destitute of the necessary properties and had been unfit to attain selection, it forthwith felt within itself vexation and shame, and day and night, it gave way to anguish and sorrow.

One day, while it lamented its lot, it suddenly caught sight, at a great distance, of a Buddhist bonze and of a Taoist priest coming towards that direction. Their appearance was uncommon, their easy manner remarkable. When they drew near this Ch'ing Keng peak, they sat on the ground to rest, and began to converse. But on noticing the block newly-polished and brilliantly clear, which had moreover contracted in dimensions, and become no larger than the pendant of a fan, they were greatly filled with admiration. The Buddhist priest picked it up, and laid it in the palm of his hand.

"Your appearance," he said laughingly, "may well declare you to be a supernatural object, but as you lack any inherent quality it is necessary to inscribe a few characters on you, so that every one who shall see you may at once recognise you to be a remarkable thing. And subsequently, when you will be taken into a country where honour and affluence will reign, into a family cultured in mind and of official status, in a land where flowers and trees shall flourish with luxuriance, in a town of refinement, renown and glory; when you once will have been there..."

The stone listened with intense delight.

"What characters may I ask," it consequently inquired, "will you inscribe? and what place will I be taken to? pray, pray explain to me in lucid terms." "You mustn't be inquisitive," the bonze replied, with a smile, "in days to come you'll certainly understand everything." Having concluded these words, he forthwith put the stone in his sleeve, and proceeded leisurely on his journey, in company with the Taoist priest. Whither, however, he took the stone, is not divulged. Nor can it be known how many centuries and ages elapsed, before a Taoist priest, K'ung K'ung by name, passed, during his researches after the eternal reason and his quest after immortality, by these Ta Huang Hills, Wu Ch'i cave and Ch'ing Keng Peak. Suddenly perceiving a large block of stone, on the surface of which the traces of characters giving, in a connected form, the various incidents of its fate, could be clearly deciphered, K'ung K'ung examined them from first to last. They, in fact, explained how that this block of worthless stone had originally been devoid of the properties essential for the repairs to the heavens, how it would be transmuted into human form and introduced by Mang Mang the High Lord, and Miao Miao, the Divine, into the world of mortals, and how it would be led over the other bank (across the San Sara). On the surface, the record of the spot where it would fall, the place of its birth, as well as various family trifles and trivial love affairs of young ladies, verses, odes, speeches and enigmas was still complete; but the name of the dynasty and the year of the reign were obliterated, and could not be ascertained.

On the obverse, were also the following enigmatical verses:

Lacking in virtues meet the azure skies to mend, In vain the mortal world full many a year I wend, Of a former and after life these facts that be, Who will for a tradition strange record for me?

K'ung K'ung, the Taoist, having pondered over these lines for a while, became aware that this stone had a history of some kind.

"Brother stone," he forthwith said, addressing the stone, "the concerns of past days recorded on you possess, according to your own account, a considerable amount of interest, and have been for this reason inscribed, with the intent of soliciting generations to hand them down as remarkable occurrences. But in my own opinion, they lack, in the first place, any data by means of which to establish the name of the Emperor and the year of his reign; and, in the second place, these constitute no record of any excellent policy, adopted by any high worthies or high loyal statesmen, in the government of the state, or in the rule of public morals. The contents simply treat of a certain number of maidens, of exceptional character; either of their love affairs or infatuations, or of their small deserts or insignificant talents; and were I to transcribe the whole collection of them, they would, nevertheless, not be estimated as a book of any exceptional worth."

"Sir Priest," the stone replied with assurance, "why are you so excessively dull? The dynasties recorded in the rustic histories, which have been written from age to age, have, I am fain to think, invariably assumed, under false pretences, the mere nomenclature of the Han and T'ang dynasties. They differ from the events inscribed on my block, which do not borrow this customary practice, but, being based on my own experiences and natural feelings, present, on the contrary, a novel and unique character. Besides, in the pages of these rustic histories, either the aspersions upon sovereigns and statesmen, or the strictures upon individuals, their wives, and their daughters, or the deeds of licentiousness and violence are too numerous to be computed. Indeed, there is one more kind of loose literature, the wantonness and pollution in which work most easy havoc upon youth.

"As regards the works, in which the characters of scholars and beauties is delineated their allusions are again repeatedly of Wen Chuen, their theme in every page of Tzu Chien; a thousand volumes present no diversity; and a thousand characters are but a counterpart of each other. What is more, these works, throughout all their pages, cannot help bordering on extreme licence. The authors, however, had no other object in view than to give utterance to a few sentimental odes and elegant ballads of their own, and for this reason they have fictitiously invented the names and surnames of both men and women, and necessarily introduced, in addition, some low characters, who should, like a buffoon in a play, create some excitement in the plot.

"Still more loathsome is a kind of pedantic and profligate literature, perfectly devoid of all natural sentiment, full of self-contradictions; and, in fact, the contrast to those maidens in my work, whom I have, during half my lifetime, seen with my own eyes and heard with my own ears. And though I will not presume to estimate them as superior to the heroes and heroines in the works of former ages, yet the perusal of the motives and issues of their experiences, may likewise afford matter sufficient to banish dulness, and to break the spell of melancholy.

"As regards the several stanzas of doggerel verse, they may too evoke such laughter as to compel the reader to blurt out the rice, and to spurt out the wine.

"In these pages, the scenes depicting the anguish of separation, the bliss of reunion, and the fortunes of prosperity and of adversity are all, in every detail, true to human nature, and I have not taken upon myself to make the slightest addition, or alteration, which might lead to the perversion of the truth.

"My only object has been that men may, after a drinking bout, or after they wake from sleep or when in need of relaxation from the pressure of business, take up this light literature, and not only expunge the traces of antiquated books, and obtain a new kind of distraction, but that they may also lay by a long life as well as energy and strength; for it bears no point of similarity to those works, whose designs are false, whose course is immoral. Now, Sir Priest, what are your views on the subject?"

K'ung K'ung having pondered for a while over the words, to which he had listened intently, re-perused, throughout, this record of the stone; and finding that the general purport consisted of nought else than a treatise on love, and likewise of an accurate transcription of facts, without the least taint of profligacy injurious to the times, he thereupon copied the contents, from beginning to end, to the intent of charging the world to hand them down as a strange story.

Hence it was that K'ung K'ung, the Taoist, in consequence of his perception, (in his state of) abstraction, of passion, the generation, from this passion, of voluptuousness, the transmission of this voluptuousness into passion, and the apprehension, by means of passion, of its unreality, forthwith altered his name for that of "Ch'ing Tseng" (the Voluptuous Bonze), and changed the title of "the Memoir of a Stone" (Shih-t'ou-chi,) for that of "Ch'ing Tseng Lu," The Record of the Voluptuous Bonze; while K'ung Mei-chi of Tung Lu gave it the name of "Feng Yueeh Pao Chien," "The Precious Mirror of Voluptuousness." In later years, owing to the devotion by Tsao Hsueeh-ch'in in the Tao Hung study, of ten years to the perusal and revision of the work, the additions and modifications effected by him five times, the affix of an index and the division into periods and chapters, the book was again entitled "Chin Ling Shih Erh Ch'ai," "The Twelve Maidens of Chin Ling." A stanza was furthermore composed for the purpose. This then, and no other, is the origin of the Record of the Stone. The poet says appositely:--

Pages full of silly litter, Tears a handful sour and bitter; All a fool the author hold, But their zest who can unfold?

You have now understood the causes which brought about the Record of the Stone, but as you are not, as yet, aware what characters are depicted, and what circumstances are related on the surface of the block, reader, please lend an ear to the narrative on the stone, which runs as follows:--

In old days, the land in the South East lay low. In this South-East part of the world, was situated a walled town, Ku Su by name. Within the walls a locality, called the Ch'ang Men, was more than all others throughout the mortal world, the centre, which held the second, if not the first place for fashion and life. Beyond this Ch'ang Men was a street called Shih-li-chieh (Ten _Li_ street); in this street a lane, the Jen Ch'ing lane (Humanity and Purity); and in this lane stood an old temple, which on account of its diminutive dimensions, was called, by general consent, the Gourd temple. Next door to this temple lived the family of a district official, Chen by surname, Fei by name, and Shih-yin by style. His wife, nee Feng, possessed a worthy and virtuous disposition, and had a clear perception of moral propriety and good conduct. This family, though not in actual possession of excessive affluence and honours, was, nevertheless, in their district, conceded to be a clan of well-to-do standing. As this Chen Shih-yin was of a contented and unambitious frame of mind, and entertained no hankering after any official distinction, but day after day of his life took delight in gazing at flowers, planting bamboos, sipping his wine and conning poetical works, he was in fact, in the indulgence of these pursuits, as happy as a supernatural being.

