yuèdòudá fū nī · dù mù lǐ 'āi Daphne du Maurierzài小说之家dezuòpǐn!!! | |||

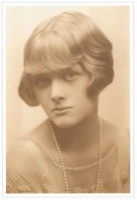

dá fū nī · dù mù lǐ 'āi - shēng píng

dá fū nī · dù mù lǐ 'āi chū shēn shū xiāng mén dì、 yì shù shì jiā, zǔ fù qiáo zhì dù mù lǐ 'āi yě shì xiǎo shuō jiā hé chā tú huà jiā。 zǔ fù de zhè yī jīng lì duì dá fū nī chǎn shēng qiáng liè yǐng xiǎng, shǐ tā zhōng shēng cóng shì wén xué chuàng zuò, bìng yǎng chéng wéi wén xué tè bié shì wéi xiǎo shuō zuò pǐn huà chā tú de xí guàn。 fù qīn jié lā 'ěr dé dù mù lǐ 'āi jué shì shì zhù míng yǎn yuán, bìng cóng shì yǎn chū jīng jì rén de zhí yè, zài zhè yàng de jiā tíng lǐ, dù mù lǐ 'āi zì yòu shòu dào liǎo yì shù de xūn táo。 xì jù duì dá fū nī de yǐng xiǎng yě shì xiǎn 'ér yì jiàn de, tā de xiǎo shuō zhù zhòng qíng jié hé rén wù xìng gé de kè huà, jù yòu yǐn rén rù shèng de xì jù xìng。 dá fū nī dù mù lǐ 'āi kāi shǐ zài lún dūn shòu jiào yù, hòu dào bā lí qiú xué。 tā cōng míng bó xué, jí yòu wén xué tiān fù, 1931 nián tā chuàng zuò chū liǎo tā de dì yī bù cháng piān xiǎo shuō《 kě 'ài de jīng shén》, zài wén tán shàng zhǎn lòutóu jiǎo。 1938 nián chū bǎn liǎo《 lǚ bèi kǎ》 (Rebecca), guó nèi yòu yì wéi《 hú dié mèng》。 zhè bù xiǎo shuō shǐ tā míng zào quán qiú, jī shēn yú shì jiè dāng dài yòu yǐng xiǎng de zuò jiā zhī lín。《 yá mǎi jiā kè zhàn》 shì tā 1935 nián de zuò pǐn, yě shì tā de dài biǎo zuò zhī yī。 tā fā biǎo de yī xì liè gē tè shì làng màn zhù yì zuò pǐn jūn yǐ tā de jiā xiāng kāng wò 'ěr jùn hǎi 'àn wéi bèi jǐng。 tā hái xiě guò yī bù lì shǐ xiǎo shuō hé jǐ gè jù běn。《 yá mǎi jiā kè zhàn》 hé《 hú dié mèng》 fēn bié yú 1939 nián hé 1940 nián bèi bān shàng yín mù。 suī rán《 yá mǎi jiā kè zhàn》 zài yīng guó shàng yǎn shí yǐn qǐ liǎo bù xiǎo de hōng dòng, dàn《 hú dié mèng》 de chéng gōng zé gèng jiā huī huáng。 dù mù lǐ 'āi yú 1969 nián bèi shòu yú yīng dì guó nǚ jué shì xūn wèi。

dá fū nī dù mù lǐ 'āi duì yú zī chǎn jiē jí gōng yè gé mìng dài lái de kē xué jìn bù hé chéng shì wén míng méi yòu xīng qù, dū shì de fú huá hé dào dé lún sàng shǐ tā yàn juàn dū shì shēng huó。 tā lí kāi lún dūn, bì jū yīng guó xī nán bù dà xī yáng yán 'àn de kāng wò 'ěr jùn。 kāng wò 'ěr jùn de nóng chǎng zhuāng yuán yōu xián xiá shì de xiāng xià shēng huó hé qǐ lì mí rén de zì rán fēng guāng hěn shì hé dá fū nī de xīn qíng。 tā qián xīn yán jiū xīn shǎng shí jiǔ shì jì fǎn yìng wéi duō lì yà shí dài fēng sú hé shēng huó de zuò pǐn, yuè dú shí bā shì jì、 shí jiǔ shì jì de gē tè shì xiǎo shuō。 zhè xiē xiǎo shuō chóng shàng yuán shǐ shēng huó de cū yě、 shén mì、 kǒng bù、 mào xiǎn , chōng mǎn làng màn gǎn shāng de qíng diào。 kāng wò 'ěr jùn de shēng huó bǎo liú liǎo hěn duō wéi duō lì yà shí dài de tè zhēng, yě shì xiě zuò gē tè shì xiǎo shuō de zuì hǎo tǔ rǎng。 dá fū nī de zhù yào xiǎo shuō zuò pǐn《 yá mǎi jiā lǚ diàn》、《 hú dié mèng》、《 fǎ lán xī rén de zhī mài》 dōushì yǐ kāng wò 'ěr jùn wéi bèi jǐng de。 yīn cǐ, gē tè shì xiǎo shuō de yì shù fēng gé hé wéi duō lì yà shí dài de mín fēng xiāng sú, shì lǐ jiě、 quán shì dá fū nī kāng wò 'ěr xiǎo shuō de guān jiàn。

dá fū nī · dù mù lǐ 'āi - píng jià

yīng guó zhù míng de xiǎo shuō jiā hé píng lùn jiā fú sī tè (ForsterE.M., 1879 héng 1970) zài píng lùn dá fū nī · dù mù lǐ 'āi de xiǎo shuō shí shuō guò, yīng guó de xiǎo shuō jiā zhōng méi yòu yī gè rén néng gòu zuò dào xiàng dù mù lǐ 'āi zhè yàng dǎ pò tōng sú xiǎo shuō yǔ chún wén xué de jiè xiàn, ràng zì jǐ de zuò pǐn tóng shí mǎn zú zhè liǎng zhǒng wén xué de gòng tóng yào qiú。 fú sī tè bù kuì wéi zhù míng de zuò jiā hé píng lùn jiā, tā duì xiǎo shuō jiā chuàng zuò guò chéng de lǐ jiě hé duì píng lùn jiàn shǎng de zhèng què lǐng wù shǐ tā duì dù mù lǐ 'āi de zuò pǐn bù bào piān jiàn, gěi chū liǎo qià dào hǎo chù de píng lùn。 dá fū nī · dù mù lǐ 'āi suǒ yòng de yì shù biǎo xiàn shǒu fǎ shì zhù zhòng xíng shì hé gù shì qíng jié de tōng sú xiǎo shuō shǒu fǎ, suǒ yǐ bù guǎn shì shénme céng cì de dú zhě, shì zhī shí fènzǐ, hái shì gōng rén、 jiā tíng fù nǚ、 nóng mín, zhǐ yào yòu yī dìng de wén huà, dōukě yǐ dú dá fū nī · dù mù lǐ 'āi de xiǎo shuō, dū huì gǎn dào tōng sú yì dǒng。 zhè yǔ tā xǐ huān gē tè shì de xiǎo shuō shì fēn bù kāi de。 dàn tā de xiǎo shuō yòu yǔ gē tè shì xiǎo shuō yòu hěn dà de qū bié。 gē tè shì xiǎo shuō wèile qíng jié 'ér hū lüè shè huì, hū lüè shēng huó de nèi róng, ér dá fū nī · dù mù lǐ 'āi de xiǎo shuō jù yòu fēi cháng jiān shí de shè huì shēng huó nèi róng, tā shì bǎ rén wù fàng zài tè dìng de shēng huó huán jìng zhōng、 shè huì guān xì zhōng lái kè huà, rén xìng zài jīn qián、 míng lì、 qíng gǎn suǒ zhì chéng de huà miàn zhōng dé dào zhǎn shì hé kǎo yàn。 zhè shì tā rè 'ài hé chóng shàng bù lán wéi lǐ · bó lǎng tè jiě mèi xiǎo shuō de zhí jiē jiēguǒ。 bó lǎng tè jiě mèi de zuò pǐn céng shǐ dá fū nī · dù mù lǐ 'āi shēn shēn gǎn dòng, tā wéi tā men jiě mèi zhuān mén xiě liǎo zhuànjì, yán jiū tā men de zhuànjì guò chéng, zài zì jǐ de xiǎo shuō hé zhuànjì chuàng zuò guò chéng zhōng bù duàn jí qǔ bó lǎng tè jiě mèi de cháng chù, qǔ dé liǎo xiǎn zhù de chéng gōng。 cóng dá fū nī · dù mù lǐ 'āi zuò pǐn zhōng, tōng sú xiǎo shuō jiā yīnggāi kàn dào hé zhòng yě yòu qū guǎ de shēn kè xìng, chún wén xué xiǎo shuō jiā yīnggāi kàn dào qū guǎ wán quán kě yǐ hé zhòng de xiàn shí xìng。

dá fū nī · dù mù lǐ 'āi - zhù yào zuò pǐn

《 hú dié mèng》

《 hú dié mèng》 yuán míng《 lǚ bèi kǎ》, shì dá fū nī · dù mù lǐ 'āi de chéng míng zuò, fā biǎo yú yī jiǔ sān bā nián, yǐ bèi yì chéng 'èr shí duō zhǒng wén zì, zài bǎn chóngyìn sì shí duō cì, bìng bèi gǎi biān bān shàng yín mù, yóu shàn cháng shì yǎn suō shì bǐ yà bǐ xià juésè de míng yǎn yuán láo lún sī · ào lì wéi 'ěr jué shì zhù yǎn nán zhùjué。 gāi piàn shàng yìng yǐ lái jiǔ shèng bù shuāi。