One thing alone marred his happiness. He had lived over half a century and had, as yet, no male offspring around his knees. He had one only child, a daughter, whose infant name was Ying Lien. She was just three years of age. On a long summer day, on which the heat had been intense, Shih-yin sat leisurely in his library. Feeling his hand tired, he dropped the book he held, leant his head on a teapoy, and fell asleep.

Of a sudden, while in this state of unconsciousness, it seemed as if he had betaken himself on foot to some spot or other whither he could not discriminate. Unexpectedly he espied, in the opposite direction, two priests coming towards him: the one a Buddhist, the other a Taoist. As they advanced they kept up the conversation in which they were engaged. "Whither do you purpose taking the object you have brought away?" he heard the Taoist inquire. To this question the Buddhist replied with a smile: "Set your mind at ease," he said; "there's now in maturity a plot of a general character involving mundane pleasures, which will presently come to a denouement. The whole number of the votaries of voluptuousness have, as yet, not been quickened or entered the world, and I mean to avail myself of this occasion to introduce this object among their number, so as to give it a chance to go through the span of human existence." "The votaries of voluptuousness of these days will naturally have again to endure the ills of life during their course through the mortal world," the Taoist remarked; "but when, I wonder, will they spring into existence? and in what place will they descend?"

"The account of these circumstances," the bonze ventured to reply, "is enough to make you laugh! They amount to this: there existed in the west, on the bank of the Ling (spiritual) river, by the side of the San Sheng (thrice-born) stone, a blade of the Chiang Chu (purple pearl) grass. At about the same time it was that the block of stone was, consequent upon its rejection by the goddess of works, also left to ramble and wander to its own gratification, and to roam about at pleasure to every and any place. One day it came within the precincts of the Ching Huan (Monitory Vision) Fairy; and this Fairy, cognizant of the fact that this stone had a history, detained it, therefore, to reside at the Ch'ih Hsia (purple clouds) palace, and apportioned to it the duties of attendant on Shen Ying, a fairy of the Ch'ih Hsia palace.

"This stone would, however, often stroll along the banks of the Ling river, and having at the sight of the blade of spiritual grass been filled with admiration, it, day by day, moistened its roots with sweet dew. This purple pearl grass, at the outset, tarried for months and years; but being at a later period imbued with the essence and luxuriance of heaven and earth, and having incessantly received the moisture and nurture of the sweet dew, divested itself, in course of time, of the form of a grass; assuming, in lieu, a human nature, which gradually became perfected into the person of a girl.

"Every day she was wont to wander beyond the confines of the Li Hen (divested animosities) heavens. When hungry she fed on the Pi Ch'ing (hidden love) fruit--when thirsty she drank the Kuan ch'ou (discharged sorrows,) water. Having, however, up to this time, not shewn her gratitude for the virtue of nurture lavished upon her, the result was but natural that she should resolve in her heart upon a constant and incessant purpose to make suitable acknowledgment.

"I have been," she would often commune within herself, "the recipient of the gracious bounty of rain and dew, but I possess no such water as was lavished upon me to repay it! But should it ever descend into the world in the form of a human being, I will also betake myself thither, along with it; and if I can only have the means of making restitution to it, with the tears of a whole lifetime, I may be able to make adequate return."

"This resolution it is that will evolve the descent into the world of so many pleasure-bound spirits of retribution and the experience of fantastic destinies; and this crimson pearl blade will also be among the number. The stone still lies in its original place, and why should not you and I take it along before the tribunal of the Monitory Vision Fairy, and place on its behalf its name on record, so that it should descend into the world, in company with these spirits of passion, and bring this plot to an issue?"

"It is indeed ridiculous," interposed the Taoist. "Never before have I heard even the very mention of restitution by means of tears! Why should not you and I avail ourselves of this opportunity to likewise go down into the world? and if successful in effecting the salvation of a few of them, will it not be a work meritorious and virtuous?"

"This proposal," remarked the Buddhist, "is quite in harmony with my own views. Come along then with me to the palace of the Monitory Vision Fairy, and let us deliver up this good-for-nothing object, and have done with it! And when the company of pleasure-bound spirits of wrath descend into human existence, you and I can then enter the world. Half of them have already fallen into the dusty universe, but the whole number of them have not, as yet, come together."

"Such being the case," the Taoist acquiesced, "I am ready to follow you, whenever you please to go."

But to return to Chen Shih-yin. Having heard every one of these words distinctly, he could not refrain from forthwith stepping forward and paying homage. "My spiritual lords," he said, as he smiled, "accept my obeisance." The Buddhist and Taoist priests lost no time in responding to the compliment, and they exchanged the usual salutations. "My spiritual lords," Shih-yin continued; "I have just heard the conversation that passed between you, on causes and effects, a conversation the like of which few mortals have forsooth listened to; but your younger brother is sluggish of intellect, and cannot lucidly fathom the import! Yet could this dulness and simplicity be graciously dispelled, your younger brother may, by listening minutely, with undefiled ear and careful attention, to a certain degree be aroused to a sense of understanding; and what is more, possibly find the means of escaping the anguish of sinking down into Hades."

The two spirits smiled, "The conversation," they added, "refers to the primordial scheme and cannot be divulged before the proper season; but, when the time comes, mind do not forget us two, and you will readily be able to escape from the fiery furnace."

Shih-yin, after this reply, felt it difficult to make any further inquiries. "The primordial scheme," he however remarked smiling, "cannot, of course, be divulged; but what manner of thing, I wonder, is the good-for-nothing object you alluded to a short while back? May I not be allowed to judge for myself?"

"This object about which you ask," the Buddhist Bonze responded, "is intended, I may tell you, by fate to be just glanced at by you." With these words he produced it, and handed it over to Shih-yin.

Shih-yin received it. On scrutiny he found it, in fact, to be a beautiful gem, so lustrous and so clear that the traces of characters on the surface were distinctly visible. The characters inscribed consisted of the four "T'ung Ling Pao Yue," "Precious Gem of Spiritual Perception." On the obverse, were also several columns of minute words, which he was just in the act of looking at intently, when the Buddhist at once expostulated.

"We have already reached," he exclaimed, "the confines of vision." Snatching it violently out of his hands, he walked away with the Taoist, under a lofty stone portal, on the face of which appeared in large type the four characters: "T'ai Hsue Huan Ching," "The Visionary limits of the Great Void." On each side was a scroll with the lines:

When falsehood stands for truth, truth likewise becomes false, Where naught be made to aught, aught changes into naught.

Shih-yin meant also to follow them on the other side, but, as he was about to make one step forward, he suddenly heard a crash, just as if the mountains had fallen into ruins, and the earth sunk into destruction. As Shih-yin uttered a loud shout, he looked with strained eye; but all he could see was the fiery sun shining, with glowing rays, while the banana leaves drooped their heads. By that time, half of the circumstances connected with the dream he had had, had already slipped from his memory.

He also noticed a nurse coming towards him with Ying Lien in her arms. To Shih-yin's eyes his daughter appeared even more beautiful, such a bright gem, so precious, and so lovable. Forthwith stretching out his arms, he took her over, and, as he held her in his embrace, he coaxed her to play with him for a while; after which he brought her up to the street to see the great stir occasioned by the procession that was going past.

He was about to come in, when he caught sight of two priests, one a Taoist, the other a Buddhist, coming hither from the opposite direction. The Buddhist had a head covered with mange, and went barefooted. The Taoist had a limping foot, and his hair was all dishevelled.

Like maniacs, they jostled along, chattering and laughing as they drew near.

As soon as they reached Shih-yin's door, and they perceived him with Ying Lien in his arms, the Bonze began to weep aloud.

Turning towards Shih-yin, he said to him: "My good Sir, why need you carry in your embrace this living but luckless thing, which will involve father and mother in trouble?"

These words did not escape Shih-yin's ear; but persuaded that they amounted to raving talk, he paid no heed whatever to the bonze.

"Part with her and give her to me," the Buddhist still went on to say.

Shih-yin could not restrain his annoyance; and hastily pressing his daughter closer to him, he was intent upon going in, when the bonze pointed his hand at him, and burst out in a loud fit of laughter.

He then gave utterance to the four lines that follow:

You indulge your tender daughter and are laughed at as inane; Vain you face the snow, oh mirror! for it will evanescent wane, When the festival of lanterns is gone by, guard 'gainst your doom, 'Tis what time the flames will kindle, and the fire will consume.

Shih-yin understood distinctly the full import of what he heard; but his heart was still full of conjectures. He was about to inquire who and what they were, when he heard the Taoist remark,--"You and I cannot speed together; let us now part company, and each of us will be then able to go after his own business. After the lapse of three ages, I shall be at the Pei Mang mount, waiting for you; and we can, after our reunion, betake ourselves to the Visionary Confines of the Great Void, there to cancel the name of the stone from the records."