dá fū nī · dù mù lǐ 'āi zài běn shū zhōng chéng gōng dì sù zào liǎo yī gè pō fù shén mì sè cǎi de nǚ xìng lǚ bèi kǎ de xíng xiàng, cǐ rén yú xiǎo shuō kāi shǐ shí jí yǐ sǐ qù, chú zài dàoxù duàn luò zhōng bèi jiànjiē tí dào wài, cóng wèi zài shū zhōng chū xiàn, dàn què shí shí chù chù yīn róng wǎn zài, bìng néng tōng guò qí zhōng pú、 qíng fū děng jì xù kòng zhì màn tuó lì zhuāng yuán zhí zhì zuì hòu jiāng zhè gè zhuāng yuán shāo huǐ。 xiǎo shuō zhōng lìng yī nǚ xìng, jí yǐ gù shì xù shù zhě shēn fèn chū xiàn de dì yī rén chēng,

zhí dé zhù yì de shì, zuò zhě tōng guò kè huà lǚ bèi kǎ nà zhǒng fàng làng xíng hái zhī wài de fǔ huà shēng huó, yǐ jí tā yǔ dé wēn tè de jī xíng hūn yīn, duì yīng guó shàng céng shè huì zhōng de xiǎng lè zhì shàng、 ěr yú wǒ zhà、 qióng shē jí chǐ、 shì lì wěi shàn děng xiàn xiàng zuò liǎo shēng dòng de jiē lù。 zuò zhě hái tōng guò qíng jǐng jiāo róng de shǒu fǎ bǐ jiào chéng gōng dì xuàn rǎn liǎo liǎng zhǒng qì fēn: yī fāng miàn shì chán mián fěi cè de huái xiāng yì jiù, lìng yī fāng miàn shì yīn sēn yā yì de jué wàng kǒng bù。 zhè shuāngchóng qì fēn hù xiāng jiāo dié shèn tòu, jiā zhī quán shū xuán niàn bù duàn, shǐ běn shū chéng wéi yī bù duō nián chàng xiāo bù shuāi de làng màn zhù yì xiǎo shuō。 dàn zài zhè bù zuò pǐn zhōng yě fǎn yìng liǎo zuò zhě mǒu xiē bù zú zhī chù, rú zuò pǐn fǎn yìng de shēng huó miàn bǐ jiào xiá zhǎi, ruò gān miáo xiě jǐng sè de duàn luò yòu diǎn tuō tà, qiě shí yòu zhòng fù děng。

《 yá mǎi jiā kè zhàn》

《 yá mǎi jiā kè zhàn》 shì zuò zhě de lìng yī bù gē tè tǐ xuán yí jīng diǎn xiǎo shuō。 gù shì fā shēng zài yīng guó kāng wò 'ěr jùn de bó dé míng zhǎo zé dì, zài zhè rén yān xī shǎo de zhǎo zé dì zhōng yāng gū líng líng dì chù lì zhe yī zuò liǎng céng gāo de lóu fáng, zhè jiù shì yá mǎi jiā kè zhàn。 èr shí sān suì de nóng jiā nǚ mǎ lì yīn wéi fù mǔ shuāng wáng, wú yǐ wú kào, zhǐ hǎo bèi jǐng lí xiāng, lái dào zhè qióng xiāng pì rǎng tóubèn tā de yí mā pèi xīng sī héng héng yá mǎi jiā kè zhàn de lǎo bǎn niàn。 rán 'ér tā hěn kuài fā xiàn, yá mǎi jiā kè zhàn shí jì shàng shì yī huǒ dǎi tú de mì mì jù diǎn, ér zhè huǒ dǎi tú de shǒu lǐng jiù shì yá mǎi jiā kè zhàn lǎo bǎn、 tā de yí fū qiáo sī · mò lín。 yī kāi shǐ, tā yǐ wéi zhè huǒ dǎi tú zhǐ shì zài 'àn zhōng jìn xíng zǒu sī huó dòng, kě yí mā nà tòng kǔ 'ér kǒng jù de yǎn shén hé yuè hēi fēng gāo shí kè zhàn nèi wài de zhǒng zhǒng qí guài jì xiàng què ràng tā shēn xìn, zǒu sī huó dòng de bèi hòu yī dìng hái yòu gèng wéi kě pà de fàn zuì huó dòng。 wèile jiē kāi zhè gè mí, mǎ lì yòng zì jǐ de róu ruò zhī qū yǔ yī qún shā rén bù zhǎ yǎn de wáng mìng zhī tú zhǎn kāi liǎo yīcháng dǒu zhì dǒu yǒng de jiào liàng。 zài cǐ guò chéng zhōng, tā jié shí liǎo yī gè dào mǎ zéi hé yī gè jiào cháng。 zài yǔ tā men de jiāo wǎng zhōng, mǎ lì de qíng gǎn hé lǐ zhì yòu yī cì xiàn rù liǎo hùn luàn zhī zhōng ……