"Excellent! first rate!" exclaimed the Bonze. And at the conclusion of these words, the two men parted, each going his own way, and no trace was again seen of them.

"These two men," Shih-yin then pondered within his heart, "must have had many experiences, and I ought really to have made more inquiries of them; but at this juncture to indulge in regret is anyhow too late."

While Shih-yin gave way to these foolish reflections, he suddenly noticed the arrival of a penniless scholar, Chia by surname, Hua by name, Shih-fei by style and Yue-ts'un by nickname, who had taken up his quarters in the Gourd temple next door. This Chia Yue-ts'un was originally a denizen of Hu-Chow, and was also of literary and official parentage, but as he was born of the youngest stock, and the possessions of his paternal and maternal ancestors were completely exhausted, and his parents and relatives were dead, he remained the sole and only survivor; and, as he found his residence in his native place of no avail, he therefore entered the capital in search of that reputation, which would enable him to put the family estate on a proper standing. He had arrived at this place since the year before last, and had, what is more, lived all along in very straitened circumstances. He had made the temple his temporary quarters, and earned a living by daily occupying himself in composing documents and writing letters for customers. Thus it was that Shih-yin had been in constant relations with him.

As soon as Yue-ts'un perceived Shih-yin, he lost no time in saluting him. "My worthy Sir," he observed with a forced smile; "how is it you are leaning against the door and looking out? Is there perchance any news astir in the streets, or in the public places?"

"None whatever," replied Shih-yin, as he returned the smile. "Just a while back, my young daughter was in sobs, and I coaxed her out here to amuse her. I am just now without anything whatever to attend to, so that, dear brother Chia, you come just in the nick of time. Please walk into my mean abode, and let us endeavour, in each other's company, to while away this long summer day."

After he had made this remark, he bade a servant take his daughter in, while he, hand-in-hand with Yue-ts'un, walked into the library, where a young page served tea. They had hardly exchanged a few sentences, when one of the household came in, in flying haste, to announce that Mr. Yen had come to pay a visit.

Shih-yin at once stood up. "Pray excuse my rudeness," he remarked apologetically, "but do sit down; I shall shortly rejoin you, and enjoy the pleasure of your society." "My dear Sir," answered Yue-ts'un, as he got up, also in a conceding way, "suit your own convenience. I've often had the honour of being your guest, and what will it matter if I wait a little?" While these apologies were yet being spoken, Shih-yin had already walked out into the front parlour. During his absence, Yue-ts'un occupied himself in turning over the pages of some poetical work to dispel ennui, when suddenly he heard, outside the window, a woman's cough. Yue-ts'un hurriedly got up and looked out. He saw at a glance that it was a servant girl engaged in picking flowers. Her deportment was out of the common; her eyes so bright, her eyebrows so well defined. Though not a perfect beauty, she possessed nevertheless charms sufficient to arouse the feelings. Yue-ts'un unwittingly gazed at her with fixed eye. This waiting-maid, belonging to the Chen family, had done picking flowers, and was on the point of going in, when she of a sudden raised her eyes and became aware of the presence of some person inside the window, whose head-gear consisted of a turban in tatters, while his clothes were the worse for wear. But in spite of his poverty, he was naturally endowed with a round waist, a broad back, a fat face, a square mouth; added to this, his eyebrows were swordlike, his eyes resembled stars, his nose was straight, his cheeks square.

This servant girl turned away in a hurry and made her escape.

"This man so burly and strong," she communed within herself, "yet at the same time got up in such poor attire, must, I expect, be no one else than the man, whose name is Chia Yue-ts'un or such like, time after time referred to by my master, and to whom he has repeatedly wished to give a helping hand, but has failed to find a favourable opportunity. And as related to our family there is no connexion or friend in such straits, I feel certain it cannot be any other person than he. Strange to say, my master has further remarked that this man will, for a certainty, not always continue in such a state of destitution."

As she indulged in this train of thought, she could not restrain herself from turning her head round once or twice.

When Yue-ts'un perceived that she had looked back, he readily interpreted it as a sign that in her heart her thoughts had been of him, and he was frantic with irrepressible joy.

"This girl," he mused, "is, no doubt, keen-eyed and eminently shrewd, and one in this world who has seen through me."

The servant youth, after a short time, came into the room; and when Yue-ts'un made inquiries and found out from him that the guests in the front parlour had been detained to dinner, he could not very well wait any longer, and promptly walked away down a side passage and out of a back door.

When the guests had taken their leave, Shih-yin did not go back to rejoin Yue-ts'un, as he had come to know that he had already left.

In time the mid-autumn festivities drew near; and Shih-yin, after the family banquet was over, had a separate table laid in the library, and crossed over, in the moonlight, as far as the temple and invited Yue-ts'un to come round.

The fact is that Yue-ts'un, ever since the day on which he had seen the girl of the Chen family turn twice round to glance at him, flattered himself that she was friendly disposed towards him, and incessantly fostered fond thoughts of her in his heart. And on this day, which happened to be the mid-autumn feast, he could not, as he gazed at the moon, refrain from cherishing her remembrance. Hence it was that he gave vent to these pentameter verses:

Alas! not yet divined my lifelong wish, And anguish ceaseless comes upon anguish I came, and sad at heart, my brow I frowned; She went, and oft her head to look turned round. Facing the breeze, her shadow she doth watch, Who's meet this moonlight night with her to match? The lustrous rays if they my wish but read Would soon alight upon her beauteous head!

Yue-ts'un having, after this recitation, recalled again to mind how that throughout his lifetime his literary attainments had had an adverse fate and not met with an opportunity (of reaping distinction), went on to rub his brow, and as he raised his eyes to the skies, he heaved a deep sigh and once more intoned a couplet aloud:

The gem in the cask a high price it seeks, The pin in the case to take wing it waits.

As luck would have it, Shih-yin was at the moment approaching, and upon hearing the lines, he said with a smile: "My dear Yue-ts'un, really your attainments are of no ordinary capacity."

Yue-ts'un lost no time in smiling and replying. "It would be presumption in my part to think so," he observed. "I was simply at random humming a few verses composed by former writers, and what reason is there to laud me to such an excessive degree? To what, my dear Sir, do I owe the pleasure of your visit?" he went on to inquire. "Tonight," replied Shih-yin, "is the mid-autumn feast, generally known as the full-moon festival; and as I could not help thinking that living, as you my worthy brother are, as a mere stranger in this Buddhist temple, you could not but experience the feeling of loneliness. I have, for the express purpose, prepared a small entertainment, and will be pleased if you will come to my mean abode to have a glass of wine. But I wonder whether you will entertain favourably my modest invitation?" Yue-ts'un, after listening to the proposal, put forward no refusal of any sort; but remarked complacently: "Being the recipient of such marked attention, how can I presume to repel your generous consideration?"

As he gave expression to these words, he walked off there and then, in company with Shih-yin, and came over once again into the court in front of the library. In a few minutes, tea was over.

The cups and dishes had been laid from an early hour, and needless to say the wines were luscious; the fare sumptuous.

The two friends took their seats. At first they leisurely replenished their glasses, and quietly sipped their wine; but as, little by little, they entered into conversation, their good cheer grew more genial, and unawares the glasses began to fly round, and the cups to be exchanged.

At this very hour, in every house of the neighbourhood, sounded the fife and lute, while the inmates indulged in music and singing. Above head, the orb of the radiant moon shone with an all-pervading splendour, and with a steady lustrous light, while the two friends, as their exuberance increased, drained their cups dry so soon as they reached their lips.

Yue-ts'un, at this stage of the collation, was considerably under the influence of wine, and the vehemence of his high spirits was irrepressible. As he gazed at the moon, he fostered thoughts, to which he gave vent by the recital of a double couplet.

'Tis what time three meets five, Selene is a globe! Her pure rays fill the court, the jadelike rails enrobe! Lo! in the heavens her disk to view doth now arise, And in the earth below to gaze men lift their eyes.

"Excellent!" cried Shih-yin with a loud voice, after he had heard these lines; "I have repeatedly maintained that it was impossible for you to remain long inferior to any, and now the verses you have recited are a prognostic of your rapid advancement. Already it is evident that, before long, you will extend your footsteps far above the clouds! I must congratulate you! I must congratulate you! Let me, with my own hands, pour a glass of wine to pay you my compliments."

Yue-ts'un drained the cup. "What I am about to say," he explained as he suddenly heaved a sigh, "is not the maudlin talk of a man under the effects of wine. As far as the subjects at present set in the examinations go, I could, perchance, also have well been able to enter the list, and to send in my name as a candidate; but I have, just now, no means whatever to make provision for luggage and for travelling expenses. The distance too to Shen Ching is a long one, and I could not depend upon the sale of papers or the composition of essays to find the means of getting there."