《 fú shēng mèng》

zhè bù zuò pǐn yǐ kāng wò 'ěr jùn de zhuāng yuán wéi rén wù huó dòng de zhù yào wǔ tái。 zhuāng yuán zhù 'ān bù lǔ sī · ài shí lì yīn bìng chū guó zuò duǎn qī xiū yǎng lǚ xíng, zài yì dà lì xiè hòu shuāng jū de biǎo mèi lā jí 'ào, shuāng shuāng zhuì rù 'ài hé, bìng hěn kuài jié hūn。 xiāo xī chuán dào zhuāng yuán, tì tā guǎn lǐ zhuāng yuán de fěi lì pǔ zì yòu shī qù shuāng qīn, shì táng xiōng 'ān bù lǔ qī jiāng qí fǔ yǎng dà, ān bù lǔ sī shì tā de jiān hù rén、 jiào shī, shì tā de xiōng cháng, yòu xiàng tā de fù qīn, shèn zhì shì tā de zhěng gè shì jiè。 zài shí jì shēng huó zhōng, ān bù lǔ sī yě bǎ fěi lì pǔ shì wéi nóng zhuāng de jì chéng rén, ān bù lǔ sī de sǐ qù duì fěi lì pǔ shì yī gè jù dà de dǎ jī。 suí hòu, lā jí 'ào lái dào zhè gè zhuāng yuán, tā de lái yīn wèi míng, zhī hòu fā shēng yī xì liè de shì bǎ gù shì tuī shàng gāo cháo……

《 zhēng xī dàjiàng jūn》

dá fū nī · dù mù lǐ 'āi yǐ《 hú dié mèng》 xiǎng yù wén tán de yīng guó zuò nǚ zuò jiā dá fū nī · dù mù lǐ 'āi yī shēng zhù zuò shèn fēng,《 zhēng xī dàjiàng jūn》 jiù shì qí zhōng yī bù pō jù dài biǎo xìng de zuò pǐn。

áng nà · hā lǐ sī xiǎo jiě shì lán léi sī tè zhuāng yuán zuì xiǎo de nǚ 'ér, zài shí bā suì shēng rì nà tiān xiè hòu nián qīng jūn guān lǐ chá dé · gé lún wéi 'ěr hòu, jīng lì liǎo yī duàn tián yuán shī bān de làng màn shí guāng。 bù liào, hūn lǐ qián xī, áng nà cù zāo bù xìng, cóng xìng fú de yún duān zhuì rù jué wàng de gǔ dǐ。 ér qià zài cǐ shí, yīng guó nèi zhàn bào fā, áng nà de gè rén shēng mìng bèi wú qíng dì juǎnrù liǎo zhàn zhēng de xuán wō……

《 zhēng xī dàjiàng jūn》 yǐ shí qī shì jì zhōng yè yīng guó nèi zhàn shí qī wéi bèi jǐng, yǐ dāng shí yīng gé lán xī bù fā shēng de bǎo wáng dǎng rén hé yì huì pài zhī jiān de zhēng dǒu jí xiāng hù jiān shì lì xiāozhǎng wéi zhù xiàn, xù shù liǎo yī gè huí cháng dàng qì de 'ài qíng gù shì, dú zhī lìng rén 'ě wàn, cuī rén shēn sī。

《 mǎ lì . ān nī》

běn shū shì dá fū nī · dù mù lǐ 'āi de yī bù zhù yào zuò pǐn。 mǎ lì · ān nī chū shēn dī wēi, dàn tā cóng xiǎo jiù bù gān xīn shòu qióng。 chéng rén hòu, tā yǐ zī sè、 zhì huì、 yě xīn wò xuán yú shè huì。 zài yī xiē bù huái hǎo yì de nán rén de sǒng yǒng xià, tā zǒu shàng liǎo yī tiáo chū rén tóu dì de jié jìng héng héng zuò liǎo yuē kè gōng jué qíng fù。 zài guò liǎo yī duàn fēng guāng de rì zǐ zhī hòu, zāo dào liǎo yí qì。

《 tǒng zhì bā , bù liè diān》

dá fū nī · dù mù lǐ 'āi yī shēng céng shè liè duō zhǒng wén xué tí cái,《 tǒng zhì bā, bù liè diān》 shì tā suǒ zhù de wéi shù bù duō de huàn xiǎng xiǎo shuō zhī yī。