Shih-yin gave him no time to conclude. "Why did you not speak about this sooner?" he interposed with haste. "I have long entertained this suspicion; but as, whenever I met you, this conversation was never broached, I did not presume to make myself officious. But if such be the state of affairs just now, I lack, I admit, literary qualification, but on the two subjects of friendly spirit and pecuniary means, I have, nevertheless, some experience. Moreover, I rejoice that next year is just the season for the triennial examinations, and you should start for the capital with all despatch; and in the tripos next spring, you will, by carrying the prize, be able to do justice to the proficiency you can boast of. As regards the travelling expenses and the other items, the provision of everything necessary for you by my own self will again not render nugatory your mean acquaintance with me."

Forthwith, he directed a servant lad to go and pack up at once fifty taels of pure silver and two suits of winter clothes.

"The nineteenth," he continued, "is a propitious day, and you should lose no time in hiring a boat and starting on your journey westwards. And when, by your eminent talents, you shall have soared high to a lofty position, and we meet again next winter, will not the occasion be extremely felicitous?"

Yue-ts'un accepted the money and clothes with but scanty expression of gratitude. In fact, he paid no thought whatever to the gifts, but went on, again drinking his wine, as he chattered and laughed.

It was only when the third watch of that day had already struck that the two friends parted company; and Shih-yin, after seeing Yue-ts'un off, retired to his room and slept, with one sleep all through, never waking until the sun was well up in the skies.

Remembering the occurrence of the previous night, he meant to write a couple of letters of recommendation for Yue-ts'un to take along with him to the capital, to enable him, after handing them over at the mansions of certain officials, to find some place as a temporary home. He accordingly despatched a servant to ask him to come round, but the man returned and reported that from what the bonze said, "Mr. Chia had started on his journey to the capital, at the fifth watch of that very morning, that he had also left a message with the bonze to deliver to you, Sir, to the effect that men of letters paid no heed to lucky or unlucky days, that the sole consideration with them was the nature of the matter in hand, and that he could find no time to come round in person and bid good-bye."

Shih-yin after hearing this message had no alternative but to banish the subject from his thoughts.

In comfortable circumstances, time indeed goes by with easy stride. Soon drew near also the happy festival of the 15th of the 1st moon, and Shih-yin told a servant Huo Ch'i to take Ying Lien to see the sacrificial fires and flowery lanterns.

About the middle of the night, Huo Ch'i was hard pressed, and he forthwith set Ying Lien down on the doorstep of a certain house. When he felt relieved, he came back to take her up, but failed to find anywhere any trace of Ying Lien. In a terrible plight, Huo Ch'i prosecuted his search throughout half the night; but even by the dawn of day, he had not discovered any clue of her whereabouts. Huo Ch'i, lacking, on the other hand, the courage to go back and face his master, promptly made his escape to his native village.

Shih-yin--in fact, the husband as well as the wife--seeing that their child had not come home during the whole night, readily concluded that some mishap must have befallen her. Hastily they despatched several servants to go in search of her, but one and all returned to report that there was neither vestige nor tidings of her.

This couple had only had this child, and this at the meridian of their life, so that her sudden disappearance plunged them in such great distress that day and night they mourned her loss to such a point as to well nigh pay no heed to their very lives.

A month in no time went by. Shih-yin was the first to fall ill, and his wife, Dame Feng, likewise, by dint of fretting for her daughter, was also prostrated with sickness. The doctor was, day after day, sent for, and the oracle consulted by means of divination.

Little did any one think that on this day, being the 15th of the 3rd moon, while the sacrificial oblations were being prepared in the Hu Lu temple, a pan with oil would have caught fire, through the want of care on the part of the bonze, and that in a short time the flames would have consumed the paper pasted on the windows.

Among the natives of this district bamboo fences and wooden partitions were in general use, and these too proved a source of calamity so ordained by fate (to consummate this decree).

With promptness (the fire) extended to two buildings, then enveloped three, then dragged four (into ruin), and then spread to five houses, until the whole street was in a blaze, resembling the flames of a volcano. Though both the military and the people at once ran to the rescue, the fire had already assumed a serious hold, so that it was impossible for them to afford any effective assistance for its suppression.

It blazed away straight through the night, before it was extinguished, and consumed, there is in fact no saying how many dwelling houses. Anyhow, pitiful to relate, the Chen house, situated as it was next door to the temple, was, at an early part of the evening, reduced to a heap of tiles and bricks; and nothing but the lives of that couple and several inmates of the family did not sustain any injuries.

Shih-yin was in despair, but all he could do was to stamp his feet and heave deep sighs. After consulting with his wife, they betook themselves to a farm of theirs, where they took up their quarters temporarily. But as it happened that water had of late years been scarce, and no crops been reaped, robbers and thieves had sprung up like bees, and though the Government troops were bent upon their capture, it was anyhow difficult to settle down quietly on the farm. He therefore had no other resource than to convert, at a loss, the whole of his property into money, and to take his wife and two servant girls and come over for shelter to the house of his father-in-law.

His father-in-law, Feng Su, by name, was a native of Ta Ju Chou. Although only a labourer, he was nevertheless in easy circumstances at home. When he on this occasion saw his son-in-law come to him in such distress, he forthwith felt at heart considerable displeasure. Fortunately Shih-yin had still in his possession the money derived from the unprofitable realization of his property, so that he produced and handed it to his father-in-law, commissioning him to purchase, whenever a suitable opportunity presented itself, a house and land as a provision for food and raiment against days to come. This Feng Su, however, only expended the half of the sum, and pocketed the other half, merely acquiring for him some fallow land and a dilapidated house.

Shih-yin being, on the other hand, a man of books and with no experience in matters connected with business and with sowing and reaping, subsisted, by hook and by crook, for about a year or two, when he became more impoverished.

In his presence, Feng Su would readily give vent to specious utterances, while, with others, and behind his back, he on the contrary expressed his indignation against his improvidence in his mode of living, and against his sole delight of eating and playing the lazy.

Shih-yin, aware of the want of harmony with his father-in-law, could not help giving way, in his own heart, to feelings of regret and pain. In addition to this, the fright and vexation which he had undergone the year before, the anguish and suffering (he had had to endure), had already worked havoc (on his constitution); and being a man advanced in years, and assailed by the joint attack of poverty and disease, he at length gradually began to display symptoms of decline.

Strange coincidence, as he, on this day, came leaning on his staff and with considerable strain, as far as the street for a little relaxation, he suddenly caught sight, approaching from the off side, of a Taoist priest with a crippled foot; his maniac appearance so repulsive, his shoes of straw, his dress all in tatters, muttering several sentiments to this effect:

All men spiritual life know to be good, But fame to disregard they ne'er succeed! From old till now the statesmen where are they? Waste lie their graves, a heap of grass, extinct. All men spiritual life know to be good, But to forget gold, silver, ill succeed! Through life they grudge their hoardings to be scant, And when plenty has come, their eyelids close. All men spiritual life hold to be good, Yet to forget wives, maids, they ne'er succeed! Who speak of grateful love while lives their lord, And dead their lord, another they pursue. All men spiritual life know to be good, But sons and grandsons to forget never succeed! From old till now of parents soft many, But filial sons and grandsons who have seen?

Shih-yin upon hearing these words, hastily came up to the priest, "What were you so glibly holding forth?" he inquired. "All I could hear were a lot of hao liao (excellent, finality.")

"You may well have heard the two words 'hao liao,'" answered the Taoist with a smile, "but can you be said to have fathomed their meaning? You should know that all things in this world are excellent, when they have attained finality; when they have attained finality, they are excellent; but when they have not attained finality, they are not excellent; if they would be excellent, they should attain finality. My song is entitled Excellent-finality (hao liao)."

Shih-yin was gifted with a natural perspicacity that enabled him, as soon as he heard these remarks, to grasp their spirit.

"Wait a while," he therefore said smilingly; "let me unravel this excellent-finality song of yours; do you mind?"

"Please by all means go on with the interpretation," urged the Taoist; whereupon Shih-yin proceeded in this strain:

Sordid rooms and vacant courts, Replete in years gone by with beds where statesmen lay; Parched grass and withered banian trees, Where once were halls for song and dance! Spiders' webs the carved pillars intertwine, The green gauze now is also pasted on the straw windows! What about the cosmetic fresh concocted or the powder just scented; Why has the hair too on each temple become white like hoarfrost! Yesterday the tumulus of yellow earth buried the bleached bones, To-night under the red silk curtain reclines the couple! Gold fills the coffers, silver fills the boxes, But in a twinkle, the beggars will all abuse you! While you deplore that the life of others is not long, You forget that you yourself are approaching death! You educate your sons with all propriety, But they may some day, 'tis hard to say become thieves; Though you choose (your fare and home) the fatted beam, You may, who can say, fall into some place of easy virtue! Through your dislike of the gauze hat as mean, You have come to be locked in a cangue; Yesterday, poor fellow, you felt cold in a tattered coat, To-day, you despise the purple embroidered dress as long! Confusion reigns far and wide! you have just sung your part, I come on the boards, Instead of yours, you recognise another as your native land; What utter perversion! In one word, it comes to this we make wedding clothes for others! (We sow for others to reap.)