shàonǚ 'āi mǎ yǔ zǔ mǔ mài dé héng héng yī wèi tuì xiū nǚ míng xīng yǐ jí tā suǒ lǐng yǎng de liù gè xìng gé jiǒng yì de nán hái gòng tóng shēng huó zài yīng guó kāng wò 'ěr dì qū, rì zǐ guò dé fù zú 'ér kuài lè。 bù liào, mǒu yī tiān zǎo shàng xǐng lái, zhōu wéi shì jiè tū rán fā shēng liǎo jīng rén de biàn huà: yóu yú yīng guó zhèng fǔ de wú néng, měi guó jūn duì dǎzháo“ gòng jiàn měi yīng guó” de qí hào jìn zhù yīng guó gè gè dì qū, jī qǐ xuān rán dà bō, āi mǎ yī jiā yě bù kě bì miǎn dì bèi juàn jìn liǎo xuán wō。 nì lái shùn shòu? xiāo jí dǐ kàng? hái shì zhù dòng chū jī? āi mǎ yī jiā yǔ bù liè diān wáng guó de suǒ yòu jiā tíng yī yàng, dū xiàn rù liǎo jìn tuì wéi gǔ de xiǎn jìng……

dù mù lǐ 'āi zài xū nǐ de qíng jié bèi jǐng xià, yǐ xián shú de jì qiǎo、 yōu mò de bǐ chù hé dà dǎn de xiǎng xiàng lì jiǎng shù liǎo yī gè yǐn rén rù shèng de gù shì, sù zào liǎo yī zǔ xìng gé xiān míng de rén wù qún xiàng, tóng shí yě hán xù dì shū fā liǎo tā shēn chén de mín zú qíng gǎn, jì bǐng chéng liǎo zuò zhě yī guàn zhòng shì zuò pǐn kě dú xìng de yōu shì, yòu yǐ pō là、 qí tè de wén fēng wéi quán shū zhù rù liǎo pō wéi xīn yíng de yuán sù。

shū míng yǐn zì yīng guó zhù míng shī rén zhān mǔ sī · tānɡ pǔ sēn( 1700-1748) de shī jù, yuán yì shì sòng yáng dà bù liè diān“ jūn lín tiān xià” de bà quán tǒng zhì, zuò zhě yǐ cǐ wéi tí, sì hán fǎn fěng zhī yì。

《 fǎ guó rén de xiǎo wān》

dá fū nī · dù mù lǐ 'āi duǒ nà wéi táo bì dà dū shì shēng huó lái dào hǎi bīn nà wéi lóng bié shù, tā yù dào bìng 'ài shàng liǎo hǎi dào shǒu lǐng, dāng guì zú men jiāng hǎi dào tóu rù jiān yù, duǒ nà zài yī gè qī hēi de yè wǎn yì rán chōng jìn hēi 'àn, qù zhěng jiù tā suǒ 'ài de rén。

dù mù lǐ 'āi shòu shén mì zhù yì yǐng xiǎng hěn shēn。 zuò pǐn dà duō qū zhé, yǐn rén rù shèng, rén wù xiān míng, kè huà xì nì。

fǎ guó rén de xiǎo wān wén cí jīng měi, hé hú dié mèng yī yàng, céng bèi yī xiē guó jiā zuò wéi xué xí yīng yǔ de fàn běn。

《 tì zuì yáng》(《 TheScapegoat》)

dá fū nī · dù mù lǐ 'āi《 tì zuì yáng》 xiě yú 1957 nián。 gù shì fā shēng zài fǎ guó de lā mèng sī chéng。 yī gè jiào fǎ guó lì shǐ de yīng guó jiào shī yuē hàn, duì yú zì jǐ zài kè táng shàng sǐ bǎn dì jiǎng jiě kè wén nèi róng gǎn dào bù mǎn yì, tā rèn wéi tā de gōng zuò shì shī bài de, shēng huó yě shì fá wèi、 bù xìng fú de。 wèile liǎo jiě fǎ guó shè huì de zhēn shí qíng kuàng, zài jiǎ qī lǐ tā lái dào liǎo fǎ guó de lā mèng sī chéng。 zài nà lǐ, tā yù dào yī gè yǔ tā cháng dé yī mó yī yàng de fǎ guó rén ràng · dù gē。 suī rán ràng · dù gē hěn fù yù, dàn yóu yú jiā tíng shēng huó suǒ shì de fán nǎo hé jīng huò de bō lí chǎng bīn yú pò chǎn, tā yě gǎn dào shēng huó hěn kōng xū、 fá wèi, yīn 'ér xiǎng táo lí xiàn shí shēng huó。 liǎng rén xiāng yù hòu, ràng · dù gē zài jiǔ zhōng càn rù liǎo 'ān mián yào, bǎ yuē hàn kāi dé mí mí hú hú de, rán hòu gěi tā huàn shàng liǎo zì jǐ de yī fú, bǎ tā liú zài lǚ guǎn zhōng, ér tā zì jǐ què liù zǒu liǎo。 jiù zhè yàng, yuē hàn bèi ràng · dù gē de jiā rén wù rèn wèishì ràng · dù gē běn rén 'ér jiē huí jiā zhōng。 zài yǔ dù gē yī jiā shēng huó de yī gè xīng qī zhōng, yuē hàn jiàn jiàn shú xī liǎo dù gē jiā de qíng kuàng, bìng duì tā jiā měi gè rén de shēng huó hé gōng zuò zuò liǎo shìdàng de 'ān pái, tā yòu shè fǎ shǐ dù gē de bō lí chǎng bì miǎn dǎo bì, chóngxīn zhèn xīng qǐ lái。 zhè yàng dù gē yī jiā rén yǔ ràng · dù gē de máo dùn yě xiāo chú liǎo。