The crazy limping Taoist clapped his hands. "Your interpretation is explicit," he remarked with a hearty laugh, "your interpretation is explicit!"

Shih-yin promptly said nothing more than,--"Walk on;" and seizing the stole from the Taoist's shoulder, he flung it over his own. He did not, however, return home, but leisurely walked away, in company with the eccentric priest.

The report of his disappearance was at once bruited abroad, and plunged the whole neighbourhood in commotion; and converted into a piece of news, it was circulated from mouth to mouth.

Dame Feng, Shih-yin's wife, upon hearing the tidings, had such a fit of weeping that she hung between life and death; but her only alternative was to consult with her father, and to despatch servants on all sides to institute inquiries. No news was however received of him, and she had nothing else to do but to practise resignation, and to remain dependent upon the support of her parents for her subsistence. She had fortunately still by her side, to wait upon her, two servant girls, who had been with her in days gone by; and the three of them, mistress as well as servants, occupied themselves day and night with needlework, to assist her father in his daily expenses.

This Feng Su had after all, in spite of his daily murmurings against his bad luck, no help but to submit to the inevitable.

On a certain day, the elder servant girl of the Chen family was at the door purchasing thread, and while there, she of a sudden heard in the street shouts of runners clearing the way, and every one explain that the new magistrate had come to take up his office.

The girl, as she peeped out from inside the door, perceived the lictors and policemen go by two by two; and when unexpectedly in a state chair, was carried past an official, in black hat and red coat, she was indeed quite taken aback.

"The face of this officer would seem familiar," she argued within herself; "just as if I had seen him somewhere or other ere this."

Shortly she entered the house, and banishing at once the occurrence from her mind, she did not give it a second thought. At night, however, while she was waiting to go to bed, she suddenly heard a sound like a rap at the door. A band of men boisterously cried out: "We are messengers, deputed by the worthy magistrate of this district, and come to summon one of you to an enquiry."

Feng Su, upon hearing these words, fell into such a terrible consternation that his eyes stared wide and his mouth gaped.

What calamity was impending is not as yet ascertained, but, reader, listen to the explanation contained in the next chapter.

此回中凡用“梦”用“幻”等字,是提醒阅者眼目,亦是此书立意本旨。

列位看官:你道此书从何而来?说起根由虽近荒唐,细按则深有趣味。待在下将此来历注明,方使阅者了然不惑。

原来女娲氏炼石补天之时,于大荒山无稽崖练成高经十二丈,方经二十四丈顽石三万六千五百零一块。娲皇氏只用了三万六千五百块,只单单剩了一块未用,便弃在此山青埂峰下。谁知此石自经煅炼之后,灵性已通,因见众石俱得补天,独自己无材不堪入选,遂自怨自叹,日夜悲号惭愧。

一日,正当嗟悼之际,俄见一僧一道远远而来,生得骨骼不凡,丰神迥异,说说笑笑来至峰下,坐于石边高谈快论。先是说些云山雾海神仙玄幻之事,后便说到红尘中荣华富贵。此石听了,不觉打动凡心,也想要到人间去享一享这荣华富贵,但自恨粗蠢,不得已,便口吐人言,向那僧道说道:“大师,弟子蠢物,不能见礼了。适闻二位谈那人世间荣耀繁华,心切慕之。弟子质虽粗蠢,性却稍通,况见二师仙形道体,定非凡品,必有补天济世之材,利物济人之德。如蒙发一点慈心,携带弟子得入红尘,在那富贵场中,温柔乡里受享几年,自当永佩洪恩,万劫不忘也。”二仙师听毕,齐憨笑道:“善哉,善哉!那红尘中有却有些乐事,但不能永远依恃,况又有‘美中不足,好事多魔’八个字紧相连属,瞬息间则又乐极悲生,人非物换,究竟是到头一梦,万境归空,倒不如不去的好。”这石凡心已炽,那里听得进这话去,乃复苦求再四。二仙知不可强制,乃叹道:“此亦静极怂级*,无中生有之数也。既如此,我们便携你去受享受享,只是到不得意时,切莫后悔。”石道:“自然,自然。”那僧又道:“若说你性灵,却又如此质蠢,并更无奇贵之处。如此也只好踮脚而已。也罢,我如今大施佛法助你助,待劫终之日,复还本质,以了此案。你道好否?"石头听了,感谢不尽。那僧便念咒书符,大展幻术,将一块大石登时变成一块鲜明莹洁的美玉,且又缩成扇坠大小的可佩可拿。那僧托于掌上,笑道:“形体倒也是个宝物了!还只没有,实在的好处,须得再镌上数字,使人一见便知是奇物方妙。然后携你到那昌明隆盛之邦,诗礼簪缨之族,花柳繁华地,温柔富贵乡去安身乐业。”石头听了,喜不能禁,乃问:“不知赐了弟子那几件奇处,又不知携了弟子到何地方?望乞明示,使弟子不惑。”那僧笑道:“你且莫问,日后自然明白的。”说着,便袖了这石,同那道人飘然而去,竟不知投奔何方何舍。

后来,又不知过了几世几劫,因有个空空道人访道求仙,忽从这大荒山无稽崖青埂峰下经过,忽见一大块石上字迹分明,编述历历。空空道人乃从头一看,原来就是无材补天,幻形入世,蒙茫茫大士,渺渺真人携入红尘,历尽离合悲欢炎凉世态的一段故事。后面又有一首偈云:

无材可去补苍天,枉入红尘若许年。

此系身前身后事,倩谁记去作奇传?诗后便是此石坠落之乡,投胎之处,亲自经历的一段陈迹故事。其中家庭闺阁琐事,以及闲情诗词倒还全备,或可适趣解闷,然朝代年纪,地舆邦国,却反失落无考。

空空道人遂向石头说道:“石兄,你这一段故事,据你自己说有些趣味,故编写在此,意欲问世传奇。据我看来,第一件,无朝代年纪可考,第二件,并无大贤大忠理朝廷治风俗的善政,其中只不过几个异样女子,或情或痴,或小才微善,亦无班姑,蔡女之德能。我纵抄去,恐世人不爱看呢。”石头笑答道:“我师何太痴耶!若云无朝代可考,今我师竟假借汉唐等年纪添缀,又有何难?但我想,历来野史,皆蹈一辙,莫如我这不借此套者,反倒新奇别致,不过只取其事体情理罢了,又何必拘拘于朝代年纪哉!再者,市井俗人喜看理治之书者甚少,爱适趣闲文者特多。历来野史,或讪谤君相,或贬人妻女,奸淫凶恶,不可胜数。更有一种风月笔墨,其淫秽污臭,屠毒笔墨,坏人子弟,又不可胜数。至若佳人才子等书,则又千部共出一套,且其中终不能不涉于淫滥,以致满纸潘安,子建,西子,文君,不过作者要写出自己的那两首情诗艳赋来,故假拟出男女二人名姓,又必旁出一小人其间拨乱,亦如剧中之小丑然。且鬟婢开口即者也之乎,非文即理。故逐一看去,悉皆自相矛盾,大不近情理之话,竟不如我半世亲睹亲闻的这几个女子,虽不敢说强似前代书中所有之人,但事迹原委,亦可以消愁破闷,也有几首歪诗熟话,可以喷饭供酒。至若离合悲欢,兴衰际遇,则又追踪蹑迹,不敢稍加穿凿,徒为供人之目而反失其真传者。今之人,贫者日为衣食所累,富者又怀不足之心,纵然一时稍闲,又有贪淫恋色,好货寻愁之事,那里去有工夫看那理治之书?所以我这一段故事,也不愿世人称奇道妙,也不定要世人喜悦检读,只愿他们当那醉淫饱卧之时,或避世去愁之际,把此一玩,岂不省了些寿命筋力?就比那谋虚逐妄,却也省了口舌是非之害,腿脚奔忙之苦。再者,亦令世人换新眼目,不比那些胡牵乱扯,忽离忽遇,满纸才人淑女,子建文君红娘小玉等通共熟套之旧稿。我师意为何如?”

空空道人听如此说,思忖半晌,将《石头记》再检阅一遍,因见上面虽有些指奸责佞贬恶诛邪之语,亦非伤时骂世之旨,及至君仁臣良父慈子孝,凡伦常所关之处,皆是称功颂德,眷眷无穷,实非别书之可比。虽其中大旨谈情,亦不过实录其事,又非假拟妄称,一味淫邀艳约,私订偷盟之可比。因毫不干涉时世,方从头至尾抄录回来,问世传奇。从此空空道人因空见色,由色生情,传情入色,自色悟空,遂易名为情僧,改《石头记》为《情僧录》。东鲁孔梅溪则题曰《风月宝鉴》。后因曹雪芹于悼红轩中披阅十载,增删五次,纂成目录,分出章回,则题曰《金陵十二钗》。并题一绝云:

满纸荒唐言,一把辛酸泪!

都云作者痴,谁解其中味?

出则既明,且看石上是何故事。按那石上书云:

当日地陷东南,这东南一隅有处曰姑苏,有城曰阊门者,最是红尘中一二等富贵风流之地。这阊门外有个十里街,街内有个仁清巷,巷内有个古庙,因地方窄狭,人皆呼作葫芦庙。庙旁住着一家乡宦,姓甄,名费,字士隐。嫡妻封氏,情性贤淑,深明礼义。家中虽不甚富贵,然本地便也推他为望族了。因这甄士隐禀性恬淡,不以功名为念,每日只以观花修竹,酌酒吟诗为乐,倒是神仙一流人品。只是一件不足:如今年已半百,膝下无儿,只有一女,乳名唤作英莲,年方三岁。

一日,炎夏永昼,士隐于书房闲坐,至手倦抛书,伏几少憩,不觉朦胧睡去。梦至一处,不辨是何地方。忽见那厢来了一僧一道,且行且谈。只听道人问道:“你携了这蠢物,意欲何往?"那僧笑道:“你放心,如今现有一段风流公案正该了结,这一干风流冤家,尚未投胎入世。趁此机会,就将此蠢物夹带于中,使他去经历经历。”那道人道:“原来近日风流冤孽又将造劫历世去不成?但不知落于何方何处?"那僧笑道:“此事说来好笑,竟是千古未闻的罕事。只因西方灵河岸上三生石畔,有绛珠草一株,时有赤瑕宫神瑛侍者,日以甘露灌溉,这绛珠草始得久延岁月。后来既受天地精华,复得雨露滋养,遂得脱却草胎木质,得换人形,仅修成个女体,终日游于离恨天外,饥则食蜜青果为膳,渴则饮灌愁海水为汤。只因尚未酬报灌溉之德,故其五内便郁结着一段缠绵不尽之意。恰近日这神瑛侍者凡心偶炽,乘此昌明太平朝世,意欲下凡造历幻缘,已在警幻仙子案前挂了号。警幻亦曾问及,灌溉之情未偿,趁此倒可了结的。那绛珠仙子道:‘他是甘露之惠,我并无此水可还。他既下世为人,我也去下世为人,但把我一生所有的眼泪还他,也偿还得过他了。’因此一事,就勾出多少风流冤家来,陪他们去了结此案。”那道人道:“果是罕闻。实未闻有还泪之说。想来这一段故事,比历来风月事故更加琐碎细腻了。”那僧道:“历来几个风流人物,不过传其大概以及诗词篇章而已,至家庭闺阁中一饮一食,总未述记。再者,大半风月故事,不过偷香窃玉,暗约私奔而已,并不曾将儿女之真情发泄一二。想这一干人入世,其情痴色鬼,贤愚不肖者,悉与前人传述不同矣。”那道人道:“趁此何不你我也去下世度脱几个,岂不是一场功德?"那僧道:“正合吾意,你且同我到警幻仙子宫中,将蠢物交割清楚,待这一干风流孽鬼下世已完,你我再去。如今虽已有一半落尘,然犹未全集。”道人道:“既如此,便随你去来。”

却说甄士隐俱听得明白,但不知所云"蠢物"系何东西。遂不禁上前施礼,笑问道:“二仙师请了。”那僧道也忙答礼相问。士隐因说道:“适闻仙师所谈因果,实人世罕闻者。但弟子愚浊,不能洞悉明白,若蒙大开痴顽,备细一闻,弟子则洗耳谛听,稍能警省,亦可免沉伦之苦。”二仙笑道:“此乃玄机不可预泄者。到那时不要忘我二人,便可跳出火坑矣。”士隐听了,不便再问。因笑道:“玄机不可预泄,但适云‘蠢物’,不知为何,或可一见否?"那僧道:“若问此物,倒有一面之缘。”说着,取出递与士隐。士隐接了看时,原来是块鲜明美玉,上面字迹分明,镌着"通灵宝玉"四字,后面还有几行小字。正欲细看时,那僧便说已到幻境,便强从手中夺了去,与道人竟过一大石牌坊,上书四个大字,乃是"太虚幻境"。两边又有一幅对联,道是:

假作真时真亦假,无为有处有还无。士隐意欲也跟了过去,方举步时,忽听一声霹雳,有若山崩地陷。士隐大叫一声,定睛一看,只见烈日炎炎,芭蕉冉冉,所梦之事便忘了大半。又见奶母正抱了英莲走来。士隐见女儿越发生得粉妆玉琢,乖觉可喜,便伸手接来,抱在怀内,斗他顽耍一回,又带至街前,看那过会的热闹。方欲进来时,只见从那边来了一僧一道:那僧则癞头跣脚,那道则跛足蓬头,疯疯癫癫,挥霍谈笑而至。及至到了他门前,看见士隐抱着英莲,那僧便大哭起来,又向士隐道:“施主,你把这有命无运,累及爹娘之物,抱在怀内作甚?"士隐听了,知是疯话,也不去睬他。那僧还说:“舍我罢,舍我罢!"士隐不耐烦,便抱女儿撤身要进去,那僧乃指着他大笑,口内念了四句言词道:

惯养娇生笑你痴,菱花空对雪澌澌。

好防佳节元宵后,便是烟消火灭时。士隐听得明白,心下犹豫,意欲问他们来历。只听道人说道:“你我不必同行,就此分手,各干营生去罢。三劫后,我在北邙山等你,会齐了同往太虚幻境销号。”那僧道:“最妙,最妙!"说毕,二人一去,再不见个踪影了。士隐心中此时自忖:这两个人必有来历,该试一问,如今悔却晚也。

这士隐正痴想,忽见隔壁葫芦庙内寄居的一个穷儒-姓贾名化,表字时飞,别号雨村者走了出来。这贾雨村原系胡州人氏,也是诗书仕宦之族,因他生于末世,父母祖宗根基已尽,人口衰丧,只剩得他一身一口,在家乡无益,因进京求取功名,再整基业。自前岁来此,又淹蹇住了,暂寄庙中安身,每日卖字作文为生,故士隐常与他交接。当下雨村见了士隐,忙施礼陪笑道:“老先生倚门伫望,敢是街市上有甚新闻否?"士隐笑道:“非也。适因小女啼哭,引他出来作耍,正是无聊之甚,兄来得正妙,请入小斋一谈,彼此皆可消此永昼。”说着,便令人送女儿进去,自与雨村携手来至书房中。小童献茶。方谈得三五句话,忽家人飞报:“严老爷来拜。”士隐慌的忙起身谢罪道:“恕诳驾之罪,略坐,弟即来陪。”雨村忙起身亦让道:“老先生请便。晚生乃常造之客,稍候何妨。”说着,士隐已出前厅去了。

这里雨村且翻弄书籍解闷。忽听得窗外有女子嗽声,雨村遂起身往窗外一看,原来是一个丫鬟,在那里撷花,生得仪容不俗,眉目清明,虽无十分姿色,却亦有动人之处。雨村不觉看的呆了。那甄家丫鬟撷了花,方欲走时,猛抬头见窗内有人,敝巾旧服,虽是贫窘,然生得腰圆背厚,面阔口方,更兼剑眉星眼,直鼻权腮。这丫鬟忙转身回避,心下乃想:“这人生的这样雄壮,却又这样褴褛,想他定是我家主人常说的什么贾雨村了,每有意帮助周济,只是没甚机会。我家并无这样贫窘亲友,想定是此人无疑了。怪道又说他必非久困之人。”如此想来,不免又回头两次。雨村见他回了头,便自为这女子心中有意于他,便狂喜不尽,自为此女子必是个巨眼英雄,风尘中之知己也。一时小童进来,雨村打听得前面留饭,不可久待,遂从夹道中自便出门去了。士隐待客既散,知雨村自便,也不去再邀。

一日,早又中秋佳节。士隐家宴已毕,乃又另具一席于书房,却自己步月至庙中来邀雨村。原来雨村自那日见了甄家之婢曾回顾他两次,自为是个知己,便时刻放在心上。今又正值中秋,不免对月有怀,因而口占五言一律云:

未卜三生愿,频添一段愁。

闷来时敛额,行去几回头。

自顾风前影,谁堪月下俦?