Personal life

Daphne du Maurier was born in London, the second of three daughters of the prominent actor-manager Sir Gerald du Maurier and actress Muriel Beaumont (maternal niece of William Comyns Beaumont). Her grandfather was the author and Punch cartoonist George du Maurier, who created the character of Svengali in the novel Trilby. These connections helped her in establishing her literary career. du Maurier published some of her very early work in Beaumont's Bystander magazine, and her first novel, The Loving Spirit, was published in 1931. Du Maurier was also the cousin of the Llewelyn Davies boys, who served as J.M. Barrie's inspiration for the characters in the play Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up. As a young child she was introduced to many of the brightest stars of the theatre thanks to the celebrity of her father. On meeting Tallulah Bankhead she was quoted as saying that the actress was the most beautiful creature she had ever seen.[citation needed]

She married Lieutenant-General Sir Frederick "Boy" Browning,with whom she had two daughters and a son (Tessa, Flavia, and Christian). Biographers have noted that the marriage was at times somewhat chilly and that du Maurier could be aloof and distant to her children, especially the girls, when immersed in her writing. "Boy" died in 1965 and soon after Daphne moved to Kilmarth, near Par, which became the setting for The House on the Strand.

Du Maurier has often been painted as a frostily private recluse who rarely mixed in society or gave interviews. An exception to this came after the release of the film A Bridge Too Far, in which her late husband was portrayed in a less-than-flattering light. Du Maurier, incensed, wrote to the national newspapers decrying what she considered unforgivable treatment. Once out of the glare of the public spotlight, however, many remembered her as a warm and immensely funny person who was a welcoming hostess to guests at Menabilly, the house she leased for many years (from the Rashleigh family) in Cornwall. Letters from Menabilly contains the letters from du Maurier to Malet over 30 years, with Malet's commentary. (Malet's real name is Auriel Malet Vaughan.)

Daphne du Maurier was a member of the Cornish nationalist pressure group/political party Mebyon Kernow. She was spoofed by her slightly older fellow writer P. G. Wodehouse as "Daphne Dolores Morehead".

Du Maurier died at age 81 at her home in Cornwall, the region that had been the setting for many of her books. Her body was cremated and her ashes scattered at Kilmarth.

Secret sexual relationships

After her death in 1989, numerous references were made to her secret bisexuality; an affair with Gertrude Lawrence, as well as her attraction for Ellen Doubleday, the wife of her American publisher, were cited. Du Maurier stated in her memoirs that her father, noted manager Gerald du Maurier, had wanted a son and being a tomboy, she had naturally wished to have been born a boy. Her father, unusual for such a prominent theatre personality, was vociferously homophobic. There is some evidence to suggest that Daphne's relationship with her father may have bordered on incest.

In correspondence released by her family for the first time to her biographer, Margaret Forster, du Maurier explained to a trusted few her own unique slant on her sexuality: her personality, she explained, comprised two distinct people—the loving wife and mother (the side she showed to the world) and the lover (a decidedly male energy) hidden to virtually everyone and the power behind her artistic creativity. According to the biography, du Maurier believed the male energy was the demon that fueled her creative life as a writer. Forster maintains that it became evident in personal letters revealed after her death, however, that du Maurier's denial of her bisexuality unveiled a homophobic fear of her true nature.

Titles and honours

* Miss Daphne du Maurier (1907–1932)

* Mrs Frederick Browning; Daphne du Maurier (1932–1946)

* Lady Browning; Daphne du Maurier (1946–1969)

* Lady Browning; Dame Daphne du Maurier DBE (1969–1989)

In the Queen's Birthday Honours List for June 1969, Daphne du Maurier was created a Dame of the British Empire. She never used the title and according to her biographer Margaret Forster, she told no one about the honour. Even her children learned of it from the newspapers. "She thought of pleading illness for the investiture, until her children insisted it would be a great day for the older grandchildren. So she went through with it, though she slipped out quietly afterwards to avoid the attention of the press".

Cultural references

English Heritage created controversy in June 2008 when an application to commemorate her home in Hampstead by a Blue Plaque was rejected by them.

Daphne du Maurier was one of five "Women of Achievement" selected for a set of British stamps issued in August 1996. The others were Dorothy Hodgkin (scientist), Margot Fonteyn (ballerina / choreographer), Elizabeth Frink (sculptor) and Marea Hartman (sports administrator).

Novels, short stories and biographies

Literary critics have sometimes berated du Maurier's works for not being "intellectually heavyweight" like those of George Eliot or Iris Murdoch.[citation needed] By the 1950s, when the socially and politically critical "angry young men" were in vogue, her writing was felt by some to belong to a bygone age of fiction. [citation needed] Today she has been reappraised as a first-rate storyteller, a mistress of suspense: her ability to recreate a sense of place is much admired, and her work remains popular worldwide. For several decades she was the number one author for library book borrowings.[citation needed]

The novel Rebecca, which has been adapted for stage and screen on several occasions, is generally regarded as her masterpiece. One of her strongest influences here was Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë. Her fascination with the Brontë family is also apparent in The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë, her biography of the troubled elder brother to the Brontë girls. The fact that their mother had been Cornish no doubt added to her interest.[citation needed]

Other notable works include The Scapegoat, The House on the Strand, and The King's General. The latter is set in the middle of the first and second English Civil Wars. Though written from the Royalist perspective of her native Cornwall, it gives a fairly neutral view of this period of history.

In addition to Rebecca, several of her other novels have been adapted for the screen, including Jamaica Inn, Frenchman's Creek, Hungry Hill and My Cousin Rachel (1951). The Hitchcock film The Birds (1963) is based on a treatment of one of her short stories, as is the film Don't Look Now (1973). Of the films, du Maurier often complained that the only ones she liked were Alfred Hitchcock's Rebecca and Nicolas Roeg's Don't Look Now. Hitchcock's treatment of Jamaica Inn involved a complete re-write of the ending in order to accommodate the ego of its star, Charles Laughton. Du Maurier also felt that Olivia de Havilland was totally wrong as the (anti-)heroine in My Cousin Rachel. Frenchman's Creek fared rather better with its lavish Technicolor sets and costumes, though du Maurier later regretted her choice of Alec Guinness as the lead in the film of The Scapegoat which she partly financed.

Du Maurier was often categorised as a "romantic novelist" (a term she deplored), though most of her novels, with the notable exception of Frenchman's Creek, are quite different from the stereotypical format of a Georgette Heyer or Barbara Cartland novel. Du Maurier's novels rarely have a happy ending, and her brand of romanticism is often at odds with the sinister overtones and shadows of the paranormal she so favoured. In this light, she has more in common with the "sensation novels" of Wilkie Collins et al., which she admired.

Du Maurier's novel Mary Anne (1954) is a fictionalised account of the real-life story of her great-great-grandmother, Mary Anne Clarke née Thompson (1776–1852). Mary Anne Clarke from 1803 to 1808 was mistress of Frederick Augustus, the Duke of York and Albany (1763–1827). He was the "Grand Old Duke of York" of the nursery rhyme, a son of King George III and brother of the later King George IV. In Ken Follett's thriller The Key to Rebecca, du Maurier's novel Rebecca is used as the key for a code used by a German spy in World War II Cairo. Neville Chamberlain is reputed to have read Rebecca on the plane journey which led to Adolf Hitler signing the Munich Agreement. The central character of her last novel, Rule Britannia, is an aging and eccentric actress who was based on Gertrude Lawrence and Gladys Cooper (to whom it is dedicated). However, the character is most recognisably du Maurier herself.[citation needed]

Indeed, it was in her short stories that she was able to give free rein to the harrowing and terrifying side of her imagination; "The Birds", Don't Look Now, The Apple Tree and The Blue Lenses are exquisitely crafted tales of terror which shocked and surprised her audience in equal measure. Perhaps more than at any other time, du Maurier was anxious as to how her bold new writing style would be received, not just with her readers (and to some extent her critics, though by then she had grown wearily accustomed to their often luke-warm reviews) but her immediate circle of family and friends.

In later life she wrote non-fiction, including several biographies which were well-received. This no doubt came from a deep-rooted desire to be accepted as a serious writer, comparing herself to her close literary neighbour, A. L. Rowse, the celebrated historian and essayist, who lived a few miles away from her house near Fowey.

Also of interest are the "family" novels/biographies which du Maurier wrote of her own ancestry, of which Gerald, the biography of her father, was most lauded. Later she wrote The Glass-Blowers, which traces her French ancestry and gives a vivid depiction of the French Revolution. The du Mauriers is a sequel of sorts, describing the somewhat problematic ways in which the family moved from France to England in the 19th century and finally Mary Anne, a novel based on the life of a notable, and infamous, English ancestor—her great-grandmother Mary Anne Clarke, former mistress of Frederick, Duke of York.

Her final novels reveal just how far her writing style had developed; The House on the Strand (1969) combines elements of "mental time-travel", a tragic love-affair in 14th century Cornwall, and the dangers of using mind-altering drugs. Her final novel, Rule Britannia, written post-Vietnam, plays with the resentment of English people in general and Cornish people in particular at the increasing dominance of the US.

In late 2006 a previously unknown work titled And His Letters Grew Colder was discovered. This was estimated to have been written in the late 1920s, and takes the form of a series of letters tracing an adulterous passionate affair from initial ardour to deflated acrimony.