蟾光如有意,先上玉人楼。

雨村吟罢,因又思及平生抱负,苦未逢时,乃又搔首对天长叹,复高吟一联曰:

玉在匣中求善价,钗于奁内待时飞。

恰值士隐走来听见,笑道:“雨村兄真抱负不浅也!"雨村忙笑道:“不过偶吟前人之句,何敢狂诞至此。”因问:“老先生何兴至此?"士隐笑道:“今夜中秋,俗谓‘团圆之节’,想尊兄旅寄僧房,不无寂寥之感,故特具小酌,邀兄到敝斋一饮,不知可纳芹意否?"雨村听了,并不推辞,便笑道:“既蒙厚爱,何敢拂此盛情。”说着,便同士隐复过这边书院中来。须臾茶毕,早已设下杯盘,那美酒佳肴自不必说。二人归坐,先是款斟漫饮,次渐谈至兴浓,不觉飞觥限起来。当时街坊上家家箫管,户户弦歌,当头一轮明月,飞彩凝辉,二人愈添豪兴,酒到杯干。雨村此时已有七八分酒意,狂兴不禁,乃对月寓怀,口号一绝云:

时逢三五便团圆,满把晴光护玉栏。

天上一轮才捧出,人间万姓仰头看。士隐听了,大叫:“妙哉!吾每谓兄必非久居人下者,今所吟之句,飞腾之兆已见,不日可接履于云霓之上矣。可贺,可贺!"乃亲斟一斗为贺。雨村因干过,叹道:“非晚生酒后狂言,若论时尚之学,晚生也或可去充数沽名,只是目今行囊路费一概无措,神京路远,非赖卖字撰文即能到者。”士隐不待说完,便道:“兄何不早言。愚每有此心,但每遇兄时,兄并未谈及,愚故未敢唐突。今既及此,愚虽不才,‘义利’二字却还识得。且喜明岁正当大比,兄宜作速入都,春闱一战,方不负兄之所学也。其盘费余事,弟自代为处置,亦不枉兄之谬识矣!"当下即命小童进去,速封五十两白银,并两套冬衣。又云:“十九日乃黄道之期,兄可即买舟西上,待雄飞高举,明冬再晤,岂非大快之事耶!"雨村收了银衣,不过略谢一语,并不介意,仍是吃酒谈笑。那天已交了三更,二人方散。士隐送雨村去后,回房一觉,直至红日三竿方醒。因思昨夜之事,意欲再写两封荐书与雨村带至神都,使雨村投谒个仕宦之家为寄足之地。因使人过去请时,那家人去了回来说:“和尚说,贾爷今日五鼓已进京去了,也曾留下话与和尚转达老爷,说‘读书人不在黄道黑道,总以事理为要,不及面辞了。’"士隐听了,也只得罢了。真是闲处光阴易过,倏忽又是元霄佳节矣。士隐命家人霍启抱了英莲去看社火花灯,半夜中,霍启因要小解,便将英莲放在一家门槛上坐着。待他小解完了来抱时,那有英莲的踪影?急得霍启直寻了半夜,至天明不见,那霍启也就不敢回来见主人,便逃往他乡去了。那士隐夫妇,见女儿一夜不归,便知有些不妥,再使几人去寻找,回来皆云连音响皆无。夫妻二人,半世只生此女,一旦失落,岂不思想,因此昼夜啼哭,几乎不曾寻死。看看的一月,士隐先就得了一病,当时封氏孺人也因思女构疾,日日请医疗治。

不想这日三月十五,葫芦庙中炸供,那些和尚不加小心,致使油锅火逸,便烧着窗纸。此方人家多用竹篱木壁者,大抵也因劫数,于是接二连三,牵五挂四,将一条街烧得如火焰山一般。彼时虽有军民来救,那火已成了势,如何救得下?直烧了一夜,方渐渐的熄去,也不知烧了几家。只可怜甄家在隔壁,早已烧成一片瓦砾场了。只有他夫妇并几个家人的性命不曾伤了。急得士隐惟跌足长叹而已。只得与妻子商议,且到田庄上去安身。偏值近年水旱不收,鼠盗蜂起,无非抢田夺地,鼠窃狗偷,民不安生,因此官兵剿捕,难以安身。士隐只得将田庄都折变了,便携了妻子与两个丫鬟投他岳丈家去。

他岳丈名唤封肃,本贯大如州人氏,虽是务农,家中都还殷实。今见女婿这等狼狈而来,心中便有些不乐。幸而士隐还有折变田地的银子未曾用完,拿出来托他随分就价薄置些须房地,为后日衣食之计。那封肃便半哄半赚,些须与他些薄田朽屋。士隐乃读书之人,不惯生理稼穑等事,勉强支持了一二年,越觉穷了下去。封肃每见面时,便说些现成话,且人前人后又怨他们不善过活,只一味好吃懒作等语。士隐知投人不着,心中未免悔恨,再兼上年惊唬,急忿怨痛,已有积伤,暮年之人,贫病交攻,竟渐渐的露出那下世的光景来。

可巧这日拄了拐杖挣挫到街前散散心时,忽见那边来了一个跛足道人,疯癫落脱,麻屣鹑衣,口内念着几句言词,道是:

世人都晓神仙好,惟有功名忘不了!

古今将相在何方?荒冢一堆草没了。

世人都晓神仙好,只有金银忘不了!

终朝只恨聚无多,及到多时眼闭了。

世人都晓神仙好,只有姣妻忘不了!

君生日日说恩情,君死又随人去了。

世人都晓神仙好,只有儿孙忘不了!

痴心父母古来多,孝顺儿孙谁见了?

士隐听了,便迎上来道:“你满口说些什么?只听见些‘好’‘了’‘好’‘了’。那道人笑道:“你若果听见‘好’‘了’二字,还算你明白。可知世上万般,好便是了,了便是好。若不了,便不好,若要好,须是了。我这歌儿,便名《好了歌》"士隐本是有宿慧的,一闻此言,心中早已彻悟。因笑道:“且住!待我将你这《好了歌》解注出来何如?"道人笑道:“你解,你解。”士隐乃说道:

陋室空堂,当年笏满床,衰草枯杨,曾为歌舞场。蛛丝儿结满雕梁,绿纱今又糊在蓬窗上。说什么脂正浓、粉正香,如何两鬓又成霜?昨日黄土陇头送白骨,今宵红灯帐底卧鸳鸯。金满箱,银满箱,展眼乞丐人皆谤。正叹他人命不长,那知自己归来丧!训有方,保不定日后作强梁。择膏粱,谁承望流落在烟花巷!因嫌纱帽小,致使锁枷杠,昨怜破袄寒,今嫌紫蟒长:乱烘烘你方唱罢我登场,反认他乡是故乡。甚荒唐,到头来都是为他人作嫁衣裳!

那疯跛道人听了,拍掌笑道:“解得切,解得切!"士隐便说一声"走罢!"将道人肩上褡裢抢了过来背着,竟不回家,同了疯道人飘飘而去。当下烘动街坊,众人当作一件新闻传说。封氏闻得此信,哭个死去活来,只得与父亲商议,遣人各处访寻,那讨音信?无奈何,少不得依靠着他父母度日。幸而身边还有两个旧日的丫鬟伏侍,主仆三人,日夜作些针线发卖,帮着父亲用度。那封肃虽然日日抱怨,也无可奈何了。

这日,那甄家大丫鬟在门前买线,忽听街上喝道之声,众人都说新太爷到任。丫鬟于是隐在门内看时,只见军牢快手,一对一对的过去,俄而大轿抬着一个乌帽猩袍的官府过去。丫鬟倒发了个怔,自思这官好面善,倒象在那里见过的。于是进入房中,也就丢过不在心上。至晚间,正待歇息之时,忽听一片声打的门响,许多人乱嚷,说:“本府太爷差人来传人问话。”封肃听了,唬得目瞪口呆,不知有何祸事。

This is the opening section; this the first chapter. Subsequent to the visions of a dream which he had, on some previous occasion, experienced, the writer personally relates, he designedly concealed the true circumstances, and borrowed the attributes of perception and spirituality to relate this story of the Record of the Stone. With this purpose, he made use of such designations as Chen Shih-yin (truth under the garb of fiction) and the like. What are, however, the events recorded in this work? Who are the dramatis personae?

Wearied with the drudgery experienced of late in the world, the author speaking for himself, goes on to explain, with the lack of success which attended every single concern, I suddenly bethought myself of the womankind of past ages. Passing one by one under a minute scrutiny, I felt that in action and in lore, one and all were far above me; that in spite of the majesty of my manliness, I could not, in point of fact, compare with these characters of the gentle sex. And my shame forsooth then knew no bounds; while regret, on the other hand, was of no avail, as there was not even a remote possibility of a day of remedy.

On this very day it was that I became desirous to compile, in a connected form, for publication throughout the world, with a view to (universal) information, how that I bear inexorable and manifold retribution; inasmuch as what time, by the sustenance of the benevolence of Heaven, and the virtue of my ancestors, my apparel was rich and fine, and as what days my fare was savory and sumptuous, I disregarded the bounty of education and nurture of father and mother, and paid no heed to the virtue of precept and injunction of teachers and friends, with the result that I incurred the punishment, of failure recently in the least trifle, and the reckless waste of half my lifetime. There have been meanwhile, generation after generation, those in the inner chambers, the whole mass of whom could not, on any account, be, through my influence, allowed to fall into extinction, in order that I, unfilial as I have been, may have the means to screen my own shortcomings.

Hence it is that the thatched shed, with bamboo mat windows, the bed of tow and the stove of brick, which are at present my share, are not sufficient to deter me from carrying out the fixed purpose of my mind. And could I, furthermore, confront the morning breeze, the evening moon, the willows by the steps and the flowers in the courtyard, methinks these would moisten to a greater degree my mortal pen with ink; but though I lack culture and erudition, what harm is there, however, in employing fiction and unrecondite language to give utterance to the merits of these characters? And were I also able to induce the inmates of the inner chamber to understand and diffuse them, could I besides break the weariness of even so much as a single moment, or could I open the eyes of my contemporaries, will it not forsooth prove a boon?

This consideration has led to the usage of such names as Chia Yue-ts'un and other similar appellations.

More than any in these pages have been employed such words as dreams and visions; but these dreams constitute the main argument of this work, and combine, furthermore, the design of giving a word of warning to my readers.

Reader, can you suggest whence the story begins?

The narration may border on the limits of incoherency and triviality, but it possesses considerable zest. But to begin.

The Empress Nue Wo, (the goddess of works,) in fashioning blocks of stones, for the repair of the heavens, prepared, at the Ta Huang Hills and Wu Ch'i cave, 36,501 blocks of rough stone, each twelve chang in height, and twenty-four chang square. Of these stones, the Empress Wo only used 36,500; so that one single block remained over and above, without being turned to any account. This was cast down the Ch'ing Keng peak. This stone, strange to say, after having undergone a process of refinement, attained a nature of efficiency, and could, by its innate powers, set itself into motion and was able to expand and to contract.

When it became aware that the whole number of blocks had been made use of to repair the heavens, that it alone had been destitute of the necessary properties and had been unfit to attain selection, it forthwith felt within itself vexation and shame, and day and night, it gave way to anguish and sorrow.

One day, while it lamented its lot, it suddenly caught sight, at a great distance, of a Buddhist bonze and of a Taoist priest coming towards that direction. Their appearance was uncommon, their easy manner remarkable. When they drew near this Ch'ing Keng peak, they sat on the ground to rest, and began to converse. But on noticing the block newly-polished and brilliantly clear, which had moreover contracted in dimensions, and become no larger than the pendant of a fan, they were greatly filled with admiration. The Buddhist priest picked it up, and laid it in the palm of his hand.

"Your appearance," he said laughingly, "may well declare you to be a supernatural object, but as you lack any inherent quality it is necessary to inscribe a few characters on you, so that every one who shall see you may at once recognise you to be a remarkable thing. And subsequently, when you will be taken into a country where honour and affluence will reign, into a family cultured in mind and of official status, in a land where flowers and trees shall flourish with luxuriance, in a town of refinement, renown and glory; when you once will have been there..."

The stone listened with intense delight.

"What characters may I ask," it consequently inquired, "will you inscribe? and what place will I be taken to? pray, pray explain to me in lucid terms." "You mustn't be inquisitive," the bonze replied, with a smile, "in days to come you'll certainly understand everything." Having concluded these words, he forthwith put the stone in his sleeve, and proceeded leisurely on his journey, in company with the Taoist priest. Whither, however, he took the stone, is not divulged. Nor can it be known how many centuries and ages elapsed, before a Taoist priest, K'ung K'ung by name, passed, during his researches after the eternal reason and his quest after immortality, by these Ta Huang Hills, Wu Ch'i cave and Ch'ing Keng Peak. Suddenly perceiving a large block of stone, on the surface of which the traces of characters giving, in a connected form, the various incidents of its fate, could be clearly deciphered, K'ung K'ung examined them from first to last. They, in fact, explained how that this block of worthless stone had originally been devoid of the properties essential for the repairs to the heavens, how it would be transmuted into human form and introduced by Mang Mang the High Lord, and Miao Miao, the Divine, into the world of mortals, and how it would be led over the other bank (across the San Sara). On the surface, the record of the spot where it would fall, the place of its birth, as well as various family trifles and trivial love affairs of young ladies, verses, odes, speeches and enigmas was still complete; but the name of the dynasty and the year of the reign were obliterated, and could not be ascertained.

On the obverse, were also the following enigmatical verses:

Lacking in virtues meet the azure skies to mend, In vain the mortal world full many a year I wend, Of a former and after life these facts that be, Who will for a tradition strange record for me?

K'ung K'ung, the Taoist, having pondered over these lines for a while, became aware that this stone had a history of some kind.

"Brother stone," he forthwith said, addressing the stone, "the concerns of past days recorded on you possess, according to your own account, a considerable amount of interest, and have been for this reason inscribed, with the intent of soliciting generations to hand them down as remarkable occurrences. But in my own opinion, they lack, in the first place, any data by means of which to establish the name of the Emperor and the year of his reign; and, in the second place, these constitute no record of any excellent policy, adopted by any high worthies or high loyal statesmen, in the government of the state, or in the rule of public morals. The contents simply treat of a certain number of maidens, of exceptional character; either of their love affairs or infatuations, or of their small deserts or insignificant talents; and were I to transcribe the whole collection of them, they would, nevertheless, not be estimated as a book of any exceptional worth."

"Sir Priest," the stone replied with assurance, "why are you so excessively dull? The dynasties recorded in the rustic histories, which have been written from age to age, have, I am fain to think, invariably assumed, under false pretences, the mere nomenclature of the Han and T'ang dynasties. They differ from the events inscribed on my block, which do not borrow this customary practice, but, being based on my own experiences and natural feelings, present, on the contrary, a novel and unique character. Besides, in the pages of these rustic histories, either the aspersions upon sovereigns and statesmen, or the strictures upon individuals, their wives, and their daughters, or the deeds of licentiousness and violence are too numerous to be computed. Indeed, there is one more kind of loose literature, the wantonness and pollution in which work most easy havoc upon youth.

"As regards the works, in which the characters of scholars and beauties is delineated their allusions are again repeatedly of Wen Chuen, their theme in every page of Tzu Chien; a thousand volumes present no diversity; and a thousand characters are but a counterpart of each other. What is more, these works, throughout all their pages, cannot help bordering on extreme licence. The authors, however, had no other object in view than to give utterance to a few sentimental odes and elegant ballads of their own, and for this reason they have fictitiously invented the names and surnames of both men and women, and necessarily introduced, in addition, some low characters, who should, like a buffoon in a play, create some excitement in the plot.

"Still more loathsome is a kind of pedantic and profligate literature, perfectly devoid of all natural sentiment, full of self-contradictions; and, in fact, the contrast to those maidens in my work, whom I have, during half my lifetime, seen with my own eyes and heard with my own ears. And though I will not presume to estimate them as superior to the heroes and heroines in the works of former ages, yet the perusal of the motives and issues of their experiences, may likewise afford matter sufficient to banish dulness, and to break the spell of melancholy.

"As regards the several stanzas of doggerel verse, they may too evoke such laughter as to compel the reader to blurt out the rice, and to spurt out the wine.

"In these pages, the scenes depicting the anguish of separation, the bliss of reunion, and the fortunes of prosperity and of adversity are all, in every detail, true to human nature, and I have not taken upon myself to make the slightest addition, or alteration, which might lead to the perversion of the truth.

"My only object has been that men may, after a drinking bout, or after they wake from sleep or when in need of relaxation from the pressure of business, take up this light literature, and not only expunge the traces of antiquated books, and obtain a new kind of distraction, but that they may also lay by a long life as well as energy and strength; for it bears no point of similarity to those works, whose designs are false, whose course is immoral. Now, Sir Priest, what are your views on the subject?"

K'ung K'ung having pondered for a while over the words, to which he had listened intently, re-perused, throughout, this record of the stone; and finding that the general purport consisted of nought else than a treatise on love, and likewise of an accurate transcription of facts, without the least taint of profligacy injurious to the times, he thereupon copied the contents, from beginning to end, to the intent of charging the world to hand them down as a strange story.