Plays

Daphne du Maurier wrote three plays. Her first was a successful adaptation of her novel Rebecca, which opened at the Queen's Theatre in London on 5 March 1940 in a production by George Devine, starring Celia Johnson and Owen Nares as the De Winters, and Margaret Rutherford as Mrs. Danvers. At the end of May, following a run of 181 performances, the production transferred to the Strand Theatre, with Jill Furse taking over as Mrs. De Winter and Mary Merrall as Danvers, with a further run of 176 performances.

In the summer of 1943 she began writing the autobiographically-inspired drama The Years Between about the unexpected return of a senior officer, thought killed in action, who finds that his wife has taken over his role as Member of Parliament as well as starting a romantic relationship with a local farmer. It was first staged at the Manchester Opera House in 1944, then transferred to London, opening at Wyndham's Theatre on 10 January 1945 starring Nora Swinburne and Clive Brook. The production, directed by Irene Hentschel became a long-running hit, completing 617 performances.

After 60 years of neglect the play was revived by Caroline Smith at the Orange Tree Theatre in Richmond upon Thames on 5 September 2007, starring Karen Ascoe and Mark Tandy.

Better known is her third play, September Tide, about a middle-aged woman whose bohemian artist son-in-law falls for her. The central character of Stella was originally based on Ellen Doubleday and was merely what Ellen might have been in an English setting and in a different set of circumstances. Again directed by Irene Hentschel, it opened at the Aldwych Theatre on 15 December 1948 with Gertrude Lawrence as Stella, enjoying a run of 267 performances before closing at the beginning of August 1949. It was to lead to a close personal and social relationship between Daphne and Gertrude.

Since then September Tide has received occasional revivals, most recently at the Comedy Theatre in London in January 1994, starring film and stage actress Susannah York in the role originally created by Lawrence, with Michael Praed as the saturnine young artist. Reviewing the production for the Richmond & Twickenham Times, critic John Thaxter wrote: "The play and performances delicately explore their developing relationship. And as the September gales batter the Cornish coast, isolating Stella's cottage from the outside world, she surrenders herself to the truth of a moment of unconventional tenderness."

Plagiarism allegations

Shortly after Rebecca was published in Brazil, critic Álvaro Lins and other readers pointed out many resemblances between du Maurier's book and the work of Brazilian writer Carolina Nabuco. Nabuco's A sucessora (The Successor) has a main plot similar to Rebecca, including a young woman marrying a widower and the strange presence of the first wife — plot features also shared with the far older Jane Eyre. Nina Auerbach alleged, in her book Daphne du Maurier, Haunted Heiress, that du Maurier read the Brazilian book when the first drafts were sent to be published in England and based her famous bestseller on it. According to Nabuco's autobiography, she refused to sign a contract brought to her by a United Artists' worker in which she agreed that the similarities between her book and the movie were mere coincidence. Du Maurier denied copying Nabuco's book, as did her publisher, claiming that the plot used in Rebecca was quite common.

Publications

Fiction

* The Loving Spirit (1931)

* I'll Never Be Young Again (1932)

* The Progress of Julius (1933) (later re-published as Julius)

* Jamaica Inn (1936)

* Rebecca (1938)

* Rebecca (1940) (play—du Maurier's own stage adaptation of her novel)

* Happy Christmas (1940) (short story)

* Come Wind, Come Weather (1940) (short story collection)

* Frenchman's Creek (1941)

* Hungry Hill (1943)

* The Years Between (1945) (play)

* The King's General (1946)

* September Tide (1948) (play)

* The Parasites (1949)

* My Cousin Rachel (1951)

* The Apple Tree (1952) (short story collection, AKA Kiss Me Again, Stranger)

* Mary Anne (1954)

* The Scapegoat (1957)

* Early Stories (1959) (short story collection, stories written between 1927–1930)

* The Breaking Point (1959) (short story collection, AKA The Blue Lenses)

* Castle Dor (1961) (with Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch)

* The Birds and Other Stories (1963) (republication of The Apple Tree)

* The Glass-Blowers (1963)

* The Flight of the Falcon (1965)

* The House on the Strand (1969)

* Not After Midnight (1971) (short story collection, AKA Don't Look Now)

* Rule Britannia (1972)

* "The Rendezvous and Other Stories" (1980) (short story collection)

Non-fiction

* Gerald (1934)

* The du Mauriers (1937)

* The Young George du Maurier (1951)

* The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë (1960)

* Vanishing Cornwall (includes photographs by her son Christian)(1967)

* Golden Lads (1975)

* The Winding Stairs (1976)

* Growing Pains -— the Shaping of a Writer (1977) (a.k.a. Myself When Young -— the Shaping of a Writer)

* Enchanted Cornwall (1989)

Translations

* Hungry Hill (1943) was translated into Dutch and published under the title 'De kopermijn. De geschiedenis van de familie Brodrick' (literally: The coppermine. The history of the family Brodrick).